Interview #20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of 5 Qafela of Ahle Bayt Journey from Karbala to Kufa to Shaam and Then

SIJILL A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER OF FATEMIDAWAT.COM Issue 94 Qafela of Ahle Bayt journey from Karbala to Kufa to Shaam and then Featured updates: Medina after Aashura SIJILL ARTICLE: Ten Virtues of a بسم الل ه الرحمن الرحيم Mumin – (5) Sincere Repentence Having been blessed with the greatest virtue, the valaayat of Amirul يَا َأ يُه َا ال َذِي َن آمَن ُوا ت ُوب ُوا ِإل َى الل َهِ ت َوْب َةً ن َ ُصوحًا Mumineen SA, it is incumbent on us to (Surat al-Tahrim: 8) be worthy of such a great blessing that MARSIYA: Ay Karbala tu hi suna O ye who believe! Turn to Allah with sincere ensures our salvation. Rasulullah SA has said that “he who is given the gift repentance. (rizq, rozi) of thevalaayat of Ali has attained the goodness of this world بسم الل ه الرحمن الرحيم and the Hereafter, and I do not doubt that he will enter jannat. In Ali’s love مَ ْن رَزَق َه ُ الل ه ُ وَلاي َةَ ع َل ِي اب ِن ابيطالب صع ف َقَ ْد َأ َصا َب and valaayat are twenty virtues: 10 in خَيْرَ الدُنْيَا والآخِرةِ، ولا أشُكُ لهُ بِالجَنةِ، وإنَ في حُبِ this world (dunya) and 10 in the ع َلي وَوَلايَتِهِ عِشْرِينَ خَصْ لَة، عَشَرةً مِنها في الدُنيا وعَشَرةً Hereafter (aakherat).” The first of the virtues in this world is zuhd (renouncing في الآخرة* )1( الزهد )2( والحرص على العلم )3( materialism – lit. asceticism – see Sijill والورع في الدين )4( والرغبة في العبادة )5( وتوبة Article 90). The second of the virtues in نصوح this world is desire (lit. -

Beyond the Shatt Al-Arab: How the Fall of Saddam Hussein Changed Iran-Iraq Relations

Beyond the Shatt al-Arab: How the Fall of Saddam Hussein Changed Iran-Iraq Relations Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Rousu, David A. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 18:35:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193287 1 BEYOND THE SHATT AL-ARAB: HOW THE FALL OF SADDAM HUSSEIN CHANGED IRAN-IRAQ RELATIONS by David A. Rousu ________________________ Copyright © David A. Rousu 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: David A. Rousu APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ________________________________ 5/7/2010 Charles D. Smith Date Professor of History 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………. -

The Extent and Geographic Distribution of Chronic Poverty in Iraq's Center

The extent and geographic distribution of chronic poverty in Iraq’s Center/South Region By : Tarek El-Guindi Hazem Al Mahdy John McHarris United Nations World Food Programme May 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Background:.........................................................................................................................................3 What was being evaluated? .............................................................................................................3 Who were the key informants?........................................................................................................3 How were the interviews conducted?..............................................................................................3 Main Findings......................................................................................................................................4 The extent of chronic poverty..........................................................................................................4 The regional and geographic distribution of chronic poverty .........................................................5 How might baseline chronic poverty data support current Assessment and planning activities?...8 Baseline chronic poverty data and targeting assistance during the post-war period .......................9 Strengths and weaknesses of the analysis, and possible next steps:..............................................11 -

Living in Mosul During the Time of ISIS and the Military Liberation: Results from a 40-Cluster Household Survey R

Lafta et al. Conflict and Health (2018) 12:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0167-8 RESEARCH Open Access Living in Mosul during the time of ISIS and the military liberation: results from a 40-cluster household survey R. Lafta1, V. Cetorelli2 and G. Burnham3* Abstract Background: In June 2014, an estimated 1500 fighters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) seized control of Mosul, Iraq’s second city. Although many residents fled, others stayed behind, enduring the restrictive civil and social policies of ISIS. In December 2016, the military activity, known as the liberation campaign, began in east Mosul, concluding in west Mosul in June 2017. Methods: To assess life in Mosul under ISIS, and the consequences of the military campaign to retake Mosul we conducted a 40 cluster-30 household survey in Mosul, starting in March 2017. All households included were present in Mosul throughout the entire time of ISIS control and military action. Results: In June 2014, 915 of 1139 school-age children (80.3%) had been in school, but only 28 (2.2%) attended at least some school after ISIS seized control. This represented a decision of families. Injuries to women resulting from intimate partner violence were reported in 415 (34.5%) households. In the surveyed households, 819 marriages had occurred; 688 (84.0%) among women. Of these women, 89 (12.9%) were aged 15 years and less, and 253 (49.7%) were aged under 18 at the time of marriage. With Mosul economically damaged by ISIS control and physically during the Iraqi military action, there was little employment at the time of the survey, and few persons were bringing cash into households. -

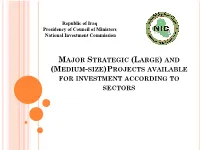

Major Strategic Projects Available for Investment According to Sectors

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission MAJOR STRATEGIC (LARGE) AND (MEDIUM-SIZE)PROJECTS AVAILABLE FOR INVESTMENT ACCORDING TO SECTORS NUMBER OF INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES ACCORDING TO SECTORS No. Sector Number of oppurtinites Major strategic projects 1. Chemicals, Petrochemicals, Fertilizers and 18 Refinery sector 2 Transportation Sector including (airports/ 16 railways/highways/metro/ports) 3 Special Economic Zones 4 4 Housing Sector 3 Medium-size projects 5 Engineering and Construction Industries Sector 6 6 Commercial Sector 12 7 tourism and recreational Sector 2 8 Health and Education Sector 10 9 Agricultural Sector 86 Total number of opportunities 157 Major strategic projects 1. CHEMICALS, PETROCHEMICALS, FERTILIZERS AND REFINERY SECTOR: A. Rehabilitation of existing fertilizer plant in Baiji and the implementation of new production lines (for export). • Production of 500 ton of Urea fertilizer • Expected capital: 0.5 billion USD • Return on Investment rate: %17 • The plant is operated by LPG supplied by the North Co. in Kirkuk Province. 9 MW Generators are available to provide electricity for operation. • The ministry stopped operating the plant on 1/1/2014 due to difficult circumstances in Saladin Province. • The plant has1165 workers • About %60 of the plant is damaged. Reconstruction and development of fertilizer plant in Abu Al Khaseeb (for export). • Plant history • The plant consist of two production lines, the old production line produced Urea granules 200 t/d in addition to Sulfuric Acid and Ammonium Phosphate. This plant was completely destroyed during the war in the eighties. The second plant was established in 1973 and completed in 1976, designed to produce Urea fertilizer 420 thousand metric ton/y. -

TRAGEDY of KARBALA - an ANALYTICAL STUDY of URDU HISTORICAL WRITINGS DURING 19Th > 20Th CENTURY

^^. % TRAGEDY OF KARBALA - AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF URDU HISTORICAL WRITINGS DURING 19th > 20th CENTURY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF JBottor of $t)tlo£;opI)p IN ISLAMIC STUDIES By FAYAZ AHMAD BHAT Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR MUHAMMAD YASIN MAZHAR SIDDIQUI DIRECTOR, SHAH WALIULLAH DEHLAVI RESEARCH CELL Institute of Islamic Studies, A.M.U., Aligarh. DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2003 :^^^^ Fed ir. Comptrf^r Aaad m >«'• Att. M "s/.-Oj Uni^ 0 2 t'S 2C06 THESIS 1 ABSTRACT The sad demise of Prophet Muhammad (SAW) (571- 622AD) created a vacuum in the Muslim Ummah. However, this vacuum was filled by the able guided and pious Khulafa {Khulafa-i-Rashidin) who ruled Ummah one after another. Except the first Khalifah, all the subsequent three Khulafa were unfortunately martyred either by their co-religionists or by antagonists. Though the assassination of Hazrat Umar (RA) did not create any sort of havoc in the Ummah, but the assassination of Hazrat Uthman (RA) caused a severe damage to the unity of Muslim Ummah. This was further aggravated by the internal dissentions caused by the assassination of the third Khalifah during the period of the fourth Khalifah, leading to some bloodshed of the Muslims in two bloody wars of Camel and Si/fin; Hazrat All's assassination was actually a result of that internal strife of the Muslims, dividing the Muslim community into two warring camps. Hazrat Hasan's abdication of the Khilafah tried to bridge the gulf but temporarily, and the situation became explosive once again when Hazrat Muawiyah (RA) nominated his son Yazid as his successor whose candidature was questioned and opposed by a group of people especially by Hazrat Husain (RA) on the ground that he was not fit for the Khilafah. -

Zainab (S.A), from Kufa to Damascus

Zainab (s.a), from Kufa to Damascus About this slide show Zainab (s.a) and other captives are on the way from Kufa to Damascus Paraded in the streets of Damascus Confrontation with Yazid Put in a prison Relocated to good quarters The return to Karbala From Karbala to Medina Zainab (s.a) in Damascus Zainab (s.a) Confronts Yazid Companions Killed Family Members Killed Imam al-Husain Killed Manage the ordeal of the family Confront Ibn Ziyad and Yazid The Captives: Zainab (s.a) in charge The captives consisted of 55 persons: Zainab (s.a) in charge Zainul Abideen (a.s) the only man There were fourteen women And many children, among them was Al-Baaqir (a.s) They were downhearted, had gone through horrendous experience, and Their captors treating them in a demeaning manner: 1. As the vanquished group (versus the victorious Yazid fighters) 2. Who had lost a power struggle in Karbala The nightmare of Karbala haunted the captives day and night They suffered from instability, lack of rest, and anxiety, all that in a strange unfamiliar surroundings They were to go to Damascus, no less than 750 miles away. Fourteen Women as Captors Names of the Women 1. Zainab (s.a) daughter of Ali 8. Sukayna daughter of Al-Hasan 2. Umm Kulthoom daughter of Ali 9. Rabab 3. Fatima daughter of Ali 10. Aati’ka 4. Safiyya daughter of Ali 11. Umm Muhsin Ibn Al-Hasan 5. Ruqayya daughter of Ali 12. Daughter of Muslim Ibn Aqeel 6. Umm Hani daughter of Ali 13. Fidh’dha the Nubian 7. -

Iraq Situation Sources: UNHCR Field Office UNHCR, Global Insight Digital Mapping Elevation © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd

FF II CC SS SS Capital Armistice Demarcation Line Field Information and Administrative boundary Coordination Support Section UNHCR Representation Main road Division of Operational Services UNHCR Sub office Railway Iraq Situation Sources: UNHCR Field office UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping Elevation © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. UNHCR Presence (Above mean sea level) MoDM, IOM, IDP Working Group C Refugee settlement As of April 2008 3,250 to 4,000 metres Refugee camp 2,500 to 3,250 metres The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this Town or village of interest 1,750 to 2,500 metres map do not imply official endorsement 1,000 to 1,750 metres Exclusively for internal UNHCR use !! Main town or village or acceptance by the United Nations. 750 to 1,000 metres ((( Secondary town or village Iraq_SituationMapEthnoGroups_A3LC.WOR ((( ((( ((( 500 to 750 metres ((( Andirin !! ((( ((( ((( ((( Hakkâri ((( Yüksekova Kahramanmaras((( ((( ((( Gercus !! ((( ((( !! ((( ((( Kuyulu ((( Savur International boundary ((( Pazarcik((( Golcuk ((( !! 250 to 500 metres ((( !! ((( ((( !! ((( ((( !! ((( ((( !! ((( Bandar-e Anzali !! ((( !! ((( Karakeci OrumiyehOrumiyeh ((( Kozan ((( ((( OrumiyehOrumiyeh ((( Meyaneh ((( ((( ((( ((( !! ((( !! Turkoglu((( Yaylak((( ((( ((( !! Maraghen ((( Boundary of former Kadirli((( !! ((( Akziyaret ((( Derik ((( ((( ((( 0 to 250 metres ((( ((( (((Cizre ((( Bonab !! ((( ((( !! !! ((( ((( ( ((( Mardin Sume`eh Sara !! ((( Kuchesfahan ( ((( ((( ((( ((( SilopiSilopi !! Palestine Mandate Karaisali((( -

Needs of Internally Displaced Women and Children in Baghdad, Karbala, and Kirkuk, Iraq – PLOS Currents Disasters 6/11/16, 5:59 PM

Needs of Internally Displaced Women and Children in Baghdad, Karbala, and Kirkuk, Iraq – PLOS Currents Disasters 6/11/16, 5:59 PM Needs of Internally Displaced Women and Children in Baghdad, Karbala, and Kirkuk, Iraq June 10, 2016 · Brief Report Citation Lafta R, Aflouk NA, Dihaa S, Lyles E, Burnham G. Needs of Internally Displaced Women and Tweet Children in Baghdad, Karbala, and Kirkuk, Iraq. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2016 Jun 10 . Edition 1. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.fefc1fc62c02ecaedec2c25910442828. Revisions This article is either a revised version or has previous revisions Edition 1 - June 10, 2016 Authors Riyadh Lafta Al Mustansiriya University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Community Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq. Nesreen A Aflouk Al Mustansiriya University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Community Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq. Saba Dihaa College of Health and Medical Technology, Department of Community Health, Baghdad, Iraq. Emily Lyles College of Health and Medical Technology, Department of Community Health, Baghdad, Iraq; Center for Refugee and Disaster Response, Department of International Health, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA. Gilbert Burnham College of Health and Medical Technology, Department of Community Health, Baghdad, Iraq; Center for Refugee and Disaster Response, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA, Baltimore, MD, USA. Abstract Background: The continuing conflict in Iraq has now created an estimated four million internally displaced persons (IDPs). The bulk of recently displaced persons are in Central Iraq, often in insecure and difficult http://currents.plos.org/disasters/article/needs-of-internally-displaced-women-and-children-in-baghdad-karbala-and-kirkuk-iraq/ Page 1 of 20 Needs of Internally Displaced Women and Children in Baghdad, Karbala, and Kirkuk, Iraq – PLOS Currents Disasters 6/11/16, 5:59 PM situations. -

Sorensen IRAQ

Sorensen Last updated: July 11, 2008 Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād View of truck crossing pontoon bridge over river. 1951 x Iraq 1 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Pedestrian traffic on pontoon bridge over river. 1951 x Iraq 2 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Man walking alongside Tigris River looking south 1951 Iraq 3 x towards city. ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Guide and chauffeur standing alongside Tigris River. 1951 Iraq 4 x ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Boats docked side by side on Tigris River. 1951 x Iraq 5 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Looking east towards building on Tigris River. 1951 x Iraq 6 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Vegetable garden underneath palm trees. 1951 x Iraq 7 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Boy and girl standing under palm tree in vegetable 1951 Iraq 8 x garden. ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād View of Tigris River from balcony of Semiarmis Hotel. 1951 Iraq 9 x ME Iraq Baghdād Kadhimain View up road from traffic circle towards al-Khadimain 1951 Iraq 10 x Mosque. ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Waiting for bus to Kirkūk. 1951 x Iraq 11 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Loading buses bound for Kirkūk. 1951 x Iraq 12 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Aerial view of gate to mosque. 1951 x Iraq 13 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Dome of mosque, as viewed from roof. 1951 x Iraq 14 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād View over city from roof of mosque. 1951 x Iraq 15 ME Iraq Baghdād Baghdād Tomb of a King. -

RAPID ASSESSMENT on RETURNS and DURABLE SOLUTIONS March 2021 Markaz Mosul Sub-District - Mosul District - Ninewa Governorate, Iraq

RAPID ASSESSMENT ON RETURNS AND DURABLE SOLUTIONS March 2021 Markaz Mosul Sub-district - Mosul District - Ninewa Governorate, Iraq Situation Overview The situation in Markaz Mosul has been characterised by waves of insecurity In 2020, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) returning to their and associated displacement since 2003. After the start of the Iraq War, the area of origin (AoO) or being re-displaced increased, coupled with persisting sub-district witnessed increasing insecurity and social divisions, particularly challenges in relation to social cohesion, lack of services, infrastructure between 2006 and 2008, sparking the mass displacement of thousands 4 and - in some cases - security in AoO.1 Increased returns were driven in of people. On 10 June 2014, Markaz Mosul fell under the control of the part by the ongoing closure and consolidation of IDP camps; at the time group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), resulting in a of data collection, 16 formal camps and informal sites have been closed or second wave of displacement of around 500,000 people during the first two 5 reclassified as informal sites since camp closures started in mid-October, weeks of occupation. In July 2017, the Iraqi forces and their allies retook with planning ongoing surrounding the future of the remaining camps across Markaz Mosul from ISIL. Since then, insecurity has gradually reduced and Iraq.2 The International Organization for Migration (IOM) Displacement reconstruction has continued, alongside which populations have started to Tracking Matrix (DTM)’s Returnee Master List recorded that over 3,370 return. At the same time, particularly as the city is an economic and social households returned to non-camp locations across the country between hub of northern Iraq, IDPs displaced from other areas have continued to seek 4 January and February 2021.3 safety in Markaz Mosul. -

Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options

CASE STUDY NO. 8 COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options John Hodgson The Pennsylvania State University KAREN GUTTIERI SERIES EDITOR Naval Postgraduate School COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Complex operations encompass stability, security, transition and recon- struction, and counterinsurgency operations and operations consisting of irregular warfare (United States Public Law No 417, 2008). Stability opera- tions frameworks engage many disciplines to achieve their goals, including establishment of safe and secure environments, the rule of law, social well- being, stable governance, and sustainable economy. A comprehensive approach to complex operations involves many elements—governmental and nongovernmental, public and private—of the international community or a “whole of community” effort, as well as engagement by many different components of government agencies, or a “whole of government” approach. Taking note of these requirements, a number of studies called for incentives to grow the field of capable scholars and practitioners, and the development of resources for educators, students and practitioners. A 2008 United States Institute of Peace study titled “Sharing the Space” specifically noted the need for case studies and lessons. Gabriel Marcella and Stephen Fought argued for a case-based approach to teaching complex operations in the pages of Joint Forces Quarterly, noting “Case studies force students into the problem; they put a face on history and bring life to theory.” We developed