Article Beyond Apartheid: Race, Transformation and Governance In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sadd Confident Against Ahli

FOOTBALL | Page 2 CCRICKETRICKET | Page 10 Young stars Pakistan To Advertise here Call: 444 11 300, 444 66 621 arrive in Doha launches high for Al Kass octane T20 International league in UAE Thursday, February 4, 2016 LADIES TOUR OF QATAR Rabia II 25, 1437 AH Garfoot takes GULF TIMES second stage; Wild crashes SPORT Page 11 FOCUS Federer out for month aft er knee surgery AFP four-set defeat by eventual winner Novak Basel Djokovic in the Australian Open semi-fi - nals, going down 6-1, 6-2, 3-6, 6-3, in his eighth loss to the Serb in their last 10 Grand eventeen-time Grand Slam winner Slam meetings. Roger Federer underwent “success- Federer hasn’t beaten the runaway world ful” surgery on his knee yesterday number one at a major since the Wimble- and will be ruled out of action for don semi-fi nals in 2012, when he last won a Sone month, his agent said. Grand Slam title. Federer underwent the surgery to repair Unlike great rival Rafael Nadal, Federer has a torn meniscus sustained the day after his enjoyed a relatively injury-free career, the ex- semi-fi nal match at the Australian Open, ception being bouts of recurring back pain. according to Tony Godsick. The last time that happened was at the As a result of the surgery, Federer will 2014 ATP World Tour Finals in London now miss the ATP tournaments in Rotter- when he withdrew at the last minute from dam and Dubai this month. the fi nal against Djokovic. -

Annual Report 2007 08 Index

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 08 INDEX VISION & MISSION 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 4 CEO REPORT 6 AMATEUR CRICKET 12 WOMEN’S CRICKET 16 COACHING & HIGH PERFORMANCE 18 DOMESTIC PROFESSIONAL CRICKET 22 DOMESTIC CRICKET STATS 24 PROTEAS’ REPORT 26 SA INTERNATIONAL MILESTONES 28 2008 MUTUAL & FEDERAL SA CRICKET AWARDS 30 COMMERCIAL & MARKETING 32 CRICKET OPERATIONS 36 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 40 GENERAL COUNCIL 42 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 43 TREASURER’S REPORT 44 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 46 UNITED CRICKET BOARD OF SOUTH AFRICA 62 CRICKET SOUTH AFRICA (PROPRIETARY) LIMITED 78 1 VISION & MISSION VISION Cricket South Africa’s vision is to make cricket a truly national sport of winners. This has two elements to it: • To ensure that cricket is supported by the majority of South Africans, and available to all who want to play it • To pursue excellence at all levels of the game MISSION As the governing body of cricket in South Africa, Cricket South Africa will be lead by: • Promoting and protecting the game and its unique spirit in the context of a democratic South Africa. • Basing our activities on fairness, which includes inclusivity and non-discrimination • Accepting South Africa’s diversity as a strength • Delivering outstanding, memorable events • Providing excellent service to Affiliates, Associates and Stakeholders • Optimising commercials rights and properties on behalf of its Affiliates and Associates • Implementing good governance based on King 2, and matching diligence, honesty and transparency to all our activities CODE -

CSA Schools T20 Challenge 2 Pretoria | 6-8 March 2020 Messages

Messages Previous Winners Umpires Emergency Contacts Daily Programme Fixtures NATIONAL CRICKET WEEK POOL A | Team Lists POOL B | Team Lists Playing Conditions CSA SCHOOLS T20 Procedure for the Super Over T20 CHALLENGE Appendix 1 Pretoria | 6-8 March 2020 Appendix 2 Schools Code of Conduct Messages Chris Nenzani | President, Cricket South Africa Previous Winners Umpires The Schools’ T20 tournament CSA values our investment in youth extremely highly. It is is not just the biggest event an important contribution to nation building through cultural Emergency Contacts that Cricket South Africa (CSA) diversity which has become one of the pillars on which our has ever handled but it creates cricket is built. CSA has travelled a wonderful journey over the Daily Programme a pathway of opportunity for past 29 years of unity and everybody can be proud of his or her schools at all levels to live their contribution. dreams. Fixtures There are countless cricketers who have gone on from our It takes the game to every corner youth programs to engrave their names with distinction in South of the country and to established African cricket history and we congratulate them and thank them POOL A | Team Lists cricket schools as well as those that are just starting to make for their contributions. their way. As such it is a key component of our development POOL B | Team Lists program and of our vision and commitment to take the game to I must also put on record our thanks to all the people who have given up their time without reward to coach and mentor our all. -

Leicester to Off Er Mega-Fl Ops As Mahrez New Deal but Chinese Teams Crash out AFP Shake-Up Last Month, Report- Shanghai Edly Because of Their Struggles in Asia

NBA | Page 6 CRICKET | Page 9 Cavs take Rahane long-range powers approach Pune to to big win 7-wkt win Friday, May 6, 2016 TENNIS Rajab 29, 1437 AH Murray dominates GULF TIMES Simon to reach Madrid quarters SPORT Page 8 US sprinters Tori Bowie (L), Veronica Campbell-Brown and Dutch Dafne Schippers (C) at the Museum of Islamic Art IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE DOHA LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION As many as 11 reigning world champions lead a field of 80 global medallists who will embark on the road to achieve their 2016 Olympic aspirations, starting with today’s Diamond League meeting By Satya Rath Qatar Athletics Federation president events. After equalling his own 9.91 for the fi rst time, an appearance she’s Doha Dahlan al-Hamad echoed Coe’s senti- Asian record in the 100m last month eagerly anticipating. “I’ve heard that ments: “We have set high standards in in Florida, the fastest timing in 100m it’s a very nice track, and it’s very nice organising important and prestigious this year, Femi Ogunode will be among to be able to compete against these very t’s that time of the year again, as it sporting events in previous years and the favourites in the men’s 200m. He is fast women,” Schippers said. has been for the last six years. we aim to continue at the highest pos- also the Asian record holder in the 200 One of those “fast women” she’ll be The opening leg of the IAAF sible level. As this is the Olympic year, at 19.97. -

2009-2010 CSA Annual Report and Financial Statement

TOMORROW SHAPING 2 0 0 9 / 1 0 REPORT A N N UA L CRICKET SOUTH AFRICA ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 0 9 / 1 0 SHAPING TOMORROW Shaping Tomorrow We live in the most exciting era of sporting development. A time when full contact sport no longer holds centre stage. It is a passage of time when the art of sport is appreciated over the physicality of competition. Today, latent skills and blossoming talent has a place amongst our youth and the generations to come. It is now the subtle brilliance of deftness, the art of touch, mastery of stroke and pure strategic guile that has turned cricket into the sport of the future. Today cricket is the stage for mental agility and peak physical condition. It is purity of both mind and spirit that produces champions. The re-invention of cricket globally has rejuvenated a desire to master the ultimate game. A sense of camaraderie pursued by both men and women alike. It’s now a passion for gamesmanship, integrity, honesty and fair play. It is a game that can be embraced and played or supported by everyone. We can’t undo the past, but we can shape the future. We do what we do today in cricket, for what will happen TOMORROW. ConTEnTS 4 Vision and Mission 5 Ten Thrusts to Direct Transformation of Cricket in South Africa 6 President’s Message 8 CEO’s Report 18 Mapping the Way Forward 20 Reviving the CSA Presidential Plan 22 Black African Cricket on the Rise 24 KFC Mini Cricket gets Bigger and Better 26 Youth Cricket: Uplifting the Faces of Tomorrow 28 Under-19 Cricket gives Young Stars the Platform to Shine 30 First-Class -

Sport Awards 2015 Foreword

Sport Awards 2015 Foreword The annual Sports Awards is a highlight of the Western Cape Government’s calendar. The Awards recognise and officially acknowledge the esteemed excellence of sportspeople hailing from the Western Cape. Today, we pay tribute to the exemplary role these individuals have played in the development of sport and motivating others to achieve more. I wholeheartedly thank each sportsperson awarded their prestigious acknowledgement for serving as a beacon of hope to all in the Western Cape. Their perseverance, focus and positive choices have groomed them into significant role-models to whom youth can aspire. Excellence in their respective sporting codes requires dedication, motivation and many hours of practice, but also most importantly support and encouragement from significant others: family, friends, coaches, managers and others. Heartfelt gratitude is expressed to them for their continuous support and encouragement toward our sporting success. Sport Awards 1 History has shown time and again that sport has the ability to bring diverse groups of people together and I fi rmly believe our honoured sport stars personify this notion. They also promote a healthy lifestyle in which they contribute to increasing wellness and safety in the Western Cape and for that I thank you profusely. By celebrating our victories and achievements we create a spirit of goodwill and social inclusivity that ultimately binds us all better together. In closing, a special word of thanks to all the DCAS team players for your hard work, dedication and professionalism in making the Sports Awards a proud occasion. Anroux Marais Minister of Cultural Affairs and Sport Western Cape Government 2 Sport Awards Volunteer Of The Year Mogamat Yassiem Khan – Western Province Fancy Pigeons Yassiem puts in long hours to ensure administrative compliance and that all shows are a success. -

Inauguralimperial Central Gauteng Lions Women Invitational Golf

INAUGURAL IMPERIAL DATE 27 November CENTRAL GAUTENG LIONS WOMEN 2020 INVITATIONAL GOLF DAY START TIME 11am VENUE Country Club, Johannesburg, Woodmead, Rocklands Course FORMAT Stableford SPECIAL GUESTS Imperial Central Gauteng Lions Women WOMEN Cricket Team IN SUPPORT OF RAISING AWARENESS OF THE HIGH LEVELS OF FEMICIDE The Imperial Central Gauteng Lions Women cricket team is hosting its Inaugural Imperial Central Gauteng Lions Women Annual Invitational Golf Day We have packaged various sponsorships and partnership opportunities that fits any budget including but not limited to: Associate partners – Silver and Bronze Golf shirt, Cap and Golf Balls sponsor Beverage sponsor Prize give away partners – Overall winner, 2nd & 3rd place, Longest drive and closest to the pin sponsor Dinner sponsor Hole sponsorship Only 4-ball Hole sponsorship + 4 ball For more information contact: Zethu Kaka | 083 455 9550 | [email protected] INAUGURAL IMPERIAL CENTRAL GAUTENG LIONS WOMEN INVITATIONAL GOLF DAY SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Bronze Own Four Hole Sponsor Own 4-ball & Golf Shirt Prize Longest Drive Closest to the Pin RIGHTS Silver Package Package Ball & no 4-ball Hole Sponsor Sponsor Golf Cap Sponsor Dinner Sponsor Sponsor (Ladies & Men) (Ladies & Men) Total Grouping # of Sponsors (Max) 1 1 1 1 1 5 4 4 Exclusive (Y/N) Y Y Y N N N N Y Y Y N INVESTMENT Cash Investment (Ex Vat) R50 000 R25 000 R6 000 R5 000 R10 000 0 0 R50 000 0 0 0 R146 000 Investment In Kind VIK (Ex Vat) 0 0 0 0 0 R40 000 R10 000 R2 500 R2 500 R2 500 R2 500 R50 000 ELIGIBLE ELEMENT Official Sponsor Status Y Y N N N Y Y Y N N N 0 Naming Rights N N N N N N N N N N N 0 # Of advertising perimeter boards at the imperial wanderes stadium during the 2020/2021 imperial lions season games only (spec chromodek boards 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 4 1000mm x5000mm). -

ICC Annual Report 2003-04 3 2003-04 Annual Report

2003-2004 Annual Report & Accounts Mission Statement ‘As the international governing body for cricket, the International Cricket Council will lead by promoting the game as a global sport, protecting the spirit of cricket and optimising commercial opportunities for the benefit of the game.’ ICC Annual Report 2003-04 3 2003-04 Annual Report & Accounts Contents 2 President’s Report 32 Integrity, Ethical Standards and Ehsan Mani Anti-Corruption 6 Chief Executive’s Review Malcolm Speed 36 Cricket Operations 9 Governance and 41 Development Organisational Effectiveness 47 Communication and Stakeholders 17 International Cricket 18 ICC Test Championship 51 Business of Cricket 20 ICC ODI Championship 57 Directors’ Report and Consolidated 22 ICC U/19 Cricket World Cup Financial Statements Bangladesh 2004 26 ICC Six Nations Challenge UAE 2004 28 Cricket Milestones 35 28 21 23 42 ICC Annual Report 2003-04 1 President’s Report Ehsan Mani My association with the ICC began in 1989 Cricket is an international game with a Cricket Development and over the last 15 years, I have seen the multi-national character. The Board of the ICC The sport’s horizons continue to expand with organisation evolve from being a small, is comprised of the Chairmen and Presidents China expected to be one of the countries under-resourced and reactive body to one of our Full Member countries as well as applying to take our total membership above that is properly resourced with a full-time representatives of our Associate Members. 90 countries in June. professional administration that leads the This allows for the views of all Members to We are conscious that the expansion of game in an authoritative manner for the be considered in the decision-making process. -

Sport Consumption Patterns in the Eastern Cape:Cricket

SPORT CONSUMPTION PATTERNS IN THE EASTERN CAPE: CRICKET SPECTATORS AS SPORTING UNIVORES OR OMNIVORES Kelcey Brock* Gavin Fraser# Rhodes University Rhodes University Ferdi Botha+ Rhodes University Received: March 2016 Accepted: July 2016 Abstract Since its inception, consumption behaviour theory has developed to account for the important social aspects that underpin or at least to some extent explain consumer behaviour. Empirical studies on consumption behaviour of cultural activities, entertainment and sport have used Bourdieu’s (1984) omnivore/univore theory to investigate consumption of leisure activities. The aim of this study is to investigate whether South African cricket spectators are sporting omnivores or univores. The study was conducted among cricket spectators in the Eastern Cape at four limited overs cricket matches in the 2012/2013 cricket season. The results indicate that consumption behaviour of sport predominantly differs on the grounds of education and race. This suggests that there are aspects of social connotations underpinning sports consumption behaviour within South Africa. Keywords Consumption; sport; univores; omnivores; social connotations _______________________________ *Ms K Brock is a lecturer in the Department of Economics and Economic History, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. #Prof G Fraser is professor in the Department of Economics and Economic History, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. +Mr F Botha is a senior lecturer in the Department of Economics and Economic History, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. [[email protected]] Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences | JEF | October 2016 9(3), pp. 667-684 667 Brock, Fraser & Botha 1. INTRODUCTION Sport is highly regarded among South Africans, both in terms of active participation and in a passive role as a spectator (Brember, 2009). -

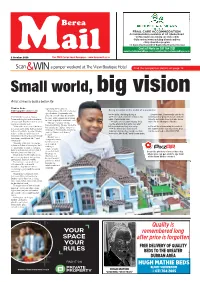

Your Space Your Rules

2 October 2020 Your FREE Caxton Local Newspaper - www.bereamail.co.za Scan& WIN a pamper weekend at The View Boutique Hotel Find the competition details on page 12 Artist strives to build a better life Thabiso Goba depending on the project. [email protected] Depending on the size and design Being an artist in the midst of a pandemic specifi cations, Gwamanda said AsA anan artist, working during a Despite that, Gwamanda said he is projects can take days to complete YOUNG Durban artist, Qiniso papandemicnde and economic crisis is not running out of projects to sell and will because of the amount of attention Gwamanda (right), makes miniature eaeeasy,syy, GGwamanda said. have to set aside time to make some to detail required in miniature craft. art for people who want to recreate a "P"PeoplePeoe are reluctant to pay, they more for the Musgrave Market. "No one was interested in world at a smaller scale. lilikeke thethehe artwork, but once you start Pietermaritzburg. No one wanted to "Most of the time people want me tatalkinglkking numbers they run away z He will be showcasing his work at buy or help me. All the doors were to recreate something that's personal bebecausecau there are much more the market in the coming weeks and shutting, so I eventually decided to to them. It could be a pastor wanting imimportantmpoort things they could use their can be reached at 064 074 8795. come to Durban in February," to have a church replica or a new momoneynen y for, like food," said Gwamanda. -

Cricket, Culture, and Society in South Africa

Bruce Murray, Christopher Merrett. Caught Behind: Race and Politics in Springbok Cricket. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2004. xiv + 256 pp. $28.50, paper, ISBN 978-1-86914-059-5. Reviewed by Goolam Vahed Published on H-SAfrica (May, 2005) Until 1990, the literature on South African South Africa (UCB). Tensions around race, merit, cricket focused primarily on White cricket.[1] This and transformation resulted in the UCB adopting reflected not only White political, social, and eco‐ a Transformation Charter in 1999 to address re‐ nomic dominance, but also the fact that only dress and representation, and establish a culture Whites were seen to constitute the "nation" and of non-racialism. The Charter called for the histo‐ represented South Africa in international compe‐ ry of Black cricket to be recorded to heal the "psy‐ tition. The advent of non-racial democracy chological" wounds of Black cricketers, and "make changed this. During the apartheid years, most known the icons from communities previously historians of South Africa focused on resistance neglected." KwaZulu Natal, Western Cape, and politics, racial consciousness, and class formation. Gauteng have already completed their histories. South African historiography has become more [2] There has simultaneously been a surge in gen‐ diverse since the end of apartheid, with scholars eral works on the politics of sport in South Africa. turning their attention to the history of sport, en‐ [3] vironment, science, technology, culture, educa‐ The latest addition to this historiography, tion, and so on. This shift from a White ethnocen‐ Caught Behind, falls into the latter genre. It pro‐ tric approach is advancing our knowledge of the vides an excellent synthesis of the politics of previously neglected histories of Black South South African cricket from the origins of the game Africans. -

Organised Crime on the Cape Flats 35

Andre Standing i Organised crime A study from the Cape Flats BY ANDRE STANDING This publication was made possible through the generous funding of the Open Sociey Foundation i ii Contents www.issafrica.org @ 2006, Institute for Security Studies All rights reserved Copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Institute for Security Studies, and no part may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both the author and the publishers. The opinions expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Trustees, members of the ISS Council, or donors. Authors contribute to ISS publications in their personal capacity. ISBN: 1-920114-09-2 First published by the Institute for Security Studies PO Box 1787, Brooklyn Square 0075 Pretoria, South Africa Cover photo: Benny Gool/Oryx Media Productions/africanpictures.net Cover: Page Arts cc Printers: Tandym Print Andre Standing iii Acknowledgements This book was commissioned by the Institute for Security Studies through a grant provided by the Open Society Foundation. I have been fortunate to work from the Cape Town office of the ISS for the past few years. The director of the ISS in Cape Town, Peter Gastrow, has been exceptionally supportive and, dare I say it, patient in waiting for the final publication. Friends and colleagues at the ISS who have helped provide a warm and stimulating work environment include Nobuntu Mtwa, Pilisa Gaushe, Charles Goredema, Annette Hubschle, Trucia Reddy, Andile Sokomani, Mpho Mashaba, Nozuko Maphazi and Hennie van Vuuren. In writing this book I have been extremely fortunate to have help and guidance from John Lea, who I owe much to over the years.