Fame Labour and Microcelebrity Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the Youtuber Zoella

In The Time of the Microcelebrity Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella Jerslev, Anne Published in: International Journal of Communication Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-ND Citation for published version (APA): Jerslev, A. (2016). In The Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5078/1822 Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 5233–5251 1932–8036/20160005 In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella ANNE JERSLEV University of Copenhagen, Denmark This article discusses the temporal changes in celebrity culture occasioned by the dissemination of digital media, social network sites, and video-sharing platforms, arguing that, in contemporary celebrity culture, different temporalities are connected to the performance of celebrity in different media: a temporality of plenty, of permanent updating related to digital media celebrity; and a temporality of scarcity distinctive of large-scale international film and television celebrities. The article takes issue with the term celebrification and suggests that celebrification on social media platforms works along a temporality of permanent updating, of immediacy and authenticity. Taking UK YouTube vlogger and microcelebrity Zoella as the analytical case, the article points out that microcelebrity strategies are especially connected with the display of accessibility, presence, and intimacy online; moreover, the broadening of processes of celebrification beyond YouTube may put pressure on microcelebrities’ claim to authenticity. Keywords: celebrification, microcelebrity, YouTubers, vlogging, social media, celebrity culture YouTubers are a huge phenomenon online. -

Political Realities As Portrayed by Internet Personalities, Creative Truth Or Social Control? Charles L. Mitchell Grambling Stat

Political Realities as Portrayed by Internet Personalities, Creative Truth or Social Control? Charles L. Mitchell Grambling State University Prepared for delivery at the 2020 Western Political Science Association Los Angeles, April 9, 2020, and the Western Political Science Association, Virtual Meeting, May 21, 2020 1 Abstract Political Realities as Portrayed by Internet Personalities, Creative Truth or Social Control? The trends happening in Internet and their influence on politics is the research problem this paper attempts to resolve. Internet’s beginnings as an idea that would improve the transaction strength of networks is reasoned. Recent developments in Internet that decrease the importance of interpersonal transactions and that increase the prominence of Internet personalities are presented. Questions about how influencers influence network’s ability to assist transactions are reviewed. The transaction as a unit of both economic and psychological analysis is discussed. Psychologists are presented to think of transactions as between three ego states—parent, child, and adult. The possibility that Internet personalities upset interpersonal transaction realities on the same ego level is imagined. How political influence could be created by encouraging more transactions from one ego state to another, for example from parent to child, is mentioned. Beliefs that transactions across different ego states is tension producing is hypothesized to effect political persuasion. Analysis of Internet personalities attempts to answer if they are likely to change Internet in the direction of more creative truth or if they will affect social control. Differences between people who think Internet is intended to make economic reasoning prevail in transactions and those who like orchestrated politics are presented. -

Mothers in Science

The aim of this book is to illustrate, graphically, that it is perfectly possible to combine a successful and fulfilling career in research science with motherhood, and that there are no rules about how to do this. On each page you will find a timeline showing on one side, the career path of a research group leader in academic science, and on the other side, important events in her family life. Each contributor has also provided a brief text about their research and about how they have combined their career and family commitments. This project was funded by a Rosalind Franklin Award from the Royal Society 1 Foreword It is well known that women are under-represented in careers in These rules are part of a much wider mythology among scientists of science. In academia, considerable attention has been focused on the both genders at the PhD and post-doctoral stages in their careers. paucity of women at lecturer level, and the even more lamentable The myths bubble up from the combination of two aspects of the state of affairs at more senior levels. The academic career path has academic science environment. First, a quick look at the numbers a long apprenticeship. Typically there is an undergraduate degree, immediately shows that there are far fewer lectureship positions followed by a PhD, then some post-doctoral research contracts and than qualified candidates to fill them. Second, the mentors of early research fellowships, and then finally a more stable lectureship or career researchers are academic scientists who have successfully permanent research leader position, with promotion on up the made the transition to lectureships and beyond. -

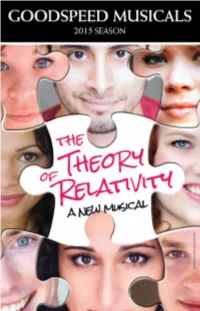

The Theory of Relativity

Theory of Relativity | 11 Cast | 12 Songs and Scenes | 12 Who’s Who | 13 Authors’ Notes | 19 About Goodspeed Musicals | 25 History of The Norma Terris Theatre | 27 The Goodspeed Opera House Foundation | 29 Corporate Support | 30 Foundation & Government Support | 30 Looking to the Future | 31 Goodspeed Musicals Staff | 34 For Your Information | 44 Audio and video recording and photography are prohibited in the theatre. Please turn off your cell phone, beeper, watch alarm or anything else that might make a distracting noise during the GMS2 performance. Unwrap any candies, cough drops, or mints before the performance begins to avoid disturbing your fellow audience members or the actors on stage. We appreciate your cooperation. Editor Lori A. Cartwright ADVERTISING OnStage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with OnStage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Kettering, OH 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. JBI Publishing is a division of OnStage Publications, Inc. Contents © 2015. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. 2 GOODSPEED MUSICALS | 2015 SEASON Theory of Relativity | 11 Cast | 12 Songs and Scenes | 12 Who’s Who | 13 Authors’ Notes | 19 About Goodspeed Musicals | 25 History of The Norma Terris Theatre | 27 The Goodspeed Opera House Foundation | 29 Corporate Support | 30 Foundation & Government Support | 30 Looking to the Future | 31 Goodspeed Musicals Staff | 34 For Your Information | 44 Audio and video recording and photography are prohibited in the theatre. Please turn off your cell phone, beeper, watch alarm or anything else that might make a distracting noise during the GMS2 performance. -

Entry List Information Provided by Student Online Registration and Does Not Reflect Last Minute Changes

Entry List Entry List Information Provided by Student Online Registration and Does Not Reflect Last Minute Changes Junior Paper Round 1 Building: Hornbake Room: 0108 Time Entry # Affiliate Title Students Teacher School 10:00 am 10001 IA The Partition of India: Conflict or Compromise? Adam Pandian Cindy Bauer Indianola Middle School 10:15 am 10002 AK Mass Panic: The Postwar Comic Book Crisis Claire Wilkerson Adam Johnson Romig Middle School 10:30 am 10003 DC Functions of Reconstructive Justice: A Case of Meyer Leff Amy Trenkle Deal MS Apartheid and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa 10:45 am 10004 NE The Nuremberg Trials to End a Conflict William Funke Roxann Penfield Lourdes Central Catholic School 11:00 am 10005 SC Edwards V. South Carolina: A Case of Conflict and Roshni Nandwani Tamara Pendleton Forestbrook Middle Compromise 11:15 am 10006 VT The Green Mountain Parkway: Conflict and Katie Kelley Susan Guilmette St. Paul's Catholic School Compromise over the Future of Vermont 11:30 am 10007 NH The Battle of Midway: The Turning Point in the Zachary Egan Chris Soule Paul Elementary School Pacific Theatre 11:45 am 10008 HI Gideon v. Wainwright: The Unfulfilled Promise of Amy Denis Kacey Martin Aiea Intermediate School Indigent Defendants' Rights 12:00 pm 10009 PA The Christmas Truce of 1914: Peace Brought by Drew Cohen Marian Gibfried St. Peter's School Soldiers, Not Governments 12:15 pm 10010 MN The Wilderness Act of 1964 Grace Philippon Catie Jacobs Twin Cities German Immersion School Paper Junior Paper Round 1 Building: Hornbake Room: 0125 Time Entry # Affiliate Title Students Teacher School 10:00 am 10011 AS Bloody Mary: A Catholic Who Refused To Liualevaiosina Chloe-Mari Tiana Trepanier Manumalo Academy - Compromise Leiato Elementary 10:15 am 10012 MS The Conflicts and Compromises of Lucy Maud Corgan Elliott Carolyn Spiller Central School Montgomery 10:30 am 10013 MN A Great Compromise: The Sherman Plan Saves the Lucy Phelan Phil Hohl Cyber Village Academy Constitutional Convention of 1787 10:45 am 10014 MI Gerald R. -

How Chinese Internet Celebrity Influences Consumer Attitude to Purchase on E-Commerce

How Chinese Internet Celebrity Influences consumer attitude to purchase on E-commerce In the case of internet fashion celebrity Dayi Zhang Master’s Thesis 15 credits Department of Business Studies Uppsala University Spring Semester of 2019 Date of Submission: 2019-06-05 Ying Li Qian Cai Supervisor: Pao Kao Abstract Problem/Purpose: Internet celebrities have shown huge commercial value by operating their E-commerce in the Chinese market. This article aims to research How Chinese internet celebrity influences consumers’ attitude to purchase on E-commerce. Method: The Primary data is collected by semi-structured interviews with consumers who followed the internet celebrity and bought products from her online stores. Meanwhile, word frequency analysis of posted context and comments on the internet is proceeded to conduct secondary data to support findings. Findings: Our findings show that the traditional source attractiveness, expertise, and involvement of celebrity are important to impact on the consumers’ attitude and drive to purchase behavior. However, source trustworthiness is not essential, and the perceived trustworthiness is limited in specialized fields (e.g. fashion) and is hard extend to other areas (e.g. cosmetics). Furthermore, perceived authenticity will reinforce trustworthiness and intimacy, and perceived interconnectedness will result in frequent and regular buying habit. Implementation: This research can serve to internet celebrities who are running or intend to start their E-commerce in China. Moreover, it is hoped this study of internet celebrity E- commerce in China can serve for future comparative studies of internet celebrity globally. Keywords: Internet celebrity, Source credibility, Consumer attitude, Purchase intention Table of contents 1. -

1 Detta Rahmawan Selebtwits Micro Celebrity Practitioners in Indonesian Twittersphere.Indd

SELEBTWITS: MICRO-CELEBRITY PRACTITIONERS IN INDONESIAN TWITTERSPHERE 1 SELEBTWITS: MICRO-CELEBRITY PRACTITIONERS IN INDONESIAN TWITTERSPHERE Detta Rahmawan Newcastle University, UK ABSTRACT Drawn from the notion that Twitter is a suitable context for micro-celebrity practices (Marwick, 2010) this research examines interactions between Indonesian Twitter-celebrities called selebtwits and their followers. The results suggest that several strategies include: stimulated conversation, audience recognition, and vari- ous level of self-disclosure that have been conducted by the selebtwits to maintain the relationship with their followers. This research also found that from the follower viewpoint, interaction with selebtwits is often per- ceived as an “endorsement” and “achievement”. However, there are others who are not particularly fond of the idea of the selebtwits-follower’s engagement. Some selebtwits-followers’ interactions lead to “digital in- timacy”, while others resemble parasocial interaction and one-way communication. Furthermore, this study suggests that in the broader context, selebtwits are perceived in both positive and negative ways. Keywords: Twitter, social media, micro-celebrity, selebtwits SELEBTWIT: MICRO-CELEBRITY DALAM RUANG TWITTER DI INDONESIA ABSTRAK Twitter adalah salah satu media sosial di mana wacana mengenai micro-celebrity berkembang (Marwick, 2010). Berangkat dari hal tersebut, penelitian ini bertujuan untuk melihat wacana micro-celebrity di Indo- nesia dengan menganalisis interaksi yang terjadi diantara selebritis Twitter Indonesia yang disebut selebtwit dengan para followers (pengikut) nya. Penelitian ini menemukan bahwa terdapat beberapa strategi komuni- kasi yang dilakukan oleh para selebtwit untuk menjaga hubungan dengan para followers-nya, antara lain: percakapan yang terstimulasi, pengakuan terhadap followers sebagai khalayak, dan berbagai strategi pen- gungkapan diri. Hasil lain menunjukkan bahwa dari sudut pandang para followers, interaksi mereka dengan para selebtwit sering dipandang sebagai sarana untuk promosi diri. -

Ecommerce in China – the Future Is Already Here How Retailers and Brands Are Innovating to Succeed in the Most Dynamic Retail Market in the World

Total Retail 2017 eCommerce in China – the future is already here How retailers and brands are innovating to succeed in the most dynamic retail market in the world www.pwchk.com Retail 2017 survey highlights mobile commerce, What is the greatest challenge you face in secure platforms, and big data analytics, among providing an omni-channel experience for others, as key investment areas for global your customer? retailers to thrive in years to come. Budget 30% constraints This report “eCommerce in China – the future Michael Cheng Too many legacy Asia Pacific & is already here” builds on the survey findings of 21% systems to change Hong Kong/China the global Total Retail 2017 to identify nine key trends that are shaping the recovery and growth Difficult to integrate Retail and Consumer % 20 existing systems Leader in the retail and consumer products sector in China. In order to stay ahead of the competition, Not a priority for our % retailers need to consider investing in identifying 13 leadership team customer needs, finding the right partners Lack of and investing beyond O2O into omni-channel % 10 expertise Foreword fulfilment. The report particularly highlights how eCommerce is evolving from being purely Lack of internal China, the largest eCommerce market in the transactional to now shaping innovation and % 6 resources world, is now setting the benchmark for present customer engagement trends across China’s and future global retailing. This is driven by its retail and consumer products sector. Source: PwC & SAP Retailer Survey; Base: 312 mobile-first consumer behaviour, innovative social commerce model, and a trusted digital China is a must-play, must-win market for China’s retail market has never been so payments infrastructure. -

Social Media's Star Power: the New Celebrities and Influencers

Social Media’s Star Power: The New Celebrities and Influencers Stuart A. Kallen San Diego,3 CA ® © 2021 ReferencePoint Press, Inc. Printed in the United States For more information, contact: ReferencePoint Press, Inc. PO Box 27779 San Diego, CA 92198 www.ReferencePointPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING- IN- PUBLICATION DATA Names: Kallen, Stuart A., 1955- author. Title: Social media’s star power : the new celebrities and influencers / by Stuart A. Kallen. Description: San Diego, CA : ReferencePoint Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020012340 (print) | LCCN 2020012341 (ebook) | ISBN 9781682829318 (library binding) | ISBN 9781682829325 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Social media--Juvenile literature. | Internet personalities--Juvenile literature. | Social influence--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC HM742 .K35 2021 (print) | LCC HM742 (ebook) | DDC 302.23/1--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012340 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012341 Contents Introduction 6 The New Entertainment Chapter One 10 Billions of Hits, Millions of Dollars Chapter Two 24 Mainstream Social Media Superstars Chapter Three 38 Reality Check Chapter Four 52 Profi ting from Bad Advice Source Notes 66 For Further Research 70 Index 73 Picture Credits 79 About the Author 80 5 Chapter One Billions of Hits, Millions of Dollars After her photos were posted to Reddit in 2012, she became an instant internet celebrity. -

Proquest Dissertations

Library and Archives Bibliotheque et l+M Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54229-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54229-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

Internet Celebrity Economy”

Journal of Frontiers in Educational Research DOI: 10.23977/jfer.2021.010324 Clausius Scientific Press, Canada Volume 1, Number 3, 2021 Analysis of Internet Marketing from the Perspective of “Internet Celebrity Economy” Yu Lejie Shandong Vocational College of Science and Technology, Weifang City, Shandong Province, 261053, China Keywords: Internet celebrity economy, Internet marketing, Analysis, Strategy Abstract: Analysing network marketing from the perspective of “network economy” requires grasping the constituent elements of “Internet celebrity economy”. Starting from the existence of the economic system, it should first establish an orderly relationship between supply and demand. Based on the analysis of online marketing, the article puts forward an online marketing strategy from the perspective of “Internet celebrity economy”, namely, rational selection of online marketing entities, provision of manufacturer information to facilitate promotion, and use of well-known platforms for marketing. 1. Introduction It is generally believed that the “Internet celebrity economy” is represented by young and beautiful fashionistas, led by the taste and vision of celebrities, for selection and visual promotion, gathering popularity on social media, and relying on a huge fan group for orientation marketing, a process of turning fans into purchasing power. Analysing network marketing from the perspective of “network economy” requires grasping the constituent elements of “Internet celebrity economy”. Starting from the existence of the economic system, it should first establish an orderly supply- demand relationship. From the inherent requirements of marketing activities, it can be seen that this supply-demand relationship is established on the basis of satisfying consumer needs and preferences, rather than the type of supply-driven sales model. -

Gurdon Institute 2006 PROSPECTUS / ANNUAL REPORT 2005

The Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute 2006 PROSPECTUS / ANNUAL REPORT 2005 Gurdon I N S T I T U T E PROSPECTUS 2006 ANNUAL REPORT 2005 http://www.gurdon.cam.ac.uk THE GURDON INSTITUTE 1 CONTENTS THE INSTITUTE IN 2005 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION........................................................3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND..............................................................4 CENTRAL SUPPORT SERVICES...........................................................5 FUNDING...........................................................................................................5 RESEARCH GROUPS........................................................................6 MEMBERS OF THE INSTITUTE..............................................42 CATEGORIES OF APPOINTMENT..................................................42 POSTGRADUATE OPPORTUNITIES.............................................42 SENIOR GROUP LEADERS..................................................................42 GROUP LEADERS......................................................................................48 SUPPORT STAFF..........................................................................................53 INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS....................................................55 OTHER INFORMATION STAFF AFFILIATIONS................................................................................62 HONOURS AND AWARDS................................................................63 EDITORIAL BOARDS OF JOURNALS...........................................63