Producing and Contesting Place on the Atlanta Beltline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta Neighborhoods Reap

Vol. 4, Issue 2 | 1st Quarter 2011 BEACHAM Your Monthly Market Update From 3284 Northside Parkway The Best People in Atlanta Real Estate™ Suite 100 Atlanta, GA 30327 404.261.6300 Insider www.beacham.com Home sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta What’s neighborhoods reap the benefits of an early spring Hot The luxury market. There he spring selling season came early for many intown real estate markets like Buckhead and the were 13 sales homes in metro Atlanta priced neighborhoods in Buckhead and what is rest of the Atlanta are varied according to Carver. $2 million or more in considered “In-town Atlanta” (Ansley Park, East First and foremost, Buckhead is a top housing draw T the first quarter (11 in Buckhead, Midtown, Morningside, Virginia-Highlands), in any market because of its proximity to the city’s Buckhead, 2 in East Cobb), where single family home sales collectively rose 21% greatest concentration of exceptional homes, high a 63% increase from from the first quarter of 2010 and prices increased 6%. paying jobs, shopping, restaurants, schools, etc. the first quarter a year The story was not as rosy for the rest In March, more than With an average home sale price ago. However, sales are of metro Atlanta, however. While single of $809,275 in the first quarter, still 32% below the first family home sales were up 5% in the first 15% of our new listings Buckhead is an affluent community quarter of 2007 when the quarter, prices were down 8% from a year went under contract and the affluent have emerged luxury market was peaking. -

990-PF, Year 2013, Part I, Line 25 and Part XV, Line 3A GRANTS PAID in 2013

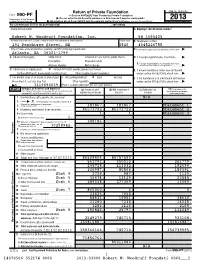

Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department of the Treasury | Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Internal Revenue Service | Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number Robert W. Woodruff Foundation, Inc. 58-1695425 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 191 Peachtree Street, NE 3540 4045226755 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here~| Atlanta, GA 30303-1799 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~| Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~| H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~| I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: X Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~| | $ 3119096039. -

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

The Atlanta Preservation Center's

THE ATLANTA PRESERVATION CENTER’S Phoenix2017 Flies A CELEBRATION OF ATLANTA’S HISTORIC SITES FREE CITY-WIDE EVENTS PRESERVEATLANTA.COM Welcome to Phoenix Flies ust as the Grant Mansion, the home of the Atlanta Preservation Center, was being constructed in the mid-1850s, the idea of historic preservation in America was being formulated. It was the invention of women, specifically, the ladies who came J together to preserve George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The motives behind their efforts were rich and complicated and they sought nothing less than to exemplify American character and to illustrate a national identity. In the ensuing decades examples of historic preservation emerged along with the expanding roles for women in American life: The Ladies Hermitage Association in Nashville, Stratford in Virginia, the D.A.R., and the Colonial Dames all promoted preservation as a mission and as vehicles for teaching contributive citizenship. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held in Piedmont Park here in Atlanta featured not only the first Pavilion in an international fair to be designed by a woman architect, but also a Colonial Kitchen and exhibits of historic artifacts as well as the promotion of education and the arts. Women were leaders in the nurture of the arts to enrich American culture. Here in Atlanta they were a force in the establishment of the Opera, Ballet, and Visual arts. Early efforts to preserve old Atlanta, such as the Leyden Columns and the Wren’s Nest were the initiatives of women. The Atlanta Preservation Center, founded in 1979, was championed by the Junior League and headed by Eileen Rhea Brown. -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

THE Inman Park

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association November 2015 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 43 • Issue 11 Coming Soon BY DENNIS MOBLEY • [email protected] Inman Park Holiday Party I’m pr obably showing my Friday,2015 December 11 • 7:30 pm – 11:00 pm age, but I can remember the phrase “coming soon to a The Trolley Barn • 963 Edgewood Avenue theater near you” like it was yesterday. In this case, I The annual Inman Park Holiday Party returns wanted to give our readers a heads-up as to what they can to The Trolley Barn this year. Don’t miss this expect with our conversion to chance to meet and visit with fellow Inman President’s Message the MemberClicks-powered Park neighborsHoliday over food, drinks Party and dancing. IPNA website and associated membership management software. Enjoy heavy hors d’oeuvres catered by Stone By the time you read this November issue of the Advocator, some Soup and complimentaryAnnouncement beer and wine. A 400+ of you will have received an email from our Vice President DJ will be there to spin a delightful mix of old of Communications, James McManus, notifying you that you standards and newMissing favorites. So don your are believed to be a current IPNA member in good standing. (We holiday fi nest and join us for a good time! gleaned this list of 400+ from our current database and believe it to be fairly accurate). -

November 2012

November 2012 News for Candler Park Your In Town Hometown www.CandlerPark.org Candler Park Candler Park golf Course Neighborhood Organization Named One of Ten Officer Elections “Places in Peril” by LExa KiNg, CPNO MEMbErshiP OffiCEr from the georgia Trust for i think it serves us well to remember why CPNO meets historic Preservation every month and why we go through the exercise The georgia Trust for historic Preservation has annually of seeking people to run for our board of announced its 2013 list of ten Places in Peril in the Directors positions. state, and Candler Park golf Course and clubhouse are included. MissiON Of CPNO: The purpose of the neighborhood organization shall be to promote the common good and “This is the Trust’s eighth annual Places in Peril list,” general welfare in the neighborhood known as Candler said Mark C. McDonald, president and CEO of the Trust. Park in the City of atlanta, georgia. “We hope the list will continue to bring preservation action to georgia’s imperiled historic resources by That said, to agree to serve on the board of Directors highlighting ten representative sites.” of CPNO is a remarkable opportunity and responsibility. as with many volunteer positions, what is seen by most Places in Peril is designed to raise awareness about of the participants of any organization is a small part georgia’s significant historic, archaeological and cultural of the dedication and energy that is expended by the resources, including buildings, structures, districts, leaders. some of the efforts of these volunteers are: archaeological sites and cultural landscapes that are threatened by demolition, neglect, lack of maintenance, • Monthly board and membership meetings, special inappropriate development or insensitive public policy. -

Neighborhood Improvement Association Manny's Volume Twenty-Eight • Issue Number Four • April 2019 Page 5 Neighbor

Cabbagetown Neighborhood Improvement Association Manny's Volume Twenty-eight • Issue Number Four • April 2019 Page 5 Neighbor "If everyone demanded peace instead of another television set, then there'd be peace.” ~ John Lennon Neighborhood Meeting The next neighborhood meeting will be held on Tuesday, Apr. 9th, 6:45p at Are Y'all Aboard? the Cabbagetown Community Center. By Sean Keenan, Curbed Atlanta AGENDA A collective of neighborhood organizations Lord Aeck Sargent urban designer Matt I. Welcome and announcements is raising tens of thousands of dollars to Cherry said the firm began working on II. Review & approval of March minutes enlist an architecture firm to help draft the project last week and plans to host III. Atlanta Police Department a redevelopment plan for Hulsey Yard, a pop-up studios to help inform the four IV. City of Atlanta – Valencia Hudson colossal chunk of intown railroad property neighborhoods’ vision for the site. V. Financial Report – that isn’t even for sale. He understands this approach to urban Saundra Reuppel, Treasurer Talk about community pro-activism. planning isn’t exactly traditional. VI. Committee Reports “Is it unorthodox? Yes. Is it something Atlanta • NPU – John Dirga, But to some, this initiative, spearheaded by needs? Undoubtedly,” Cherry said, noting that Cabbagetown Representative residents from Cabbagetown, Reynoldstown, starting a community-led conversation now • Historic Preservation and Land Use Old Fourth Ward, and Inman Park – the is better for neighborhoods than waiting for a Committee – Nicole Seekely, Chair neighborhoods lining the roughly 70-acre CSX major developer to conjure its own vision. 1. 195 Pearl Street - Type III CoA - Transportation property stretched along DeKalb Rear addition, side dormer, Avenue – is little more than a pipe dream. -

Feasibility Study for Mcmichael Property in Historic South Atlanta Center for Leadership and Mtap Team

Feasibility Study for McMichael Property in Historic South Atlanta Center for Leadership and mTap Team Urban Land Institute’s Architect Jason Snyder Center for Leadership is a Gensler 9 month program for real estate industry professionals Developer Mike Green Pansophy Capital Partners with at least 7 years experience who have a Economic Development Ashley Jones vision for Atlanta’s future and Invest Atlanta a commitment to community Commercial Broker Inga Harmon service and civic Harmon & Harmon Realtors engagement. Zoning Attorney Julie Sellers Pursley Friese Torgrimson Presentation Overview • Executive Summary • Market Study • Zoning • Design • Financials • Recommendation 2 Executive Summary Issue:Feasibility study for increased residential density development of 4 acres of vacant property FCS owns in Historic South Atlanta. Summary: The mTap team evaluated the site, regulations, market, design, community desires, and financial aspects for future development. The McMichael Property is well situated for a multifamily development that maintains and respects the historic and residential fabric of the community. Haven @ South Atlanta achieves the objectives of FCS and provides new housing opportunities. “Common Ground” FCS Mission mTap Mission “Empowering neighborhoods “Creating a holistic to thrive under the belief that community through all people have value, dignity, innovative use of land for and something to offer to the families.” community.” Historic South Atlanta Background ▪ Neighborhood developed during Reconstruction after the -

Subarea 5 Master Plan Update March 2021

ATLANTA BELTLINE SUBAREA 5 MASTER PLAN UPDATE MARCH 2021 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 1 1.1 Overview 2 1.2 Community Engagement 4 2. Context 13 2.1 What is the Atlanta BeltLine? 14 2.2 Subarea Overview 16 3. The Subarea Today 19 3.1 Progress To-Date 20 3.2 Land Use and Design/Zoning 24 3.3 Mobility 32 3.4 Parks and Greenspace 38 3.5 Community Facilities 38 3.6 Historic Preservation 39 3.7 Market Analysis 44 3.8 Plan Review 49 4. Community Engagement 53 4.1 Overall Process 54 4.2 Findings 55 5. The Subarea of the Future 59 5.1 Goals & Principles 60 5.2 Future Land Use Recommendations 62 5.3 Mobility Recommendations 74 5.4 Parks and Greenspace Recommendations 88 5.5 Zoning and Policy Recommendations 89 5.6 Historic Preservation Recommendations 92 5.7 Arts and Culture Recommendations 93 Image Credits Cover image of Historic Fourth Ward Park playground by Stantec. All other images, illustrations, and drawings by Stantec or Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. unless otherwise noted. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - iv Atlanta BeltLine Subarea 5 Master Plan — March 2021 SECTION HEADER TITLE - SECTION SUBHEADER INFORMATION 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Report Title — Month, Year EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - OVERVIEW 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1.1 OVERVIEW Subarea 5 has seen more development activity Looking forward to the next ten years, this plan than any subarea along the Atlanta BeltLine update identifies a series of recommendations over the past decade. The previous subarea plan and strategic actions that build on prior growth to was adopted by City Council in 2009, the same ensure that future development is in keeping with year construction started on the first phase of the community’s collective vision of the future. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

Old Fourth Ward Neighborhood Master Plan 2008

DRAFT - September 8, 2008 Neighborhood Master Plan Sponsored by: Kwanza Hall, Atlanta City Council District 2 Poncey-Highland Neighborhood Association Prepared by: Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates April 29, 2010 City of Atlanta The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Atlanta City Council Ceasar Mitchell, President Carla Smith, District 1 Kwanza Hall, District 2 Ivory Lee Young Jr., District 3 Cleta Winslow, District 4 Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Alex Wan, District 6 Howard Shook, District 7 Yolanda Adrian, District 8 Felicia A. Moore, District 9 C.T. Martin, District 10 Keisha Bottoms, District 11 Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 At-Large Aaron Watson, Post 2 At-Large H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 At-Large Department of Planning and Community Development James Shelby, Commissioner Bureau of Planning Charletta Wilson Jacks, Acting Director Garnett Brown, Assistant Director 55 Trinity Avenue, Suite 3350 • Atlanta, Georgia 30303 • 404-330-6145 http://www.atlantaga.gov/government/planning/burofplanning.aspx ii Acknowledgements Department of Public Works Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates Michael J. Cheyne, Interim Commissioner Caleb Racicot, Senior Principal Adam Williamson, Principal Department of Parks Jia Li, Planner/Designer Paul Taylor, Interim Commissioner Woody Giles, Planner Atlanta Police Department, Zone 5 Service Donations The following organizations provided donations of time and Major Khirus Williams, Commander services to the master planning process: Atlanta Public Schools American Institute of Architects,