"Marsh" of Northern Indiana and Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kankakee Watershed

Van Kankakee 8 Digit Watershed (07120001) Buren Total Acres: 1,937,043 Kankakee Watershed - 12 Digit HUCs Illinois Acres: 561,041 Indiana Acres: 1,371,490 Michigan Acres: 4,512 LAKE MICHIGAN Indiana Counties Acres s n i a Elkhart County: 7,287 o g Kane i n Fulton County: 1 i l h Berrien l c Cass Jasper County: 103,436 I i Kosciusko County: 32,683 M Lake County: D15u1P,6a3g8e LaPorte County: 298,166 Marshall County: 207,453 Newton County: 79,365 Porter County: 141,795 Pulaski County: 8,658 St. Joseph County: 175,401 Indiana 0201 Starke County: 165,607 Cook LaPorte 0202 Grey shaded 12-digit watersheds fall completely or 0207 0 2 0203 partially within Indiana. Shaded 12-digit watershed 0 St. 0403 4 0205 names and acres are on page 2. Joseph Elkhart 0208 0 0206 4-digit labels represent the last 4 numbers of the 4 0209 0406 02 12-digit watershed code. 0 0104 0 4 3 *Please note, all acres are approximate.* 1003 01 0 0302 0 0105 5 Winter 2013 1 0 10 0 0 4 6 0301 02 1 4 0 0 0 0 4 0304 0 8 7 0102 Porter 0 1 0405 1 0 Will 1004 0 1 0303 8 0 1807 0 3 0101 Lake 4 8 0702 1308 0 0309 4 1007 8 0803 8 0 0 1 0 18 0703 11 1702 0 0 3 0307 1 0 0312 3 1 1 3 0 0 0701 2 1 0 1809 0 5 1306 1302 9 0308 1 0 2 5 0 5 4 1309 6 0704 0306 1 1 8 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0310 y 0502 8 0 1703 7 3 0 0 5 0705 0504 1010 0 d 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 8 n 3 1 0506 1 1 0 u 1 3 0 0603 0505 r 0 1 4 1305 8 1806 1502 8 1 30 0 G 1 6 0503 Marshall 1 0 1311 4 1 Kosciusko 1 0904 0501 1504 1 3 0604 0602 4 1 1604 3 0807 0 3 2 1307 1 4 1 0 0 Starke 8 2 8 0 3 9 0 4 1 0 1204 1101 0 9 1805 9 0601 1602 0 1803 1205 -

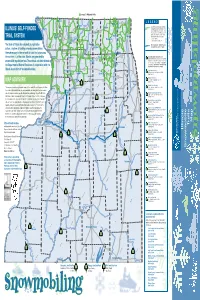

Illinois Snowmobile Trails

Connects To Wisconsin Trails East g g Dubuque g Warren L E G E N D 26 Richmond 173 78 Durand E State Grant Assisted Snowmobile Trails N Harvard O Galena O on private lands, open to the public. For B ILLINOIS’ SELF-FUNDED 75 E K detailed information on these trails, contact: A 173 L n 20 Capron n Illinois Association of Snowmobile Clubs, Inc. n P.O. Box 265 • Marseilles, IL 61341-0265 N O O P G e A McHenry Gurnee S c er B (815) 795-2021 • Fax (815) 795-6507 TRAIL SYSTEM Stockton N at iv E E onica R N H N Y e-mail: [email protected] P I R i i E W Woodstock N i T E S H website: www.ilsnowmobile.com C Freeport 20 M S S The State of Illinois has adopted, by legislative E Rockford Illinois Department of Natural Resources I 84 l V l A l D r Snowmobile Trails open to the public. e Belvidere JO v action, a system of funding whereby snowmobilers i R 90 k i i c Algonquin i themselves pay for the network of trails that criss-cross Ro 72 the northern 1/3 of the state. Monies are generated by Savanna Forreston Genoa 72 Illinois Department of Natural Resources 72 Snowmobile Trail Sites. See other side for detailed L L information on these trails. An advance call to the site 64 O Monroe snowmobile registration fees. These funds are administered by R 26 R E A L is recommended for trail conditions and suitability for C G O Center Elgin b b the Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with the snowmobile use. -

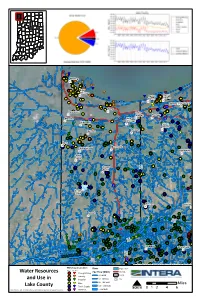

Water Resources and Use in Lake County

¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ " ¸ S # Whiting # ¸ ¸ # # " ¸ S S" # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # East ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ Chicago # ¸ ¸ # S" # Ogden Burns Harbor ¸ # Dunes ¸ # ¸ # S" ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ S" # ¸ # Porter Chesterton ¸ I-90 # S" ¸ ¸ # ¸ # # ¸ ¨¦§ I-94 S" # Gary ¨¦§ Hammond S" Lake S" Station Portage 80 ¸ # New I- ¸ S" Munster # S" I-80 § ¸ ¸ ¨¦ ¸ # # # ¸ ¨¦§ Chicago # " ¸ S ¸ # # Highland ¸ # ¸ S" S" # South ¸ # Haven ¸ # ¸ # Hobart ¸ " # Griffith S ¸ # S" ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # " # S ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # # ¸ Dyer # ¸ ¸ # S" Merrillville # ¸ Schererville # " S" Valparaiso S S" Saint John S" r e e ¸ t # ¸ k # r ¸ # a o ¸ Crown # L P ¸ # Point ¸ S" # ¸ # ¸ # ¨¦§ I - ¸ 6 # Cedar 5 Lake ¸ # ¸ Cedar S" # ¸ Lake # ¸ Hebron Kouts # S" S" ¸ Lowell # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ S" # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ Por # t ¸ ¸ e # # r ¸ ¸ # ¸ # Jas # ¸ p # ¸ e # r ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ # ke # ¸ # a ¸ ¸ ¸ L # # # ¸ # ¸ r # e sp ¸ a # J ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ DeMotte # Wheatfield ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ " # n S r ¸ # S" e o ¸ ¸ # # ¸ t # p s w ¸ ¸ # # a e ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # J N r ¸ Rive # ¸ Kankakee # ¨¦§I ¸ # - Lake 6 5 ewton N ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # Withdrawal -

(11Gr100), a Historic Native American Short Duration Occupation on the Des Plaines River, Grundy County, Illinois

The Highlands Site Craig and Vorreyer, 2004 Mundane Place or Sacred Space: Interpreting the Highlands Site (11Gr100), a Historic Native American Short Duration Occupation on the Des Plaines River, Grundy County, Illinois By Joseph Craig and Susan Vorreyer (Environmental Compliance Consultants, Inc.) Archaeological excavations conducted at the Highlands Site near Channahon, Illinois exposed a small, short-duration historic period Native American occupation situated on the upland bluff overlooking the Des Plaines River. Excavated features included four shallow basins, one hearth and a unique semi-circular shallow depression. Historic period artifacts were sparse and included glass seed beads, pieces of scrap copper and lead, and triangular projectile points. Rich amounts of subsistence remains including elk and bison were also recovered from several features. The Highlands site is interpreted as representing a Potawatomi occupation dating to the late 18 th or early 19 th century. Using historical accounts and illustrations of Potawatomi sites and religious customs and activities, the Highlands Site appears to represent a Potawatomi ritual location. Although graves or human skeletal material were not encountered, the analyses of the artifact assemblage, feature morphology and patterning, and interpretation of the faunal assemblage suggests the Highlands site was utilized as a mortuary location. The area surrounding the base of Lake Michigan at the point where the Kankakee and Des Plaines rivers merge with the upper reaches of the Illinois River was the penetration point of the Potawatomi migration into the western Great Lakes region known as the Illinois Country. Beginning in the mid-1600s, the Potawatomi, who inhabited the western Michigan, initiated a series of westward movements to acquire larger hunting territories buttressing their participation in the North American fur trade and also to avoid pressure (and competition) from Iroquois raiders and trappers. -

Chief Shabbona History

CHIEF SHABBONA HISTORY It was in 1775, one year before the American Revolution Shab-eh-nay was interested in the welfare of both Indians and settlers. The newcomers that an Indian boy was born near the banks of the taught him how to grow better crops and Shab-eh-nay shared his knowledge of nature – Kankakee River. A boy who would grow up to befriend the especially the medicinal powers of plants. new nation’s people. His Ottawa parents named him In 1827, the Winnebago planned an attack on the frontier village of Chicago; Shab-eh-nay “Shab-eh-nay” (Shabbona), which means “Built like a rode to Fort Chicago to warn the white men. In 1832, he made a heroic ride when Bear”. And true to his name, he grew up to be a muscular Blackhawk planned a raid to reclaim Indian land. The 54 year old Potawatomi Chief rode 200 lbs., standing 5’ 9” tall. 48 hours to warn settlers through unmapped forest and vast prairies to prevent Around 1800, Shab-eh-nay was part of an Ottawa hunting bloodshed of both settlers and Indians. party that wandered into a Potawatomi camp near the In gratitude for his peacemaking efforts, the United States, in Article III of the 1829 Treaty southern shore of Lake Michigan. All of the Ottawa of Prairie du Chien, reserved 1,280 acres of land for Chief Shab-eh-nay and his Band. returned to their own village, except Shab-eh-nay, who These lands were historically occupied by the Potawatomi in what is now DeKalb County, stayed through the winter. -

The North Americanwaterfowl M Anagement P Lan the North

PROJECT.HTML 219.980.5455 (h) room for room WWW.EARTH-SEA.COM/ 219.945.0543 (w) 13 219.924.4403—ext. (w) always or visit or Project Manager Project Chairman BOB NICKOVICH, BOB BLYTHE, DICK There is There For further information please contact: please information further For There is always room for more, and there is much left to do. We welcome your inquiries into participation as a partner. a as participation into inquiries your welcome We do. to left much is there and more, for room always is There courtesy of USDA NRCS. USDA of courtesy Several pictures in this publication this in pictures Several Lake Heritage Parks Foundation Parks Heritage Lake Lake County Parks Dept. Parks County Lake WYIN-TV Lake County Fish and Game and Fish County Lake Wille & Stiener Real Estate Real Stiener & Wille Kankakee River Basin Commission Basin River Kankakee Waterfowl USA Waterfowl J.F. New & Associates & New J.F. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife and Fish U.S. Indiana Heritage Trust Fund Trust Heritage Indiana Service Indiana Department of Natural Resources Natural of Department Indiana USDA Natural Resources Conservation Resources Natural USDA Inc. University of Notre Dame Notre of University Griffith Izaak Walton Conservation Lands, Conservation Walton Izaak Griffith Town of Demotte of Town GMC Dealers of NW Indiana NW of Dealers GMC The Nature Conservancy Nature The Enbridge Pipelines (Lakehead) LLC (Lakehead) Pipelines Enbridge Studer & Associates & Studer Dunes Calumet Audubon Society Audubon Calumet Dunes St. Joseph County Parks Department Parks County Joseph St. Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Unlimited, Ducks Ritschard Bros., Inc. -

Floods of October 1954 in the Chicago Area, Illinois and Indiana

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OP THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 PREFACE This preliminary report on the floods of October 1954 in the Chicago area of Illinois and Indiana was prepared by the Water Resources Division, C. G. Paulsen, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch. Basic records of discharge in the area covered by this report were collected in cooperation with the Illinois De partment of Public Works and Buildings, Division of Waterways; the Indiana Flood Control and Water Resources Commission; and the Indiana Department of Conservation, Division of Water Re sources. The records of discharge were collected and computed under the direction of J. H. Morgan, district engineer, Champaign, 111.; and D. M. Corbett, district engineer, Indi anapolis, Ind. The data were computed and te^t prepared by the authors in the district offices in Illinois and Indiana. The report was assembled by the staff of the Technical Stand ards Section in Washington, D. C., Tate Dalrymple, chief. li CONTENTS Page Introduction............................................. 1 General description of floods............................ 1 Location.............................................. 1 Little Calumet River basin........................... -

Indiana Grand Kankakee Marsh Restoration Project

Indiana Grand Kankakee Marsh Restoration Project www.igkmrp.org The Grand Kankakee Marsh was one of the premier wetland ecosystems in North America with nearly 1 million acres along the Kankakee River including emergent marsh, wet prairie, sedge meadow, shrub-scrub, and floodplain forest communities interspersed with black oak savanna and upland prairie. From its source near South Bend to the Illinois state line, the Kankakee River meandered some 250 miles through 2,000 bends, with an average fall of only 5 inches per mile. The marsh was legendary for the wide variety of plant and animal species that attracted sport and market hunters from around the world. Accounts from the late 1800’s describe barrels of frog legs, wagonloads of pelts, and railroad cars of game bound for the Chicago markets while European as well as American sportsmen relished the particularly abundant waterfowl and other wetland game birds. By the early 20th century efforts to drain the marsh for agriculture use had deepened and channelized the river and reduced its length in Indiana to less than 85 miles. For the most part the conversion of the landscape to intensive row crop production remains to the present time in spite of freQuent flooding. Attempts to bring back portions of the marsh in some of the wetter, more difficult to farm areas had little success before formation of the IGKMRP. The project launched in 1994 to pursue funding under the federal North American Wetland Conservation Act. The initial grant application for $1.5 million had 16 diverse partners that brought $2.4 million of matching funds for the goal of linking a network of 26,500 acres protected acres of wetlands for wildlife. -

Geology of the Kankakee River System in Kankakee County, Illinois

s »f OS: CO- GEOLOGY OF THE KANKAKEE RIVER SYSTEM IN KANKAKEE COUNTY, ILLINOIS David L Gross and Richard C. Berg Illinois Institute of Natural Resources STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY NOTES 92 Jack A. Simon, Chief January 1981 COVER PHOTO: Vertical aerial photograph of the Kankakee River at the Illinois- Indiana state line. Gross, David L. Geology of the Kankakee River system in Kankakee County, Illinois / by David L. Gross and Richard C. Berg.— Champaign, 111. : Illinois State Geological Survey, January 1981. 80 p. : ill. : 28 cm. — (Environmental geology note ; 92) References : p. 75. 1. Geology— Illinois— Kankakee County 2. Geology— Illinois— Kankakee River. I. Berg, Richard C. II. Series. Printed by authority of the State of Illinois/1981/2000. GEOLOGY OF THE KANKAKEE RIVER SYSTEM IN KANKAKEE COUNTY, ILLINOIS David L Gross and Richard C. Berg ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Natural Resources Building 615 East Peabody Drive ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY NOTES 92 Champaign, IL 61820 January 1981 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/geologyofkankake92gros CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 The river system 1 Goals of project 4 Previous studies 4 Methods 6 GENERAL GEOLOGY 18 Geologic History 18 Surficial geology along river 20 Bedrock topography and sand thickness along river 26 GEOLOGY OF SEDIMENT IN RIVER 39 Thickness and distribution 39 Chemical composition 55 Discussion of sedimentation 61 RIVER MORPHOLOGY 64 Air photo evidence, 1939-1954 65 Air photo evidence, 1954-1973 68 Topographic map evidence, 1922-1973 71 SUMMARY 72 Acknowledgments 73 REFERENCES 75 APPENDIX 77 m TABLES 1. -

Water Resource Availability in the Kankakee River Basin, Indiana: Division of Water, Water Resources, Assessment 90-3

WATER RESOURCE AVAILABILITY IN THE KANKAKEE RIVER BASIN, DIVISION OF WATER published 1990 INDIANA - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Figure 1. Location of the Kankakee River Basin In response to legislative directives contained in the 1983 Water Resource Management Act, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Water published a report describing the availability, distribution, quality, and use of surface water and ground water in the Kankakee River Basin, Indiana.* The third in a series of 12 regional watershed assess- ments, the report provides hydrologic data and related information for persons interested in the basin’s water resource. The following is a summary of that report. The full report can be obtained from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Water. For ordering information, please see the instructions printed at the end of this summary. The Kankakee River Basin drains 2989 sq. mi. (square miles) in northwest Indiana, 2169 sq. mi. in northeast Illinois, and about 7 sq. mi. in southwest Lower Michigan (figure 1). The Kankakee River heads near South Bend, Indiana, then flows westward into Illinois, where it joins with the Des Plaines River to form the Illinois River. The area of Lake County which originally drained to Lake Michigan but now drains by means of artificial diversion to the Illinois River is not considered to be part of the Kankakee River Basin study region. Although the Kankakee River basin includes portions of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan, the discussion below will focus on the Indiana portion of the basin. SOCIOECONOMIC SETTING Thirteen Indiana counties lie completely or partially within the Kankakee River Basin, but nine counties consti- tute more than 90 percent of the basin’s land area in Indiana. -

2017 State of Illinois Department of Natural Resources Illinois Fishing Information Effective: April 1, 2017 Through March 31, 2018

2017 State of Illinois Department of Natural Resources Illinois Fishing Information Effective: April 1, 2017 through March 31, 2018 Wayne Herndon, veteran IDNR Fisheries Biologist, 45 years of service to the anglers of Illinois IDNR Division of Fisheries Division of Fisheries www.dnr.illinois.gov www.ifishillinois.org Building the Future of Fishing in Illinois FC1 Message from the Director Thank you for picking up a copy of the 2017 Illinois Fishing Information guide. The booklet is packed with useful information on places to fish and rules to follow when fishing in Illinois. In the pages that follow, those who enjoy fishing will find an updated summary of statewide fishing regulations in Illinois, as well as details on site-specific regulations that are organized by the body of water or water area at which those regulations apply. Once again for 2017, Illinois Free Fishing Days will be during the Father’s Day weekend in June – with the dates of Friday, June 16 through Monday, June 19. Free Fishing Days provide an opportunity for novice anglers and families to go fishing even if they have not yet purchased a fishing license. While we update the Illinois Fishing Information guide each year, some site-specific regulations may be changed in emergency situations through the administrative rule process. In those cases, the emergency changes to regulations will be posted at the location where the rules apply. We also post changes in rules online at www.ifishillinois.org. Illinois anglers are guardians of our state’s aquatic resources. The money you spend on fishing licenses and equipment helps fund our fishery programs, and helps ensure the future of fishing in Illinois. -

1. Hello, My Name Is Dr. Jim Paul. John Was So Debonair in His Suit

Local History 101: Making Life-Changing Decisions in the Kankakee River Valley Episode 1: Potawatomi Peril (to 1838) Dr. James Paul’s Narrative with Slides 1. Hello, my name is Dr. Jim Paul. John was so debonair in his suit and derby hat as he, and other Bourbonnais Grove Historical Society members who wore 19th century clothing, greeted guests to the gardens of the Letourneau Home/Museum. It was late June 2013, and the event was “Remembering Bourbonnais Grove: 1832-75” on the Sunday ending the Bourbonnais Friendship Festival. We were photographed after my portrayal of George Letourneau and no longer wearing my fake beard. John grew up near Kankakee River State Park. As a boy, he explored the former Potawatomi village nearby. He was impressed with their local contributions and burial mound. He studied Potawatomi history throughout his life. John and I planned to team teach this course, but now I will present it by myself as tribute to him. There are two parts to this course presentation: 1) the Potawatomi conflict and crises to 1838, and 2) the Potawatomi interaction with Noel LeVasseur. 1 2. The first part of this course presentation, to slide 55, is based on John’s fall 2019 Lifelong Learning Institute course entitled “Potawatomi Flashback—A Life Long Leaner’s View”. Since he and I had team taught several travelogues for the Lifelong Learning Institute, we decided to team teach this history course by combining his Potawatomi narrative with my insights into Noel LeVasseur’s life with the Potawatomi. We considered this course to be the first in a series of courses entitled Local History 101: Making Life-Changing Decisions in the Kankakee River Valley.