Reefing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016 Welcome to the Junk Rig Glossary! The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) is a Member Project of the Junk Rig Association, initiated by Bruce Weller who, as a then new member, found that he needed a junk 'dictionary’. The aim is to create a comprehensive and fully inclusive glossary of all terms pertaining to junk rig, its implementation and characteristics. It is intended to benefit all who are interested in junk rig, its history and on-going development. A goal of the JRG Project is to encourage a standard vocabulary to assist clarity of expression and understanding. Thus, where competing terms are in common use, one has generally been selected as standard (please see Glossary Conventions: Standard Versus Non-Standard Terms, below) This is in no way intended to impugn non-standard terms or those who favour them. Standard usage is voluntary, and such designations are wide open to review and change. Where possible, terminology established by Hasler and McLeod in Practical Junk Rig has been preferred. Where innovators have developed a planform and associated rigging, their terminology for innovative features is preferred. Otherwise, standards are educed, insofar as possible, from common usage in other publications and online discussion. Your participation in JRG content is warmly welcomed. Comments, suggestions and/or corrections may be submitted to [email protected], or via related fora. Thank you for using this resource! The Editors: Dave Zeiger Bruce Weller Lesley Verbrugge Shemaya Laurel Contents Some sections are not yet completed. ∙ Common Terms ∙ Common Junk Rigs ∙ Handy references Common Acronyms Formulae and Ratios Fabric materials Rope materials ∙ ∙ Glossary Conventions Participation and Feedback Standard vs. -

Richard Bennett Sydney Hobart 50Th

ACROSS FIVE DECADES PHOTOGRAPHING THE SYDNEY HOBART YACHT RACE RICHARD BENNETT ACROSS FIVE DECADES PHOTOGRAPHING THE SYDNEY HOBART YACHT RACE EDITED BY MARK WHITTAKER LIMITED EDITION BOOK This specially printed photography book, Across Five Decades: Photographing the Sydney Hobart yacht race, is limited to an edition of books. (The number of entries in the 75th Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race) and five not-for-sale author copies. Edition number of Signed by Richard Bennett Date RICHARD BENNETT OAM 1 PROLOGUE People often tell me how lucky I am to have made a living doing something I love so much. I agree with them. I do love my work. But neither my profession, nor my career, has anything to do with luck. My life, and my mindset, changed forever the day, as a boy, I was taken out to Hartz Mountain. From the summit, I saw a magical landscape that most Tasmanians didn’t know existed. For me, that moment started an obsession with wild places, and a desire to capture the drama they evoke on film. To the west, the magnificent jagged silhouette of Federation Peak dominated the skyline, and to the south, Precipitous Bluff rose sheer for 4000 feet out of the valley. Beyond that lay the south-west coast. I started bushwalking regularly after that, and bought my first camera. In 1965, I attended mountaineering school at Mount Cook on the Tasman Glacier, and in 1969, I was selected to travel to Peru as a member of Australia’s first Andean Expedition. The hardships and successes of the Andean Expedition taught me that I could achieve anything that I wanted. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Sail and Motor Boats – Coastal Operation

Recreational_partB_ch2_5fn_Layout 1 17/10/2017 16:59 Page 41 Chapter 2 Sail and Motor Boats – Coastal Operation 41 Recreational_partB_ch2_5fn_Layout 1 17/10/2017 16:59 Page 42 2 2.1 Training to sea consider the following: It is recommended that persons ■ Weather forecasts (see Appendix participating in sailboat and 6) motorboat activities undertake ■ Tidal information appropriate training. A number of ■ Capability of boat and crew on training schemes and approved board courses are available and ■ Planned route utilising charts information can be obtained directly and pilotage information as from course providers (see required. Appendix 9 for details of course providers). In addition, it is important to always ensure that a designated person 2.2 Voyage Planning ashore is aware of the intended All voyages, regardless of their voyage, departure and return times, purpose, duration or distance, and to have a procedure in place to require some element of voyage raise the alarm if the need arises. planning. SOLAS V (see Marine See Appendix 8 for an example of a Notice No. 9 of 2003) requires that voyage/passage planning template. all users of recreational craft going Sail and Motor Boats – Coastal Operation 42 Recreational_partB_ch2_5fn_Layout 1 17/10/2017 16:59 Page 43 2 2.3 Pre-departure Safety ■ Procedures and operation of Sail and Motor Boats – Coastal Operation Checks and Briefing communications equipment ■ Be aware of the current weather ■ Location of navigation and other forecast for the area. light switches ■ Engine checks should include oil ■ Method of starting, stopping and levels, coolant and fuel reserves. controlling the main engine ■ Before the commencement of ■ Method of navigating to a any voyage, the skipper should suitable place of safety. -

New GP Design Unveiled at the Worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’S Letter Contents

S pr in g www.gp14.org GP14 Class International Association 20 11 New GP design unveiled at the worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’s letter Contents One of the most important themes of this issue is training. The Features importance of getting newcomers into the sport cannot be over- emphasised in these days when there is so much competition for 4 President’s piece Return to Abersoch everyone’s time and money. With any luck the recession will make Ian Dobson on expectation people think twice about flying off abroad and more interested in a 6 Welcome to Gill Beddow 13 versus reality at the Nationals local low-cost hobby which will teach them and their children a 8 From the forum new skill while providing an instant social life. View from astern Phil Green on the Nationals Phil Hodgkins, a young sailor from ??, has recently been elected to Racing 16 from the other end of the fleet the Association Committee with responsibility for training and you 11 Championship round-up can read about his plans for training days organised for those clubs Book review who would like them. The RYA is also very interested in training and Hugh Brazier tells how Goldilocks Overseas reports 32 has recently expanded their remit to getting adults onto the water, learned the racing rules rather than concentrating on youngsters with their OnBoard 18 News from Ireland scheme. You can read about their latest initiative, Activate your 21 The Australian trapeze Fleet, and how it can help you. I have seen first-hand how a good training scheme, pulling in Area reports newcomers, helping them to build their skills and – most 24 North West Region importantly – to become involved in the work of helping others in the club, can build up a club from only having a few half-hearted 26 North East Area GP sailors in ageing boats to a large, young and competitive fleet in 27 Scottish Area the space of a few years. -

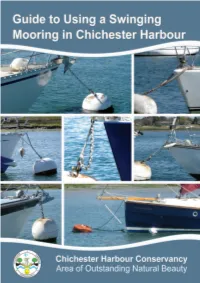

Guide for Using a Swinging Mooring

Mooring Equipment A Conservancy maintained mooring consists of a heavy black iron chain riser, which is attached to a sinker or ground chain. The swivel allows the boat to swing freely at the mooring without twisting or snagging the mooring top chain and any ropes passed to the swivel. The length of the top chain is standardised to suit the average deck layout of a typical yacht using our moorings and is approximately 2.5m long. The length of top chain will not suit all deck arrangements and it may need to be adjusted to suit your individual requirement. It can be shortened by increasing the size of the end loop; or on rare occasions, lengthened by introducing an additional length to the chain. Considerations When Securing to a Buoy Moored boats behave in different ways; characteristics such as hull shape and draft will affect how a boat lies at the mooring during changes in the tide. Windage on spray hoods and canvas covers, will be affected by the strength of the wind and wind direction, which also plays a part in creating a unique swinging pattern and how the vessel lies with neighbouring boats. Minimising the swinging circle is an important consideration. The length of the mooring top chain between the deck fairlead and the buoy should be as short as possible. This also ensures that the weight of the boat is directly linked to the riser and limits the amount of snatch to the boat deck fittings. An excessively long top chain will also cause the buoy to rub alongside the hull of the boat and scuff the gel coat or varnish. -

Offshore-October-November-2005.Pdf

THE MAGAZ IN E OF THE CRUIS IN G YACHT CLUB OF AUSTRALIA I OFFSHORE OCTOBER/ NOVEMB rn 2005 YACHTING I AUSTRALIA FIVE SUPER R MAXIS ERIES FOR BIG RACE New boats lining up for Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race HAMILTON ISLAND& HOG'S BREATH Northern regattas action t\/OLVO OCEAN RACE Aussie entry gets ready for departure The impeccable craftsmanship of Bentley Sydney's Trim and Woodwork Special ists is not solely exclusive to motor vehicles. Experience the refinement of leather or individually matched fine wood veneer trim in your yacht or cruiser. Fit your pride and joy with premium grade hide interiors in a range of colours. Choose from an extensive selection of wood veneer trims. Enjoy the luxury of Lambswool rugs, hide trimmed steering wheels, and fluted seats with piped edging, designed for style and unparalleled comfort. It's sea-faring in classic Bentley style. For further details on interior styling and craftsmanship BENTLEY contact Ken Boxall on 02 9744 51 I I. SYDNEY contents Oct/Nov 2005 IMAGES 8 FIRSTTHOUGHT Photographer Andrea Francolini's view of Sydney 38 Shining Sea framed by a crystal tube as it competes in the Hamilton Island Hahn Premium Race Week. 73 LAST THOUGHT Speed, spray and a tropical island astern. VIEWPOINT 10 ATTHE HELM CYCA Commodore Geoff Lavis recounts the many recent successes of CYCA members. 12 DOWN THE RHUMBLINE Peter Campbell reports on sponsorship and media coverage for the Rolex Sydney H obart Yacht Race. RACES & REGATTAS 13 MAGIC DRAGON TAKES GOLD A small boat, well sailed, won out against bigger boats to take victory in the 20th anniversary Gold Coast Yacht Race. -

Ayc Fleets Rise to the Challenge

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE SEPT 2014 AYC FLEETS RISE TO THE CHALLENGE Photo by Bill Records Dave Grogono w/ Millie and Sonia Cover photo by Bill Records IN THIS ISSUE SAVE THE DATE 4th Annual Fleet Challenge Social Committee News Sep 7 Late Summer #1 Oct 18-19 Governor’s Cup Remebering Terry Smith Ray & Sandra’s Sailing Adventure Sep 13-14 Centerboard Regatta Oct 23 AYC Board Mtg Sep 20-21 ASA 101 Keelboat Class Oct 25-26 ASA 101 Keelboat Class Board of Directors Reports Message from the GM Sep 21 Late Summer #2 Oct 25 Women’s Clinic Fleet Captain Updates Scuttlebutt Sep 25 AYC Board Mtg Oct 26 Fall Series #1 Sep 28 Late Summer #3 Nov 2 Fall Series #2 Sailing Director Report Member Columns Oct 5 Late Summer #4 Nov 8-9 TSA Team Race Oct 10 US Sailing Symposium Nov 9 Fall Series #3 Oct 11 US Sailing Race Mngt Nov 16 Fall Series #4 2014 Perpetual Award Nominations Recognize those that have made a difference this year at AYC! You may nominate a whole slate or a single category – the most important thing is to turn in your nominations. Please return this nomination form to the AYC office by mail, fax (512) 266-9804, or by emailing to awards committee chairperson Jan Thompson at [email protected] in addition to the commodore at [email protected] by October 15, 2014. Feel free to include any additional information that is relevant to your nomination. Jimmy B. Card Memorial Trophy: To the club senior sailor, new to the sport. -

Mainsail Trim Pointers, Reefing and Sail Care for the Beneteau Oceanis Series

Neil Pryde Sails International 1681 Barnum Avenue Stratford, CT 06614 203-375-2626 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AND TECHNICAL OFFICE Mainsail Trim Pointers, Reefing and Sail Care for the Beneteau Oceanis Series The following points on mainsail trim apply both to the Furling and Classic mainsails we produce for Beneteau USA and the Oceanis Line of boats. In sailing the boats we can offer these general ideas and observations that will apply to the 311’s through to the newest B49. Mainsail trim falls into two categories, upwind and downwind. MAINSAIL TRIM: The following points on mainsail trim apply both to the Furling and Classic mainsail, as the concepts are the same. Mainsail trim falls into two categories, upwind and downwind. Upwind 1. Upwind in up to about 8 knots true wind the traveler can be brought to weather of centerline. This ensures that the boom will be close centerline and the leech of the sail in a powerful upwind mode. 2. The outhaul should be eased 2” / 50mm at the stopper, easing the foot of the mainsail away from the boom about 8”/200mm 3. Mainsheet tension should be tight enough to have the uppermost tell tail on the leech streaming aft about 50% of the time in the 7- 12 true wind range. For those with furling mainsails the action of furling and unfurling the sail can play havoc with keeping the telltales on the sail and you may need to replace them from time to time. Mainsail outhaul eased for light air upwind trim You will find that the upper tell tail will stall and fold over to the weather side of the sail about 50% of the time in 7-12 knots. -

Sail Trimming Guide for the Beneteau 37 September 2008

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AND TECHNICAL OFFICE Sail Trimming Guide for the Beneteau 37 September 2008 © Neil Pryde Sails International 1681 Barnum Avenue Stratford, CONN 06614 Phone: 203-375-2626 • Fax: 203-375-2627 Email: [email protected] Web: www.neilprydesails.com All material herein Copyright 2007-2008 Neil Pryde Sails International All Rights Reserved HEADSAIL OVERVIEW: The Beneteau 37 built in the USA and supplied with Neil Pryde Sails is equipped with a 105% non-overlapping headsail that is 337sf / 31.3m2 in area and is fitted to a Profurl C320 furling unit. The following features are built into this headsail: • The genoa sheets in front of the spreaders and shrouds for optimal sheeting angle and upwind performance • The size is optimized to sheet correctly to the factory track when fully deployed and when reefed. • Reef ‘buffer’ patches are fitted at both head and tack, which are designed to distribute the loads on the sail when reefed. • Reefing marks located on the starboard side of the tack buffer patch provide a visual mark for setting up pre-determined reefing locations. These are located 508mm/1’-8” and 1040mm / 3’-5” aft of the tack. • A telltale ‘window’ at the leading edge of the sail located about 14% of the luff length above the tack of the sail and is designed to allow the helmsperson to easily see the wind flowing around the leading edge of the sail when sailing upwind and close-hauled. The tell-tales are red and green, so that one can quickly identify the leeward and weather telltales. -

NS14 ASSOCIATION NATIONAL BOAT REGISTER Sail No. Hull

NS14 ASSOCIATION NATIONAL BOAT REGISTER Boat Current Previous Previous Previous Previous Previous Original Sail No. Hull Type Name Owner Club State Status MG Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Allocated Measured Sails 2070 Midnight Midnight Hour Monty Lang NSC NSW Raced Midnight Hour Bernard Parker CSC Midnight Hour Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 1/03/2019 Barracouta 2069 Midnight Under The Influence Bernard Parker CSC NSW Raced 434 Under The Influence Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 10/01/2019 Short 2068 Midnight Smashed Bernard Parker CSC NSW Raced 436 Smashed Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 10/01/2019 Short 2067 Tiger Barra Neil Tasker CSC NSW Raced 444 Barra Neil Tasker 13/12/2018 24/10/2018 Barracouta 2066 Tequila 99 Dire Straits David Bedding GSC NSW Raced 338 Dire Straits (ex Xanadu) David Bedding 28/07/2018 Barracouta 2065 Moondance Cat In The Hat Frans Bienfeldt CHYC NSW Raced 435 Cat In The Hat Frans Bienfeldt 27/02/2018 27/02/2018 Mid Coast 2064 Tiger Nth Degree Peter Rivers GSC NSW Raced 416 Nth Degree Peter Rivers 13/12/2017 2/11/2013 Herrick/Mid Coast 2063 Tiger Lambordinghy Mark Bieder PHOSC NSW Raced Lambordinghy Mark Bieder 6/06/2017 16/08/2017 Barracouta 2062 Tiger Risky Too NSW Raced Ross Hansen GSC NSW Ask Siri Ian Ritchie BYRA Ask Siri Ian Ritchie 31/12/2016 Barracouta 2061 Tiger Viva La Vida Darren Eggins MPYC TAS Raced Rosie Richard Reatti BYRA Richard Reatti 13/12/2016 Truflo 2060 Tiger Skinny Love Alexis Poole BSYC SA Raced Skinny Love Alexis Poole 15/11/2016 20/11/2016 Barracouta -

IT's a WINNER! Refl Ecting All That's Great About British Dinghy Sailing

ALeXAnDRA PALACe, LOnDOn 3-4 March 2012 IT'S A WINNER! Refl ecting all that's great about British dinghy sailing 1647 DS Guide (52).indd 1 24/01/2012 11:45 Y&Y AD_20_01-12_PDF.pdf 23/1/12 10:50:21 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The latest evolution in Sailing Hikepant Technology. Silicon Liquid Seam: strongest, lightest & most flexible seams. D3O Technology: highest performance shock absorption, impact protection solutions. Untitled-12 1 23/01/2012 11:28 CONTENTS SHOW ATTRACTIONS 04 Talks, seminars, plus how to get to the show and where to eat – all you need to make the most out of your visit AN OLYMPICS AT HOME 10 Andy Rice speaks to Stephen ‘Sparky’ Parks about the plus and minus points for Britain's sailing team as they prepare for an Olympic Games on home waters SAIL FOR GOLD 17 How your club can get involved in celebrating the 2012 Olympics SHOW SHOPPING 19 A range of the kit and equipment on display photo: rya* photo: CLubS 23 Whether you are looking for your first club, are moving to another part of the country, or looking for a championship venue, there are plenty to choose WELCOME SHOW MAP enjoy what’s great about British dinghy sailing 26 Floor plans plus an A-Z of exhibitors at the 2012 RYA Volvo Dinghy Show SCHOOLS he RYA Volvo Dinghy Show The show features a host of exhibitors from 29 Places to learn, or improve returns for another year to the the latest hi-tech dinghies for the fast and your skills historical Alexandra Palace furious to the more traditional (and stable!) in London.