Plan for Talk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Do Ideas Come From?

Where do ideas come from? Where do ideas come from? 1 Where do ideas come from? At Deutsche Bank we surround ourselves with art. International contemporary art plays its part in helping us to navigate a changing world. As a global bank we want to understand, and engage with, different regions and cultures, which is why the Deutsche Bank Collection features contemporary artists from all over the globe. These artists connect us to their worlds. Art is displayed throughout our offices globally, challenging us to think differently, inviting us to look at the world through new eyes. Artists are innovators and they encourage us to innovate. Deutsche Bank has been involved in contemporary art since 1979 and the ‘ArtWorks’ concept is an integral part of our Corporate Citizenship programme. We offer employees, clients and the general public access to the collection and partner with museums, art fairs and other institutions to encourage emerging talent. Where do ideas come from? 2 Deutsche Bank reception area with artworks by Tony Cragg and Keith Tyson Art in London The art in our London offices reflects both our local and global presence. Art enriches and opens up new perspectives for people, helping to break down boundaries. The work of artists such as Cao Fei from China, Gabriel Orozco from Mexico, Wangechi Mutu from Kenya, Miwa Yanagi from Japan and Imran Qureshi from Pakistan, can be found alongside artists from the UK such as Anish Kapoor, Damien Hirst, Bridget Riley and Keith Tyson. We have named conference rooms and floors after these artists and many others. -

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer Barbican Art Gallery, London, UK 7 October 2020 – 3 January 2021 Media View: 6 October 2020 #MichaelClark @barbicancentre The exhibition has been recognised with a commendation from the Sotheby’s Prize 2019. Michael Clark, Because We Must, 1987 © Photography by Richard Haughton This Autumn, Barbican Art Gallery stages the first ever major exhibition on the groundbreaking dancer and choreographer Michael Clark. Exploring his unique combination of classical and contemporary culture, Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer unfolds as a constellation of striking portraits of Clark through the eyes of legendary collaborators and world-renowned artists including Charles Atlas, BodyMap, Leigh Bowery, Duncan Campbell, Peter Doig, Cerith Wyn Evans, Sarah Lucas, Silke Otto-Knapp, Elizabeth Peyton, The Fall and Wolfgang Tillmans. 2020 marks the 15th year of Michael Clark Company’s collaboration with the Barbican as an Artistic Associate. This exhibition, one of the largest surveys ever dedicated to a living choreographer, presents a comprehensive story of Clark’s career to date and development as a pioneer of contemporary dance who challenged the furthest intersections of dance, life and art through a union of ballet technique and punk culture. Films, sculptures, paintings and photographs by his collaborators across visual art, music and fashion are exhibited alongside rare archival material, placing Clark within the wider cultural context of his time. Contributions by cult icons of London’s art scene establish his radical presence in Britain’s cultural history. Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts, Barbican said: “We’re thrilled to be sharing this rare opportunity for audiences to get to know the inspirational work of one of the UK’s most influential choreographers and performers, Michael Clark. -

The Art of Quotation. Forms and Themes of the Art Quote, 1990–2010

The Art of Quotation. Forms and Themes of the Art Quote, 1990–2010. An Essay Nina Heydemann, Abu Dhabi I. Introduction A “Japanese” Mona Lisa? An “improved” Goya? A “murdered” Warhol? In 1998, the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura staged himself as Mona Lisa.1 Five years later, the British sibling duo Jake and Dinos Chapman ‘rectified’ Francisco de Goya’s etching series „The Disas- ters of War“ by overpainting the figures with comic faces.2 In 2007, Richard Prince spoke about his intention in the 1990s of having wanted to murder Andy Warhol.3 What is it in artists and artworks from the past that prompts so many diverse reactions in contempo- rary art today? In which forms do contemporary artists refer to older works of art? And what themes do they address with them? This paper is an extract of a dissertation that deals with exactly these questions and analyses forms and themes of art quotes.4 Many 1 In the series „Mona Lisa – In Its Origin, In Pregnancy, In The Third Place“ Yasumasa Morimura raised questions of his Japanese identity and hybrid sexuality based on Leonardo da Vinci’s masterwork. 2 Jake Chapman quoted in the Guardian: "We always had the intention of rectifying it, to take that nice word from The Shining, when the butler's trying to encourage Jack Nicholson to kill his family – to rectify the situation". Jones 2007, 11 or online at <http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2003/mar/31/artsfeatures.turnerprize2003> (15.12.2014). 3 Interview with Richard Prince in Thon – Bodin 2007, 31. -

Fundraiser Catalogue As a Pdf Click Here

RE- Auction Catalogue Published by the Contemporary Art Society Tuesday 11 March 2014 Tobacco Dock, 50 Porters Walk Pennington Street E1W 2SF Previewed on 5 March 2014 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London The Contemporary Art Society is a national charity that encourages an appreciation and understanding of contemporary art in the UK. With the help of our members and supporters we raise funds to purchase works by new artists Contents which we give to museums and public galleries where they are enjoyed by a national audience; we broker significant and rare works of art by Committee List important artists of the twentieth century for Welcome public collections through our networks of Director’s Introduction patrons and private collectors; we establish relationships to commission artworks and promote contemporary art in public spaces; and we devise programmes of displays, artist Live Auction Lots Silent Auction Lots talks and educational events. Since 1910 we have donated over 8,000 works to museums and public Caroline Achaintre Laure Prouvost – Special Edition galleries – from Bacon, Freud, Hepworth and Alice Channer David Austen Moore in their day through to the influential Roger Hiorns Charles Avery artists of our own times – championing new talent, supporting curators, and encouraging Michael Landy Becky Beasley philanthropy and collecting in the UK. Daniel Silver Marcus Coates Caragh Thuring Claudia Comte All funds raised will benefit the charitable Catherine Yass Angela de la Cruz mission of the Contemporary Art Society to -

Quarters Kathryn Tully Compare How the Artists’ Areas in the Two Cities Have Changed Over Time

4 ART AND THE CITY ART TIMES ART DISTRICTS London and New York are the two powerhouses of the international art world, Artist’s supporting galleries, auction houses, museums and, of course, artists. The areas where the latter congregate quickly gain a reputation for style, innovation and creativity – prompting the arrival of dealers and property developers. Based in London and New York respectively, Ben Luke and quarters Kathryn Tully compare how the artists’ areas in the two cities have changed over time LONDON (YBAs), and gathered in a then un- that the character of the place and the It is astonishing that until 2000, when likely crucible for cultural renaissance It is important to try to strike a things that made it successful as an area Tate Modern opened, London lacked – the East End districts of Shoreditch of regeneration can remain in some a national museum of modern art. and Hoxton. balance between ensuring that form, but without stultifying it and Instead, 20th-century art was housed In Lucky Kunst, his memoir of the trying to keep it as a museum.” alongside British art in the Tate Gallery, YBA era, Gregor Muir, now director of the character of the place and the Mirza is particularly focused on now Tate Britain, on Millbank. When it the contemporary gallery Hauser and the area around the 2012 Olympic arrived, Tate Modern shone as a beacon Wirth, remembers arriving as a pen- things that made it successful as an Park. “Hackney Wick has the largest for London’s newfound conviction in niless critic in a Shoreditch suffering concentration of artists anywhere in the kind of art that had long been the from the economic inequalities of the area of regeneration can remain in Europe. -

A Economia Estética Na Moda Contemporânea a Partir Da Passarela De Alexander Mcqueen (1992-2010)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA INSTITUTO DE ARTES E DESIGN - IAD PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTES, CULTURA E LINGUAGENS HENRIQUE GRIMALDI FIGUEREDO ENTRE PADRÕES DE ESTETIZAÇÃO E TIPOLOGIAS ECONÔMICAS: A ECONOMIA ESTÉTICA NA MODA CONTEMPORÂNEA A PARTIR DA PASSARELA DE ALEXANDER MCQUEEN (1992-2010) Juiz de Fora 2018 1 HENRIQUE GRIMALDI FIGUEREDO ENTRE PADRÕES DE ESTETIZAÇÃO E TIPOLOGIAS ECONÔMICAS: A ECONOMIA ESTÉTICA NA MODA CONTEMPORÂNEA A PARTIR DA PASSARELA DE ALEXANDER MCQUEEN (1992-2010) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes, Cultura e Linguagens, área de concentração: Teorias e Processos Poéticos Interdisciplinares, do Instituto de Artes e Design da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof. Dra. Maria Lucia Bueno Ramos Juiz de Fora 2018 2 3 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO DA DISSERTAÇÃO DO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTES, CULTURA E LINGUAGENS Henrique Grimaldi Figueredo Nome do aluno Entre padrões de estetização e tipologias econômicas: a economia estética na moda contemporânea a partir da passarela de Alexander McQueen (1992-2010) Título Prof. Dra. Maria Lucia Bueno Ramos Orientador Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes, Cultura e Linguagens, Área de Concentração: Teorias e Processos Poéticos Interdisciplinares, Linha de pesquisa: Arte, Moda: História e Cultura, da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre. Aprovada em 14/12/2018 Banca Examinadora: ____________________________________________ -

Art Books Spring 2020 Millbank London Sw1p 4Rg

TATE PUBLISHING TATE ENTERPRISES LTD ART BOOKS SPRING 2020 MILLBANK LONDON SW1P 4RG 020 7887 8870 TATE.ORG.UK/PUBLISHING TWITTER: @TATE_PUBLISHING INSTAGRAM: @TATEPUBLISHING CONTENTS NEW TITLES 3 ANDY WARHOL 7 STEVE MCQUEEN 9 BRITISH BAROQUE: POWER AND ILLUSION 11 AUBREY BEARDSLEY 13 A BOOK OF FIFTY DRAWINGS BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY 15 ZANELE MUHOLI 17 LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE 19 MAGDALENA ABAKANOWICZ 21 BRITAIN AND PHOTOGRAPHY: 1945–79 23 HUGUETTE CALAND 25 VENICE WITH TURNER 27 SPRING 29 SUMMER 30 QUENTIN BLAKE: PENS INK & PLACES 31 HOW TO PAINT LIKE TURNER 32 RECENT HIGHLIGHTS 34 BACKLIST TITLES 41 J.M.W. TURNER 42 BARBARA HEPWORTH 43 QUENTIN BLAKE 44 HYUNDAI COMMISSION 45 TATE INTRODUCTIONS 46 MODERN ARTIST SERIES 47 BRITISH ARTIST SERIES 48 REPRESENTATIVES AND AGENTS All profits go to supporting Tate. Please note that all prices, scheduled publication dates and specifications are subject to alteration. Owing to market restrictions some titles are not available in certain markets. For more information on sales and rights contacts see page 48. ANDY WARHOL EDITED BY GREGOR MUIR AND YILMAZ DZIEWIOR NEW TITLES NEW EXHIBITIONS A FASCINATING ‘RE-VISIONING’ OF WARHOL AND Tate Modern HIS UNIQUE VIEW OF AMERICAN CULTURE 12 Mar – 6 Sept 2020 As an underground art star, Andy Warhol (1928–87) Museum Ludwig, was the antidote to the prevalent abstract expressionist Cologne, 10 Oct 2020 style of 1950s America. Looking at his background as – 21 Feb 2021 a child of an immigrant family, his ideas about death and religion, as well as his queer perspective, this Art Gallery of book explores Warhol‘s limitless ambition to push the Ontario, Toronto traditional boundaries of painting, sculpture, film and 27 Mar – 13 Jun 2021 music. -

Alison Wilding

!"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Alison Wilding Born 1948 in Blackburn, United Kingdom Currently lives and works in London Education 1970–73 Royal College of Art, London 1967–70 Ravensbourne College of Art and Design, Bromley, Kent 1966–67 Nottingham College of Art, Nottingham !" L#xin$%on &%'##% London ()* +,-, ./ %#l +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1++.3++0 f24x +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1+.)3+0) info342'5%#564'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om www.42'5%#64'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om !"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Selected solo exhibitions 2013 Alison Wilding, Tate Britain, London, UK Alison Wilding: Deep Water, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Alison Wilding: Drawing, ‘Drone 1–10’, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2011 Alison Wilding: How the Land Lies, New Art Centre, Roche Court Sculpture Park, Salisbury, UK Alison Wilding: Art School Drawings from the 1960s and 1970s, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2010 Alison Wilding: All Cats Are Grey…, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2008 Alison Wilding: Tracking, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2006 Alison Wilding, North House Gallery, Manningtree, UK Alison Wilding: Interruptions, Rupert Wace Ancient Art, London, UK 2005 Alison Wilding: New Drawings, The Drawing Gallery, London, UK Alison Wilding: Sculpture, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, US Alison Wilding: Vanish and Detail, Fred, London, UK 2003 Alison Wilding: Migrant, Peter Pears Gallery and Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh, UK 2002 Alison Wilding: Template Drawings, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2000 Alison Wilding: Contract, The Henry Moore Foundation Studio, Halifax, UK Alison Wilding: New Work, New -

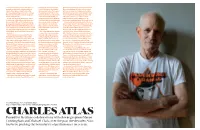

Charles Atlas

The term renaissance man is used rather too short film Ms. Peanut Visits New Atlas also created the 90-minute documentary freely these days, but it certainly applies to York (1999), before directing the Merce Cunningham: a Lifetime of Dance. And Charles Atlas, whose output includes film documentary feature The Legend in 2008, a year before Cunningham died, Atlas directing, lighting design, video art, set design, of Leigh Bowery (2002). The two filmed a production of the choreographer’s ballet live video improvisation, costume design and have remained close collaborators Ocean (inspired by Cunningham’s partner and documentary directing. – Atlas designed the lighting for collaborator John Cage) at the base of the For the past 30 years, Atlas has been best Clark’s production at the Barbican Rainbow Granite Quarry in Minnesota, the known for his collaborations with dancer and – but it was with another legendary performance unfurling against 160ft walls of rock. choreographer Michael Clark, who he began choreographer, who was himself Alongside his better-known works, Atlas has working with as a lighting designer in 1984. His a great influence on Clark, that directed more than 70 other films, fromAs Seen first film with Clark, Hail the New Puritan, was a Atlas came to prominence when on TV, a profile of performance artist Bill Irwin, mock documentary that followed dance’s punk he first mixed video and dance in to Put Blood in the Music, his homage to the renegade as his company, aided by performance the mid-1970s. diversity of New York’s downtown music scene artist Leigh Bowery and friends, prepared for Merce Cunningham was already of the late 1980s. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

Courtauld East Wing Biennial

ARTIFICIAL REALITIES 30 January 2016 - 30 June 2017 Jacob Hashimoto, Gossamer Cloud, 2006, Paper, bamboo, dacron, acrylic colours,Courtesy of Studio la Città, Verona. Photographer: © Michele Alberto Seren • The East Wing Biennial committee of The Courtauld Institute of Art is pleased to present ‘Artificial Realities’, the twelfth instalment of contemporary art which occupies the working Institute of Art • 31 international exhibitors, including Tracey Emin, Antony Gormley and Rachel Whiteread, have been selected by a student committee to engage with a curatorial theme • The selection of works by both established and emerging artists will challenge and expose “ingrained” realities through highlighting the dynamic relationship between the real and the virtual • PRIVATE VIEW: Friday 29 January 2016, 7:30 - 10:00pm, The Courtauld Institute of Art, Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN (guest list only) • For further information and press images, please contact Evy Cauldwell French on [email protected] Founded by Art Impresario Joshua Compston in 1991, the East Wing Biennial will return to promote contemporary art within The Courtauld Institute of Art at Somerset House in early 2016. The 18-month exhibition Artificial Realities, will feature works by 31 international artists, including Tracey Emin, Antony Gormley, Jacob Hashimoto, Rachel Whiteread, Jim Lambie and Laure Prouvost. Artificial Realities takes the viewer through the spaces of the Courtauld Institute, where the works of art gesture towards the transition from the real to illusion, truth to fiction, and the ambiguous borders between the two. The works themselves are experienced through the transitional spaces and minor rooms of the Courtauld, revealing traces and layers of perception by interfering with the daily experience of the Institute’s inhabitants, and confronting the viewer with the uncanny.