Captain Scott Was an Inept Polar Explorer. Yet 100 Years on from His Final, Fatal Polar Expedition, Scott’S Story – and the Pole Itself – Continue to Fascinate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

2. Disc Resources

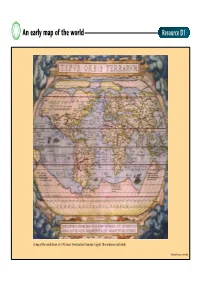

An early map of the world Resource D1 A map of the world drawn in 1570 shows ‘Terra Australis Nondum Cognita’ (the unknown south land). National Library of Australia Expeditions to Antarctica 1770 –1830 and 1910 –1913 Resource D2 Voyages to Antarctica 1770–1830 1772–75 1819–20 1820–21 Cook (Britain) Bransfield (Britain) Palmer (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Resolution and Adventure Williams Hero 1819 1819–21 1820–21 Smith (Britain) ▼ Bellingshausen (Russia) Davis (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ Williams Vostok and Mirnyi Cecilia 1822–24 Weddell (Britain) ▼ Jane and Beaufoy 1830–32 Biscoe (Britain) ★ ▼ Tula and Lively South Pole expeditions 1910–13 1910–12 1910–13 Amundsen (Norway) Scott (Britain) sledge ▼ ▼ ship ▼ Source: Both maps American Geographical Society Source: Major voyages to Antarctica during the 19th century Resource D3 Voyage leader Date Nationality Ships Most southerly Achievements latitude reached Bellingshausen 1819–21 Russian Vostok and Mirnyi 69˚53’S Circumnavigated Antarctica. Discovered Peter Iøy and Alexander Island. Charted the coast round South Georgia, the South Shetland Islands and the South Sandwich Islands. Made the earliest sighting of the Antarctic continent. Dumont d’Urville 1837–40 French Astrolabe and Zeelée 66°S Discovered Terre Adélie in 1840. The expedition made extensive natural history collections. Wilkes 1838–42 United States Vincennes and Followed the edge of the East Antarctic pack ice for 2400 km, 6 other vessels confirming the existence of the Antarctic continent. Ross 1839–43 British Erebus and Terror 78°17’S Discovered the Transantarctic Mountains, Ross Ice Shelf, Ross Island and the volcanoes Erebus and Terror. The expedition made comprehensive magnetic measurements and natural history collections. -

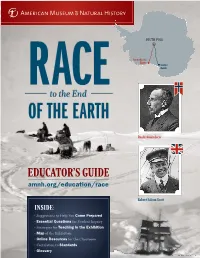

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

UK Funding and National Facilities (Research Vessel Facilities and Equipment)

UK Funding and National Facilities (Research Vessel Facilities and Equipment) Lisa McNeill and the UK community National Oceanography Centre Southampton University of Southampton Research Council Funding • Natural Environment Research Council primary funding source – Part of Research Councils UK (RCUK) – Potential to apply to other RC programmes e.g., EPSRC (e.g. for engineering related technology development) • A: Responsive mode (blue skies). Includes Urgency Funds • B: Research Themes (part of current focus – increasingly strategic, applied and impact focused). Relevant themes: – Forecasting and mitigation of natural hazards (includes “Building resilience in earthquake-prone and volcanic regions”) – Earth System Science – Sustainable Use of Natural Resources • Increasing cross Research Council themes and programmes, e.g.: – Living With Environmental Change • Impact of current economy: – Reduction of overall NERC budget in real terms – Focused on significant capital budget reduction – “Protecting front line science” through various measures including efficiency savings – External funds to support major capital investments, e.g., RRS Discovery replacement – Maintaining share of the budget for responsive mode research funding, although implementing “demand management” IODP-UKIODP • UKIODP also funded through NERC, with associated research funding • This includes funds for site survey, post-cruise and other related research International Collaboration • Many examples of co-funded research • Usage of barter/joint agreements for research -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN and KRISTIAN

… An Extraordinary Place on a Path to Prosperity Issue 73 February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN AND KRISTIAN t Helena Active Participation in Enterprise (SHAPE) aims to promote the rights and wellbeing of people with disabilities in all spheres of society and also to increase awareness. Their training programmes offer opportunities for structured work or supported employment. The focus of their service is Sto enhance employability and to support people with disabilities to achieve their maximum potential. Read the interesting stories of two SHAPE Clients, Coban and Kristian. Coban Scott-John Kristian Green y name is Coban Scott-John and I was born in Stanley on the Falkland Islands in 2001. y name is Kristian Green and I was born on At the age of two I was diagnosed in Ascension Island on 16 February 2001. At Guy’s Hospital in London, UK, as being two weeks old I was flown to the UK and Mautistic. I moved to St Helena at the age of 12 and was diagnosed in the John Radcliffe attended Prince Andrew School. I have been on holidays MHospital, Oxford, as having Down syndrome. I attended to St Helena before and always enjoy my time here. Two Boats School on Ascension until I was 16 years old. I returned to St Helena for good in January 2017. I attend SHAPE twice a week under the Carraresi programme. I am transitioning to SHAPE for when I leave I now attend Prince Andrew School which I really enjoy. I school in September this year. At SHAPE, I engage in a like reading, writing, Art, Maths, English, ICT and I love variety of activities including learning life skills and swimming. -

Download Preprint

Ross and Siegert: Lake Ellsworth englacial layers and basal melting 1 1 THIS IS AN EARTHARXIV PREPRINT OF AN ARTICLE SUBMITTED FOR 2 PUBLICATION TO THE ANNALS OF GLACIOLOGY 3 Basal melt over Subglacial Lake Ellsworth and it catchment: insights from englacial layering 1 2 4 Ross, N. , Siegert, M. , 1 5 School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, 6 UK 2 7 Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK Annals of Glaciology 61(81) 2019 2 8 Basal melting over Subglacial Lake Ellsworth and its 9 catchment: insights from englacial layering 1 2 10 Neil ROSS, Martin SIEGERT, 1 11 School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK 2 12 Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK 13 Correspondence: Neil Ross <[email protected]> 14 ABSTRACT. Deep-water ‘stable’ subglacial lakes likely contain microbial life 15 adapted in isolation to extreme environmental conditions. How water is sup- 16 plied into a subglacial lake, and how water outflows, is important for under- 17 standing these conditions. Isochronal radio-echo layers have been used to infer 18 where melting occurs above Lake Vostok and Lake Concordia in East Antarc- 19 tica but have not been used more widely. We examine englacial layers above 20 and around Lake Ellsworth, West Antarctica, to establish where the ice sheet 21 is ‘drawn down’ towards the bed and, thus, experiences melting. Layer draw- 22 down is focused over and around the NW parts of the lake as ice, flowing 23 obliquely to the lake axis, becomes afloat. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Written Evidence Submitted by the British Antarctic Survey and NERC Arctic Office (CLI0009)

Written evidence submitted by the British Antarctic Survey and NERC Arctic Office (CLI0009) Summary The Polar Regions are the regions on Earth most sensitive to climate change. What happens in the remote Polar Regions affects every person on this planet through the inter-related complexities of our global Earth system. International collaboration and environmental diplomacy enable UK polar scientists to undertake world-class research in remote and challenging polar environments on topics such as climate change, environmental management, non-native species, biosecurity, sustainable fishing and tourism. The British Antarctic Survey and the NERC Arctic Office work closely with the FCO to deliver highly significant IPCC reports on climate change in the Polar Regions, and to enable participation in the Arctic Council’s Working Groups, Expert Groups and Taskforces. The FCO Polar Regions Department works with the UK and international science community on award-winning education programmes for schools, public and international audiences. Submitted by: Professor Dame Jane Francis, Director British Antarctic Survey Henry Burgess, Head of NERC Arctic Office Linda Capper, Head of Communications, British Antarctic Survey 1. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is a Research Centre of the Natural Environment Research Council (UKRI-NERC) based in Cambridge, whose focus is science in the Polar Regions. In this role BAS works closely with the Polar Regions Department of the FCO. 2. The mission of BAS is to undertake world class science in the Polar Regions and to be the UK permanent presence in Antarctica and in South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI). This is outlined in a formal MoU between BAS, UKRI-NERC, FCO, and BEIS.