What Do Private Equity Transactions Tell Us About Optimal Capital Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leadership Newsletter Winter 2020 / 2021

T���������, M���� ��� T����������������� Leadership Newsletter Winter 2020 / 2021 GTCR Firm Update Since the firm’s inception in 1980, GTCR has Technology, Media and Tele- partnered with management teams in more communications than 200 investments to build and transform growth businesses. Over the last twenty years alone, GTCR has invested over $16 billion in approximately 100 platform acquisitions, 30+ 95+ PLATFORMS ADD-ONS including more than 65 companies that have been sold for aggregate enterprise value of over $ $50 billion and another 14 companies that have 25B+ been taken public with aggregate enterprise value PURCHASE of more than $34 billion. In November 2020, PRICE we closed GTCR Fund XIII, the firm’s largest fund to date, with $7.5 billion of limited partner capital commitments. This fund follows GTCR Fund Acquisition Activity Since 2000 XII, which we raised in 2017, with $5.25 billion As of January 15, 2021* of limited partner capital commitments. GTCR currently has 25 active portfolio companies; ten of these companies are within the Technology, Media and Telecommunications (“TMT”) industry. Page 1 / Continues on next page Technology, Media and Telecommunications Group Update Since 2000, GTCR has completed over 30 new platform investments and over 95 add-on acquisitions within the TMT industry, for a total of over 125 transactions with a combined purchase price of over $25 billion. During just the past year, we have realized several of these investments, selling three businesses and completing the partial sale of two additional companies, for a combined enterprise value of over $9 billion. Our TMT franchise includes ten active portfolio companies and one management start-up, which together have completed nearly 30 add-on acquisitions under our ownership, representing approximately $3 billion of GTCR invested capital. -

Not Mitt Romney's Bain Capital: Boston Investment Firm Home To

Not Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital: Boston investment firm home to diverse political views - Business - The Boston Globe Interested in documentaries? Click here to view our latest free screening. TEXT SIZE MANAGE ACCOUNT LOG OUT NEWS BusinessMETRO MARKETS TECHNOLOGY ARTS BUSINESS BETABOSTON SPORTS OPINION Red Sox Live 3 8 POLITICS LIFESTYLE Final MAGAZINE INSIDERS AtTODAY'S Bain, PAPER a broad range of viewpoints is the new reality E-MAIL FACEBOOK TWITTER GOOGLE+ LINKEDIN 57 http://www.bostonglobe.com/...romney-bain-capital-boston-investment-firm-home-diverse-political-views/gAGQyqkSROIoVubvsCXJxM/story.html[5/23/2015 10:37:45 PM] Not Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital: Boston investment firm home to diverse political views - Business - The Boston Globe SUZANNE KREITER/GLOBE STAFF Former Governor Deval Patrick, a Democrat, is joining Bain Capital — an investment firm founded by his predecessor on Beacon Hill, Republican Mitt Romney. By Beth Healy and Matt Rocheleau GLOBE STAFF APRIL 16, 2015 There are two chestnuts that drive Bain Capital partners crazy: First, the notion that they are ruthless capitalists who enjoy firing people. Second, that they are all card-carrying Republicans. Fifteen long years since Mitt Romney left the Boston investment firm he founded, those old impressions still rankle. Enter Deval Patrick, former Massachusetts governor and a Democrat closely aligned with President Obama, named this week a Bain managing director who will focus on “social impact” investing. The newest Bain employee — and the public spirit implied by his new job — would seem to contradict the firm’s old image. But current and former partners, and close observers of the firm say Bain Capital is more of a big tent than many might think. -

Private Equity and Value Creation in Frontier Markets: the Need for an Operational Approach

WhatResearch a CAIA Member Review Should Know Investment Strategies CAIAInvestmentCAIA Member Member Strategies Contribution Contribution Private Equity and Value Creation in Frontier Markets: The Need for an Operational Approach Stephen J. Mezias Afzal Amijee Professor of Entrepreneurship and Family Enterprise Founder and CEO of Vimodi, a novel visual discussion with INSEAD, based at the Abu Dhabi campus application and Entrepreneur in Residence at INSEAD 42 Alternative Investment Analyst Review Private Equity and Value Creation in Frontier Markets Private Equity and Value Creation in Frontier Markets What a CAIA Member Should Know Investment Strategies 1. Introduction ership stakes, earning returns for themselves and the Nowhere else is the operational value creation approach LPs who invested with them. While this clarifies that more in demand than in the Middle East North Africa capturing premiums through ownership transactions is (MENA) region. Advocating and building operational a primary goal for GPs, it does not completely address capabilities requires active investment in business pro- the question of what GPs need to do to make the stakes cesses, human capital, and a long-term horizon. Devel- more valuable before selling the companies in question. oping the capabilities of managers to deliver value from There are many ways that the GPs can manage their in- operations will not only result in building capacity for vestments to increase value, ranging from bringing in great companies, but will also raise the bar for human functional expertise, e.g., sound financial management, talent and organizational capability in the region. In the to bringing in specific sector operational expertise, e.g., long term, direct support and nurturing of the new gen- superior logistics capabilities. -

PE Pulse Quarterly Insights and Intelligence on PE Trends February 2020

PE Pulse Quarterly insights and intelligence on PE trends February 2020 This document is interactive i. ii. iii. iv. v. Contents The PE Pulse has been designed to help you remain current on capital market trends. It captures key insights from subject-matter professionals across EY member firms and distills this intelligence into a succinct and user-friendly publication. The PE Pulse provides perspectives on both recent developments and the longer-term outlook for private equity (PE) fundraising, acquisitions and exits, as well as trends in private credit and infrastructure. Please feel free to reach out to any of the subject matter contacts listed on page 25 of this document if you wish to discuss any of the topics covered. PE to see continued strength in 2020 as firms seek clear air for deployment We expect overall PE activity to remain strong in 2020. From a deal perspective, deployment remains challenging. Geopolitical developments will continue to shape the 2019 was a strong year from a fundraising perspective, Currently, competition for deals is pushing multiples dispersion of activity. In the US, for example, activity has albeit slightly off the high-water mark of 2017. While well above the top of the last cycle. In the US, purchase continued largely unabated, driven by a strong macro valuations and the challenges in deploying capital multiples have reached 11.5x (versus 9.7x in 2007), and backdrop and accommodative lending markets. PE firms continue to raise concerns among some LPs, any 11.1x in Europe (versus 10.3x in 2007). As a result, firms announced deals valued at US$249b, up 3% from last hesitation in committing fresh capital is being offset to are seeking “clearer air” by moving downmarket into the year, making it among the most active years since the a degree by entirely new investors that are moving into growth capital space, where growth rates are higher and global financial crisis (GFC). -

Private Equity and Corporate Governance: Retrospect and Prospect

353 Corporate Governance: An International Review, 2009, 17(3): 353–375 Private Equity and Corporate Governance: Retrospect and Prospect Mike Wright*, Kevin Amess, Charlie Weir and Sourafel Girma ABSTRACT Manuscript Type: Review Research Question/Issue: We assess the corporate governance role and the impact of private equity. Research Findings/Results: Private equity firms are heterogeneous in their characteristics and activities. Nevertheless, a corporate governance structure with private equity involvement provides incentives to reduce agency and free cash flow problems. Additionally, private equity enhances the efficacy of the market for corporate control. Private equity investment is associated with performance gains, with such gains not simply being a result of transfers from other stakeholders. In the short term, the benefits appear clear to outgoing owners and to the new owners and management while in the longer term the benefits are less clear. While non-financial stakeholders argue that other stakeholders suffer in the short and long term, the evidence to support this view is at best mixed. Theoretical Implications: By reviewing a comprehensive selection of theoretical and empirical papers published in refereed academic journals in finance, economics, entrepreneurship, and management as well as publicly available working papers and private equity industry studies, we develop a more complete understanding of private equity investment. Agency theory has shortcomings when applied to the broad sweep of private equity-backed buyout types, as in some cases pre-ownership change agency problems were likely low (e.g., family firms), in some cases the exploitation of growth opportunities owes more to the entrepreneurial behavior of managers than to improved incentives, and in some institu- tional contexts outside Anglo-Saxon countries traditional agency issues are different and stakeholder interests are more important. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

Annual Report 2019 Contents 4 Foreword 93 Report of the Supervisory Board 6 Executive Board 102 Consolidated Financial Statements 103 Consolidated Statement of 8 The Axel Springer share Financial Position 10 Combined Management Report 105 Consolidated Income Statement 106 Consolidated Statement of 13 Fundamentals of the Axel Springer Group Comprehensive Income 24 Economic Report 107 Consolidated Statement of 44 Economic Position of Axel Springer SE Cash Flows 48 Report on risks and opportunities 108 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 60 Forecast Report 109 Consolidated Segment Report 71 Disclosures and explanatory report on the Executive Board pursuant to takeover law 110 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 77 Corporate Governance Report 180 Responsibility Statement 181 Independent Auditor’s Report 187 Boards 2 Group Key Figures in € millions Change yoy 2019 2018 Group Revenues – 2.2 % 3,112.1 3,180.7 Digital revenue share1) 73.3 % 70.6 % 2) EBITDA, adjusted – 14.5 % 630.6 737.9 EBITDA margin, adjusted2) 20.3 % 23.2 % 2) EBIT, adjusted – 21.5 % 414.5 527.9 EBIT margin, adjusted 2) 13.3 % 16.6 % Net income – 35.4 % 134.6 208.4 2) Net income, adjusted – 21.5 % 263.7 335.7 Segments Revenues Classifieds Media 0.1 % 1,213.8 1,212.5 News Media – 4.4 % 1,430.9 1,496.2 Marketing Media 0.8 % 421.5 418.3 Services/Holding – 14.4 % 46.0 53.7 EBITDA, adjusted2) Classifieds Media – 3.8 % 468.4 487.2 News Media – 39.3 % 138.5 228.2 Marketing Media 20.3 % 107.8 89.6 Services/Holding − – 84.1 – 67.0 EBIT, adjusted2) Classifieds Media – 7.1 % 377.9 406.7 News Media – 54.4 % 72.1 158.2 Marketing Media 26.1 % 83.3 66.0 Services/Holding − – 118.6 – 103.0 Liquidity and financial position 2) Free cash flow (FCF) – 38.1 % 214.6 346.9 2) 3) FCF excl. -

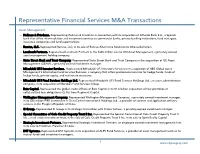

Representative Financial Services M&A Transactions

Representative Financial Services M&A Transactions Asset Management • Hellman & Friedman. Representing Hellman & Friedman in connection with its acquisition of Allfunds Bank S.A., a Spanish bank that offers intermediation and investment services to commercial banks, private banking institutions, fund managers, insurance companies and fund supermarkets. • Ramius, LLC. Represented Ramius, LLC, in its sale of Ramius Alternative Solutions to AllianceBernstein. • Landmark Partners. Represented Landmark Partners in the $465 million sale to OM Asset Management, a privately owned asset management holding company. • State Street Bank and Trust Company. Represented State Street Bank and Trust Company in the acquisition of GE Asset Management (GEAM), a privately owned investment manager. • Mitsubishi UFJ Investor Services. Represented Mitsubishi UFJ Investors Services in its acquisition of UBS Global Asset Management’s Alternative Fund Services Business, a company that offers professional services for hedge funds, funds of hedge funds, private equity, and real estate structures. • Mitsubishi UFJ Fund Services Holdings Ltd. Represented Mitsubishi UFJ Fund Services Holdings Ltd., an asset administration company, in its acquisition of Meridian Fund Services Group. • Bain Capital. Represented the global credit affiliate of Bain Capital in its $1.6 billion acquisition of four portfolios of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) from Regiment Capital. • Wellington Management Company. Represented Wellington Management Company, a privately owned investment manager, in its $85 million PIPE investment in ChinaCache International Holdings Ltd., a provider of content and application delivery services in the People’s Republic of China. • 3i Group. Represented 3i Group in its strategic transaction with Fraser Sullivan, a privately owned investment manager. • Special Committee of Cole Credit Property Trust II Inc. -

How Will Financial Services Private Equity Investments Fare in the Next Recession?

How Will Financial Services Private Equity Investments Fare in the Next Recession? Leading funds are shifting to balance-sheet-light and countercyclical investments. By Tim Cochrane, Justin Miller, Michael Cashman and Mike Smith Tim Cochrane, Justin Miller, Michael Cashman and Mike Smith are partners with Bain & Company’s Financial Services and Private Equity practices. They are based, respectively, in London, New York, Boston and London. Copyright © 2019 Bain & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. How Will Financial Services Private Equity Investments Fare in the Next Recession? At a Glance Financial services deals in private equity have grown on the back of strong returns, including a pooled multiple on invested capital of 2.2x in recent years, higher than all but healthcare and technology deals. With a recession increasingly likely during the next holding period, PE funds need to develop plans to weather any storm and potentially improve their competitive position during and after the downturn. Many leading funds are investing in balance-sheet-light assets enabled by technology and regulatory change. Diligences now should test target companies under stressful economic scenarios and lay out a detailed value-creation plan, including how to mobilize quickly after acquisition. Financial services deals by private equity funds have had a strong run over the past few years, with deal value increasing significantly in Europe and the US(see Figure 1). Returns have been strong as well. Global financial services deals realized a pooled multiple on invested capital of 2.2x from 2009 through 2015, higher than all but healthcare and technology deals (see Figure 2). -

Francesco Pascalizi Appointed Co-Head of the Milan Office Alongside Fabrizio Carretti

PERMIRA STRENGTHENS ITS PRESENCE IN ITALY: FRANCESCO PASCALIZI APPOINTED CO-HEAD OF THE MILAN OFFICE ALONGSIDE FABRIZIO CARRETTI London/Milan, 24 October 2019 –Francesco Pascalizi has been appointed co-head of Permira in Italy and joins Fabrizio Carretti in the leadership of the Milan office. Francesco Pascalizi has worked closely with Fabrizio Carretti for more than 12 years and has contributed significantly to developing Permira’s business in the Italian market, having completed several investments in the industrial and consumer space. He currently serves on the Board of Arcaplanet and Gruppo La Piadineria, acquired by the Permira Funds respectively in 2016 and 2017. Fabrizio Carretti commented: “I am really delighted to have Francesco join the leadership of the Milan team – I am sure that his appointment will further strengthen our position in the Italian market”. Francesco Pascalizi added: “I am very pleased to join Fabrizio and look forward to continue developing Permira’s franchise in Italy, a country to which we are strongly committed”. Francesco Pascalizi joined Permira in 2007 and he is a member of the Industrial Tech & Services team. He has worked on a number of transactions including La Piadineria, Arcaplanet, eDreams OdigeO, and Marazzi Group. Prior to joining Permira, Francesco worked in the private equity group at Bain Capital and before that he was part of M&A team at UBS in both Milan and London. He has a degree in Business Administration from Bocconi University, Italy. ABOUT PERMIRA Permira is a global investment firm. Founded in 1985, the firm advises funds with total committed capital of approximately €44bn (US$48bn) and makes long-term investments, including majority control investments as well as strategic minority investments, in companies with the objective of transforming their performance and driving sustainable growth. -

Annual Report

Building Long-term Wealth by Investing in Private Companies Annual Report and Accounts 12 Months to 31 January 2021 Our Purpose HarbourVest Global Private Equity (“HVPE” or the “Company”) exists to provide easy access to a diversified global portfolio of high-quality private companies by investing in HarbourVest-managed funds, through which we help support innovation and growth in a responsible manner, creating value for all our stakeholders. Investment Objective The Company’s investment objective is to generate superior shareholder returns through long-term capital appreciation by investing primarily in a diversified portfolio of private markets investments. Our Purpose in Detail Focus and Approach Investment Manager Investment into private companies requires Our Investment Manager, HarbourVest Partners,1 experience, skill, and expertise. Our focus is on is an experienced and trusted global private building a comprehensive global portfolio of the markets asset manager. HVPE, through its highest-quality investments, in a proactive yet investments in HarbourVest funds, helps to measured way, with the strength of our balance support innovation and growth in the global sheet underpinning everything we do. economy whilst seeking to promote improvement in environmental, social, Our multi-layered investment approach creates and governance (“ESG”) standards. diversification, helping to spread risk, and is fundamental to our aim of creating a portfolio that no individual investor can replicate. The Result Company Overview We connect the everyday investor with a broad HarbourVest Global Private Equity is a Guernsey base of private markets experts. The result is incorporated, London listed, FTSE 250 Investment a distinct single access point to HarbourVest Company with assets of $2.9 billion and a market Partners, and a prudently managed global private capitalisation of £1.5 billion as at 31 January 2021 companies portfolio designed to navigate (tickers: HVPE (£)/HVPD ($)). -

Golden Goose Announces Majority Investment from Permira Funds

Golden Goose announces majority investment from Permira Funds MILAN - February 12, 2020 – Golden Goose, Permira and The Carlyle Group (NASDAQ: CG) today announced that a company backed by Permira funds has agreed to acquire Carlyle’s majority stake in Golden Goose. Established in 2000 in Venice, Italy, Golden Goose is one of the fastest growing and most distinctive luxury fashion brands, widely recognised for its iconic sneakers. The company has operations in Europe, US and Asia, has a network of 100 Directly Owned Stores (DOS) and a fast growing online presence. Carlyle acquired Golden Goose in March 2017 through Carlyle Europe Partners IV (CEP IV), a European-focused, upper-mid market buyout fund, and Carlyle Asia Growth Partners V (CAGP V). During their ownership, revenues have grown from €100m to estimated revenues in excess of €260m for 2019. Carlyle has a well-established track record in consumer brands globally, with investments including Moncler, Twinset and Hunkmöller. Permira has a strong track record of partnering with global consumer brands and their management teams to successfully grow their businesses and enhance their market leading positions. The consumer team have made 33 investments totaling over €9.6bn with total current sales of €3.6bn. Existing and previous investments include Dr. Martens, the iconic British footwear brand, Reformation, the leading digitally-led clothing brand, Hugo Boss and Valentino. Silvio Campara, CEO at GG said: “Since the foundation of Golden Goose in 2000, we have strived to create innovative products for our customers, combining craftsmanship and a refined and modern style. We thank Carlyle for their support and partnership in leading the company through a phenomenal period of growth. -

THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS a Plan for Regulatory Reform May 2009

COMMITTEE ON CAPITAL MARKETS REGULATION THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS A Plan for Regulatory Reform May 2009 Copyright © 2009. All rights reserved. COMMITTEE ON CAPITAL MARKETS REGULATION The Committee on Capital Markets Regulation is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) research organization dedicated to improving the regulation of U.S. capital markets. Twenty-five leaders from the investor community, business, finance, law, accounting, and academia comprise the Committee’s Membership. The Committee Co-Chairs are R. Glenn Hubbard, Dean of Columbia Business School and John L. Thornton, Chairman of the Brookings Institution. The Committee’s President and Director is Hal S. Scott, Nomura Professor and Director of the Program on International Financial Systems at Harvard Law School. The Committee’s research on the regulation of U.S. capital markets provides policymakers with a nonpartisan, empirical foundation for public policy. COMMITTEE ON CAPITAL MARKETS REGULATION MEMBERS William J. Brodsky Chairman & CEO, Chicago Board Options Exchange; Chairman, World Federation of Exchanges Roel C. Campos* Partner in Charge, Cooley Godward Kronish LLP; Former SEC Commissioner Peter C. Clapman President & CEO, Governance for Owners USA Inc. Samuel A. DiPiazza, Jr. Global CEO, PricewaterhouseCoopers Daniel L. Doctoroff President, Bloomberg L.P. Scott C. Evans** Executive Vice President of Asset Management, TIAA-CREF William C. Freda Vice Chairman & U.S. Managing Partner, Deloitte Robert R. Glauber Visiting Professor, Harvard Law School; Former Chairman & CEO, NASD Robert Greifeld** CEO, The NASDAQ OMX Group, Inc. Kenneth C. Griffin President & CEO, Citadel Investment Group LLC R. Glenn Hubbard Dean and Russell L. Carson Professor of Finance and Economics, Columbia Business School Abigail P.