Platonic Solids and the Golden Ratio∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Archimedean Or Semiregular Polyhedra

ON THE ARCHIMEDEAN OR SEMIREGULAR POLYHEDRA Mark B. Villarino Depto. de Matem´atica, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San Jos´e, Costa Rica May 11, 2005 Abstract We prove that there are thirteen Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra by using Euler’s polyhedral formula. Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 RegularPolyhedra .............................. 2 1.2 Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra . ..... 2 2 Proof techniques 3 2.1 Euclid’s proof for regular polyhedra . ..... 3 2.2 Euler’s polyhedral formula for regular polyhedra . ......... 4 2.3 ProofsofArchimedes’theorem. .. 4 3 Three lemmas 5 3.1 Lemma1.................................... 5 3.2 Lemma2.................................... 6 3.3 Lemma3.................................... 7 4 Topological Proof of Archimedes’ theorem 8 arXiv:math/0505488v1 [math.GT] 24 May 2005 4.1 Case1: fivefacesmeetatavertex: r=5. .. 8 4.1.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 8 4.1.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 9 4.2 Case2: fourfacesmeetatavertex: r=4 . .. 10 4.2.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 10 4.2.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 11 4.3 Case3: threefacesmeetatavertes: r=3 . ... 11 4.3.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 11 4.3.2 All faces have at least four sides and one exactly four sides: p1 =4 6 p2 6 p3. 12 4.3.3 All faces have at least five sides and one exactly five sides: p1 =5 6 p2 6 p3 13 1 5 Summary of our results 13 6 Final remarks 14 1 Introduction 1.1 Regular Polyhedra A polyhedron may be intuitively conceived as a “solid figure” bounded by plane faces and straight line edges so arranged that every edge joins exactly two (no more, no less) vertices and is a common side of two faces. -

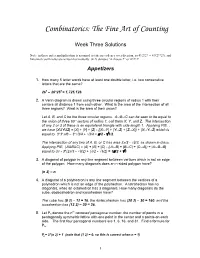

Combinatorics: the Fine Art of Counting

Combinatorics: The Fine Art of Counting Week Three Solutions Note: in these notes multiplication is assumed to take precedence over division, so 4!/2!2! = 4!/(2!*2!), and binomial coefficients are written horizontally: (4 2) denotes “4 choose 2” or 4!/2!2! Appetizers 1. How many 5 letter words have at least one double letter, i.e. two consecutive letters that are the same? 265 – 26*254 = 1,725,126 2. A Venn diagram is drawn using three circular regions of radius 1 with their centers all distance 1 from each other. What is the area of the intersection of all three regions? What is the area of their union? Let A, B, and C be the three circular regions. A∪B∪C can be seen to be equal to the union of three 60° sectors of radius 1, call them X, Y, and Z. The intersection of any 2 or 3 of these is an equilateral triangle with side length 1. Applying PIE, , we have |XUYUZ| = |X| + |Y| + |Z| - (|X∪Y| + |Y∪Z| + |Z∪X|) + |X∪Y∪Z| which is equal to 3*3*π/6 – 3*√3/4 + √3/4 = π/2 - √3/2. The intersection of any two of A, B, or C has area 2π/3 - √3/2, as shown in class. Applying PIE, |AUBUC| = |A| + |B| + |C| - (|A∪B| + |B∪C| + |C∪A|) + |A∪B∪B| equal to 3π - 3*(2π/3 - √3/2) + (π/2 - √3/2) = 3π/2 + √3 3. A diagonal of polygon is any line segment between vertices which is not an edge of the polygon. -

Almost-Magic Stars a Magic Pentagram (5-Pointed Star), We Now Know, Must Have 5 Lines Summing to an Equal Value

MAGIC SQUARE LEXICON: ILLUSTRATED 192 224 97 1 33 65 256 160 96 64 129 225 193 161 32 128 2 98 223 191 8 104 217 185 190 222 99 3 159 255 66 34 153 249 72 40 35 67 254 158 226 130 63 95 232 136 57 89 94 62 131 227 127 31 162 194 121 25 168 200 195 163 30 126 4 100 221 189 9 105 216 184 10 106 215 183 11 107 214 182 188 220 101 5 157 253 68 36 152 248 73 41 151 247 74 42 150 246 75 43 37 69 252 156 228 132 61 93 233 137 56 88 234 138 55 87 235 139 54 86 92 60 133 229 125 29 164 196 120 24 169 201 119 23 170 202 118 22 171 203 197 165 28 124 6 102 219 187 12 108 213 181 13 109 212 180 14 110 211 179 15 111 210 178 16 112 209 177 186 218 103 7 155 251 70 38 149 245 76 44 148 244 77 45 147 243 78 46 146 242 79 47 145 241 80 48 39 71 250 154 230 134 59 91 236 140 53 85 237 141 52 84 238 142 51 83 239 143 50 82 240 144 49 81 90 58 135 231 123 27 166 198 117 21 172 204 116 20 173 205 115 19 174 206 114 18 175 207 113 17 176 208 199 167 26 122 All rows, columns, and 14 main diagonals sum correctly in proportion to length M AGIC SQUAR E LEX ICON : Illustrated 1 1 4 8 512 4 18 11 20 12 1024 16 1 1 24 21 1 9 10 2 128 256 32 2048 7 3 13 23 19 1 1 4096 64 1 64 4096 16 17 25 5 2 14 28 81 1 1 1 14 6 15 8 22 2 32 52 69 2048 256 128 2 57 26 40 36 77 10 1 1 1 65 7 51 16 1024 22 39 62 512 8 473 18 32 6 47 70 44 58 21 48 71 4 59 45 19 74 67 16 3 33 53 1 27 41 55 8 29 49 79 66 15 10 15 37 63 23 27 78 11 34 9 2 61 24 38 14 23 25 12 35 76 8 26 20 50 64 9 22 12 3 13 43 60 31 75 17 7 21 72 5 46 11 16 5 4 42 56 25 24 17 80 13 30 20 18 1 54 68 6 19 H. -

Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell

Article Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell Jihyun Choi and Jae-Hyouk Lee * Department of Mathematics, Ewha Womans University 52, Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03760, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3277-3346 Received: 10 July 2018; Accepted: 26 July 2018; Published: 7 August 2018 Abstract: In this article, we have an explicit description of the binary isosahedral group as a 600-cell. We introduce a method to construct binary polyhedral groups as a subset of quaternions H via spin map of SO(3). In addition, we show that the binary icosahedral group in H is the set of vertices of a 600-cell by applying the Coxeter–Dynkin diagram of H4. Keywords: binary polyhedral group; icosahedron; dodecahedron; 600-cell MSC: 52B10, 52B11, 52B15 1. Introduction The classification of finite subgroups in SLn(C) derives attention from various research areas in mathematics. Especially when n = 2, it is related to McKay correspondence and ADE singularity theory [1]. The list of finite subgroups of SL2(C) consists of cyclic groups (Zn), binary dihedral groups corresponded to the symmetry group of regular 2n-gons, and binary polyhedral groups related to regular polyhedra. These are related to the classification of regular polyhedrons known as Platonic solids. There are five platonic solids (tetrahedron, cubic, octahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron), but, as a regular polyhedron and its dual polyhedron are associated with the same symmetry groups, there are only three binary polyhedral groups(binary tetrahedral group 2T, binary octahedral group 2O, binary icosahedral group 2I) related to regular polyhedrons. -

THE ZEN of MAGIC SQUARES, CIRCLES, and STARS Also by Clifford A

THE ZEN OF MAGIC SQUARES, CIRCLES, AND STARS Also by Clifford A. Pickover The Alien IQ Test Black Holes: A Traveler’s Guide Chaos and Fractals Chaos in Wonderland Computers and the Imagination Computers, Pattern, Chaos, and Beauty Cryptorunes Dreaming the Future Fractal Horizons: The Future Use of Fractals Frontiers of Scientific Visualization (with Stuart Tewksbury) Future Health: Computers and Medicine in the 21st Century The Girl Who Gave Birth t o Rabbits Keys t o Infinity The Loom of God Mazes for the Mind: Computers and the Unexpected The Paradox of God and the Science of Omniscience The Pattern Book: Fractals, Art, and Nature The Science of Aliens Spider Legs (with Piers Anthony) Spiral Symmetry (with Istvan Hargittai) The Stars of Heaven Strange Brains and Genius Surfing Through Hyperspace Time: A Traveler’s Guide Visions of the Future Visualizing Biological Information Wonders of Numbers THE ZEN OF MAGIC SQUARES, CIRCLES, AND STARS An Exhibition of Surprising Structures across Dimensions Clifford A. Pickover Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2002 by Clifford A. Pickover Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pickover, Clifford A. The zen of magic squares, circles, and stars : an exhibition of surprising structures across dimensions / Clifford A. Pickover. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-691-07041-5 (acid-free paper) 1. Magic squares. 2. Mathematical recreations. I. Title. QA165.P53 2002 511'.64—dc21 2001027848 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Baskerville BE and Gill Sans. -

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ?

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ? Branko Grünbaum Dedicated to Joe Malkevitch, an old friend and colleague, who was always partial to polyhedra Abstract. The simple question of the title has many different answers, depending on the kinds of faces we are willing to consider, on the types of polyhedra we admit, and on the symmetries we require. Known results and open problems about this topic are presented. The main classes of objects considered here are the following, listed in increasing generality: Faces: convex n-gons, starshaped n-gons, simple n-gons –– for n ≥ 3. Polyhedra (in Euclidean 3-dimensional space): convex polyhedra, starshaped polyhedra, acoptic polyhedra, polyhedra with selfintersections. Symmetry properties of polyhedra P: Isohedron –– all faces of P in one orbit under the group of symmetries of P; monohedron –– all faces of P are mutually congru- ent; ekahedron –– all faces have of P the same number of sides (eka –– Sanskrit for "one"). If the number of sides is k, we shall use (k)-isohedron, (k)-monohedron, and (k)- ekahedron, as appropriate. We shall first describe the results that either can be found in the literature, or ob- tained by slight modifications of these. Then we shall show how two systematic ap- proaches can be used to obtain results that are better –– although in some cases less visu- ally attractive than the old ones. There are many possible combinations of these classes of faces, polyhedra and symmetries, but considerable reductions in their number are possible; we start with one of these, which is well known even if it is hard to give specific references for precisely the assertion of Theorem 1. -

Fundamental Principles Governing the Patterning of Polyhedra

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE PATTERNING OF POLYHEDRA B.G. Thomas and M.A. Hann School of Design, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK. [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper is concerned with the regular patterning (or tiling) of the five regular polyhedra (known as the Platonic solids). The symmetries of the seventeen classes of regularly repeating patterns are considered, and those pattern classes that are capable of tiling each solid are identified. Based largely on considering the symmetry characteristics of both the pattern and the solid, a first step is made towards generating a series of rules governing the regular tiling of three-dimensional objects. Key words: symmetry, tilings, polyhedra 1. INTRODUCTION A polyhedron has been defined by Coxeter as “a finite, connected set of plane polygons, such that every side of each polygon belongs also to just one other polygon, with the provision that the polygons surrounding each vertex form a single circuit” (Coxeter, 1948, p.4). The polygons that join to form polyhedra are called faces, 1 these faces meet at edges, and edges come together at vertices. The polyhedron forms a single closed surface, dissecting space into two regions, the interior, which is finite, and the exterior that is infinite (Coxeter, 1948, p.5). The regularity of polyhedra involves regular faces, equally surrounded vertices and equal solid angles (Coxeter, 1948, p.16). Under these conditions, there are nine regular polyhedra, five being the convex Platonic solids and four being the concave Kepler-Poinsot solids. The term regular polyhedron is often used to refer only to the Platonic solids (Cromwell, 1997, p.53). -

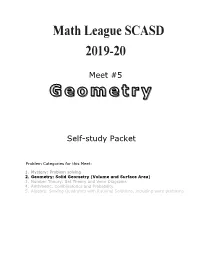

Geometrygeometry

Math League SCASD 2019-20 Meet #5 GeometryGeometry Self-study Packet Problem Categories for this Meet: 1. Mystery: Problem solving 2. Geometry: Solid Geometry (Volume and Surface Area) 3. Number Theory: Set Theory and Venn Diagrams 4. Arithmetic: Combinatorics and Probability 5. Algebra: Solving Quadratics with Rational Solutions, including word problems Important Information you need to know about GEOMETRY: Solid Geometry (Volume and Surface Area) Know these formulas! SURFACE SHAPE VOLUME AREA Rect. 2(LW + LH + LWH prism WH) sum of areas Any prism H(Area of Base) of all surfaces Cylinder 2 R2 + 2 RH R2H sum of areas Pyramid 1/3 H(Base area) of all surfaces Cone R2 + RS 1/3 R2H Sphere 4 R2 4/3 R3 Surface Diagonal: any diagonal (NOT an edge) that connects two vertices of a solid while lying on the surface of that solid. Space Diagonal: an imaginary line that connects any two vertices of a solid and passes through the interior of a solid (does not lie on the surface). Category 2 Geometry Calculator Meet Meet #5 - April, 2018 1) A cube has a volume of 512 cubic feet. How many feet are in the length of one edge? 2) A pyramid has a rectangular base with an area of 119 square inches. The pyramid has the same base as the rectangular solid and is half as tall as the rectangular solid. The altitude of the rectangular solid is 10 feet. How many cubic inches are in the volume of the pyramid? 3) Quaykah wants to paint the inside of a cylindrical storage silo that is 63 feet high and whose circular floor has a diameter of 19 feet. -

Putting the Icosahedron Into the Octahedron

Forum Geometricorum Volume 17 (2017) 63–71. FORUM GEOM ISSN 1534-1178 Putting the Icosahedron into the Octahedron Paris Pamfilos Abstract. We compute the dimensions of a regular tetragonal pyramid, which allows a cut by a plane along a regular pentagon. In addition, we relate this construction to a simple construction of the icosahedron and make a conjecture on the impossibility to generalize such sections of regular pyramids. 1. Pentagonal sections The present discussion could be entitled Organizing calculations with Menelaos, and originates from a problem from the book of Sharygin [2, p. 147], in which it is required to construct a pentagonal section of a regular pyramid with quadrangular F J I D T L C K H E M a x A G B U V Figure 1. Pentagonal section of quadrangular pyramid basis. The basis of the pyramid is a square of side-length a and the pyramid is assumed to be regular, i.e. its apex F is located on the orthogonal at the center E of the square at a distance h = |EF| from it (See Figure 1). The exercise asks for the determination of the height h if we know that there is a section GHIJK of the pyramid by a plane which is a regular pentagon. The section is tacitly assumed to be symmetric with respect to the diagonal symmetry plane AF C of the pyramid and defined by a plane through the three points K, G, I. The first two, K and G, lying symmetric with respect to the diagonal AC of the square. -

Sink Or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics

AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL 33 33 Sink or Float? Sink or Float: Thought Problems in Math and Physics is a collection of prob- lems drawn from mathematics and the real world. Its multiple-choice format Sink or Float? forces the reader to become actively involved in deciding upon the answer. Thought Problems in Math and Physics The book’s aim is to show just how much can be learned by using everyday Thought Problems in Math and Physics common sense. The problems are all concrete and understandable by nearly anyone, meaning that not only will students become caught up in some of Keith Kendig the questions, but professional mathematicians, too, will easily get hooked. The more than 250 questions cover a wide swath of classical math and physics. Each problem s solution, with explanation, appears in the answer section at the end of the book. A notable feature is the generous sprinkling of boxes appearing throughout the text. These contain historical asides or A tub is filled Will a solid little-known facts. The problems themselves can easily turn into serious with lubricated aluminum or tin debate-starters, and the book will find a natural home in the classroom. ball bearings. cube sink... ... or float? Keith Kendig AMSMAA / PRESS 4-Color Process 395 page • 3/4” • 50lb stock • finish size: 7” x 10” i i \AAARoot" – 2009/1/21 – 13:22 – page i – #1 i i Sink or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics i i i i i i \AAARoot" – 2011/5/26 – 11:22 – page ii – #2 i i c 2008 by The -

THE INVENTION of ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY 1. Introductory

THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY Christoph Lüthy Center for Medieval and Renaissance Natural Philosophy University of Nijmegen1 1. Introductory Puzzlement For centuries now, particles of matter have invariably been depicted as globules. These glob- ules, representing very different entities of distant orders of magnitudes, have in turn be used as pictorial building blocks for a host of more complex structures such as atomic nuclei, mole- cules, crystals, gases, material surfaces, electrical currents or the double helixes of DNA. May- be it is because of the unsurpassable simplicity of the spherical form that the ubiquity of this type of representation appears to us so deceitfully self-explanatory. But in truth, the spherical shape of these various units of matter deserves nothing if not raised eyebrows. Fig. 1a: Giordano Bruno: De triplici minimo et mensura, Frankfurt, 1591. 1 Research for this contribution was made possible by a fellowship at the Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschafts- geschichte (Berlin) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant 200-22-295. This article is based on a 1997 lecture. Christoph Lüthy Fig. 1b: Robert Hooke, Micrographia, London, 1665. Fig. 1c: Christian Huygens: Traité de la lumière, Leyden, 1690. Fig. 1d: William Wollaston: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1813. Fig. 1: How many theories can be illustrated by a single image? How is it to be explained that the same type of illustrations should have survived unperturbed the most profound conceptual changes in matter theory? One needn’t agree with the Kuhnian notion that revolutionary breaks dissect the conceptual evolution of science into incommensu- rable segments to feel that there is something puzzling about pictures that are capable of illus- 2 THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY trating diverging “world views” over a four-hundred year period.2 For the matter theories illustrated by the nearly identical images of fig. -

MAΘ Theta CPAV Solutions 2018

MAΘ Theta CPAV Solutions 2018 Since the perimeter of the square is 40, one side of the square is 10 & its area is 100. Since the 1. B diameter of the circle is 8 its radius is 4. One quarter of the circle is inside the square; its area is 1 1 퐴 = 휋(42) = 휋(16) = 4휋. The area inside the square but outside the circle is 100 − 4휋. 4 4 Since the diameter of the sphere is 20 feet, its radius is 10 feet. 4 4 4000휋 1200휋 푉 = 휋푟3 = 휋103 = ; 퐴 = 4휋푟2 = 4휋102 = 400휋 = ; 3 3 3 3 2. C 1200휋 4000휋 5200휋 퐴 + 푉 = + = 3 3 3 3. B Since the diameter is 18 퐶 = 휋푑 = 18휋 4. A 3 3 288 2 푉 = 푎 ⁄ = 12 ⁄ = 1728⁄ = 288⁄ = √ ⁄ = 144√2 6√2 6√2 6√2 √2 2 20 Use the given circumference to find the radius of the circle. 퐶 = 2휋푟, 40 = 2휋푟, 20 = 휋푟, ⁄휋 = 푟 . If the inscribed angle is 45∘ its arc is 90∘ and has length 10, one quarter of the circumference. The chord of the 5. D segment is the hypotenuse of an isosceles right triangle whose legs are radii of the circle. 20 20√2 ℎ = 푙푒√2 = ⁄휋 √2 = ⁄휋 20√2 Perimeter of the segment is arc length plus chord: 10 + ⁄휋 Since the diameter of the sphere is the space diagonal of the inscribed cube, we must first find the diameter of the sphere. 6. B 4 125휋 3 4 125휋(3√3) 125 27 5 3 푉 = 휋푟3; √ = 휋푟3; = 푟3; √ = 푟3; √ = 푟 and diameter is 5√3 3 2 3 8휋 8 2 Space diagonal of a cube is 푎√3 = 5√3; 푎 = 5 and surface area is 6푎2 = 6 ∙ 52 = 150 Radius found using the circular cross-section area 퐴 = 휋푟2; 9휋 = 휋푟2; 푟 = 3; ℎ = 3푟 == 9 Volume is equal to volume of cylinder minus volume of hemisphere.