Waimea Inlet Restoration Information for Communities on Best Practice Approaches CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moutere Gravels

LAND USE ON THE MOUTERE GRAVELS, I\TELSON, AND THE DilPORTANOE OF PHYSIC.AL AND EOONMIC FACTORS IN DEVJt~LOPHTG THE F'T:?ESE:NT PATTERN. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS ( Honours ) GEOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF NEW ZEALAND 1953 H. B. BOURNE-WEBB.- - TABLE OF CONTENTS. CRAFTER 1. INTRODUCTION. Page i. Terminology. Location. Maps. General Description. CH.AFTER 11. HISTORY OF LAND USE. Page 1. Natural Vegetation 1840. Land use in 1860. Land use in 1905. Land use in 1915. Land use in 1930. CHA.PrER 111. PRESENT DAY LAND USE. Page 17. Intensively farmed areas. Forestry in the region. Reversion in the region. CHA.PrER l V. A NOTE ON TEE GEOLOGY OF THE REGION Page 48. Geological History. Composition of the gravels. Structure and surface forms. Slope. Effect on land use. CHA.mm v. CLIMATE OF THE REGION. Page 55. Effect on land use. CRAFTER Vl. SOILS ON Tlffi: MGm'ERE GRAVELS. Page 59. Soil.tYJDes. Effect on land use. CHAPrER Vll. ECONOMIC FACTORS WrIICH HAVE INFLUENCED TEE LAND USE PATTERN. Page 66. ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS. ~- After page. l. Location. ii. 2. Natu.ral Vegetation. i2. 3. Land use in 1905. 6. Land use regions and generalized land use. 5. Terraces and sub-regions at Motupiko. 27a. 6. Slope Map. Folder at back. 7. Rainfall Distribution. 55. 8. Soils. 59. PLATES. Page. 1. Lower Moutere 20. 2. Tapawera. 29. 3. View of Orcharding Arf;;a. 34a. 4. Contoured Orchard. 37. 5. Reversion and Orchards. 38a. 6. Golden Downs State Forest. 39a. 7. Japanese Larch. 40a. B. -

Notes on Japanese Ferns II. by T. Nakai

Notes on Japanese Ferns II. By T. Nakai (I.) PolypodiaceaeR. BROWN, Prodr. F1. Nov. Holland. p. I45 (i8io), pro parte. Plzysematiurn KAULFVSS in Flora (1829) p. 34I. The species of this genus have not articulation at the stipes of fronds. The indusium is complete sac, bursting irregularly in its maturity. DIEi.S took this for Woodsia on account of the lack of articulation at the stipes of Woodsia polystichoides. The ordinary Woodsiahas horizontal articulation in the middle of the stipes of the frond. But in Woodsiapolystichoides articulation comes at the upper end of the stipes. It is oblique and along the segmental line many lanceolate paleae arrange in a peculiar mode. DIETShas overlooked this fact, and perhaps CHRISTENSENhad the same view. By this peculiar mode of articulation Woodsiapolystichoides evidently repre- sents a distinct section Acrolysis NAKAI,sect. nov. However, the indusium of Woodsiapolystichoides is Woodsia-type; incomplete mem- brane covering the lower part of sorus and ending with hairs. This mode of indusium is fundamentally different from I'hysennatium,and I take Woodsia distinct from Plzysematzum. Among the numbers of species of Japanese Woodsia only one belongs to Pliysenzatium. P/zysernatiulnmanclzuricnse NAKAI, comb. nov. Woodsiamanclzuriensis W. J. HOOKER,2nd Cent. t. 98 (i86i). Diacalpe manclzuriensisTREVISAN Nuo. Giorn. Bot. Ital. VII. p. I6o (I875). Hab. Japonia, Corea, Manchuria et China bor. Vittaria formosana NAKAI,sp. nov. (Eu-Vittaria). Vittaria elongata (non SWARTZ)HARRINGTON in Journ. Linn. Soc. XVI. p. 3 3 (1878); pro parte, quoad plantam ex Formosa. BAKER July,1925 NAKAI-NOTESON JAPANESE FERNS II 177 in BRITTEN,Journ. Bot. -

Feasibility of Restoring Tasman Bay Mussel Beds

Feasibility of restoring Tasman Bay mussel beds Prepared for Nelson City Council May 2012 29 June 2012 11.52 a.m. Authors/Contributors : Sean Handley Stephen Brown For any information regarding this report please contact: Sean Handley Marine Ecologist Nelson Marine Ecology and Aquaculture +64-3-548 1715 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd 217 Akersten Street, Port Nelson PO Box 893 Nelson 7040 New Zealand Phone +64-3-548 1715 Fax +64-3-548 1716 NIWA Client Report No: NEL2012-013 Report date: May 2012 NIWA Project: ELF12243 © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. 29 June 2012 11.52 a.m. Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ -

Identification Guide Freshwater Pests of NZ

Freshwater pests of New Zealand Invasion of our freshwaters by alien species is a major issue. Today, few if any New Zealand water bodies support a biota that is wholly native. Over 200 freshwater plant and animal species have been introduced to New Zealand, many of which have naturalised and become pests, or have the potential to become pests. Impacts from these species are significant, including reduction in indigenous biodiversity, destabilisation of aquatic habitats, economic losses through lost power generation, impeded drainage or irrigation, and reduced opportunity for recreational activities like boating and fishing. The Ministry for the Environment publication Alien Invaders (Champion et al. 2002) outlines the entry pathways, methods of spread, and impacts and management of freshwater pests, and is recommended for anyone interested in this field. This freshwater pest identification guide is divided into three sections: fish, invertebrates, and plants. It provides keys to the identity of pest fish (7 species) and aquatic weeds (38 species) and provides photographs and information on the known distribution, identification features, similar species and how to distinguish them, dispersal mechanisms, and biosecurity risks for these and an additional 12 introduced invertebrates. The technical terms used in the keys are explained in a glossary at the back of the guide. If you find a pest species in a different locality to those listed in the guide, please forward this information to P. Champion, NIWA, P O Box 11115, Hamilton. Page 5 Page 23 Page 37 Page 84 Field key for identifying the main exotic fish in New Zealand freshwater (Italics indicate fish that key out as native species. -

Nitrate Sources and Residence Times of Groundwater in the Waimea Plains, Nelson

Journal of Hydrology (NZ) 50 (2): 313-338 2011 © New Zealand Hydrological Society (2011) Nitrate sources and residence times of groundwater in the Waimea Plains, Nelson Michael K. Stewart1, Glenn Stevens2, Joseph T. Thomas2, Rob van der Raaij3, Vanessa Trompetter3 1 Aquifer Dynamics & GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand. Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Tasman District Council, Private Bag 4, Richmond, New Zealand 3 GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Abstract the various wells. The timing of the derived Nitrate concentrations exceeding Ministry of nitrate input history shows that both the Health potable limits (11.3 mg/L nitrate-N) diffuse sources and the point source were have been a problem for Waimea Plains present from the 1940s, which is anecdotally groundwater for a number of years. This work the time from which there were increased uses nitrogen isotopes to identify the input nitrate sources on the plains. The large sources of the nitrate. The results in relation piggery was closed in the mid-1980s. to nitrate contours have revealed two kinds Unfortunately, major sources of nitrate of nitrate contamination in Waimea Plains (including the piggery) were located on groundwater – diffuse contamination in the the main groundwater recharge zone of the eastern plains area (in the vicinity and south plains in the past, leading to contamination of Hope) attributed to the combined effects of the Upper and Lower Confined Aquifers. of the use of inorganic fertilisers and manures The contamination travelled gradually for market gardening and other land uses, northwards, affecting wells on the scale of and point source contamination attributed to decades. -

Molecular Identification of Azolla Invasions in Africa: the Azolla Specialist, Stenopelmus Rufinasus Proves to Be an Excellent Taxonomist

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303097315 Molecular identification of Azolla invasions in Africa: The Azolla specialist, Stenopelmus rufinasus proves to be an excellent taxonomist Article in South African Journal of Botany · July 2016 DOI: 10.1016/j.sajb.2016.03.007 READS 51 6 authors, including: Paul T. Madeira Martin P. Hill United States Department of Agriculture Rhodes University 24 PUBLICATIONS 270 CITATIONS 142 PUBLICATIONS 1,445 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Julie Angela Coetzee I.D. Paterson Rhodes University Rhodes University 54 PUBLICATIONS 423 CITATIONS 15 PUBLICATIONS 141 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: I.D. Paterson letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 16 August 2016 South African Journal of Botany 105 (2016) 299–305 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Molecular identification of Azolla invasions in Africa: The Azolla specialist, Stenopelmus rufinasus proves to be an excellent taxonomist P.T. Madeira a,M.P.Hillb,⁎,F.A.DrayJr. a,J.A.Coetzeeb,I.D.Patersonb,P.W.Tippinga a United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service, Invasive Plant Research Laboratory, 3225 College Avenue, Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33314, United States b Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Biological control of Azolla filiculoides in South Africa with the Azolla specialist Stenopelmus rufinasus has been Received 18 September 2015 highly successful. However, field surveys showed that the agent utilized another Azolla species, thought to be Received in revised form 18 February 2016 the native Azolla pinnata subsp. -

0172 Wine Nelson Guide 2016 FINAL Copy

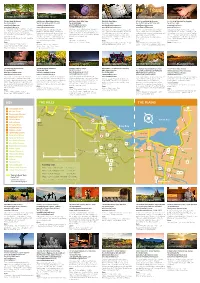

1. FOSSIL RIDGE WINES 2. MILCREST ESTATE 3. GREENHOUGH VINEYARD 4. BRIGHTWATER VINEYARDS 5. KAIMIRA WINES 6. SEIFRIED ESTATE 72 Hart Road, Richmond 114 Haycock Road, Hope, Nelson 411 Paton Road, RD1, Hope 546 Main Road, Hope 97 Livingston Road, Brightwater Cnr. SH 60 & Redwood Rd, Appleby Tel: 03 544 9463 Tel: 03 544 9850 or 027 554 6622 Tel: 03 542 3868 Tel: 03 544 1066 Tel: 03 5423 491 or 021 2484 107 Tel: 03 544 1600 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.fossilridge.co.nz www.milcrestestate.co.nz www.greenhough.co.nz www.brightwaterwine.co.nz www.KaimiraWines.com www.seifried.co.nz An intensively managed boutque vineyard Milcrest Estate is a boutque vineyard Welcome to our cellar door just fve minutes “You will feel at home at the spacious cellar Certfed organic vineyards and winery. A treasure amongst the vines. The perfect in the Richmond foothills. Established 1998, situated at the foothills of the Richmond from Richmond. Winemakers in Hope for door. There is an unpretentous, helpful and Visit our cellar door/local art gallery for way to spend an afernoon – relaxing in the currently featuring seven wine optons. Ranges producing award winning Aromatcs, twenty fve years. Taste our certfed organic enjoyable approach to wine tastng here. tastng and sales of your favourite wines plus vineyard garden or next to the open freplace Visitors invited for cellar door tastngs in an Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Syrah, Dolceto Hope Vineyard wines – Chardonnay, Riesling, These seriously made wines show clarity, some more unusual varietes. -

Growth Performance and Biochemical Profile of Azolla Pinnata and Azolla Caroliniana Grown Under Greenhouse Conditions

Arch Biol Sci. 2019;71(3):475-482 https://doi.org/10.2298/ABS190131030K Growth performance and biochemical profile of Azolla pinnata and Azolla caroliniana grown under greenhouse conditions Taylan Kösesakal1,* and Mustafa Yıldız2 1Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey 2Department of Aquaculture, Faculty of Aquatic Sciences, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: January 31, 2019; Revised: March 22, 2019; Accepted: April 25, 2019; Published online: May 10, 2019 Abstract: This study aimed to evaluate the growth performance, pigment content changes, essential amino acids (EAAs), fatty acids (FAs), and proximate composition of Azolla pinnata and Azolla caroliniana grown in a greenhouse. Plants were grown in nitrogen-free Hoagland’s solution at 28±2°C/21±2°C, day/night temperature and 60-70% humidity and examined on the 3rd, 5th, 10th and 15th days. The mean percentage of plant growth and relative growth rate for A. pinnata were 119% and 0.148 gg-1day-1, respectively, while for A. caroliniana these values were 94% and 0.120 gg-1day-1, respectively. Compared to day 3, the amount of total chlorophyll obtained on day 15 decreased significantly (p<0.05) for A. pinnata while the total phenolic and flavonoid contents increased significantly (p<0.05) from the 3rd to the 15th day. However, the total phenolic and flavonoid contents did not differ (p>0.0.5) in A. caroliniana. The crude protein, lipid, cellulose, ash values and the amounts of EAAs were higher in A. pinnata than A. caroliniana. Palmitic acid, oleic acid, and lignoceric acid were found to be predominant in A. -

The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography

ISSN 1031-8062 ISBN 0 7305 5592 5 The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography K. A. Rodgers and Carol' Cant.-11 Technical Reports of the Australian Museu~ Number-t TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Technical Reports of the Australian Museum is D.J.G . Griffin a series of occasional papers which publishes Editor: bibliographies, catalogues, surveys, and data bases in J.K. Lowry the fields of anthropology, geology and zoology. The journal is an adjunct to Records of the Australian Assistant Editor: J.E. Hanley Museum and the Supplement series which publish original research in natural history. It is designed for Associate Editors: the quick dissemination of information at a moderate Anthropology: cost. The information is relevant to Australia, the R.J. Lampert South-west Pacific and the Indian Ocean area. Invertebrates: Submitted manuscripts are reviewed by external W.B. Rudman referees. A reasonable number of copies are distributed to scholarly institutions in Australia and Geology: around the world. F.L. Sutherland Submitted manuscripts should be addressed to the Vertebrates: Editor, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney A.E . Greer South, N.S.W. 2000, Australia. Manuscripts should preferably be on 51;4 inch diskettes in DOS format and ©Copyright Australian Museum, 1988 should include an original and two copies. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the Editor. Technical Reports are not available through subscription. New issues will be announced in the Produced by the Australian Museum Records. Orders should be addressed to the Assistant 15 September 1988 Editor (Community Relations), Australian Museum, $16.00 bought at the Australian Museum P.O. -

Assessing Phylogenetic Relationships in Extant Heterosporous Ferns (Salviniales), with a Focus on Pilularia and Salvinia

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, 157, 673–685. With 2 figures Assessing phylogenetic relationships in extant heterosporous ferns (Salviniales), with a focus on Pilularia and Salvinia NATHALIE S. NAGALINGUM*, MICHAEL D. NOWAK and KATHLEEN M. PRYER Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA Received 4 June 2007; accepted for publication 29 November 2007 Heterosporous ferns (Salviniales) are a group of approximately 70 species that produce two types of spores (megaspores and microspores). Earlier broad-scale phylogenetic studies on the order typically focused on one or, at most, two species per genus. In contrast, our study samples numerous species for each genus, wherever possible, accounting for almost half of the species diversity of the order. Our analyses resolve Marsileaceae, Salviniaceae and all of the component genera as monophyletic. Salviniaceae incorporate Salvinia and Azolla; in Marsileaceae, Marsilea is sister to the clade of Regnellidium and Pilularia – this latter clade is consistently resolved, but not always strongly supported. Our individual species-level investigations for Pilularia and Salvinia, together with previously published studies on Marsilea and Azolla (Regnellidium is monotypic), provide phylogenies within all genera of heterosporous ferns. The Pilularia phylogeny reveals two groups: Group I includes the European taxa P. globulifera and P. minuta; Group II consists of P. americana, P. novae-hollandiae and P. novae-zelandiae from North America, Australia and New Zealand, respectively, and are morphologically difficult to distinguish. Based on their identical molecular sequences and morphology, we regard P. novae-hollandiae and P. novae-zelandiae to be conspecific; the name P. novae-hollandiae has nomenclatural priority. -

A Guide to Freshwater Pest Plants of the Wellington Region REPORT THESE WEEDS – 0800 496 734

A guide to freshwater pest plants of the Wellington region REPORT THESE WEEDS – 0800 496 734 Contact information For more information contact Greater Wellington Regional Council’s Biosecurity team. Phone us: 0800 496 734 Visit our website: www.gw.govt.nz/biosecurity Send us an email: [email protected] The Greater Wellington Regional Council’s Biosecurity Pest plant officers can: • Help you identify pest plants on your property. • Provide advice on different control methods. • Undertake control work in areas outlined in the Regional Pest Management Strategy. Download the Greater Wellington Regional Pest Management Strategy – www.gw.govt.nz/pest-plants-3 Acknowledgements This guide has been jointly funded by the Ministry for Environment Fresh Start for Freshwater Cleanup Fund and the partners in the Wairarapa Moana Wetland project. All photos have been provided by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) unless otherwise stated. Contents Foreword 2 Purpose 3 Understanding aquatic plants 4 Prevent the spread 6 Control options 7 Identifying aquatic weeds 9 Aquatic pest plant identification Canadian pondweed 10 Cape pondweed 12 Curled pondweed 14 Egeria 16 Ferny azolla 18 Hornwort 20 Lagarosiphon 22 Monkey musk 24 Parrot’s feather 26 Swamp lily 28 Water pepper 30 Water plantain 32 Yellow flag iris 34 Report these weeds to us! Alligator weed 37 Californian arrowhead 38 Californian bulrush 39 Delta arrowhead 40 Eelgrass 41 Hawaiian arrowhead 42 Hydrilla 43 Manchurian wild rice 44 Purple loosestrife 45 Salvinia 46 Senegal tea 47 Spartina 48 Water hyacinth 49 1 “The effects of freshwater pest Foreword plants on Maori cultural values” Freshwater pest plants are considered a problem by most people regardless of their cultural beliefs. -

The Hills 60 16 Almost All Family-Owned

Kaiteriteri Nelson is home to 21 cellar doors, The Hills 60 16 almost all family-owned. This Riwaka High St High means that when you visit the cellar door, you’ll often meet the Motueka winemaker and experience their passion first hand. 10. RIMU GROVE WINERY 13. KINA BEACH VINEYARD 16. RIWAKA RIVER ESTATE 19. DUNBAR ESTATES Motueka Valley Highway r ive 60 Motueka R Come enjoy our handcrafted Pinot Noir, Bronte Road East Boutique vineyard in stunning coastal setting, 21 Dee Road, Kina, Tasman Artisan vineyard producing ‘Resurgence’ wines 60 Takaka Hill Highway, Dunbar Estates’ Accommodation, Cellar Door, Café Dunbar Estates 13 14 Kina Peninsula 15 Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Gewürztraminer and (off Coastal Highway), producing single vineyard multiple award Tel: 03 526 6252 – individual, well-crafted wines of unique and Riwaka & Vineyard adjacent to the picturesque Motueka 1469 Motueka Valley Highway 19 Kina Beach Rd Riesling wines overlooking the scenic Waimea Inlet. RD1, Upper Moutere winning wines. or 027 521 5321 distinctive character from limestone soils. Our extra- Tel: 03 528 8819 river. Taste and purchase wines from our Nelson and RD1, Ngatimoti Open: Tel: 03 540 2345 Accommodation: [email protected] virgin olive oil is also available at our cellar door. Mob: 021 277 2553 Central Otago Vineyards. Stay or relax in the beautiful Motueka 7196 The Hills Summer: 11.00am – 5.00pm daily. [email protected] Charming guest cottages set amongst the vines, www.kinabeach.co.nz Delightful vineyard accommodation is now available. [email protected] countryside while enjoying wine, food and Tel: 03 526 8598 Winter: By appointment.