Transnistria, the "General Plan East", and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miriam Weiner Archival Collection

THE MIRIAM WEINER ARCHIVAL COLLECTION BABI YAR (in Kiev), Ukraine September 29-30, 1941 From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kiev-and-babi-yar "On September 29-30, 1941, SS and German police units and their auxiliaries, under guidance of members of Einsatzgruppe C, murdered a large portion of the Jewish population of Kiev at Babi Yar, a ravine northwest of the city. As the victims moved into the ravine, Einsatzgruppen detachments from Sonderkommando 4a under SS- Standartenführer Paul Blobel shot them in small groups. According to reports by the Einsatzgruppe to headquarters, 33,771 Jews were massacred in this two-day period. This was one of the largest mass killings at an individual location during World War II. It was surpassed only by the massacre of 50,000 Jews at Odessa by German and Romanian units in October 1941 and by the two-day shooting operation Operation Harvest Festival in early November 1943, which claimed 42,000-43,000 Jewish victims." From Wikipedia.org https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babi_Yar According to the testimony of a truck driver named Hofer, victims were ordered to undress and were beaten if they resisted: "I watched what happened when the Jews—men, women and children—arrived. The Ukrainians[b] led them past a number of different places where one after the other they had to give up their luggage, then their coats, shoes and over- garments and also underwear. They also had to leave their valuables in a designated place. There was a special pile for each article of clothing. -

Analele Universităţii Din Craiova, Seria Istorie, Anul XIX, Nr. 2(26)/2014

Analele Universităţii din Craiova, Seria Istorie, Anul XIX, Nr. 2(26)/2014 CONTENTS STUDIES AND ARTICLES Anișoara Băbălău, THE FISCAL ORGANISATION OF WALLACHIA IN BRANCOVAN ERA .................................................................................................................................. 5 Elena Steluţa Dinu, HEALTH LAWS IN THE PERIOD 1874-1910 .............................. 15 Adi Schwarz, THE STRUGGLE OF THE JEWS FOR THEIR POLITICAL RIGHTS IN THE VIEW OF WESTERN JOURNALISTS (1876-1914) ............................................. 23 Cosmin-Ştefan Dogaru, LE PORTRAIT DE CHARLES DE HOHENZOLLERN- SIGMARINGEN. UN REPERE DANS L’HISTOIRE DE L’ETAT ROUMAIN ............. 31 Stoica Lascu, THE SITUATION OF THE BALKAN ROMANIANS REFLECTED IN “REVISTA MACEDONIEI” MAGAZINE (BUCHAREST; 1905-1906) ...................... 43 Gheorghe Onişoru, MAY 15, 1943: DISSOLUTION OF THE KOMINTERN AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF ROMANIA .......................................... 75 Cezar Stanciu, CHALLENGES TO PROLETARIAN INTERNATIONALISM: THE COMMUNIST PARTIES’ CONFERENCE IN MOSCOW, 1969 .................................. 85 Lucian Dindirică, ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL ORGANIZATION OF ROMANIA UNDER THE LEADERSHIP OF NICOLAE CEAUŞESCU ........................................... 101 Virginie Wanyaka Bonguen Oyongmen, ARMÉE CAMEROUNAISE ET DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONOMIQUE ET SOCIAL DE LA NATION: LE CAS DU GÉNIE MILITAIRE (1962-2012) ................................................................................ 109 Nicolae Melinescu, THE MARITIME -

The Holocaust in Ukraine

This memorial was dedicated in 1994 in Kiev, Ukraine, in memory of the more than 33,000 Jews who were killed at Babi Yar. Excerpted from Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova and published on this website with permission from the publisher, Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc. | A sea of faces at the dedication of the memorial at Babi Yar, a ravine in Kiev where Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C carried out | the mass slaughter of more than 33,000 Jews from Kiev and surrounding towns on September 29–30, 1941. The killings at Babi Yar ` continued in subsequent months (victims included Jews, Communists and POWs), for an estimated total of 100,000 people. 330 Excerpted from Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova and published on this website with permission from the publisher, Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc. 803 Excerpted from Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova and published on this website with permission from the publisher, Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc. 331 810 8 Kamen Kashirskiy, Ukraine, 1994 Holocaust memorial erected in 1992 in the center of town at the former ghetto site on Kovel Street where “3,000 citizens of Jewish nationality were driven and who became the victims of the German Fascist aggressors. Eternal Memory to them!” 8 811 Kamen Kashirskiy, Ukraine, 1994 Holocaust memorial erected in 1960 on the site of the Jewish cemetery “where German Fascist aggressors and their accomplices shot 2,600 citizens of Jewish nationality. To their eternal memory.” 812 8 Kamen Kashirskiy, Ukraine, 1994 Holocaust memorial erected in 1991 in memory of the “100 citizens of Jewish nationality who were shot by German Fascist aggressors at this place” 336 Excerpted from Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova and published on this website with permission from the publisher, Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc. -

Lista Cercetătorilor Acreditaţi

Cereri aprobate de Colegiul C.N.S.A.S. Cercetători acreditaţi în perioada 31 ianuarie 2002 – 23 februarie 2021 Nr. crt. Nume şi prenume cercetător Temele de cercetare 1. ABOOD Sherin-Alexandra Aspecte privind viața literară în perioada comunistă 2. ABRAHAM Florin Colectivizarea agriculturii în România (1949-1962) Emigraţia română şi anticomunismul Mecanisme represive sub regimul comunist din România (1944-1989) Mişcări de dreapta şi extremă dreaptă în România (1927-1989) Rezistenţa armată anticomunistă din România după anul 1945 Statutul intelectualului sub regimul comunist din România, 1944-1989 3. ÁBRAHÁM Izabella 1956 în Ardeal. Ecoul Revoluţiei Maghiare în România 4. ABRUDAN Gheorghe-Adrian Intelectualitatea şi rezistenţa anticomunistă: disidenţă, clandestinitate şi anticomunism postrevoluţionar. Studiu de caz: România (1977-2007) 5. ACHIM Victor-Pavel Manuscrisele scriitorilor confiscate de Securitate 6. ACHIM Viorel Minoritatea rromă din România (1940-1989) Sabin Manuilă – activitatea ştiinţifică şi politică 7. ADAM Dumitru-Ionel Ieroschimonahul Nil Dorobanţu, un făclier al monahismului românesc în perioada secolului XX 8. ADAM Georgeta Presa română în perioada comunistă; scriitorii în perioada comunistă, deconspirare colaboratori 9. ADAMEŞTEANU Gabriela Problema „Eterul”. Europa Liberă în atenţia Securităţii Scriitorii, ziariştii şi Securitatea Viaţa şi opera scriitorului Marius Robescu 10. ADĂMOAE Emil-Radu Monografia familiei Adămoae, familie acuzată de apartenență la Mișcarea Legionară, parte a lotului de la Iași Colaborarea cu sistemul opresiv 11. AELENEI Paul Istoria comunei Cosmești, jud. Galați: oameni, date, locuri, fapte 12. AFILIE Vasile Activitatea Mişcării Legionare în clandestinitate 13. AFRAPT Nicolae Presiune şi represiune politică la liceul din Sebeş – unele aspecte şi cazuri (1945-1989) 14. AFUMELEA Ioan Memorial al durerii în comuna Izvoarele, jud. -

Sept. 19, 2019 Attorney General Phil Weiser to Address Hatred and Extremism at Holocaust Remembrance Ceremony

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Melanie Avner, [email protected], 720-670-8036 Attorney General Phil Weiser to Address Hatred and Extremism at Holocaust Remembrance Ceremony Sept. 22 Denver, CO (Sept. 19, 2019) – Attorney General Phil Weiser will give a special address on confronting hate and extremism at the Mizel Museum’s annual Babi Yar Remembrance Ceremony on Sunday, September 22 at 10:00 a.m. at Babi Yar Memorial Park (10451 E. Yale Ave., Denver). The event commemorates the Babi Yar Massacre and honors all victims and survivors of the Holocaust. “The rise in anti-Semitism and other vicious acts of hatred in the U.S. and around the world underscore the need to confront racism and bigotry in our communities,” said Weiser. “We must honor and remember the victims of the Holocaust, learning from the lessons of the past in order to combat intolerance and hate in the world today.” Weiser’s grandparents and mother survived the Holocaust; his mother is one of the youngest living survivors. She was born in the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, and she and her mother were liberated the next day by the Second Infantry Division of the U.S. Army. Nearly 34,000 Jews were executed at the Babi Yar ravine on the outskirts of Kiev in Nazi-occupied Ukraine on September 29-30, 1941. This was one of the largest mass murders at an individual location during World War II. Between 1941 and 1943, thousands more Jews, Roma, Communists and Soviet prisoners of war also were killed there. It is estimated that some 100,000 people were murdered at Babi Yar during the war. -

Duiliu Marcu - Semicentenar 1966-2016

1 DUILIU MARCU - SEMICENTENAR 1966-2016 2016 - ANUL „DUILIU MARCU” 2 „Preocuparea mea de a găsi soluţii originale româneşti, de a lua din arhitectura clasică numai claritatea, simplitatea, ponderea, euritmia, propor iile, meticulozitatea studiilor de detaliu, precizia execu iei [...] au constituit pentru mine o linie de conduită,ț un crez care mi-a servit ca îndreptar în întreaga meaț activitate. Iată în ce împrejurări am încercat să creez.” (Duiliu Marcu, Duiliu Marcu – Arhitectură, 1912-1960, Ed. Tehnică, 1960, Bucure ti, p. 21) ș 3 Ştampila Duiliu Marcu în 1915. Arhivele Naţionale ale României - „Donaţia Duiliu Marcu” 4 1. PREZENTARE ARHITECT 1.1. BIOGRAFIE Duiliu Marcu este cel care dovede te o polivalen ă ie ită din comun în arhitectura românească, fiind personalitatea acesteia care se confundă practic cu aproape întreaga evolu ie a arhitecturii noastre. În acest sens, activitatea sa profesionalăș se desfăț oarăș pe parcursul a peste 50 de ani (1912- 1966), timp în care la conducerea României democratice se schimbă patru regi (Carolț I (1866-1914), Ferdinand I (1914-1927), Mihai I (1927-1930 i 1940-1947) i Carolș al II-lea (1930-1940)) i, ulterior, se instaurează regimul comunist. Mai mult decât atât, destinul arhitectului este legat de familia regală i mai ales de personalitatea lui Carol al II-lea. ș ș ș Născut la Calafat (25 martie 1885), Marcu provine dintr-o familie modestă. Mamaș sa era fără ocupa ie, iar tatăl său căpitan în armata regală. Studiază la coala primară din Fălticeni, iar clasa întâia de liceu la Dorohoi. În anul 1900 se înscrie la sec ia reală a Liceul Carol I din Craiova - inaugurat cu numai cinci ani înainte,ț chiar în prezen a suveranului, pentru a continua studiile.ș Aici se remarcă prin note foarte bune la desen, ob inute în fiecare an de studiu, în bazaț cărora i se conferă numeroase premii. -

Istoria Primului Control Administrativ Al Populaţiei României Întregite Din 24 Aprilie – 5 Mai 1927

NICOLAE ENCIU* „Confidenţial şi exclusiv pentru uzul autorităţilor administrative”. ISTORIA PRIMULUI CONTROL ADMINISTRATIV AL POPULAŢIEI ROMÂNIEI ÎNTREGITE DIN 24 APRILIE – 5 MAI 1927 Abstract The present study deals with an unprecedented chapter of the demographic history of in- terwar Romania – the first administrative control of the population from 24 April to 5 May 1927. Done in the second rule of General Alexandru Averescu, the administrative control had the great merit of succeeding to determine, for the first time after the Great Union of 1918, the total number of the population of the Entire Romania, as well as the demographic dowry of the historical provinces that constituted the Romanian national unitary state. Keywords: administrative control, census, counting, total population, immigration, emigration, majority, minority, ethnic structure. 1 e-a lungul timpului, viaţa şi activitatea militarului de carieră Alexandru DAverescu (n. 9.III.1859, satul Babele, lângă Ismail, Principatele Unite, astăzi în Ucraina – †3.X.1938, Bucureşti, România), care şi-a legat numele de ma- rea epopee naţională a luptelor de la Mărăşeşti, în care s-a ilustrat Armata a 2-a, comandată de el, membru de onoare al Academiei Române (ales la 7 iunie 1923), devenit ulterior mareşal al României (14 iunie 1930), autor a 12 opere despre ches- tiuni militare, politice şi de partid, inclusiv al unui volum de memorii de pe prima linie a frontului1, a făcut obiectul mai multor studii, broşuri şi lucrări ale specialiş- tilor, pe durata întregii perioade interbelice2. * Nicolae Enciu – doctor habilitat în istorie, conferenţiar universitar, director adjunct pentru probleme de ştiinţă, Institutul de Istorie, mun. -

Collaboration and Resistance—The Ninth Fort As a Test Case

Aya Ben-Naftali Director, Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust Collaboration and Resistance: The Ninth Fort as a Test Case The Ninth Fort is one of a chain of nine forts surrounding the city of Kovno, Lithuania. In connection with the Holocaust, this location, like Ponary, Babi Yar, and Rumbula, marks the first stage of the Final Solution—the annihilation of the Jewish people. The history of this site of mass slaughtering is an extreme case of the Lithuanians’ deep involvement in the systematic extermination of the Jews, as well as an extraordinary case of resistance by prisoners there. 1. Designation of the Ninth Fort as a Major Killing Site The forts surrounding Kovno were constructed between 1887 and 1910 to protect the city from German invasion. The Ninth Fort, six kilometers northwest of the city, was considered the most important of them. In the independent Republic of Lithuania, it served as an annex of the central prison of Kovno and had a capacity of 250 prisoners. Adjacent to the fort was a state-owned farm of eighty-one hectares, where the prisoners were forced to work the fields and dig peat.1 The Ninth Fort was chosen as the main regional execution site in advance. Its proximity to the suburb of Vilijampole (Slobodka), where the Kovno ghetto had been established, was apparently the main reason. In his final report on the extermination of Lithuanian Jews, Karl Jäger, commander of Einsatzkommando 3 and the Security Police and SD in Lithuania, noted the factors that informed his choice of killing sites (Exekutionsplatze): …The carrying out of such Aktionen is first of all an organizational problem. -

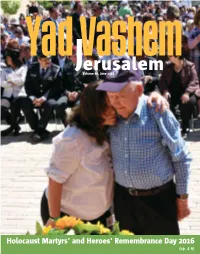

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Poland Study Guide Poland Study Guide

Poland Study Guide POLAND STUDY GUIDE POLAND STUDY GUIDE Table of Contents Why Poland? In 1939, following a nonaggression agreement between the Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was again divided. That September, Why Poland Germany attacked Poland and conquered the western and central parts of Poland while the Page 3 Soviets took over the east. Part of Poland was directly annexed and governed as if it were Germany (that area would later include the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz- Birkenau). The remaining Polish territory, the “General Government,” was overseen by Hans Frank, and included many areas with large Jewish populations. For Nazi leadership, Map of Territories Annexed by Third Reich the occupation was an extension of the Nazi racial war and Poland was to be colonized. Page 4 Polish citizens were resettled, and Poles who the Nazis deemed to be a threat were arrested and shot. Polish priests and professors were shot. According to historian Richard Evans, “If the Poles were second-class citizens in the General Government, then the Jews scarcely Map of Concentration Camps in Poland qualified as human beings at all in the eyes of the German occupiers.” Jews were subject to humiliation and brutal violence as their property was destroyed or Page 5 looted. They were concentrated in ghettos or sent to work as slave laborers. But the large- scale systematic murder of Jews did not start until June 1941, when the Germans broke 2 the nonaggression pact with the Soviets, invaded the Soviet-held part of Poland, and sent 3 Chronology of the Holocaust special mobile units (the Einsatzgruppen) behind the fighting units to kill the Jews in nearby forests or pits. -

Wendy Lower, Ph.D

Wendy Lower, Ph.D. Acting Director, Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2016- ) Director, Mgrublian Center for Human Rights John K. Roth Professor of History George R. Roberts Fellow Claremont McKenna College 850 Columbia Ave Claremont, CA 91711 [email protected] (909) 607 4688 Research Fields • Holocaust Studies • Comparative Genocide Studies • Human Rights • Modern Germany, Modern Ukraine • Women’s History Brief Biography • 2016-2018, Acting Director, Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. USA • 2014- 2017, Director, Mgrublian Center for Human Rights, Claremont McKenna College • 2012-present, Professor of History, Claremont McKenna College • 2011-2012, Associate Professor, Affiliated Faculty, Department of History, Strassler Family Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Clark University, Worcester, Mass, USA • 2010-2012 Project Director (Germany), German Witnesses to War and its Aftermath, Oral History Department, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. USA • 2010-2012, Visiting Professor, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy • 2007-2012 Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, LMU • 2004-2009 Assistant Professor (tenure track), Department of History, Towson University USA (on leave, research fellowship 2007-2009) • 2000-2004, Director, Visiting Scholars Program, Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. • 1999-2000 Assistant Professor, Adjunct Faculty, Center for German and Contemporary European Studies, Georgetown University, USA 1 • 1999-2000 Assistant Professor, Adjunct Faculty, Department of History, American University, USA • 1999 Ph.D., European History, American University, Washington D.C. • 1996-1998 Project Coordinator, Oral History Collection of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), Center for the Study of Intelligence, and Georgetown University • 1994 Harvard University, Ukrainian Research Institute, Ukrainian Studies Program • 1993 M.A. -

INTRODUCTION Friederike Eigler

INTRODUCTION Moving Forward: New Perspectives on German-Polish Relations in Contemporary Europe Friederike Eigler German, Georgetown University Since the end of the Cold War and the reconfiguration of the map of Europe, scholars across the disciplines have looked anew at the geopolitical and geocultural dimensions of East Central Europe. Although geographi- cally at the periphery of Eastern Europe, Germany and its changing dis- courses on the East have also become a subject of this reassessment in recent years. Within this larger context, this special issue explores the fraught history of German-Polish border regions with a special focus on contemporary literature and film.1 The contributions examine the represen- tation of border regions in recent Polish and German literature (Irene Sywenky, Claudia Winkler), filmic accounts of historical German and Polish legacies within contemporary European contexts (Randall Halle, Meghan O’Dea), and the role of collective memory in contemporary German-Polish relations (Karl Cordell). Bringing together scholars of Polish and German literature and film, as well as political science, some of the contributions also ponder the advantages of regional and transnational approaches to issues that used to be discussed primarily within national parameters. The German-Polish relationship has undergone dramatic changes over the past century. The shifting borders between between Germany (earlier Prussia) and Poland over the past 200-plus years are the most visible sign of what, until recently, was a highly fraught relationship. To review some of the most important cartographic shifts: • The multiple partitions of Poland between Russia, the Habsburg Monarchy, and Prussia in the late eighteenth century resulted in the disappearance of the Polish state for 120 years.