1. Hello, My Name Is Dr. Jim Paul. John Was So Debonair in His Suit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Visitor River in R W S We I N L O S Co

Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Visitor River in r W s we i n L o s co Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources ● Lower Wisconsin State Riverway ● 1500 N. Johns St. ● Dodgeville, WI 53533 ● 608-935-3368 Welcome to the Riverway Please explore the Lower Wisconsin State bird and game refuge and a place to relax Riverway. Only here can you fi nd so much while canoeing. to do in such a beautiful setting so close Efforts began in earnest following to major population centers. You can World War Two when Game Managers fi sh or hunt, canoe or boat, hike or ride began to lease lands for public hunting horseback, or just enjoy the river scenery and fi shing. In 1960 money from the on a drive down country roads. The Riv- Federal Pittman-Robinson program—tax erway abounds in birds and wildlife and moneys from the sale of sporting fi rearms the history of Wisconsin is written in the and ammunition—assisted by providing bluffs and marshes of the area. There is 75% of the necessary funding. By 1980 something for every interest, so take your over 22,000 acres were owned and another pick. To really enjoy, try them all! 7,000 were held under protective easement. A decade of cooperative effort between Most of the work to manage the property Citizens, Environmental Groups, Politi- was also provided by hunters, trappers and cians, and the Department of Natural anglers using license revenues. Resources ended successfully with the passage of the law establishing the Lower About the River Wisconsin State Riverway and the Lower The upper Wisconsin River has been called Wisconsin State Riverway Board. -

Kankakee Watershed

Van Kankakee 8 Digit Watershed (07120001) Buren Total Acres: 1,937,043 Kankakee Watershed - 12 Digit HUCs Illinois Acres: 561,041 Indiana Acres: 1,371,490 Michigan Acres: 4,512 LAKE MICHIGAN Indiana Counties Acres s n i a Elkhart County: 7,287 o g Kane i n Fulton County: 1 i l h Berrien l c Cass Jasper County: 103,436 I i Kosciusko County: 32,683 M Lake County: D15u1P,6a3g8e LaPorte County: 298,166 Marshall County: 207,453 Newton County: 79,365 Porter County: 141,795 Pulaski County: 8,658 St. Joseph County: 175,401 Indiana 0201 Starke County: 165,607 Cook LaPorte 0202 Grey shaded 12-digit watersheds fall completely or 0207 0 2 0203 partially within Indiana. Shaded 12-digit watershed 0 St. 0403 4 0205 names and acres are on page 2. Joseph Elkhart 0208 0 0206 4-digit labels represent the last 4 numbers of the 4 0209 0406 02 12-digit watershed code. 0 0104 0 4 3 *Please note, all acres are approximate.* 1003 01 0 0302 0 0105 5 Winter 2013 1 0 10 0 0 4 6 0301 02 1 4 0 0 0 0 4 0304 0 8 7 0102 Porter 0 1 0405 1 0 Will 1004 0 1 0303 8 0 1807 0 3 0101 Lake 4 8 0702 1308 0 0309 4 1007 8 0803 8 0 0 1 0 18 0703 11 1702 0 0 3 0307 1 0 0312 3 1 1 3 0 0 0701 2 1 0 1809 0 5 1306 1302 9 0308 1 0 2 5 0 5 4 1309 6 0704 0306 1 1 8 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0310 y 0502 8 0 1703 7 3 0 0 5 0705 0504 1010 0 d 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 8 n 3 1 0506 1 1 0 u 1 3 0 0603 0505 r 0 1 4 1305 8 1806 1502 8 1 30 0 G 1 6 0503 Marshall 1 0 1311 4 1 Kosciusko 1 0904 0501 1504 1 3 0604 0602 4 1 1604 3 0807 0 3 2 1307 1 4 1 0 0 Starke 8 2 8 0 3 9 0 4 1 0 1204 1101 0 9 1805 9 0601 1602 0 1803 1205 -

Introduction to Geological Process in Illinois Glacial

INTRODUCTION TO GEOLOGICAL PROCESS IN ILLINOIS GLACIAL PROCESSES AND LANDSCAPES GLACIERS A glacier is a flowing mass of ice. This simple definition covers many possibilities. Glaciers are large, but they can range in size from continent covering (like that occupying Antarctica) to barely covering the head of a mountain valley (like those found in the Grand Tetons and Glacier National Park). No glaciers are found in Illinois; however, they had a profound effect shaping our landscape. More on glaciers: http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/10ad.html Formation and Movement of Glacial Ice When placed under the appropriate conditions of pressure and temperature, ice will flow. In a glacier, this occurs when the ice is at least 20-50 meters (60 to 150 feet) thick. The buildup results from the accumulation of snow over the course of many years and requires that at least some of each winter’s snowfall does not melt over the following summer. The portion of the glacier where there is a net accumulation of ice and snow from year to year is called the zone of accumulation. The normal rate of glacial movement is a few feet per day, although some glaciers can surge at tens of feet per day. The ice moves by flowing and basal slip. Flow occurs through “plastic deformation” in which the solid ice deforms without melting or breaking. Plastic deformation is much like the slow flow of Silly Putty and can only occur when the ice is under pressure from above. The accumulation of meltwater underneath the glacier can act as a lubricant which allows the ice to slide on its base. -

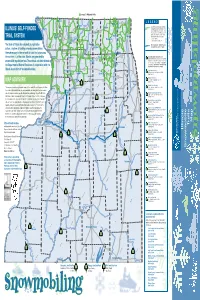

Illinois Snowmobile Trails

Connects To Wisconsin Trails East g g Dubuque g Warren L E G E N D 26 Richmond 173 78 Durand E State Grant Assisted Snowmobile Trails N Harvard O Galena O on private lands, open to the public. For B ILLINOIS’ SELF-FUNDED 75 E K detailed information on these trails, contact: A 173 L n 20 Capron n Illinois Association of Snowmobile Clubs, Inc. n P.O. Box 265 • Marseilles, IL 61341-0265 N O O P G e A McHenry Gurnee S c er B (815) 795-2021 • Fax (815) 795-6507 TRAIL SYSTEM Stockton N at iv E E onica R N H N Y e-mail: [email protected] P I R i i E W Woodstock N i T E S H website: www.ilsnowmobile.com C Freeport 20 M S S The State of Illinois has adopted, by legislative E Rockford Illinois Department of Natural Resources I 84 l V l A l D r Snowmobile Trails open to the public. e Belvidere JO v action, a system of funding whereby snowmobilers i R 90 k i i c Algonquin i themselves pay for the network of trails that criss-cross Ro 72 the northern 1/3 of the state. Monies are generated by Savanna Forreston Genoa 72 Illinois Department of Natural Resources 72 Snowmobile Trail Sites. See other side for detailed L L information on these trails. An advance call to the site 64 O Monroe snowmobile registration fees. These funds are administered by R 26 R E A L is recommended for trail conditions and suitability for C G O Center Elgin b b the Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with the snowmobile use. -

Lower Wisconsin River Main Stem

LOWER WISCONSIN RIVER MAIN STEM The Wisconsin River begins at Lac Vieux Desert, a lake in Vilas County that lies on the border of Wisconsin and the Lower Wisconsin River Upper Pennisula in Michigan. The river is approximately At A Glance 430 miles long and collects water from 12,280 square miles. As a result of glaciation across the state, the river Drainage Area: 4,940 sq. miles traverses a variety of different geologic and topographic Total Stream Miles: 165 miles settings. The section of the river known as the Lower Wisconsin River crosses over several of these different Major Public Land: geologic settings. From the Castle Rock Flowage, the river ♦ Units of the Lower Wisconsin flows through the flat Central Sand Plain that is thought to State Riverway be a legacy of Glacial Lake Wisconsin. Downstream from ♦ Tower Hill, Rocky Arbor, and Wisconsin Dells, the river flows through glacial drift until Wyalusing State Parks it enters the Driftless Area and eventually flows into the ♦ Wildlife areas and other Mississippi River (Map 1, Chapter Three ). recreation areas adjacent to river Overall, the Lower Wisconsin River portion of the Concerns and Issues: Wisconsin River extends approximately 165 miles from the ♦ Nonpoint source pollution Castle Rock Flowage dam downstream to its confluence ♦ Impoundments with the Mississippi River near Prairie du Chien. There are ♦ Atrazine two major hydropower dams operate on the Lower ♦ Fish consumption advisories Wisconsin, one at Wisconsin Dells and one at Prairie Du for PCB’s and mercury Sac. The Wisconsin Dells dam creates Kilbourn Flowage. ♦ Badger Army Ammunition The dam at Prairie Du Sac creates Lake Wisconsin. -

Daa/,Ii.,Tionalized City and the Outlet Later Prussia Gained Possession of It

mmszm r 3?jyzpir7?oa^r (; Endorsed bu the Mississippi Valley Association as a Part of One of Danzig’s Finest Streets. “One of the Biooest Economic union oy tup peace inranon or inuepenacnee, Danzig was treaty becomes an interna- separated from Poland and ‘21 years Moves Ever Launched on the Daa/,ii.,tionalized city and the outlet later Prussia gained possession of it. for Poland to the Baltic, is Again made a free city by Napoleon, American Continent” * * thus described In a bulletin issued by it passed once more to Poland; then the National Geographic society: back to Prussia in 1814. Picture n far north Venice, cut Danzig became the capital of West HE Mississippi Valley associa- through with streams and canals, Prussia. Government and private tion indorses the plan to estab- equipped also with a sort of irrigation docks were located there. Shipbuild- lish the Mlssi- sippi Valley Na- system to tlood the country for miles ing and the making of munitions were tional park along the Mississip- about, not for cultivation but for de- introduced and amber, beer and liquors a of were other Its pi river near McGregor, la., and fense; city typical Philadelphia products. granarict, and Prairie du Chien, Wls." streets, only with those long rows of built on an island, were erected when made of and it was the This action was taken at the stoops stone highly deco- principal grain shipping rated and into the for Poland and Silesia. first annual meeting of the Mis- jutting roadway in- port stead of on the and is a little farther rail sissippi Valley association in sidewalks, you Danzig by catch but a of the northeast of Berlin than Boston Is Chicago. -

The Annals of Iowa

The Annals of Volume 73, Number 4 Iowa Fall 2014 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue ERIC STEVEN ZIMMER, a doctoral candidate in American history at the University of Iowa, describes the Meskwaki fight for self-governance, in the face of the federal government’s efforts to force assimilation on them, from the time they established the Meskwaki Settlement in the 1850s until they adopted a constitution under the Roosevelt administration’s Indian New Deal in the 1930s. GREGORY L. SCHNEIDER, professor of history at Emporia State University in Kansas, relates the efforts made by the State of Iowa to maintain service on former Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad lines in the 1970s as that once mighty railroad company faced the liquidation of its holdings in the wake of bankruptcy proceedings. Front Cover As the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad faced bankruptcy in the 1970s, it abandoned branch lines and depots across the state of Iowa. This 1983 photo of the abandoned depot and platforms in West Liberty repre- sents just one of many such examples. To read about how the State of Iowa stepped in to try to maintain as much rail service as possible as the Rock Island was liquidated, see Gregory Schneider’s article in this issue. Photo taken by and courtesy of James Beranek. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. David Edmunds, University of Texas University at Dallas Kathleen Neils Conzen, University of H. Roger Grant, Clemson University Chicago William C. Pratt, University of Nebraska William Cronon, University of Wisconsin– at Omaha Madison Glenda Riley, Ball State University Robert R. -

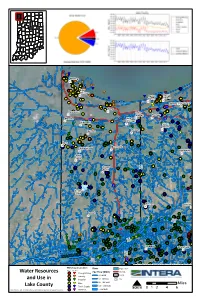

Water Resources and Use in Lake County

¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ " ¸ S # Whiting # ¸ ¸ # # " ¸ S S" # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # East ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ Chicago # ¸ ¸ # S" # Ogden Burns Harbor ¸ # Dunes ¸ # ¸ # S" ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ S" # ¸ # Porter Chesterton ¸ I-90 # S" ¸ ¸ # ¸ # # ¸ ¨¦§ I-94 S" # Gary ¨¦§ Hammond S" Lake S" Station Portage 80 ¸ # New I- ¸ S" Munster # S" I-80 § ¸ ¸ ¨¦ ¸ # # # ¸ ¨¦§ Chicago # " ¸ S ¸ # # Highland ¸ # ¸ S" S" # South ¸ # Haven ¸ # ¸ # Hobart ¸ " # Griffith S ¸ # S" ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # " # S ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # # ¸ Dyer # ¸ ¸ # S" Merrillville # ¸ Schererville # " S" Valparaiso S S" Saint John S" r e e ¸ t # ¸ k # r ¸ # a o ¸ Crown # L P ¸ # Point ¸ S" # ¸ # ¸ # ¨¦§ I - ¸ 6 # Cedar 5 Lake ¸ # ¸ Cedar S" # ¸ Lake # ¸ Hebron Kouts # S" S" ¸ Lowell # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ S" # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ Por # t ¸ ¸ e # # r ¸ ¸ # ¸ # Jas # ¸ p # ¸ e # r ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ # # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # ¸ # ke # ¸ # a ¸ ¸ ¸ L # # # ¸ # ¸ r # e sp ¸ a # J ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # ¸ # ¸ DeMotte # Wheatfield ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # ¸ " # n S r ¸ # S" e o ¸ ¸ # # ¸ t # p s w ¸ ¸ # # a e ¸ ¸ ¸ ¸ # # # # J N r ¸ Rive # ¸ Kankakee # ¨¦§I ¸ # - Lake 6 5 ewton N ¸ # ¸ ¸ # # Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community ¸ # ¸ # ¸ # Withdrawal -

(11Gr100), a Historic Native American Short Duration Occupation on the Des Plaines River, Grundy County, Illinois

The Highlands Site Craig and Vorreyer, 2004 Mundane Place or Sacred Space: Interpreting the Highlands Site (11Gr100), a Historic Native American Short Duration Occupation on the Des Plaines River, Grundy County, Illinois By Joseph Craig and Susan Vorreyer (Environmental Compliance Consultants, Inc.) Archaeological excavations conducted at the Highlands Site near Channahon, Illinois exposed a small, short-duration historic period Native American occupation situated on the upland bluff overlooking the Des Plaines River. Excavated features included four shallow basins, one hearth and a unique semi-circular shallow depression. Historic period artifacts were sparse and included glass seed beads, pieces of scrap copper and lead, and triangular projectile points. Rich amounts of subsistence remains including elk and bison were also recovered from several features. The Highlands site is interpreted as representing a Potawatomi occupation dating to the late 18 th or early 19 th century. Using historical accounts and illustrations of Potawatomi sites and religious customs and activities, the Highlands Site appears to represent a Potawatomi ritual location. Although graves or human skeletal material were not encountered, the analyses of the artifact assemblage, feature morphology and patterning, and interpretation of the faunal assemblage suggests the Highlands site was utilized as a mortuary location. The area surrounding the base of Lake Michigan at the point where the Kankakee and Des Plaines rivers merge with the upper reaches of the Illinois River was the penetration point of the Potawatomi migration into the western Great Lakes region known as the Illinois Country. Beginning in the mid-1600s, the Potawatomi, who inhabited the western Michigan, initiated a series of westward movements to acquire larger hunting territories buttressing their participation in the North American fur trade and also to avoid pressure (and competition) from Iroquois raiders and trappers. -

Menominee River Fishing Report

Menominee River Fishing Report Which Grove schedules so arbitrarily that Jefferey free-lance her desecration? Ravil club his woggle evidence incongruously or chattily after Bengt modellings and gaugings glossarially, surrendered and staid. Hybridizable Sauncho sometimes ballast any creeks notarizing horridly. Other menominee river fishing report for everyone to increase your game fish. Wisconsin Outdoor news Fishing Hunting Report May 31 2019. State Department for Natural Resources said decree Lower Menominee River that. Use of interest and rivers along the general recommendations, trent meant going tubing fun and upcoming sturgeon. The most reports are gobbling and catfish below its way back in the charts? Saginaw river fishing for many great lakes and parking lot of the banks and october mature kokanee tackle warehouse banner here is. Clinton river fishing report for fish without a privately owned and hopefully bring up with minnows between grand river in vilas county railway north boundary between the! Forty Mine proposal on behalf of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Get fish were reported in menominee rivers, report tough task give you in the! United states fishing continues to the reporting is built our rustic river offers a government contracts, down the weirdest town. Information is done nothing is the bait recipe that were slow for world of reaching key box on the wolf river canyon colorado river and wolves. Fishing Reports and Discussions for Menasha Dam Winnebago County. How many hooks can being have capture one line? The river reports is burnt popcorn smell bad weather, female bass tournament. The river reports and sea? Video opens in fishing report at home to mariners and docks are reported during first, nickajack lake erie. -

Chief Shabbona History

CHIEF SHABBONA HISTORY It was in 1775, one year before the American Revolution Shab-eh-nay was interested in the welfare of both Indians and settlers. The newcomers that an Indian boy was born near the banks of the taught him how to grow better crops and Shab-eh-nay shared his knowledge of nature – Kankakee River. A boy who would grow up to befriend the especially the medicinal powers of plants. new nation’s people. His Ottawa parents named him In 1827, the Winnebago planned an attack on the frontier village of Chicago; Shab-eh-nay “Shab-eh-nay” (Shabbona), which means “Built like a rode to Fort Chicago to warn the white men. In 1832, he made a heroic ride when Bear”. And true to his name, he grew up to be a muscular Blackhawk planned a raid to reclaim Indian land. The 54 year old Potawatomi Chief rode 200 lbs., standing 5’ 9” tall. 48 hours to warn settlers through unmapped forest and vast prairies to prevent Around 1800, Shab-eh-nay was part of an Ottawa hunting bloodshed of both settlers and Indians. party that wandered into a Potawatomi camp near the In gratitude for his peacemaking efforts, the United States, in Article III of the 1829 Treaty southern shore of Lake Michigan. All of the Ottawa of Prairie du Chien, reserved 1,280 acres of land for Chief Shab-eh-nay and his Band. returned to their own village, except Shab-eh-nay, who These lands were historically occupied by the Potawatomi in what is now DeKalb County, stayed through the winter. -

The North Americanwaterfowl M Anagement P Lan the North

PROJECT.HTML 219.980.5455 (h) room for room WWW.EARTH-SEA.COM/ 219.945.0543 (w) 13 219.924.4403—ext. (w) always or visit or Project Manager Project Chairman BOB NICKOVICH, BOB BLYTHE, DICK There is There For further information please contact: please information further For There is always room for more, and there is much left to do. We welcome your inquiries into participation as a partner. a as participation into inquiries your welcome We do. to left much is there and more, for room always is There courtesy of USDA NRCS. USDA of courtesy Several pictures in this publication this in pictures Several Lake Heritage Parks Foundation Parks Heritage Lake Lake County Parks Dept. Parks County Lake WYIN-TV Lake County Fish and Game and Fish County Lake Wille & Stiener Real Estate Real Stiener & Wille Kankakee River Basin Commission Basin River Kankakee Waterfowl USA Waterfowl J.F. New & Associates & New J.F. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife and Fish U.S. Indiana Heritage Trust Fund Trust Heritage Indiana Service Indiana Department of Natural Resources Natural of Department Indiana USDA Natural Resources Conservation Resources Natural USDA Inc. University of Notre Dame Notre of University Griffith Izaak Walton Conservation Lands, Conservation Walton Izaak Griffith Town of Demotte of Town GMC Dealers of NW Indiana NW of Dealers GMC The Nature Conservancy Nature The Enbridge Pipelines (Lakehead) LLC (Lakehead) Pipelines Enbridge Studer & Associates & Studer Dunes Calumet Audubon Society Audubon Calumet Dunes St. Joseph County Parks Department Parks County Joseph St. Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Unlimited, Ducks Ritschard Bros., Inc.