Building Technical Facility in Tuba and Euphonium Players Through the Tuba-Euphonium Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khachaturian Nocturne from the Masquerade Piano Solo Sheet Music

Khachaturian Nocturne From The Masquerade Piano Solo Sheet Music Download khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 7701 times and last read at 2021-09-27 00:51:22. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Masquerade Suite Aram Khachaturian Masquerade Suite Aram Khachaturian sheet music has been read 10264 times. Masquerade suite aram khachaturian arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 23:16:42. [ Read More ] Waltz From The Suite Masquerade By Aram Khachaturian For String Quartet Waltz From The Suite Masquerade By Aram Khachaturian For String Quartet sheet music has been read 6238 times. Waltz from the suite masquerade by aram khachaturian for string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 20:02:58. [ Read More ] A Khachaturian Waltz From The Masquerade Brass Quintet Score And Parts A Khachaturian Waltz From The Masquerade Brass Quintet Score And Parts sheet music has been read 13960 times. A khachaturian waltz from the masquerade brass quintet score and parts arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

This Masquerade for Clarinet and Piano Video Sheet Music

This Masquerade For Clarinet And Piano Video Sheet Music Download this masquerade for clarinet and piano video sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of this masquerade for clarinet and piano video sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 8548 times and last read at 2021-09-24 04:41:55. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of this masquerade for clarinet and piano video you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Clarinet, Piano Duet, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Woodwind Duet Level: Advanced [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music This Masquerade For String Quartet This Masquerade For String Quartet sheet music has been read 10725 times. This masquerade for string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 15:36:17. [ Read More ] This Masquerade For Cello And Piano With Improvisation Video This Masquerade For Cello And Piano With Improvisation Video sheet music has been read 9609 times. This masquerade for cello and piano with improvisation video arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 20:30:27. [ Read More ] This Masquerade For Viola And Piano With Improvisation Video This Masquerade For Viola And Piano With Improvisation Video sheet music has been read 9908 times. This masquerade for viola and piano with improvisation video arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 14:44:54. -

The Inception of Trumpet Performance in Brazil and Four Selected

THE INCEPTION OF TRUMPET PERFORMANCE IN BRAZIL AND FOUR SELECTED SOLOS FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO, INCLUDING MODERN PERFORMANCE EDITIONS: FANTASIA FOR TRUMPET (1854) BY HENRIQUE ALVES DE MESQUITA (1830-1906); VOCALISE-ETUDE (1929) BY HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS (1887-1959); INVOCATION AND POINT (1968) BY OSVALDO COSTA DE LACERDA (1927-2011); AND CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO (2004) BY EDMUNDO VILLANI-CÔRTES (B. 1930) A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Clayton Juliano Rodrigues Miranda In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Major Department: Music July 2016 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title THE INCEPTION OF TRUMPET PERFORMANCE IN BRAZIL AND FOUR SELECTED SOLOS FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO, INCLUDING MODERN PERFORMANCE EDITIONS: FANTASIA FOR TRUMPET (1854) BY HENRIQUE ALVES DE MESQUITA (1830-1906); VOCALISE- ETUDE (1929) BY HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS (1887-1959); INVOCATION AND POINT (1968) BY OSVALDO COSTA DE LACERDA (1927-2011); AND CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET AND PIANO (2004) BY EDMUNDO VILLANI-CÔRTES (B. 1930) By Clayton Juliano Rodrigues Miranda The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Jeremy Brekke Chair Dr. Cassie Keogh Dr. Robert W. Groves Dr. Betsy Birmingham Approved: 6/13/2016 Dr. John Miller Date Department Chair ABSTRACT This disquisition provides a modern performance edition of four Brazilian compositions for trumpet and piano by Henrique Alves de Mesquita’ (1830–1906) Fantasia para Piston [Fantasy for trumpet, 1854], Heitor Villa-Lobos’s (1887–1959) Vocalise-Estudo [Vocalise-etude, 1929], Invocação e Ponto [Invocation and point] by Osvaldo Costa de Lacerda (1927-2011), and Edmundo Villani-Cortes’s (b. -

Tutti: Circus Oz with WASO in 2006, Benjamin Northey Has Rapidly Emerged As One of the Nation’S Leading Musical Figures

PROGRAM WASO On Stage VIOLIN VIOLA OBOE TROMBONE Semra Lee-Smith Benjamin Caddy Liz Chee Joshua Davis A/Assoc Concertmaster A/Assoc Principal Viola A/Principal Oboe Chair partnered by Kierstan Arkleysmith Dr Ken Evans and Graeme Norris Dr Glenda Campbell-Evans A/Assistant Concertmaster COR ANGLAIS Nik Babic Liam O’Malley Rebecca Glorie Alison Hall Leanne Glover A/Principal 1st Violin Chair partnered by Rachael Kirk Sam & Leanne Walsh BASS TROMBONE Zak Rowntree* Allan McLean Philip Holdsworth Tutti: Circus Oz Principal 2nd Violin Elliot O’Brien CLARINET Akiko Miyazawa TUBA Helen Tuckey Allan Meyer A/Assoc Principal Cameron Brook 2nd Violin with WASO CELLO EB CLARINET Chair partnered by Sarah Blackman Catherine Cahill^ Peter & Jean Stokes Fleur Challen Louise McKay Chair partnered by TIMPANI Stephanie Dean Penrhos College BASS CLARINET Chair partnered by Marc Shigeru Komatsu Alexander Millier Alex Timcke Geary & Nadia Chiang Fri 30 November 8pm & Beth Hebert Oliver McAslan BASSOON PERCUSSION Sat 1 December 2pm Alexandra Isted Fotis Skordas Jane Kircher-Lindner Brian Maloney Chair partnered by Stott Hoare Perth Concert Hall Jane Johnston° Tim South Chair partnered by Xiao Le Wu Sue & Ron Wooller Francois Combemorel Sunmi Jung Adam Mikulicz Assoc Principal Christina DOUBLE BASS Percussion & Timpani Katsimbardis CONTRABASSOON Andrew Sinclair* HARP Ellie Lawrence Louise Elaerts Chloe Turner Melanie Pearn Sarah Bowman Andrew Tait HORN Ken Peeler Mark Tooby David Evans PIANO / CELESTE Louise Sandercock Robert Gladstones Graeme Gilling^ Jolanta Schenk FLUTE Mary-Anne Blades Principal 3rd Horn Jane Serrangeli Julia Brooke Kathryn Shinnick PICCOLO *Instruments used by these Bao Di Tang TRUMPET musicians are on loan from Michael Waye Janet Holmes à Court AC. -

PROGRAM NOTES Masterworks V: Beethoven’S Fifth Symphony

Quad City Symphony Orchestra PROGRAM NOTES Masterworks V: Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony By Jacob Bancks Associate Professor of Music Augustana College “Glowing rays shoot through the deep night… and we sense giant shadows surging to and fro, closing in on us until they destroy us… Only with this pain of love, hope, joy—which consumes but does not destroy, which would burst asunder our breasts with a mightily impassioned chord—we live on, enchanted seers of the ghostly world!” —E.T.A. Hoffman From a review of Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770- is directly traceable to Beethoven, who 1827) loaded his works with an unprecedented Twelve German Dances level of gravity. In his symphonies in partic- ular, it can be difficult to listen in any other Instrumentation: Piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clar- way than to imagine the composer in the inets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, limelight, calling all the shots and writing for percussion, and strings (no violas). posterity. It is thus important to remember Premiere: November 22, 1795. Redoutensaal, that, on several occasions, Beethoven wrote Hofburg Palace, Vienna. music intended to support other arts or so- QCSO Premiere. cial activities. It can be easy to forget that, aside from pro- This is the case with his early 12 German ducing immortal works of genius, compos- Dances, WoO 8. The “WoO” is important: it ers have occasionally proven themselves means “without opus number”; in other useful. Indeed, in many instances, the pri- words, a work that is outside of a com- mary work of a composer has been and con- poser’s essential catalogue, often un- tinues to be producing “background” music published during the composer’s lifetime. -

Cale Self, DMA

Cale Self, DMA [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Aug 2005 – May 2010 University of Georgia Athens, GA Doctor of Musical Arts • Emphasis in Euphonium Performance (minor area – conducting) • DMA Document: “Filling the Void: Examining String Literature in the Euphonium Repertoire” Aug 1996 - May 2002 West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX • Master of Arts (Instrumental Conducting) • Bachelor of Music (Music Education) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Aug 2009 – present Associate Professor of Music Assistant Director of Bands and Instructor of Tuba/Euphonium University of West Georgia Carrollton, GA • Direct all UWG athletic bands, including “The Sound That Lights the South” UWG Marching Band and the “Wolfgang” Basketball Pep Band • Assist the Director of Bands with all aspects of the UWG band program, including budget, recruiting, travel, and scheduling • Recruit and teach all euphonium and tuba majors & minors • Conduct the UWG Symphonic Band, Brass Ensemble, and Tuba Ensemble • Five years teaching Brass Methods and Applied Trombone • Two years teaching Instrumental Methods • One year as Interim Director of Bands (2010-2011) • Faculty advisor to the Lambda Eta chapter of Kappa Kappa Psi • Over 250 performances as a soloist, ensemble musician, director, or conductor • More than 75 clinics with Georgia middle and high school band programs • Eight presentations or performances at state, regional, or international conferences • Consistent service on departmental, college, and university -

Bassoon Compiled by Diana Ambache

Chamber works by women featuring the Bassoon Compiled by Diana Ambache The general format of each entry is name: title (instrumentation, publisher); date; length in minutes. Solo & Duo Susana Antón: Sonatina, c 2000, c 10’ (with piano; Collection Andrea Merenzon) Violet Archer: Sonatina, 1978. Sonata, 1980 Claude Arrieu: Rusticana (Amphion 325) c 8’. Trio en Ut (with oboe & clarinet; 1936, 9’, http://www.di-arezzo.co.uk/scores-of-Claude+Arrieu.html ). Wind Quintet (UMP) 13’, 1955 Grażyna Bacewicz: Wind Quintet (https://pwm.com.pl/en/sklep/publikacja/quintet-for-wind- instruments,grazyna-bacewicz,12273,shop.htm ) 1932, c 11’ Eve Barsham: Serenade (Emerson 498) c 5’ Elsa Barraine: Wind Quintet (di-Arezzo) 1931, c 20’ Sally Beamish: Capriccio (BDRS1) 1992, 5’ Hanna Beekhuis: Sonatina, 1948, 10’ (https://webshop.donemus.com/action/front/sheetmusic/1759 ) Di Biase: Preludio Swing (Berben Edizione Musicali 4161) Anne Boyd: Wind across Bamboo (wind quintet; http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/boyd-anne-wind-across-bamboo/3003 ) 1984, 14’. Gate of Water (flute, bass clarinet, violin, cello, piano; http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/boyd-anne-gate-of-water/22132 ) 2007, 11’. Jade Flower Song (with flute, shakuhachi & harp; AMC) 1996/2006. Hercules Close Stomp (with piano; AMC 24293) 2010 Diana Burrell: Lament (with percussion; UMP101572) 5’. (with horn, cello/drums, electric guitar/drums & piano; 1991; 10; https://ump.co.uk/catalogue/diana-burrell-barrow/ ) Mary Chandler: Divertimento (with oboe & clarinet; Phylloscopus PP68) 1967, c 10’. Masquerade (wind quintet; PP100) c 11’ Ruth Crawford Seeger: Suite No 1 (wind quintet; http://www.pytheasmusic.org/seeger_ruth_crawford.html) 1952, 10’ Jean Coulthard: Legend from the West (https://www.musiccentre.ca/node/102380 ). -

Rachmaninoff and Mozart

23 Season 2018-2019 Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Clyne Masquerade First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante Intermission Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13 I. Grave—Allegro ma non troppo II. Allegro animato III. Larghetto IV. Allegro con fuoco—Largo—Con moto This program runs approximately 2 hours. These concerts are presented in cooperation with the Sergei Rachmaninoff Foundation. The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 28 June 2015 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO INTERNATIONAL VIOLIN FESTIVAL JOSHUA BELL Sibelius Violin Concerto INTERVAL Berlioz Symphonie fantastique Pablo Heras-Casado conductor London’s Symphony Orchestra Joshua Bell violin Concert finishes approx 9.35pm The LSO International Violin Festival is generously supported by Jonathan Moulds CBE International Violin Festival Media Partner 2 Welcome 28 June 2015 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to this evening’s LSO concert. It’s a pleasure DVORA LEWIS: 37 YEARS WITH THE LSO to see Pablo Heras-Casado return to conduct this programme of Sibelius and Berlioz, following his Tonight the LSO, and many more in the world of debut performance with the Orchestra in May 2014. classical music press and public relations, salute Dvora Lewis, who celebrates her retirement after Tonight’s concert is the final instalment of the LSO 37 years at the helm of the LSO’s PR. During her time International Violin Festival, a series that has seen with the Orchestra, working through the company a line-up of outstanding soloists perform some of she set up at her office in Hampstead, Dvora has the great concertos of the repertoire, alongside attended well over 2000 LSO concerts, announced lunchtime concerts, pre-concert talks, masterclasses the arrival of four LSO Principal Conductors, and and more. For this final concert of the series we are been a true advocate for the Orchestra’s work at joined by American virtuoso Joshua Bell, who plays home and abroad. Dvora will continue to enjoy a Sibelius’ Violin Concerto. -

Modern Horn Playing in Beethoven: an Exploration of Period Appropriate Techniques for the Orchestral Music of Beethoven for the Modern Horn Player

Modern Horn Playing in Beethoven: An Exploration of Period Appropriate Techniques for the Orchestral Music of Beethoven for the Modern Horn Player Matthew John Anderson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Jeffrey Fair Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ©Copyright 2016 Matthew John Anderson I. Abstract The historically informed movement has made it increasingly apparent that orchestras can no longer interpret Beethoven, Mahler, Mozart, and Bach in exactly the same manner. It is now incumbent upon each member of the orchestra, as well as the conductor, to be aware of historic performance traditions in order to color the music with appropriate gestures. It is therefore important for horn players to explore the hand horn traditions of the baroque, classical, and early romantic periods in an effort to perform the correct inflections in a way that the composer might have expected the music to sound. As an example, in the second movement of the Beethoven’s third symphony, beginning in the second half of the eighteenth measure from the end of the movement and going into the next measure, the second horn goes from a concert middle C down a half step to a B natural. Original practice would cause the B natural to be ¾ covered which would have caused tension in the sound. Modern horns can just depress second valve to play the note giving a completely different color. The intention of this document is to inform current and future generations of hornists techniques to not only re-create sounds of the period on modern instruments, but also to create new pathways to learning repertoire through deconstructing the orchestral passages, creating new ways towards a complete understanding of the literature. -

Masquerade and Carnival: Their Customs and Costumes

1 Purchased by the Mary Stuart Book Fund Founded A.D. 1893 Cooper Union Library ]y[ASQUERADE AND (^ARNIVAL Their Custofns and Costumes. PRICE : FIFTY CENTS or TWO SHILLINGS. UE!"V"IS:H!3D j&.]Sri> EJISTL A-UG-IEIZD. PUBLISHED BY The Butterick Publishing Co. (Limited), London, and New York, 1892. — — 'Fair ladies mask'd, are roses in their bud.'' Shakespeare. 'To brisk notes in cadence beating. filance their many twinkling feet.'' Gray. "When yon do dance, I wish you A wave of the sea, that you might ever do Nothing but that." — Winter's Tale. APR 2. 1951 312213 INTR0DUeTI0N, all the collection of books and pamphlets heretofore issued upon the IN subject of Masquerades and kindred festivities, no single work has contained the condensed and general information sought by the multi- tude of inquirers who desire to render honor to Terpsichore in her fantastic moods, in the most approved manner and garb. Continuous queries from our correspondents and patrons indicated this lack, and research confirmed it. A work giving engravings and descriptions of popular costumes and naming appropriate occasions for their adoption, and also recapitulating the different varieties of Masquerade entertainments and their customs and requirements was evidently desired and needed; and to that demand we have responded in a manner that cannot fail to meet with approval and appreciation. In preparing this book every available resource has been within our reach, and the best authorities upon the subject have been consulted. These facts entitle us to the full confidence of our patrons who have only to glance over these pages to decide for themselves that the work is ample and complete, and that everyone may herein find a suitable costume for any festivity or entertainment requiring Fancy Dress, and reliable decisions as to the different codes of etiquette governing such revelries. -

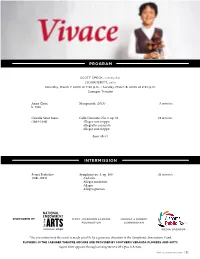

Vivace Program Pages

PROGRAM SCOTT SPECK, conductor SUJARI BRITT, cello Saturday, March 7, 2020 at 7:30 p.m. • Sunday, March 8, 2020 at 2:30 p.m. Saenger Theatre Anna Clyne Masquerade (2013)* 5 minutes b. 1980 Camille Saint Saëns Cello Concerto, No. 1, op. 33 19 minutes (1864-1949) Allegro non troppo Allegretto con moto Allegro non troppo Sujari Britt INTERMISSION Sergei Prokofiev Symphony no. 5, op. 100 46 minutes (1891-1953) Andante Allegro moderato Adagio Allegro giocoso SPONSORED BY MARY JOSEPHINE LARKINS JOANNA & ROBERT FOUNDATION CUNNINGHAM MEDIA SPONSOR *The presentation of this work is made possible by a generous donation to the Symphonic Innovations Fund. FLOWERS IN THE SAENGER THEATRE ARCADE ARE PROVIDED BY SOUTHERN VERANDA FLOWERS AND GIFTS. Sujari Britt appears through arrangement with Opus 3 Artists. MobileSymphony.org | 35 PROGRAM NOTES MASQUERADE Cellists are grateful for Saint-Saëns’ su- ance of grandeur, powerful emotions and ANNA CLYNE perb contributions to their limited rep- sparkling humor. In it Prokofiev may be BORN: London, England / March 9, 1980 ertoire: two concertos, two sonatas with heard to achieve the language – direct piano, a suite and a number of shorter and approachable yet still individual – Anna Clyne is a Grammy-nominated works. He composed Concerto No. 1 in that would satisfy both himself and the composer of acoustic and electro-acous- 1872. He dedicated it to the soloist who conservative bureaucrats who regularly tic music. Described as a “composer of played the premiere: Auguste Tolbecque, criticized his and other Soviet composers’ uncommon gifts and unusual methods” principal cellist in the Orchestra of the music.