Modeling Evacuate Versus Shelter-In-Place Decisions in Wildfires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(“BLWM”) Is a Regional Law Firm with Offices in Scottsdale, Arizona, Las Vegas, Nevada and Portland, Oregon

Bauman Loewe Witt & Maxwell, PLLC (“BLWM”) is a regional law firm with offices in Scottsdale, Arizona, Las Vegas, Nevada and Portland, Oregon. Its attorneys practice in the western United States, with attorneys currently licensed to practice law in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Texas and Washington. BLWM devotes its practice to investigation, resolution and management of complex litigation. Our goal is to provide our clients with cost-effective and creative solutions tailored to the client's needs, cost containment and unparalleled results. Included within our broad range of litigation services are our multi-state large loss property subrogation program, construction defect litigation, and general litigation for insurance companies and businesses. In addition to the substantive areas of law where they practice, our attorneys also are trained in forensic failure analysis, evidence acquisition and retention, forensic photography, property and liability insurance, products liability, code compliance, expert selection, and fire cause and origin determinations. We provide our clients with a full array of litigation related services ranging from oversight of forensic investigations, litigation in state and federal courts, mediations, and arbitration or trial services. We are not a traditional insurance firm. BLWM does not try to be everything to every client. Rather we limit our practice to areas that are complimentary of the other areas in which we practice. We leverage this experience to direct, contain and control the cases we handle to produce results consistent with our clients' expectations and entitlement. Our practice areas are described in detail in the pages that follow. In addition, you can learn more about our attorneys in the following pages, or by visiting www.blwmlawfirm.com. -

Fire Protection

3.6 FIRE PROTECTION 3.6 FIRE PROTECTION The following section describes fire protection resources and issues for the existing conditions of the subject site and vicinity; and evaluates impacts of the proposed project on these resources. Fire protection resources include the entities tasked with combating fires, infrastructure that assists those entities, and site conditions that contribute to or diminish the danger of fire. Fire protection issues in the eastern Montecito consist of high fire hazards related to wildfires and the distance of existing residences from fire stations, as well as their length of emergency response times. Assessment of fire protection issues is based upon a range of sources. These include the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1710, Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments. In addition, information and standards were also obtained from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE), as well as the Santa Barbara County Fire Department (SBCFD) and Los Padres National Forest. Montecito Fire Protection District (MFPD) staff was consulted regarding fire protection and response time issues. Finally, this section also includes updated information from the MFPD’s 2014 Standards of Coverage Study and Risk Assessment (MFPD 2014). 3.6.1 Existing Conditions 3.6.1.1 Regional Fire Danger On average, a major wildland fire occurs in the Santa Barbara area approximately every 3.5 years (Table 3.6-1). As a result of weather conditions, plant types, and past fire management policies, the Santa Ynez Mountains and surrounding area have a very high risk of fire. -

RVFD Annual Report 2008

Table of Contents: Letter from the Chief 2 Communities Served 3 Year in Review 4 Department Goals – 2009 5 Personnel by Shift 6 Personnel Achievements 7 Organizational Chart 8 Department Personnel – by years of service 9 Apparatus and Equipment Report 10 Training Division Report 11 Prevention Bureau Report 12 CERT and Get Ready Update 13 Incident Response Statistics 14 Incident Response Maps 16 Mutual and Auto Aid Report 19 Strike Team Assignments 20 Photos of Our Year 22 Published in May, 2009 Design, Editor, Layout: JoAnne Lewis, Administrative Assistant Review and Editorial Input: Roger Meagor, Fire Chief All photos included in this report were taken by Ross Valley Fire Department personnel. 1 Letter from the Chief Fire Chief Roger Meagor May 14, 2009 To Members of the Fire Board and the Ross Valley Community: On behalf of the members of the Ross Valley Fire Department (RVFD), I am pleased to present the 2008 Annual Report. This is the first Annual Report produced by our department in many years. We felt that it was important to bring this back to illustrate just how our department works. In 2008, RVFD entered a new chapter in its history. After the devastating floods of December, 2005, and moving into “temporary” trailers behind our uninhabitable fire station, 2008 saw the beginning of the reconstruction and remodel of Station 19. The department is excited at the prospect of moving back into the Station. The addition of new office space, dorms, shop, and storage space will assist the department in moving forward. In January, another series of storms battered our jurisdiction which brought us dangerously close to flooding once again. -

A Defensible Community?

A Retrospective Study of Montecito Fire Protection District’s Wildland Fire Program during the 2017 Thomas Fire October 23, 2018 A DEFENSIBLE COMMUNITY? | P a g e This page intentionally left blank. i | P a g e Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................1 Methods .................................................................................................................................................................1 The Community of Montecito ................................................................................................................................3 History of Montecito’s Wildland Fire Program Policy and Actions ........................................................................5 Existing Emergency Preparedness Programs and Community Education ..........................................................7 Structures ...............................................................................................................................................................8 The Wildfire Environment – pre-Thomas Fire ............................................................................................................8 Weather ..................................................................................................................................................................8 -

Wildland Urban Interface Fire Protection Research Colloquium

This space for GIS map depicting WUI Fire impacted states to be on inside cover Proceedings of the Wildland Urban Interface Fire Protection Research Colloquium California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA June 17-18, 2009 Cover photo: San Diego Union-Tribune Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, equipment, or services does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United states Government or the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), or any of its employees or contractors. This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Homeland Security under Award Number: 2008-ST-061-ND 0001. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the US Department of Homeland Security. Wildland Urban Interface Fire Protection Colloquium Preface The Wildland Urban Interface Fire Colloquium, held June 17-18, 2009, was one in a series of four hazards colloquia co-sponsored and funded by two Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology (DHS S&T) Directorate organizations, the Infrastructure and Geophysical Division (IGD) and the Office of University Programs (OUP). Other Colloquia in this series addressed coastal hazards (December 2008), geotechnical earthquake engineering (July 2009) and tsunamis (October 2009). Each hazards colloquium convened scientists, academics, and policy-makers to discuss the current state of research and identify knowledge gaps. Topics centered around the phenomenology of natural hazards and the impact of natural hazards on the built and natural environment. The outcomes of the colloquia were used to assemble individual Proceedings reports similar to the document you are about to read. -

Introduction

Introduction Personnel Assigned to Air Operations • Air Operations Chief • Director of maintenance • 3 Shift Captains • 3 Senior Pilots • 9 Pilots • 18 Firefighter Paramedics • 3 Lead mechanics • 9 Mechanics • Qualified relief • Additional support staff Aircraft Assigned to Air Operations • 5 B-412’s (360 gal tank MGW 11,900) • 3 S-70 Fire hawks (1,000 gal tank MGW 23,500) • Multi-mission configuration • Hoist capable • IAW L.A. County DHS defined as Air Ambulance • 3 person Crew (2 FFPM, 1 Pilot) • 3 Air Squads daily • Augmented staffing during fire season Flight Operations conducted 24/7 Los Angeles County Demographics: • Population 10,393,185 • Most of Population Lives on the Coastal Plain Between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel Mountains • 4081 Square Miles • 75 Miles of Coastline plus Catalina & San Clemente Islands • 50% of County is Mountainous Terrain Highest Point – Mount Baldy at 10,064 feet • Northern Third of County is Part of the Mojave Desert • Total Hours Flown: 2,700-3,000 annually • NVG Hours flown: • Hoist Rescues: average 80-100 annually • Trauma calls: • Vegetation Fires: 1335 Surrounding Agencies with Night Vision Goggle Programs • LA City Fire • Ventura County Sheriff/Fire • Santa Barbara County Sheriff/Fire • Kern County Fire • Orange County Fire • San Diego City Fire • USFS H-531 ANF Air Operations NVG History 1976- Generation I Night Vision Goggles utilized through a joint program with the USFS 1977- Mid-Air collision with a USFS contract helicopter at night on the Middle Fire, LAC stopped the NVG program -

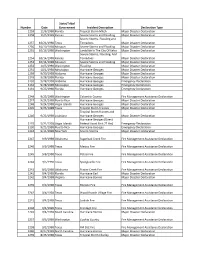

Identification of Disaster Code Declaration

State/Tribal Number Date Government Incident Description Declaration Type 1259 11/6/1998 Florida Tropical Storm Mitch Major Disaster Declaration 1258 11/5/1998 Kansas Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration Severe Storms, Flooding and 1257 10/21/1998 Texas Tornadoes Major Disaster Declaration 1256 10/19/1998 Missouri Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1255 10/16/1998 Washington Landslide In The City Of Kelso Major Disaster Declaration Severe Storms, Flooding, And 1254 10/14/1998 Kansas Tornadoes Major Disaster Declaration 1253 10/14/1998 Missouri Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1252 10/5/1998 Washington Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1251 10/1/1998 Mississippi Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1250 9/30/1998 Alabama Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1249 9/28/1998 Florida Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 3133 9/28/1998 Alabama Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 3132 9/28/1998 Mississippi Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 3131 9/25/1998 Florida Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 2248 9/25/1998 Washington Columbia County Fire Management Assistance Declaration 1247 9/24/1998 Puerto Rico Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1248 9/24/1998 Virgin Islands Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1245 9/23/1998 Texas Tropical Storm Frances Major Disaster Declaration Tropical Storm Frances and 1246 9/23/1998 Louisiana Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration Hurricane Georges (Direct 3129 9/21/1998 Virgin Islands Federal -

Municipal Code Chapter 8.04 Ordinance No. 5920

ORDINANCE NO. 5920 AN ORDINANCEOF THE COUNCILOF THE CITi' OF SANTA BARBARA AMENDING CHAPTER 8. 04 OF THE MUNICIPAL CODEAND ADOPTING BY REFERENCETHE 2018 EDITION OF THE INTERNATIONAL FIRE CODE, INCLUDING APPENDIXCHAPTER 4 AND APPENDICES B, BB, C, CC, AND H OF THAT CODE, AND THE 2019 CALIFORNIAFIRE CODEWITH LOCALAMENDMENTS TO BOTH CODES. THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SANTA BARBARA DOES ORDAIN AS FOLLOWS: SECTION 1. Findings. Climatic Conditions A. The City of Santa Barbara is located in a semi-arid Mediterranean type climate. It annually experiences extended periods of high temperatures with little or no precipitation. Hot, dry winds, ("Sundowners") which may reach speeds of 60 m. p. h. or greater, are also common to the area. These climatic conditions cause extreme drying of vegetation and common building materials. In addition, the high winds generated often cause road obstructions such as fallen trees. Frequent periods of drought and low humidity add to the fire danger. This predisposes the area to large destructive fires. In addition to directly damaging or destroying buildings, these fires also disrupt utility services throughout the area. The City of Santa Barbara and adjacent front country have a history of such fires, including the 1990 Painted Cave Fire and the 1977 Sycamore Canyon Fire. In 2007, the City was impacted by the back country Zaca Fire and by the Gap fire in 2008. The Tea Fire destroyed over 150 homes within the City in November of 2008 and the Jesusita Fire destroyed homes and property in much of the Santa Barbara front country in May of 2009. -

Fire Safety by Introducing and Exposing the Public and Firefighters to Known Hazards

9222 Lake Canyon Road Santee, CA 92071 March 9, 2015 Orange County Board of Supervisors Todd Spitzer, Chairman Lisa A. Bartlett, Vice Chair Andrew Do Shawn Nelson Michelle Steel 333 W. Santa Ana Blvd, Room 465 P.O. Box 687 Santa Ana, CA 92702-0687 Via email [email protected] RE: Esperanza Hills Project (PA120037) / FEIR No. 661 Significant Adverse Impacts to Public Safety Dear Board of Supervisors, Please review these expert comments submitted on behalf of Protect Our Homes & Hills. The location and site design of the Esperanza Hills Project significantly impacts fire safety by introducing and exposing the public and firefighters to known hazards. Firefighters with adequate safety zones can defend structures threatened by wildlfire under certain conditions, however both the availability of firefighting resources and the location of adequate safety zones are in question for Esperanza Hills during major incidents in Southern California. The hazards are amplified by the high probability that the project cannot be evacuated prior to Santa Ana wind driven fire fronts that reach the site. Furthermore, attempts to evacuate the project will significantly impact the ability of older existing structures in the vicinity to be evacuated. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group “Incident Response Pocket Guide” (IRPG)1 is the standard for fighting wildland and wildland-urban-interface fires. Dispatching firefighters to fight wildland fires on and adjacent to the Esperanza Hills Project will place firefighters in situations where they will be required to either ignore the standards of the IRPG or abandon suppression tactics on site. 1 National Wildfire Coordinating Group “Incident Response Pocket Guide”, PMS 461, NFES 001077, January 2014, p.13. -

2021 Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP)

CITY OF SANTA BARBARA February 2021 Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled material. Table of Contents SECTIONS Acronyms and Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................................... vii 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Development Team ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Community Involvement ................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3.1 Stakeholders ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3.2 Public Outreach and Engagement Plan ........................................................................................................ 4 1.3.3 Public Outreach Meetings ............................................................................................................................. -

Calendar and Guidebook for Los Angeles County Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes in the Wildland-Urban Interface D

Calendar and Guidebook for Los Angeles County Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes in the Wildland-Urban Interface d SAFE LANDSCAPES PROJECT The SAFE Landscapes (Sustainable And Fire SafE) calendar provides guidelines for creating and maintaining fire-safe, environmentally-friendly landscapes in the wildland-urban interface. This project is a collaboration between the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers Watershed Council, University of California Cooperative Extension – Los Angeles and Ventura Counties, the Los Angeles County Fire Department, numerous governmental, non-profit, and business organizations (listed on the inside back cover) with support from the California Community Foundation and the National Park Service. Fire safety in the wildland-urban interface starts with good practices to avoid starting fires in and around the home. These practices include the use of ignition-resistant building materials and architectural features and the development of a fire-resistant landscape, where plants and hardscape are maintained so that they do not easily transmit fire. Establish your defensible Los Angeles County Fire Department Angeles County Fire Los space so that the risk of fire transmission to your property is reduced and fire fighters can safely protect your home. There is no way to completely ensure that your home will not be exposed to wildfire. If you live in a fire hazard severity zone in the wildland-urban interface, it is not a question of IF a fire will occur, but WHEN. Preparation for wildfire requires that YOU take responsibility for your safety, property, and pets in the event of a fire. Maintain your property to reduce the risk of damage during a wildfire, and be fully prepared to evacuate. -

Download Event History

SANTA BARBARA EQUINE ASSISTANCE AND EVACUATION TEAM, INC. Services and Disaster Event History The Santa Barbara Equine Assistance and Evacuation Team, Inc. (Equine Evac) is a volunteer group whose members are registered by the Office of Emergency Services as Disaster Service Workers. We are also a registered Non-Profit organization with a 501c3 designation. The Equine Evac Team has equipment and personnel available for large animal evacuation, billeting and rescue. Members of the Team have also completed the Incident Command System (ICS) course and have received the Standardized Emergency Management System certificate. We conduct periodic training sessions on the transporting and housing of animals during emergencies. All requests for emergency assistance are channeled through the Sheriff's Dispatch (911), who notify County Animal Services and then determine the extent of Team activation. On the scene, the Equine Evac Team Agency Representative reports to and operates under the direction of the Liaison Officer or the Incident Command and our Animal Services Representative. All animals are sheltered free of charge and there are no paid staff. Equine Evac sponsors clinics and provides in-service training for interested community groups and its volunteers on such topics as barn safety, trailering, and animal safety and evacuation. Over the last 30 years we have been extremely appreciative of the Earl Warren Showgrounds administration and staff in supporting the many evacuations that have occurred. These events have required the housing of animals for not just our county but in many mutual aid situations which have required the availability of stalls for evacuated animals. To date we have sheltered over 4300 animals.