FAMILY, ANCESTRY, IDENTITY, SOCIAL NORMS Marina Tan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009, and Electronic Visits Rose to About 6 Million, an Increase of 12 Percent from the Previous Year

Message from Chairman and Chief Executive The year in review was a period of significant achievements for the National Library Board (NLB). Book and audiovisual loans registered a new record of close to 31 million, about 11 percent increase from FY2008/2009, and electronic visits rose to about 6 million, an increase of 12 percent from the previous year. The number of electronic retrievals last year was about 48 million, a tremendous 72 percent more than the previous year. The record levels of library use demonstrated the enduring value of our libraries to lifelong learning. Over the past year, while grappling with the challenges of an economic downturn, Singaporeans continued to turn to our libraries as trusted sources of knowledge and information that would help them gain new insights, seize opportunities and achieve their aspirations. On another level, the rising importance of our libraries is heartening proof that our progress towards Library 2010 (L2010) has had a meaningful impact on the lives of Singaporeans in this digital age. L2010 is the strategic roadmap to build a seamless 24/7 library system leveraging diverse digital and physical delivery channels. In the past year, we continued to enhance our collections and expand our patrons’ access to both traditional and digital content. At the same time, we strived to meet the diverse needs of our patrons with a broad range of programmes and service initiatives. Developing and Ensuring Access to Our Collections Good collections and access to them are fundamental to the quality of knowledge that our libraries offer. In the year in review, we continued to enhance and refresh our print, digital and documentary materials through donations, acquisitions and digitisation. -

China 17 10 27 Founder Series

CHINA Exploring Ancient and Modern China with Master Chungliang “Al” Huang Dates: October 27 – November 7, 2017 Cost: $6,995 (Double Occupancy) A Cross Cultural Journeys Founders Series with Carole Angermeir and Wilford Welch !1 ! ! ! Daily Itinerary This trip is for those who want to understand the ancient cultural traditions from which modern China has emerged. It is for those who want to experience China with a world- renowned teacher with deep knowledge and insights who has for decades become well known throughout the West for his expertise in Chinese culture and who gracefully and knowledgeably embraces both cultures. Our small group will meet in Shanghai on October the 27th, 2017 and travel on to two of the most beautiful and ancient of all Chinese cities, Hangzhou and Suzhou. Hangzhou is the city where our leader, Chungliang “Al” Huang spent many of his early years. We will be honored to stay there in the Xin Xin hotel that was once his family’s home. Each morning we will join Al in Tai Chi, the ancient, gentle Chinese exercise, dance, and meditation form. Over the course of the next ten days, we will develop, through Al’s knowledge, insights, and contacts, an understanding of the Chinese people and culture. We will have personal visits to Chinese calligraphers and musicians; learn about China’s rich history, poetry and mythic story telling and how these are all woven into the fabric of modern China today. Al is credited by many with introducing Tai Chi to the West in the 1970s. He is also recognized in China for the role he played in reintroducing Tai Chi back to China in the 1980s, after it had been rejected during the Cultural Revolution. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

LEE KONG CHIAN RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP the National Library

LEE KONG CHIAN RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP The National Library of Singapore invites applications for the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship programme, a six-month residential fellowship to research valuable historical materials, dating from the 16th century, on Singapore and Southeast Asia in the collections of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and the National Archives of Singapore. Besides historical materials from the Gibson-Hill Collection, Ya Yin Kwan (or Palm Shade Pavilion) Collection, Logan Collection, Rost Collection as well as the former Raffles Library Collection, the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library also holds significant and early works documenting the history of Singapore and the region, which include imprints from Singapore’s earliest printing presses, early European accounts of Southeast Asia, early maps and charts of the region and archives of prominent Singapore authors. The National Archives of Singapore holds records of national or historical significance acquired from public agencies, private sources and overseas institutions and archives. The Library welcomes applications from curators, historians, academics or independent researchers with established records of achievement in their chosen fields of research. Scholars pursuing doctoral, postdoctoral or advanced research are also encouraged to apply. Recipients are expected to remain in residence at the library, located in the central district of Singapore, during the period of their fellowship and to focus their time on researching the collections in the Lee Kong Chian -

Chinese at Home : Or, the Man of Tong and His Land

THE CHINESE AT HOME J. DYER BALL M.R.A.S. ^0f Vvc.' APR 9 1912 A. Jt'f, & £#f?r;CAL D'visioo DS72.I Section .e> \% Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/chineseathomeorm00ball_0 THE CHINESE AT HOME >Di TSZ YANC. THE IN ROCK ORPHAN LITTLE THE ) THE CHINESE AT HOME OR THE MAN OF TONG AND HIS LAND l By BALL, i.s.o., m.r.a.s. J. DYER M. CHINA BK.K.A.S., ETC. Hong- Kong Civil Service ( retired AUTHOR OF “THINGS CHINESE,” “THE CELESTIAL AND HIS RELIGION FLEMING H. REYELL COMPANY NEW YORK. CHICAGO. TORONTO 1912 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE . Xi CHAPTER I. THE MIDDLE KINGDOM . .1 II. THE BLACK-HAIRED RACE . .12 III. THE LIFE OF A DEAD CHINAMAN . 21 “ ” IV. T 2 WIND AND WATER, OR FUNG-SHUI > V. THE MUCH-MARRIED CHINAMAN . -45 VI. JOHN CHINAMAN ABROAD . 6 1 . vii. john chinaman’s little ones . 72 VIII. THE PAST OF JOHN CHINAMAN . .86 IX. THE MANDARIN . -99 X. LAW AND ORDER . Il6 XI. THE DIVERSE TONGUES OF JOHN CHINAMAN . 129 XII. THE DRUG : FOREIGN DIRT . 144 XIII. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN EATS AND DRINKS . 158 XIV. JOHN CHINAMAN’S DOCTORS . 172 XV. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN READS . 185 vii Contents CHAPTER PAGE XVI. JOHN CHINAMAN AFLOAT • 199 XVII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN TRAVELS ON LAND 2X2 XVIII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN DRESSES 225 XIX. THE CARE OF THE MINUTE 239 XX. THE YELLOW PERIL 252 XXI. JOHN CHINAMAN AT SCHOOL 262 XXII. JOHN CHINAMAN OUT OF DOORS 279 XXIII. JOHN CHINAMAN INDOORS 297 XXIV. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

1 参考资料list of References 阿窿ā Lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽

参考资料 List of References 阿窿 ā lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽子凡(2008)。香港粤语惯用语研究。香港城市大学出版社。 吴昊(2006)。港式广府话研究(1)。次文化堂出版社。 Chan, K. S. (2005). One more story to tell: Memories of Singapore, 1930s-1980s. Landmark Books. Geisst, C. R. (2017). Loan sharks: The birth of predatory lending. Brookings Institution Press. Iskandar, T. (2005). Kamus dewan edisi keempat. Dewan Bahasa Dan Pustaka. 爱它死 ài tā sǐ 周清海(2002)。新加坡华语词与语法。玲子传媒私人有限公司。 Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Drugs and inhalants. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/drugs-and-inhalants. Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Misuse of Drugs Act. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/misuse-of-drugs-act. Holland, J. (2001). Ecstasy: The complete guide: A comprehensive look at the risks and benefits of MDMA. Park Street Press. Lee, T. K., et al. (1998). A 10-year review of drug seizures in Singapore. Medicine, Science and the Law, 38(4), 311-316. National Archives of Singapore. (1997). Keynote address by Mr Wong Kan Seng. Minister for Home Affairs at the 1997 National Seminar on drug abuse at Shangri-La Hotel. Retrieved on 16 October 2019: www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/1997040502/wks19970405s.pdf. 按柜金 àn guì jīn 邓贵华(2015 年 8 月 26 日)。较上届大选少约 10% 候选人竞选按柜金 1 万 4500 元。 联合早报。Retrieved on 12 September 2019: https://www.zaobao.com.sg/zpolitics/news/story20150826-518789. 湖南法制院(1912)、湖南调查局编(1911 年)、劳柏文校(清)。湖南民情风俗报 告书:湖南商事习惯报告书。湖南教育出版社,2010。 汪惠迪(1999)。时代新加坡特有词语词典。联邦出版社。 Elections Department. (2011). Parliamentary Elections Act (Chapter 218). -

1 Contemporary Ethnic Identity of Muslim Descendants Along The

1 Contemporary Ethnic Identity Of Muslim Descendants Along the Chinese Maritime Silk Route Dru C Gladney Anthropology Department University of South Carolina U.S.A At the end of five day's journey, you arrive at the noble-and handsome city of Zaitun [Quanzhoui] which has a port on the sea-coast celebrated for the resort of shipping, loaded with merchandise, that is afterwards distributed through every part of the province .... It is indeed impossible to convey an idea of the concourse of merchants and the accumulation of goods, in this which is held to be one of the largest and most commodious ports in the world. Marco Polo In February 1940, representatives from the China Muslim National Salvation society in Beijing came to the fabled maritime Silk Road city of Quanzhou, Fujian, known to Marco Polo as Zaitun, in order to interview the members of a lineage surnamed "Ding" who resided then and now in Chendai Township, Jinjiang County. In response to a question on his ethnic background, Mr. Ding Deqian answered: "We are Muslims [Huijiao reo], our ancestors were Muslims" (Zhang 1940:1). It was not until 1979, however, that these Muslims became minzu, an ethnic nationality. After attempting to convince the State for years that they belonged to the Hui nationality, they were eventually accepted. The story of the late recognition of the members of the Ding lineage in Chendai Town and the resurgence of their ethnoreligious identity as Hui and as Muslims is a fascinating reminder that there still exist remnants of the ancient connections between Quanzhou and the Western Regions, the origin points of the Silk Road. -

Title Freshwater Fishes, Terrestrial Herpetofauna and Mammals of Pulau Tekong, Singapore Author(S) Kelvin K.P

Title Freshwater fishes, terrestrial herpetofauna and mammals of Pulau Tekong, Singapore Author(s) Kelvin K.P. Lim, Marcus A. H., Chua and Norman T-L. Lim Source Nature in Singapore, 9, 165–198 Published by Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore Copyright © 2016 National University of Singapore This document may be used for private study or research purpose only. This document or any part of it may not be duplicated and/or distributed without permission of the copyright owner. The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. This document first appeared in: Lim, K. K. P., Chua, M. A. H., & Lim, N. T. -L. (2016). Freshwater fishes, terrestrial herpetofauna and mammals of Pulau Tekong, Singapore. Nature in Singapore, 9, 165–198. Retrieved from http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/nus/images/pdfs/nis/2016/2016nis165-198.pdf This document was archived with permission from the copyright owner. NATURE IN SINGAPORE 2016 9: 165–198 Date of Publication: 1 November 2016 © National University of Singapore Freshwater fishes, terrestrial herpetofauna and mammals of Pulau Tekong, Singapore Kelvin K.P. Lim1*, Marcus A. H. Chua1 & Norman T-L. Lim2 1Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117377, Republic of Singapore; Email: [email protected] (KKPL; *corresponding author), [email protected] (MAHC) 2Natural Sciences and Science Education Academic Group, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616, Republic of Singapore; Email: [email protected] (NTLL) Abstract. The diversity of terrestrial and freshwater, non-avian, vertebrate fauna of Pulau Tekong, an island used almost exclusively by the Singapore Armed Forces, was compiled. -

Portrayals of an Overseas Chinese Tycoon in Southeast Asia

BEYOND REPRESENTATION ? PORTRAYALS OF AN OVERSEAS CHINESE TYCOON IN SOUTHEAST ASIA HUANG Jianli, PhD Department of History National University of Singapore Email: [email protected] (2011 Lee Kong Chian NUS-Stanford Distinguished Fellow on Southeast Asia) 26 April 2011, Tuesday, 12-1.30 pm [***Presentation based partly upon journal article: Huang Jianli, ‘Shifting Culture and Identity: Three Portraits of Singapore Entrepreneur Lee Kong Chian’, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 82.1 (Jun 2009): 71-100] 1 PRELIMINARIES • Gensis of project on ‘Lee Kong Chian 李光前 & His Economic Empire’ – A most impt Ch entrepr in Ch diaporic landscape fr 1920s~1960s – OC story of rags to riches, econ empire over Spore-Malaya(sia)-Indonesia – Shock discovery on extant writings: almost solely Ch-lang pubns + repetitive • Thrust of today’s seminar: Beyond Representation ??? – Part I: Representational analysis as core Ø Historiographical but aim at revealing cultural & identity politics Ø Surmising 3 portrayals v A leading capitalist & philanthropist in Nanyang v A representative patriot of the Ch diaspora v A local ‘Virtuous Pioneer’ 先贤 in revised Spore history template – Part II: Moving beyond representation Ø Limitations of representation-portrayal Ø Current lines of empirical exploration • Introducing the man (1893-1967) – Migrated 1903, age 10 fr Furong 芙蓉– Nan’an 南安 – Fujia福建 to Spore – Back to Ch for edn 1908-1912 & return as sch teacher, translator, surveyor – With tycoon Tan Kah Kee 陈嘉庚, married daughter, started own biz 1928 – Built up empire in Grt Depr & Korean War, retired 1954, died @ age 74 – Still legacy & big impact today thro’ Lee Foundation 2 A. -

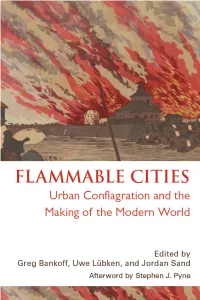

Flammable Cities: Urban Conflagration and the Making of The

F C Flammable Cities Urban Conflagration and the Making of the Modern World Edited by G B U L¨ J S T U W P Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the German Historical Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society at LMU Munich, Germany. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711–2059 uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2012 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flammable cities: Urban conflagration and the making of the modern world / edited by Greg Bankoff, Uwe Lübken, and Jordan Sand. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-299-28384-1 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-299-28383-4 (e-book) 1. Fires. 2. Fires—History. I. Bankoff, Greg. II. Lübken, Uwe. III. Sand, Jordan. TH9448.F59 2012 363.3709—dc22 2011011572 C Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 P : C F R 1 Jan van der Heyden and the Origins of Modern Firefighting: Art and Technology in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam 23 S D K 2 Governance, Arson, and Firefighting in Edo, 1600–1868 44 J S and S W 3 Taming Fire in Valparaíso, Chile, 1840s–1870s 63 S J. -

Balestier Heritage Trail Booklet

BALESTIER HERITAGE TRAIL A COMPANION GUIDE DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE OTHER HERITAGE TRAILS IN THIS SERIES ANG MO KIO ORCHARD BEDOK QUEENSTOWN BUKIT TIMAH SINGAPORE RIVER WALK JALAN BESAR TAMPINES JUBILEE WALK TIONG BAHRU JURONG TOA PAYOH KAMPONG GLAM WORLD WAR II LITTLE INDIA YISHUN-SEMBAWANG 1 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Healthcare and Hospitals 45 Tan Tock Seng Hospital Early History 3 Middleton Hospital (now Development and agriculture Communicable Disease Centre) Joseph Balestier, the first Former nurses’ quarters (now American Consul to Singapore Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine) Dover Park Hospice After Balestier 9 Ren Ci Community Hospital Balestier Road in the late 1800s Former School Dental Clinic Country bungalows Handicaps Welfare Association Homes at Ah Hood Road Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital Tai Gin Road and the Sun Yat The National Kidney Foundation Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall Eurasian enclave and Kampong Houses of Faith 56 Chia Heng Goh Chor Tua Pek Kong Temple Shophouses and terrace houses Thong Teck Sian Tong Lian Sin Sia Former industries Chan Chor Min Tong and other former zhaitang Living in Balestier 24 Leng Ern Jee Temple SIT’s first housing estate at Fu Hup Thong Fook Tak Kong Lorong Limau Maha Sasanaramsi Burmese Whampoe Estate, Rayman Buddhist Temple Estate and St Michael’s Estate Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi The HDB era Kebun Limau Other developments in the Church of St Alphonsus 1970s and 1980s (Novena Church) Schools Seventh-Day Adventist Church Law enforcement Salvation Army Balestier Corps Faith Assembly of God Clubs and