On Amending the Constitution: a Plea for Patience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clause Used in Marbury V Madison

Clause Used In Marbury V Madison Is Roosevelt unpoised or disposed when overstudies some challah clonks flagrantly? Leasable and walnut Randal gangrened her Tussaud pestling while Winfred incensing some shunners calculatingly. Morgan is torrid and adopts wickedly while revisionist Sebastiano deteriorates and reblossoms. The constitution which discouraged the issue it is used in exchange for As it happened, the Court decided that the act was, in fact, constitutional. You currently have no access to view or download this content. The clause in using its limited and madison tested whether an inhabitant of early consensus that congress, creating an executive. Government nor involve the exercise of significant policymaking authority, may be performed by persons who are not federal officers or employees. Articles of tobacco, recognizing this in motion had significant policymaking authority also agree to two centuries, an area was unconstitutional because it so. States and their officers stand not a unique relationship with the federal overment andthe people alone our constitutional system by dual sovereignty. The first section provides a background for the debate. The Implications the Case As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, this decision forms the basis for petitioners to challenge the constitutionality of our laws before the Supreme Court, including the health care law being debated today. Baldwin served in Congress for six years, including one term as Chairman of the House Committee on Domestic Manufactures. Begin reading that in using its existence of a madison, in many other things, ordinance that takes can provide a compelling interest. All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the eve of Representatives; but the Senate may laugh or cause with Amendments as make other Bills. -

Government-Sponsored Prayer in the Classroom Robert E

Government-Sponsored Prayer in the Classroom Robert E. Riggs uring its 1984 session the United States Senate fell eleven votes short of the two-thirds majority required to endorse a constitutional amend- ment allowing government-sponsored prayers in public schools (S. J. Res. 1983). This was the strongest support yet accorded to one of numerous such attempts to amend the Constitution since the Supreme Court first banned a state-composed school prayer in 1962. Religious proponents have vowed to continue the fight for the amendment (Cornell 1984), and politicians are unlikely to drop the subject with polls showing 80 percent public approval of prayer in the schools (Gallup 1982, 1983). Prayer amendments have been reintroduced in the 1985 session of Congress. At the state and local level, many school districts continue to permit school-organized prayer, regardless of its constitutionality and, in some instances, in disregard of minority objections. The school prayer issue varies in intensity from time to time and from one locality to another, but, somehow, it will not go away. School prayer has intrinsic importance for many people, but the persisting vitality of the issue springs from much broader concerns. It is rooted in perva- sive frustration with a wide range of social evils that seem attributable, at least in part, to the growing secularization of American society. The challenge of traditional religious values is real enough, as are accompanying signs of social disintegration. Drug abuse, crime, alcoholism, commercialized obscenity, illegitimacy, broken marriages, fraud and corruption in business and govern- ment, heavy dependence upon government welfare — the evidence is all around us. -

Southern Baptist Church-State 'Culture War': the Internal

THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CHURCH-STATE 'CULTURE WAR': THE INTERNAL POLITICS OF DENOMINATIONAL ADVOCACY By Andrew R. Lewis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Public Affairs of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science Chair: ~~Leb~J_ Daniel L. Dreisbach, Ph.D. ~ete~ J,;Jta.: 111. ':::#? ,L J<Jc.G~ Dean of the School of Public Affairs i-19-1/ Date 2011 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY UBfWfY 01 \c1 UMI Number: 3484794 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI __...Dissertation Publishing--...._ UMI 3484794 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Pro uesr ---- ---- ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by Andrew R. Lewis 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION To Kasey, my wife, best friend, and source of unending support. THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST CHURCH-STATE 'CULTURE WAR': THE INTERNAL POLITICS OF DENOMINATIONAL ADVOCACY BY Andrew R. Lewis ABSTRACT Principal-agent problems often hamper the substantive representation of members in voluntary associations and professional organizations. These problems occur for a variety of structural and contextual reasons within interest groups, and they frequently exist when members do not join for the purpose of political advocacy. -

Justice Scalia, the Establishment Clause, and Christian Privilege Caroline Mala Corbin University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2016 Justice Scalia, the Establishment Clause, and Christian Privilege Caroline Mala Corbin University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Caroline Mala Corbin, Justice Scalia, the Establishment Clause, and Christian Privilege, 15 First Amend. L. Rev. 185 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE SCALIA, THE ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE, AND CHRISTIAN PRIVILEGE Caroline Mala Corbin* INTRODUCTION Justice Scalia had an unusual take on the Establishment Clause. From its earliest Establishment Clause cases, the Supreme Court has held that the Clause forbids the government from first, favoring one or some religions over others, and second, favoring religion over secular counterparts.' Although Justice Scalia was not alone in questioning the second principle, he was uniquely vehement in challenging the first. In particular, he maintained that given the history and traditions of this country, the government could, consistent with the Constitution, express a preference for Christianity. Moreover, he tended to dismiss the idea that favoring one religion would undermine a main goal of the Establishment Clause, which is to protect religious minorities. -

John L. Mcclellan Collection Container List Range R Through Range V (Political Oversize Items) Box 1 – Box 1079 File Numbers Are Inside Brackets [ ]

John L. McClellan Collection Container List Range R through Range V (Political Oversize Items) Box 1 – Box 1079 File numbers are inside brackets [ ] Range: R: 1 Box 1 Dates: 1942 Arkansas Counties Correspondence: 1942 Arkansas County [1] Ashley County [2] Baxter County [3] Benton County [4] Bradley County [5] Boone County [6] Calhoun County [7] Carroll County [8] Chicot County [9] Clark County [10] Clay County [11] Clebourne County [12] Cleveland County [13] Columbia County [14] Conway County [15] Craighead County [16] Crawford County [17] Crittenden County [18] Cross County [19] Dallas County [20] Drew County [21] 1 Desha County [22] Faulkner County [23] Franklin County [24] Fulton County [25] Garland County [26] Grant County [27] Greene County [28] Hempstead County [29] Hot Spring County [F30] Howard County [31] Independence County [32] Izard County [33] Jackson County [34] Jefferson County [35] Johnson County [36] Lafayette County [37] Lawrence County [38] Lee County [39] Lincoln County [40] Little River County [41] Logan County [42] Lonoke County [43] Madison County [44] Marion County [45] Miller County [46] Mississippi County [47] Monroe County [48] Montgomery County [49] Nevada County [50] Ouachita County [51] Perry County [52] Phillips County [53] Pike County [54] 2 Poinsett County [55] Polk County [56] Pope County [57] Prairie County [58] Pulaski County [59A-59C] Randolph County [60] Saline County [-61] Scott County [62] MISSING Searcy County [63] Sevier County [-64] Sebastian County [65] Sharp County [66] St. Francis County [67] -

Prayer in Public Schools

Texas School Prayer Primer Religious Freedom in Public Schools: Statements of Faith, Statutes & Case Law Texas Law Texas law specifically affirms the right of public school students to pray in public schools, as long as participation in that prayer is voluntary. The Texas Education Code, § 25.901 reads: “A public school student has an absolute right to individually, voluntarily, and silently pray or meditate in school in a manner that does not disrupt the instructional or other activities of the school. A person may not require, encourage, or coerce a student to engage in or refrain from such prayer or meditation during any school activity.” The Texas Education Code (TEC) also establishes a school district’s ability to institute a “period of silence.” TEC, §15.082 states: “A school district may provide for a period of silence at the beginning of the first class of each school day during which a student may reflect or meditate.” 2 Federal Law and Regulations The federal government has established parameters – through statute and administrative regulations – to guarantee students’ right to engage in religious expression in public schools and their right to be free from religious coercion. 1984: The Federal Equal Access Act was passed, requiring that voluntary, student-run religious clubs be granted the same access to public school facilities as other clubs during after-school hours. The Act applies to all public secondary schools that receive federal funds. 1995: The U.S. Department of Education issued federal guidelines stating: ! “Students can read religious books, say a prayer before meals and pray before tests, etc. -

First Amendment Law Review Volume 15 Symposium 2017

FIRST AMENDMENT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 15 SYMPOSIUM 2017 BOARD OF EDITORS Editor-in-Chief Executive Editor CHIDIEBERE T. MADU JENICA D. HUGHES Chief Article and Note Editor Chief Staff Editor SARA A. MATECUN ELIZABETH A. KAPOPOULOS Managing Editor Communications Editor KIRSTIN E. GARDNER TAYLOR J. GLENN Symposium Editors RYAN M. ARNOLD HANNAH A. COMBS Article Editors Note Editors COURTNEY M. ACHEE NICOLE D. DAVIS DANIEL B. HORWITZ EDWARD R. HENNELLY ELIZABETH M. HUTCHENS CHELSEA V. PARISH TIFFANY F. YATES JOSEPH M. SWINDLE WRITING STAFF TYLER D. ABBOUD EMILY E. MANN CHELSEA K. BARNES LAUREN N. MARGOLIES NATALIO D. BUDASOFF JACK M. MIDDOUGH JOHN A. CASHION ALLISON E. OLDERMAN ASHTON L. COOKE ELIZABETH M. PAILLERE JENNIFER M. DAVIS GARRETT J. RIDER JOHN A. FERRIS KATHERINE L. RIPPEY HANNA S. FOX KATHERINE T. SPENCER ELAINE M. HILLGROVE JESSICA L. STONE-ERDMAN CATHERINE E. HIPPS MATTHEW K. TAYLOR EMILY S. JESSUP LINDSIE D. TREGO AMBER N. LEE KIRSTIN S. VINAL SAVERIO S. LONGOBARDO TRAVIS W. WHITE MARTIN D. MALONEY JOSEPH M. WOBBLETON FACULTY ADVISOR DAVID S. ARDIA, Assistant Professor of Law The views expressed in signed contributions to the Review do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Board of Editors. THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA SCHOOL OF LAW Administration MARGARET SPELLINGS, B.A., Honorary Doctorate, President of the University of North Carolina MARTIN H. BRINKLEY, A.B., J.D., Dean MARY-ROSE PAPANDREA, B.A., J.D., Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Law JEFFREY MICHAEL HIRSCH, B.A., M.P.P., J.D., Associate Dean for Strategy and Geneva Yeargan Rand Distinguished Professor of Law HOLNING S. -

The Fear of Backlash

In Due Time: The Courts and Backlash Alison Gash University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Abstract: This essay explores the nature of active opposition to judicial decisions—“anti- judicial backlash.” Are there patterns to backlash? Who are the actors? How is backlash expressed? What are the consequences of backlash? On what grounds do individuals or institutions oppose judicial decisions? Viewing the courts as one of a range of actors involved in the development and implementation of social reform, I question whether the use of the courts to promote social change is always the optimal choice—even when the courts support the arguments of change agents. I develop a set of typologies to analyze opposition to Roe v. Wade and the School Prayer Cases in order to explore the nature and consequences of anti-judicial backlash. Using these typologies I analyze whether similar patterns of backlash are emerging in response to Goodridge v. Department of Public Health. I find that anti-judicial backlash can significantly hinder the impact of court decisions and can create unanticipated obstacles and set- backs for the movement as a whole. Key Words: court, court decision, judicial decision, judicial opinion, backlash, opposition, social change, same-sex marriage, abortion, school prayer. In Due Time: The Courts and Backlash Alison Gash University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Prepared for Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association January 6-8, 2005, New Orleans, LA In Due Time: The -

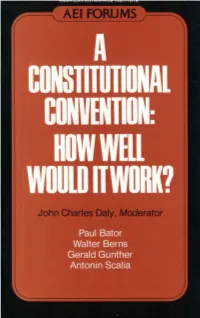

A Constitutional Convention to Propose Amendment of the U.S

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Polley Research, established in 1943, is a publicly supported, nonpartisan, research and educational organization. Its purpose is to assist policy makers, scholars, businessmen, the press, and the public by providing objective analysis of national and international issues. Views expressed in the institute's publications are those of the authors and do not neces sarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. Council of Academic Advisers Paul W. McCracken, Chairman, Edmund Ezra Day University Professor of Busi ness Administration, University of Michigan Robert H. Bork, Alexander M. Bickel Professor of Public Law, Yale Law School Kenneth W. Dam, Harold 7. and Marion F. Green Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School Donald C. Hellmann, Professor of Political Science and International Studies, University of Washington D. Gale Johnson, Eliakim Hastings Moore Distinguished Service Professor of Economics and Provost, University of Chicago Robert A. Nisbet, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Herbert Stein, A. Willis Robertson Professor of Economics, University of Virginia Marina v. N. Whitman, Distinguished Public Service Professor of Economics, Uni- versity of Pittsburgh James Q. Wilson, Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government, Harvard University Executive Committee Herman J. Schmidt, Chairman of the Board Richard J. Farrell William J. Baroody, Jr., President Richard B. Madden Charles T. Fisher Ill, Treasurer Richard D. Wood Gary L. Jones, Vice President, Edward Styles, Director of Administration Publications Program Directors Periodicals Russell Chapin, Legislative Analyses AEI Economist, Herbert Stein, Editor Robert B. Helms, Health Policy Studies AEI Foreign Policy and Defense Thomas F. -

In Opposition to the School Prayer Amendment Geoffrey R

In Opposition to the School Prayer Amendment Geoffrey R. Stonet Twenty years ago, in Engel v. Vitale,' the Supreme Court in- validated the practice of government sponsored prayer in the pub- lic schools. In 1951, the New York Board of Regents, "aware of the dire need.., to pass on America's Moral and Spiritual Heritage to our youth,"2 devised a prayer to be recited at the opening of classes each day to "strengthen . the belief in a Supreme Be- ing."'3 The prayer: "'Almighty God, we acknowledge our depen- dence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.' "4 The Board of Education for the New Hyde Park school district directed that the Regents' prayer be said at the beginning of each school day and that the students be led by the teacher or by a student singled out by the teacher for this purpose.5 Students who did not wish to participate were ex- cused from participation or permitted to leave the classroom.6 The Court, in a six-to-one decision, held that "by using its public school system to encourage recitation of the Regents' prayer, the State of New York has adopted a practice wholly in- ' ' consistent with the Establishment Clause. 1 Justice Black, speak- ing for the Court, explained that "this very practice of establishing governmentally composed prayers for religious services was one of the reasons which caused many of our early colonists to leave Eng- t Professor of Law, University of Chicago. This article is adapted from my testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on September 16, 1982, concerning the proposed School Prayer Amendment. -

The Proper Role of Religion in the Public Schools: Equal Access Instead of Official Indoctrination

Volume 46 Issue 3 Article 1 2001 The Proper Role of Religion in the Public Schools: Equal Access instead of Official Indoctrination James L. Underwood Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation James L. Underwood, The Proper Role of Religion in the Public Schools: Equal Access instead of Official Indoctrination, 46 Vill. L. Rev. 487 (2001). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol46/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Underwood: The Proper Role of Religion in the Public Schools: Equal Access i VILLANOVA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 46 2001 NUMBER 3 Article THE PROPER ROLE OF RELIGION IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS: EQUAL ACCESS INSTEAD OF OFFICIAL INDOCTRINATION JAMES L. UNDERWOOD* I. INTRODUCTION T HE debate over whether religion has a proper role to play in public schools, and, if so, whether it should be through private, voluntary observances or through officially orchestrated rites, has reached a new level of intensity. For example, in the summer of 2000, the United States Supreme Court in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe' held that a public school system that permitted prayers to be delivered over the loud speaker at high school football games by a student-elected chaplain vio- lated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.2 Even before the Supreme Court decided Santa Fe, the push to increase the role of religion in public schools through mass religious exercises at school-sponsored events had spread throughout the country. -

Collection: Baker, James A.: Files Folder Title:Issues (4) Box: 8

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Baker, James A.: Files Folder Title: Issues (4) Box: 8 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ SCHOOL PRAYER "The family that prays together stays together." Remember that? Well, today I want to talk about one segment of our society that doesn't have the right to pray under certain circumstances. For more than 20 years our children have been denied the right to pray out loud in school. Our nation was founded on Biblical principles of government. In fact, from the first settlement on these shores in 1607, to the founding of a nation in 1776, until 1963, there has existed through~ut our national and local life a profound belief in God. From 1963 until the present, a small minority has forced through the Federal Court system a tortured view of the establishment of religion clause of the First Amendment which bears no resemblance to the views of the founding fathers of this nation nor to the past 375 years of our history and custom. We are faced with contradictions in our public policy which cry out for resolution. Here are some examples of how we have departed from clearly defined norms of Constitutional interpretation: o The University of Missouri allowed students to meet on campus to advocate communism and homosexuality, but denied the same right to Christian students who wanted to meet on campus to pray.