STORAGE WARS Solving the Archaeological Curation Crisis? Author(S): Morag M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P Arsons 72-Hour Sale!

3620 N. Hwy. 47 3620 N.Hwy. POSTAL PATRON Mufflers Brake Work Rotations Tire your needs! for all See us FULL-SERVICE AUTO/TRUCK REPAIR AUTO/TRUCK FULL-SERVICE NORTH WOODS A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW $ AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS HOME OFTHE 17 PRSRT STD *5-qt. maximum OIL CHANGE OIL www.rhinelanderchrysler.com ECRWSS U.S. Postage 95 PAID * Saturday, Permit No. 13 Eagle River Sept. 13, 2014 (715) 479-4421 AWARD-WINNING NEWSCOVERAGE AWARD-WINNING © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING 5353 Hwy. 70 West 715-420-1555 Eagle River, WI 54521 (800) 341-4421 NOW AVAILABLE ONTHE AVAILABLE NOW ParsonsParsonsof Eagle River • Radiator • FuelInjection • Transmission Alignments 10% $ All Flushes 39 OFF 95 2011 Chevy Traverse Stk# 7921 ONLY $22,771* SEPT. 18, 19 & 20 2011 Chevy ONLY! Silverado LTZ vcnewsreview.com vcnewsreview.com PARSONS 72-HOUR SALE! 36,003 miles 2014 Chevy Silverado 2014 Chevy Silverado 2014 Chevy Silverado Stk# 3882 $ Regular Cabs Double Cabs Crew Cabs ONLY 29,876 STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT 2011 Chevy Silverado LTZ 26,581 miles $ $ $ Stk# 7527 26,147 24,999 36,694 $ OR OR OR ONLY 30,476 2013 Chevy Malibu $ $ $ 24,848 miles 307 PER MO.* 358 PER MO.* 453 PER MO.** Stk# 7589 $ 2015 Chevy Silverado 2015 Chevy Silverado 2015 Chevy Equinox 2014 Buick ONLY 18,347 2500 Monroe Utility Body 3500 Monroe Tippers Encore AWD 2014 Chevy Camaro 17,463 miles Stk# 2538 $ ONLY 26,389 2013 Chevy Captiva Stk# 9942 STARTING AT STARTING AT Stk# 5662 34,077 miles Stk# 9381 $ $ $ $ $ 40,984*** 43,773*** 24,550* 25,229* ONLY 19,989 2010 Chevy Traverse Shop Us Last to Save the Most! 67,679 miles Stk# 7807 * To approved credit for 72 months only. -

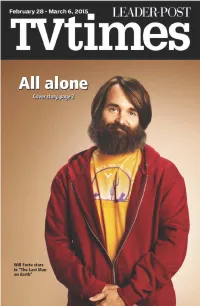

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2015 “Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder Mark A. Rademacher Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rademacher, Mark A., "“Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder" (2015). Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication. 100. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/100 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder Mark A. Rademacher These are the rules of storage auctions. This is a cash only sale. All sales are final. We're gonna cut the lock. We're gonna open the door. You're gonna have five minutes to look. You cannot go inside the unit, you cannot open any boxes. We are gonna sell this to the highest cash bidder. Are you ready to go? Dan Dotson, Storage Wars Auctioneer (“High Noon in the High Desert”) With these basic rules, auctioneer Dan Dotson sets the stage for the drama that unfolds during A&E Network's popular reality TV (RTV) program Storage Wars (2010–). -

Pastor's Column

St. Thomas More CatholicG Church 1 September 14, 2014 SAINT So the Son of Man must be lifted up. THOMAS John 3:15 MORE CATHOLIC CHURCH A Roman Catholic Parish Exaltation of the Holy Cross in the Diocese of San Diego September 14, 2014 Spirituality The Rite of Christian Burial for Tradition Most Reverend Cirilo Flores Community (1948-2014) Fifth Bishop of San Diego Mass Schedule Saturday at 5:00pm Sunday at 8:30am and 10:30am Reception of the Body Funeral Mass Monday-Friday at 8:15am Saint Joseph Cathedral Saint Thérèse of Carmel 1535 Third Avenue, San Diego 92101 4355 Del Mar Trails Road Eucharistic Adoration 10:00am, Tuesday, September 16 San Diego 92130 Monday-Friday, 6:30am-7:30pm 12:00noon, Wednesday, September 17 Visitation at Saint Joseph Cathedral Reconciliation (Confession) 10:15am-6:45pm, Tuesday, September 16 Commital Saturday, 4:00-4:30pm Vigil for the Deceased Holy Cross Cemetery Saint Joseph Cathedral 4470 Hilltop Drive, San Diego 7:00pm, Tuesday, September 16 After Funeral Mass Rev. Michael Ratajczak, Pastor Wednesday, September 17 Rev. Karl Bauer, Senior Priest Deacon John Fredette The funeral rites are open to the public, but seating may be limited. Deacon Thomas A. Goeltz Rev. Michael Ratajczak 1450 South Melrose Drive 760-758-4100 x100 Oceanside, CA 92056 Pastor’s Column [email protected] 760-758-4100 760-758-4165 fax Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross Office Hours: Monday-Friday, 8:30am-12:00noon On the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (or Triumph of the Cross) we honor the and 12:30-4:00pm Holy Cross by which Christ redeemed the world. -

P25tv Layout 1

THURSDAY, AUGUST 31, 2017 TV PROGRAMS And Cat Noir 14:15 Future-Worm! 21:00 Ancient Aliens 05:48 SpongeBob SquarePants 19:30 Less Than Perfect 19:30 Food Factory USA 14:30 EastEnders 11:55 Disney Mickey Mouse 14:40 Kirby Buckets 22:00 Bible Secrets Revealed 06:12 SpongeBob SquarePants 20:00 The Tonight Show Starring 19:55 Food Factory USA 15:00 Death In Paradise 12:00 Welcome To The Ronks 15:05 Lab Rats: Bionic Island 23:00 How 2 Win 06:36 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Jimmy Fallon 20:20 How Do They Do It? 15:55 Doctor Who 12:15 Hank Zipzer 15:30 Walk The Prank 07:00 The Loud House 21:00 Seinfeld 20:45 Food Factory 16:45 Stella 12:40 Dog With A Blog 15:55 Right Now Kapow 07:24 Rabbids Invasion 21:30 Seinfeld 21:10 Science Of The Movies 17:30 New Tricks 00:00 Escaping Polygamy 13:05 Star Darlings 16:25 K.C. Undercover 07:48 Get Blake 22:00 Modern Family 22:00 Food Factory USA 18:20 Carters Get Rich 01:00 Celebrity Ghost Stories 13:10 Good Luck Charlie 16:50 Kirby Buckets Warped 08:12 Harvey Beaks 22:30 Modern Family 22:25 Food Factory USA 18:45 EastEnders 02:00 My Haunted House 13:35 Austin & Ally 17:15 Mech-X4 08:36 Sanjay And Craig 23:00 The Big C 19:15 Death In Paradise 03:00 My Haunted Vacation 14:00 Jessie 17:40 Gravity Falls 09:00 Rank The Prank 23:30 Late Night With Seth Meyers 20:10 Holby City 04:00 Escaping Polygamy 14:25 Lolirock 18:05 Disney Mickey Mouse 00:20 Counting Cars 09:24 Henry Danger 21:00 Carters Get Rich 05:00 Celebrity Ghost Stories 14:50 The Zhuzhus 18:10 Milo Murphyʼs Law 00:45 Counting Cars 09:48 100 Things To Do Before 21:30 Mum 06:00 It Takes A Killer 15:15 Whisker Haven Tales With 18:35 Disney11 01:10 Forged In Fire High School 22:00 Uncle 08:00 The First 48 The Palace Pets 19:00 Disney11 02:00 Hunting Hitler 10:12 Game Shakers 09:00 Homicide Hunter 15:20 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug 19:25 K.C. -

Child Tax Credits Are Expected to Drastically Reduce Child Poverty in Michigan

___ • Watch Live Menu Quick links... ADVERTISEMENT Be prepared with State Farm Life Insurance. State Farm Life Insurance Company (Not licensed in MA, NY or WI) State Farm and Accident Assurance Company (Licensed in NY and WI) Bloomington, IL NEIGHBORHOODS STATE CAPITOL Child tax credits are expected to drastically reduce child poverty in Michigan --> Play Video Pause Unmute Current Time 0:35 This/ is a modal window. Duration Time 2:39 Child tax credits which provide monthly payments to many Michigan families are expected to roll out this week. By: Elle Meyers Posted at 7:04 PM, Jul 13, 2021 and last updated 7:04 PM, Jul 13, 2021 LANSING, Mich. — Eligible Michigan families with children will receive payments directly to their bank accounts starting this week as part of the expanded child tax credit from the federal government, which was prompted by the economic effects of he pandemic. Experts estimate this will cut child poverty by nearly half, a move the United States has never seen before. “These will be monthly payments to families that will show up in their bank accounts based on the number of children they have and their income level," said Matt Gillard who serves as president and CEO of Michigan's Children, a Lansing based advocacy group. Families across mid-Michigan will be eligible for up to $300 per month, per child. Recent Stories from fox47news.com ' “The credits vary depending upon the age of the child and they vary as well based on the family income but they are designed in a way to truly benefit families on a monthly basis to meet the high costs that they’re incurring in raising children, he said." Families making up to $150,000 a year and single parents making up to $112,500 per year are eligible for the monthly payments. -

A16 TV Friday [16-16].Indd

16 TIMES-TRIBUNE / FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 ENTERTAINMENT , FRIDAY PRIME TIME MARCH 9, 2012 PEOPLE IN THE NEWS 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 BROADCAST ABC & WATE 6 ABC World News & Judge Judy & Judge Shark Tank Body jewelry; organic Primetime: What Would You Do? 20/20 (N) ’ Å & WATE 6 (:35) Nightline News at 6 With Diane Saw- D Entertain- Judy Å skin care. (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å News at 11 (N) Å WATE & D ABC 36 yer (N) Å ment Tonight D The Insider D ABC 36 WTVQ D News at 6 (N) Å News at 11 Ky. company sues CBS Y News CBS Evening Y Season College Basketball SEC Tournament, Third Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From New Orleans. (N) College Basketball SEC Tournament, Fourth Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From ( Local 8 News News With Scott Special (Live) New Orleans. (N) (Live) WYMT Y ; Newsfirst at Pelley (N) ’ Å ( Entertain- WVLT ( 6:00pm ment Tonight WKYT ; ; Wheel of to stop name airing Fortune NBC 2 LEX 18 News NBC Nightly 2 LEX 18 2 Access Hol- Who Do You Think You Are? “Je- Grimm “Plumed Serpent” Investigat- Dateline NBC (N) ’ Å 2 LEX 18 News (:35) The Tonight at 6 (N) Å News (N) ’ Å NEWS lywood rome Bettis” Retired football player ing an arson-related homicide. (N) at 11 Show With Jay WLEX 2 * News (N) * Wheel of * Jeopardy! Jerome Bettis. (N) ’ Å ’ Å * 10 News Leno Å WBIR * Fortune Nightbeat on Limbaugh FOX Judge Judy ’ Å Judge Judy ’ Å Two and a Half The Big Bang Kitchen Nightmares “Blackberry’s; Leone’s” Improving a New Jersey eatery. -

Tuesday Morning, May 8

TUESDAY MORNING, MAY 8 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Ricky Martin; Giada De Live! With Kelly Stephen Colbert; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Laurentiis. (N) (cc) (TV14) Miss USA contestants. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Rhyming Block. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Three new nursery rhymes. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Iden- 12/KPTV 12 12 tity Crisis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the It’s Supernatural Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) (TVG) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (N) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court (N) The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter A fugitive and Criminal Minds The team must Criminal Minds Hotch has a hard CSI: Miami Inside Out. -

Epa Holding a Public Comment Period and Public Meeting

June 2019 | Debahjimon Ode'imini-giizis • Strawberry Moon 11 Ima (White) and (Jolene Kegg) Staples of Cass Lake, brother; William Bobolink Bruce Bobolink of Bena, sister; Gloria on April 11, 1948 (Duane) Beaudreau of Cass Lake, special in Battle Point, granddaughters in New York; Linda Kegg MN. and Angelia Baker, grandchildren; Skylare, Sarrell, Donavan, William, Larrissa, Kelli, EPA Holding a Public Comment Period and Joann loved Kenny, Nigoni, William, Rosalie, Markell, Public Meeting on a Proposed Cleanup Plan going to bingo Kyle, and Robin, numerous great grand- St. Regis Paper Co. Superfund Site and playing the children, nieces; Patricia, Barbara and Jenny, Leech Lake Reservation, Cass County, Minnesota slot machines at nephews; Warren and Aaron, her bingo the casino. She partners; Armella Charwood and Alberta also enjoyed Jones, other family members and friends. Public Comment Period: June 17 – Aug. 15, 2019 going to pow- Public Meeting: July 30, 2019, 6 p.m. wows, watching A wake for Joann will begin at 6:00 p.m., Storage Wars Saturday, May 18 and continue until her U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently completed a study of the St. Regis Paper Co. and Lifetime 11:00 a.m. funeral service on Monday, May Superfund site and has issued a proposed plan that evaluated several alternatives for cleaning up pollution from the residential area. EPA is proposing to remove contaminated soil from affected residential areas and movies. What Joann loved most was being 20 all being held at the Veteran’s Memorial replace it with clean soil, manage most of the removed soil at an on-site facility, monitor the soil stored with all of her grandchildren and great Building in Cass Lake, MN. -

High Desert Report Is Dedicated to the Memory of Willie Pringle Spring 2015 L Volume 54 The

The 54th edition of the High Desert Report is dedicated to the memory of Willie Pringle Spring 2015 l Volume 54 The RADCO CompaniesHigh Desert Report An economic overview of the High Desert region affiliated with The Bradco Companies, a commercial real estate group I wish to welcome As a part of our history, in late 1992, cial broker ever inducted, and I am very our current, future, when a friend of mine, Ms. Cele Under- humbled to be a part of this great hon- and long stand- wood, then an Associate with the Keith orary society for the advanced and land ing subscribers and Companies, a company with which we economics. sponsors of the shared office space, suggested that, with We also had a delay in this edition with 54th Edition of the all the development, bus tours and sem- the recent addition of a new member of Bradco High Des- inars in Southern California, we create our family, Mr. Parker Sinibaldi, Ms. ert Report, the first a newsletter. Having no knowledge of Kaitlin Alpert’s son. Parker was born on and only economic how to do a newsletter, I contacted my December 9, 2014, and Ms. Alpert has overview of the long-time friend and mentor, Dr. Alfred just been able to return to work to as- High Desert region, covering the north- Gobar, then Chairman of Alfred Gobar sist us on the Bradco High Desert Re- ern portion of San Bernardino County & Associates (Brea/Anaheim, Califor- port and many of the other endeavors and the Inland Empire. -

Uitzendschema Branddeli.Xlsx

UITZENDSCHEMA september 2015 SSWT 0,00 Campaign period 7 t/m 20 september MTVH = MTV CFNL = Comedy Central Family Budget € 37.000,00 CCH = Comedy Central TLCNL = TLC Demographic 13‐24 No. of Ratings 51,45 Break area Campaign Advertiser Product Duration Day TX time Programm Category Ratings Scheduled Date : 07/09/2015 MTVH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 9:39:13 3 FROM 1 0,23 CCH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 9:46:14 MY NAME IS EARL 0,13 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 10:01:33 MARRIED WITH CHILDREN 0,01 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 11:23:23 THE GRAHAM NORTON SHOW 0,01 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 12:16:10 SAMANTHA WHO? 0,01 MTVH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 12:16:32 FAKING IT 0,31 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 12:40:17 SAMANTHA WHO? CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 13:05:07 DHARMA AND GREG MTVH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 13:10:14 CATFISH: THE TV SHOW 0,34 FOX 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 14:06:56 RAISING HOPE Y1 0,19 CCH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 14:19:17 FUTURAMA 0,04 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 14:19:38 MY WIFE AND KIDS MTVH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 14:30:02 TEEN MOM 2 0,23 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 14:42:47 MY WIFE AND KIDS 0,03 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 15:35:07 DHARMA AND GREG 0,01 MTVH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 15:48:24 THE HILLS 0,32 CCH 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 17:47:59 SOUTH PARK 0,84 TLCNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 18:20:00 CAKE BOSS - DNI - SEASON 7 EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW 0,45 CFNL 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 20:30:44 3RD ROCK FROM THE SUN FOX 45612 SSWT SSWT 30 + 10 Mon 20:50:07 STORAGE WARS -

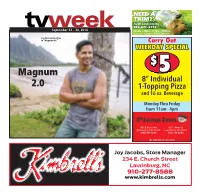

Magnum P.I.” Carry out Weekdaymanager’S Spespecialcial $ 2 Medium 2-Topping Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5And 16Each Oz

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 22 - 28, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 Jay Hernandez stars in “Magnum P.I.” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday from 11am - 4pm 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 22, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Back to the well: ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to television with CBS reboot By Kenneth Andeel er One,” 2018) in the role of Higgins, dependence on sexual tension in TV Media the straight woman to Magnum’s the new formula. That will ultimate- wild card, and fellow Americans ly come down to the skill and re- ame the most famous mustache Zachary Knighton (“Happy End- straint of the writing staff, however, Nto ever grace a TV screen. You ings”) and Stephen Hill (“Board- and there’s no inherent reason the have 10 seconds to deduce the an- walk Empire”) as Rick and TC, close new dynamic can’t be as engrossing swer, and should you fail, a shadowy friends of Magnum’s from his mili- as its prototype was. cabal of drug-dealing, bank-rob- tary past. There will be other notable cam- bing, helicopter-hijacking racketeers The pilot for the new series was eos, though.