Dance Photographs Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dance “Festival Within a Festival” at the Fringe

A dance “festival within a festival” at The Fringe www.bookingdance.com SEE 7 DYNAMIC DANCE COMPANIES FROM AMERICA IN ONE SHOW WED, AUG 12 - SUN, AUG 16 Cover and inside cover photo:Lois Greenfield WORLD PREMIERES ABOUT BOOKING DANCE FESTIVALS ALL COMPANIES DEBUTING IN EDINBURGH FOR THE FIRST TIME The Booking DANCE FESTIVAL is the brainchild of Producer Jodi Kaplan, born with the intention of creating a cultural exchange between performing artists and international communities. The Festival occurs Welcome! annually at different locations around the globe, continually bridging dance artists and audiences worldwide. It is the long-term vision of Booking DANCE FESTIVAL to return annually to the Edinburgh Fringe for a full Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Edinburgh 2009 is the first dance “festival within a festival” three week run while additionally producing showcases in a third-world country every two years and the presented by Producer Jodi Kaplan / BookingDance at the Edinburgh Fringe. summer Olympics every four years. Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Edinburgh 2009 is a continuation of a cultural exchange between performing You will see seven of the best USA Dance Companies performing at The Fringe for the first time. artists and communities on a global scale. Last summer, coinciding with the Beijing Olympics, Jodi Kaplan Ranging stylistically from classical modern to traditional dance from around the globe, this & Associates produced Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Beijing 2008 as the first of its international productions. diverse program showcases seven innovative -

Zvidance DABKE

presents ZviDance Sunday, July 12-Tuesday, July 14 at 8:00pm Reynolds Industries Theater Performance: 50 minutes, no intermission DABKE (2012) Choreography: Zvi Gotheiner in collaboration with the dancers Original Score by: Scott Killian with Dabke music by Ali El Deek Lighting Design: Mark London Costume Design: Reid Bartelme Assistant Costume Design: Guy Dempster Dancers: Chelsea Ainsworth, Todd Allen, Alex Biegelson, Kuan Hui Chew, Tyner Dumortier, Samantha Harvey, Ying-Ying Shiau, Robert M. Valdez, Jr. Company Manager: Jacob Goodhart Executive Director: Nikki Chalas A few words from Zvi about the creation of DABKE: The idea of creating a contemporary dance piece based on a Middle Eastern folk dance revealed itself in a Lebanese restaurant in Stockholm, Sweden. My Israeli partner and a Lebanese waiter became friendly and were soon dancing the Dabke between tables. While patrons cheered, I remained still, transfixed, all the while envisioning this as material for a new piece. Dabke (translated from Arabic as "stomping of the feet") is a traditional folk dance and is now the national dance of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Palestine. Israelis have their own version. It is a line dance often performed at weddings, holidays, and community celebrations. The dance strongly references solidarity, and traditionally only men participated. The dancers, linked by hands or shoulders, stomp the ground with complex rhythms, emphasizing their connection to the land. While the group keeps rhythm, the leader, called Raas (meaning "head"), improvises on pre-choreographed movement phrases. He also twirls a handkerchief or string of beads known as a Masbha. When I was a child and teenager growing up in a Kibbutz in northern Israel, Friday nights were folk dance nights. -

River North Dance Chicago

Cheryl Mann River North Dance Chicago Frank Chaves, Artistic Director • Gail Kalver, Executive Director The Company: Levizadik Buckins, Taeler Cyrus, Michael Gross, Hank Hunter, Lauren Kias, Ethan R. Kirschbaum, Melanie Manale-Hortin, Michael McDonald*, Hayley Meier, Olivia Rehrman, Ahmad Simmons, Jessica Wolfrum *Performing apprentice Artistic & Production Sara Bibik, Assistant to the Artistic Director • Claire Bataille, Ballet Mistress Joshua Paul Weckesser, Production Stage Manager and Technical Director Mari Jo Irbe, Rehearsal Director • Laura Wade, Ballet Mistress Liz Rench, Wardrobe Supervisor Administration Alexis Jaworski, Director of Marketing • Salena Watkins, Business Manager Diana Anton, Education Manager • Paula Petrini Lynch, Development Manager Christopher W. Frerichs, Grant Writer Lisa Kudo, Development and Special Events Assistant PROGRAM The Good Goodbyes Beat Eva (World Premiere) -Intermission- Three Renatus Forbidden Boundaries Thursday, April 4 at 7:30 PM Friday, April 5 at 8 PM Saturday, April 6 at 2 PM & 8 PM Media support for these performances is provided by WHYY. 12/13 Season | 23 PROGRAM The Good Goodbyes Choreography: Frank Chaves Lighting Design: Todd Clark Music: Original composition by Josephine Lee Costume Design: Jordan Ross Dancers: Taeler Cyrus, Michael Gross, Lauren Kias, Ethan R. Kirschbaum, Melanie Manale-Hortin, Hayley Meier, Jessica Wolfrum Artistic Director Frank Chaves’ newest work, The Good Goodbyes, is an homage to the relationships forged and nurtured within the dance community. Set to an original piano suite by Josephine Lee, artistic director of the acclaimed Chicago Children’s Choir, this wistful and bittersweet work for seven dancers suggests “the beautiful memories and the wonderful relationships I’ve forged with dancers over the years. I want to celebrate the incredibly intimate, intense, fulfilling and—because of the nature of our profession—often short-lived connections we’ve made, and have bid goodbye along the way,” says Chaves. -

On Movement Direction in Musicals. an Interview with Lucy Hind

arts Editorial “It’s All about Working with the Story!”: On Movement Direction in Musicals. An Interview with Lucy Hind George Rodosthenous School of Performance and Cultural Industries, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; [email protected] Received: 22 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract: Lucy Hind is a South African choreographer and movement director who lives in the UK. Her training was in choreography, mime and physical theatre at Rhodes University, South Africa. After her studies, Hind performed with the celebrated First Physical Theatre Company. In the UK, she has worked as movement director and performer in theatres including the Almeida, Barbican, Bath Theatre Royal, Leeds Playhouse Lowry, Sheffield Crucible, The Old Vic and The Royal Exchange. Lucy is also an associate artist of the award-winning Slung Low theatre company, which specializes in making epic theatre in non-theatre spaces. Here, Lucy talks to George Rodosthenous about her movement direction on the award-winning musical Girl from the North Country (The Old Vic/West End/Toronto and recently seen on Broadway), which was described by New York Times critic Ben Brantley as “superb”. The conversation delves into Lucy’s working methods: the ways she works with actors, the importance of collaborative work and her approach to characterization. Hind believes that her work affects the overall “tone, the atmosphere and the shape of the show”. Keywords: choreography; dance; direction; creative team; collaboration; musicals; rehearsals; movement; movement direction 1. Choreography or Movement Direction? George Rodosthenous (GR): Thank you for joining us today for a discussion about your work on the award-winning Girl from the North Country. -

Philadanco! Xmas Philes

Deborah Boardman Deborah THE PHILADELPHIA DANCE COMPANY PHILADANCO! XMAS PHILES Founder, Executive/Artistic Director, DFA, DHL, DA Joan Myers Brown Company Rosita Adamo, Janine Beckles, William E. Burden, Mikaela Fenton, Clarricia Golden, Joe Gonzalez, Jameel M. Hendricks, Victor Lewis Jr., Kareem Marsh, Dana Nichols, Brandi Pinnix, Courtney Robinson, Jah’meek D. Williams, Marcus Williams, Tony Harris (Guest Artist) D/2 Apprentice Company Onederful Ancrum, Ankhtra Battle, Kaniyah Browne, Lindsey Lee, Briana Marshall, Angelica Merced, Dahlia Patterson, Nasir Pittman, Donyae Reaves, Francis Sloane, Taylor Sparks, Lourdes Taylor, Rhapsody Taylor, Dominique Thompson D/3 Youth Ensemble Donovan Blake, Jaheara Brown, Kaniah Browne, Naiya Brown, Arianna Deshields, Nyilah Johnson, Kelsey Jones, Bethany Morris, Mahogani Richardson-Webb, Tiana Smith, Khidir Webster PROGRAM There will be an intermission. Thursday, December 12 @ 7:30 PM Friday, December 13 @ 8 PM Saturday, December 14 @ 2 PM Saturday, December 14 @ 8 PM Zellerbach Theatre The 19/20 dance series is Xmas Philes was commissioned presented by the Annenberg in 2000 by the Annenberg Center Center and NextMove Dance. and NextMove Dance. 19/20 SEASON 51 PROGRAM NOTES Xmas Philes Choreographer Daniel Ezralow Assistant to the Choreographer Debora Chase-Hicks Music Various Artists Lighting Design Clifton Taylor Costume Design Jackson Lowell Costume Execution Natasha Guruleva PRELUDE The Entire Cast WHITE XMAS Tony Harris, Jr. RUDOLPH Rosita Adamo, Janine Beckles, Mikaela Fenton, Clarricia Golden, -

Dance Brochure

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited Dance 2006 Edition Also see www.boosey.com/downloads/dance06icolour.pdf Figure drawings for a relief mural by Ivor Abrahams (courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery) The Boosey & Hawkes catalogue contains many of the most significant and popular scores in the dance repertoire, including original ballets (see below) and concert works which have received highly successful choreographies (see page 9). To hear some of the music, a free CD sampler is available upon request. Works written as ballets composer work, duration and scoring background details Andriessen Odyssey 75’ Collaboration between Beppie Blankert and Louis Andriessen 4 female singers—kbd sampler based on Homer’s Odyssey and James Joyce’s Ulysses. Inspired by a fascination with sensuality and detachment, the ballet brings together the ancient, the old and the new. Original choreography performed with four singers, three dancers and one actress. Argento The Resurrection of Don Juan 45’ Ballet in one act to a scenario by Richard Hart, premiered in 1955. 2(II=picc).2.2.2—4.2.2.1—timp.perc:cyms/tgl/BD/SD/tamb— harp—strings Bernstein The Dybbuk 50’ First choreographed by Jerome Robbins for New York City Ballet 3.3.4.3—4.3.3.1—timp.perc(3)—harp—pft—strings—baritone in 1974. It is a ritualistic dancework drawing upon Shul Ansky’s and bass soli famous play, Jewish folk traditions in general and the mystical symbolism of the kabbalah. The Robbins Dybbuk invites revival, but new choreographies may be created using a different title. Bernstein Facsimile 19’ A ‘choreographic essay’ dedicated to Jerome Robbins and 2(II=picc).2.2(=Ebcl).2—4.2.crt.2.1—timp.perc(2)— first staged at the Broadway Theatre in New York in 1946. -

CV: Choreography and Dance

Leah O’Donnell 917-428-4344 email: [email protected] web: www.Leahfayeodonnell.com Choreographer and performer: dance, dance theater, opera, film and TV. Arts Writer. CHOREOGRAPHY RAD FEST 2020; EPIC CENTER, KALAMAZOO, MI — MARCH 2020 Choreographer: Dance of the Ancestors KALAMAZOO ART HOP 2020; KALAMAZOO, MI — MARCH 2020 Choreographer: Untitled site-specific work EISENHOWER DANCE DETROIT: DANCE MOSAICS; ROCHESTER, MI — 2020 Guest Choreographer for EDD’s Center Dance Ensemble: Blue Burrow THINK TANK 1, AMONG WOMEN; ANDY ARTS CENTER, DETROIT, MI — 2020 Choreographer: Watch Her Disappear NEWDANCEFEST, EISENHOWER DANCE DETROIT; ROCHESTER, MI — 2019. Guest Choreographer: Reverie. MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE, DETROIT OPERA HOUSE — 2018 & 2019 Operetta Summer Workshop Choreographer: Operetta Remix (2019) Operetta Summer Workshop Choreographer: Iolanthe (2018) AMERICAN COLLEGE DANCE ASSOCIATION, NORTHEAST CONFERENCE; SUNY BROCKPORT, NY — 2019 Choreographer: Dance of the Ancestors. Gala selection WOMENS WORK FESTIVAL, KRISTI FAULKNER DANCE, BOLL THEATER; DETROIT, MI — 2019 Choreographer: Reverie JUMP/ CUT: A DANCE ON FILM FESTIVAL; BROOKLYN, NY — 2019 Featured Choreographer and Filmmaker: Eutierria WSU SPRING DANCE CONCERT, BONSTELLE THEATER; DETROIT, MI — 2019 Student Choreographer: Dance of the Ancestors WSU COMPANY ONE MAGGIE ALLESEE THEATER; DETROIT, MI — 2018 — 2019 Student Choreographer for Noel Night Performance and several school tours: Perennials, Dance of the Ancestors WSU DECEMBER DANCE CONCERT, MUSIC HALL CENTER FOR PERFORMING ARTS; DETROIT, MI — 2018 Student Choreographer: Dance of the Ancestors UM GILBERT AND SULLIVAN SOCIETY, LYDIA MENDELSOHN THEATRE; ANN ARBOR, MI — 2016 Choreographer: The Sorcerer DANCE & LIVE PERFORMANCE BIZARRE BAZAAR, COLLEGE FOR CREATIVE STUDIES FUNDRAISER; BIRMINGHAM, MI — 2019 Dancer. Chor. Biba Bell IMPRESSIONIST AND MODERN ART RECEPTION, SOTHEBY’S AUCTION HOUSE; NEW YORK, NY — 2015 Dancer. -

JM Rodriguez HEIGHT: 5’6” | WEIGHT: 135 Lbs

JM Rodriguez HEIGHT: 5’6” | WEIGHT: 135 lbs. HAIR: Brown | EYES: Light Brown ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ FILM The Dreamer Miguel (Male Lead) Marcos Davalos/Tina Landon TELEVISION Hexagon Ep107 Dancing Indian Soldier Fred Tallaksen/Netflix Penny Dreadful Ep#403 Dancer Netflix th 59 Annual Grammy’s: Katy Perry Dancer Daniel Ezralow America’s Got Talent Season 8 SensEtion: Top 60 Brian Burke Angie Tribeca: Episode 2 Bollywood Dancer Steve & Nancy Carell Angie Tribeca: Season Finale Zombie Steve & Nancy Carell Shake It Up: Three’s a Crowd it Up Lead Dancer Joel Zwick/Rosero McCoy Late Night with Jimmy Fallon Plex Shannon Roy-Steen STAGE Arcade Fire: LA Forum 2017 Dancer Melissa Schade Dizzyfeet Foundation LA ’12 Dancer Dana Wilson/Mandy Moore Hysterica – Dance Cam West’s: Get Wet ’13 Dancer Kitty McNamee th DUBLAB 17 Anniversary: Egyptian Lover Dancer Mecca Vazie-Andrews Houston Miller Theater: Bollywood Blast Dancer Kavita Rao Monkey Town 2016: LA Dancer Mecca Vazie-Andrews Yo Gabba Gabba Live Nat. Tour ’11-13 Plex the Robot Dir: Glenn Orsher MUSIC VIDEOS Xbox Zumba Fitness World Party 2 Dancer Katie Boyum/Mellisa Chiz Laura Marlin: Short Asst. Choreographer Kitty Mcnamee Dear White People Dancer Justin Simien/Jamila Glass Laura Marlin: I was an eagle Asst. Choreographer Kitty Mcnamee Penatonix: Ninja Turtles Movie Dancer Nina McNeely Daft Punk/Pharrell: Lose Yourself in Dance Dancer Mecca Vazie Andrews COMMERCIALS CA Lottery: Triple Jackpot Lead Hero Fatima -

Welcometo Northrop Dance Winter Season

WELCOME to Northrop Dance winter season The final work in our winter series is Borderline, a collaboration between choreographers performances! Sébastien Ramirez from France and Honji Wang, who was born and raised in Germany by Korean parents. Their COMPANY WANG RAMIREZ navigates its own borderline between hip-hop and I am grateful to each and every one of you for braving the contemporary dance, defying categories and eagerly exploring new forms. The eye-popping surprise Minnesota cold—perhaps ice, wind and snow—to gather together in Borderline, their Northrop debut, is the use of a rigging system and bungee cords that in the dark to watch dance tonight! The glow of the stage, the exaggerate the dancers’ movements. With leaps and jumps frozen in mid-air, the dancers “swim joy of being here together, and the anticipation of the round the stage like astronauts in zero-gravity.” (Samantha Whittaker/Londondance.com) experience we are about to share—all of this creates a warmth that no Minnesota winter can diminish. I’m thrilled to welcome The work is just over an hour in length, and is split into episodes, some comic, others dark and moody. these next three companies to the Northrop stage. All are Though short, it is utterly engrossing and thought-provoking. Reviews have mentioned themes wonderful artists who have traveled from far and wide and of human relationships—how we build them, and how we tear them apart—but also themes braved their own hurdles to share their work with us. of manipulation, constraint, and the very meaning of democracy. -

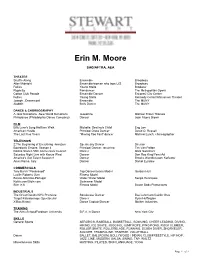

Erin M. Moore

Erin M. Moore SAG/AFTRA, AEA THEATRE Shuffle Along Ensemble Broadway After Midnight Ensemble/woman who taps U/S Broadway Follies Young Stella Brodway Rigoletto Fan dancer The Metropolitan Opera Cotton Club Parade Ensemble Dancer Encores! City Center Follies Young Stella Kennedy Center/Ahmanson Theater Joseph...Dreamcoat Ensemble The MUNY Aladdin Belly Dancer The MUNY DANCE & CHOREOGRAPHY A Jazz Symphony -New World Symphony Josephine Michael Tilson Thomas Philadanco (Philadelphia Dance Company) Dancer Joan Myers Brown FILM Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk Michelle, Destiny'a Child Eng Lee American Hustle Principal Disco Dancer David O. Russell The Last Five Years "Moving Too Fast" dancer Michele Lynch, choreographer TELEVISION Z:The Beginning of Everything -Amazon Speakeasy Dancer Director Boardwalk Empire, Season 4 Principal Dancer, recurring Tim Van Patten Rolling Stones 50th Anniversary Concert Dancer Mark Swanhart Saturday Night Live with Kanye West Dancer Don Roy King/Yemi Ad America's Got Talent Season 8 Dancer Brooke Wendle/Luam Keflezgy Amici Rome, Italy Dancer Daniel Ezralow COMMERCIALS Tory Burch "Possessed" Tap Dancer/Jeans Model Gordon Hull Lucille Roberts Gym Fitness Model Banco Atlanitco-Portugal Under Water Model Sergio Henriques Kohls.com/Style.com Swimwear Model Slim in 6 Fitness Model Beach Body Productions INDUSTRIALS The Great Gatsby NYC Premiere Speakeasy Dancer Baz Luhrmann/Caitlin Gray Target Kaleidoscope Spectacular Dancer Ryan Heffington X-Box Kinect Dance Captain/Dancer Mother Industries TRAINING The Ailey School/Fordham University B.F.A. in Dance New York City SKILLS General Sports AEROBICS, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, BOWLING, CHEER LEADING, DIVING, HIKING, ICE SKATE, JOGGING, JUMP ROPE, PING PONG, ROCK CLIMBER, ROLLER SKATE, ROLLERBLADE, RUNNING, SCUBA DIVER, SNORKELER, SOCCER, TRAMPOLINE, TRAPEZE, VOLLEYBALL Dance BALLET, BALLROOM, BOLLYWOOD / INDIAN, CLUB/FREESTYLE, HIP HOP, JAZZ, LINE, MODERN, SALSA, SWING, TAP, WALTZ Miscellaneous Skills HOSTING, PILATES, SIGN LANGUAGE, YOGA Page 1 of 2 . -

MOMIX • Box 1035 Washington, Connecticut 06793 Tel: 860•868•7454 Fax: 860•868•2317 Email: [email protected] Website

Thursday, November 16 at 7:30pm, 2006 Fine Arts Center Concert Hall Post-performance talk immediately following performance LLUUNNAARR SSEEAA PRESENTED BY MMOOMMIIXX Artistic Director MOSES PENDLETON with DANIELLE ARICO, TOM BARBER, JENNIFER BATBOUTA, SAMUEL BECKMAN, JONATHAN EDEN, ROB LAQUI, EMILY MCARDLE, DANIELLE MCFALL, TIMOTHY MELADY, SARAH NACHBAUER, REBECCA RASMUSSEN, JARED WOOTAN Associate Director CYNTHIA QUINN Production Manager WOODROW F. DICK III Lighting Supervisor JIM BERMAN Technical Director ERIK FULK Company Manager CATE RUSNAK MOMIX • Box 1035 Washington, Connecticut 06793 Tel: 860•868•7454 Fax: 860•868•2317 Email: [email protected] Website: www.momix.com Representation: Margaret Selby Columbia Artists Management, Inc. 1790 Broadway, NYC, NY 10019-1412 Ph: (212) 841-9554 Fax: (212) 841-9770 E-mail: [email protected] Sponsored By PeoplesBank, WGBY TV57 and the Ri8ver 93.9FM Funding provided in part by the New England Foundation for the Arts (NEFA), as part of the NEA Regional Touring Program. NEFA receives major support from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) with additional support coming from the state arts agencies of New England. LUNAR SEA PART 1 Sea of Tranquility Co-commissioned by the Aspen/Santa Fe Ballet and the Nutmeg Conservatory for the Arts in Torrington, CT PART 2 Bay of Seething Performance time is approximately 85 minutes. Post-performance talk immediately following performance Conceived & Directed by: MOSES PENDLETON Assisted by: Danielle Arico, Samuel Beckman, Ty Cheng, Otis Cook, Simona Di Tucci, -

Pilobolus Dance Theater

Nadirah Zakariya Nadirah Presented by Dance Affiliates and Annenberg Center Live PILOBOLUS DANCE THEATER Executive Producer Itamar Kubovy Artistic Directors Robby Barnett and Michael Tracy Associate Artistic Directors Renée Jaworski and Matt Kent Dancers: Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Antoine Banks-Sullivan, Krystal Butler, Benjamin Coalte, Jordan Kriston, Derion Loman, Mike Tyus Dance Captain Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern Production Manager Kristin Helfrich Production Stage Manager Shelby Sonnenberg Lighting Supervisor Mike Faba Video Technician Molly Schleicher Éminence Grise Neil Peter Jampolis Stage Ops Eric Taylor PROGRAM On The Nature of Things The Transformation Automaton // Intermission // [esc] Day Two //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Thursday, May 7 at 7:30 PM Friday, May 8 at 8 PM Saturday, May 9 at 3 PM and 8 PM Sunday, May 10 at 3 PM Zellerbach Theatre 30 // ANNENBERG CENTER LIVE PROGRAM NOTES Pilobolus Is A Fungus Edited by: Oriel Pe’er and Paula Salhany Score by: Keith Kenniff On The Nature Of Things (2014) Created by: Robby Barnett, Renée Jaworski, Matt Kent, and Itamar Kubovy in collaboration with Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Benjamin Coalter, Matt Del Rosario, Eriko Jimbo, Jordan Kriston, Jun Kuribayashi, Derion Loman, Nile Russell, and Mike Tyus Performed by: Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Jordan Kriston and Mike Tyus Music: Vivaldi; Michelle DiBucci and Edward Bilous Mezzo Soprano: Clare McNamara Violin Solo: Krystof Witek Lighting and Set Design: Neil Peter Jampolis On The Nature Of Things was commissioned by The Dau Family Foundation in honor of Elizabeth Hoffman and David Mechlin; Treacy and Darcy Beyer; The American Dance Festival with support from the SHS Foundation and the Charles L. and Stephanie Reinhart Fund; and by the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes a great nation deserves great art.