Teacher Written Feedback in Efl Yemeni Context: a Qualitative Case Study of Students' Reactions and Utilisations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Chakcharan Ghor province regional hospital Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Faizabad, Afghanistan Faizabad Provincial Hospital Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Ghor province Hazarajat community health project Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Herat Herat Institute of Health Sciences Herat Regional Military Hospital Herat Regional Hospital Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Kabul asia hospital Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Afghanistan Public Health Institute, Ministry of Public Health Ministry of Public Health, Presidency of medical Jurisprudence Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (A-NACP) Afghan Medical College Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science National Medical Library of Afghanistan Institute of Health Sciences Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Health Services Support Project HMIS Health Management Information system 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul National Tuberculosis Program, Darulaman Salamati Health Messenger al-yusuf research institute Health Protection and Research Organisation (HPRO) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Afghan Society Against Cancer (ASAC) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Rabia Balkhi Hospital Cure International Hospital Mental Health Institute Emergency NGO - Afghanistan Al haj Prof. Mussa Wardak's hospital Afghan-COMET (Centre Of Multi-professional Education And Training) Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Afghanistan Mercy Hospital. -

The Challenges of Pharmacy Education in Yemen

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2014; 78 (8) Article 146. STATEMENT The Challenges of Pharmacy Education in Yemen Yaser Mohammed Al-Worafi, PhD Department of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy, Qassim University, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia Submitted September 15, 2013; accepted January 31, 2014; published October 15, 2014. Pharmacy education in Yemen has faced many challenges since its introduction in the 1980s. Most Yemeni pharmacy schools, especially private ones, are experiencing difficulties in providing the right quality and quantity of clinical educational experiences. Most of these challenges are imbedded in a teaching style and curricula that have failed to respond to the needs of the community and country. The slow shift from traditional drug-dispensing to a patient-centered or focused approach in pharmacy practice requires a fundamental change in the roles and responsibilities of both policymakers and educators. The purpose of this paper is twofold: (1) to discuss the challenges facing the pharmacy education in Yemen; (2) to provided recommendations to overcome challenges. Keywords: pharmacy education, Yemen INTRODUCTION and private colleges is 5 years. The program is taught in The establishment of pharmacy colleges in Yemen is English, with Arabic language used in a few courses such relatively new. There are 4 public and 12 private colleges as Arabic and Islamic subjects.1-10 of pharmacy, but only the public colleges and 3 of the Approximately 500 pharmacy students are admitted private colleges are officially recognized. The first public yearly to the recognized public and private pharmacy pharmacy faculty (college) was established in 1987 in colleges in Yemen.10 According to a report by the Central Sana’a. -

FREE to THINK 2020: Report of the Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project

2020 Free to Think Report of the Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project Acknowledgements Scholars at Risk (SAR) gratefully acknowledges the members of higher education communities worldwide who have inspired us through their courage and dedication. We acknowledge especially the researchers contributing to the Academic Freedom Monitoring Project by reporting and analyzing incidents, tracking down sources and witnesses, and helping to develop advocacy responses. We also acknowledge our publication partners—the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey; theUniversity of Los Andes Human Rights Observatory, in Venezuela; and Aula Abierta, also in Venezuela— for their important contributions to this year’s report. We thank the Office of the Provost and New York University for hosting SAR, as well as the many other member institutions, associations, partners, and individuals that contribute to our work beyond the monitoring project. These include especially the Vivian G. Prins Foundation for core support for services for threatened and refugee scholars, the National Endowment for Democracy, the Open Society Foundations, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Charles Koch Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Winston Foundation, the Charina Endowment Fund, Demoret Stiftung, the Microsoft Corporation, Newman’s Own Foundation, our anonymous donors, the members of SAR’s Board and Ambassadors Council, and the many friends of SAR who help us each day to protect more scholars. This report is the result of research conducted by the monitoring project and our publication partners, and thus may not reflect the views of individual network members, institutions, or participating individuals. SAR invites comments on this report or inquiries about our work at [email protected]. -

National Strategy for the Development of Higher Education in Yemen

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN YEMEN Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................3 PART I: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................8 Objective of the Study...................................................................................................................8 Methodology..................................................................................................................................8 Definition and scope..................................................................................................................10 Economic environment.............................................................................................................12 PART 2: THE HIGHER EDUCATION LANDSCAPE .........................................14 A: MAIN FEATURES AND ISSUES .........................................................................................14 B: SWOT ANALYSIS ..................................................................................................................46 C: SUMMARY OF MAIN ISSUES .............................................................................................51 PART 3: VISION AND MISSION.......................................................................58 PART 4: ANALYSIS, OBJECTIVES AND ACTIONS .......................................62 KEY STRATEGIC -

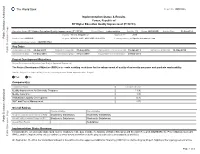

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR15836 Implementation Status & Results Yemen, Republic of RY Higher Education Quality Improvement (P110733) Operation Name: RY Higher Education Quality Improvement (P110733) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 04-Nov-2014 Country: Yemen, Republic of Approval FY: 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): MOHESR PMU Key Dates Board Approval Date 29-Apr-2010 Original Closing Date 31-Aug-2016 Planned Mid Term Review Date 15-Apr-2013 Last Archived ISR Date 10-May-2014 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 01-Sep-2010 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2017 Actual Mid Term Review Date 23-Mar-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The Project Development Objective (PDO) is to create enabling conditions for the enhancement of quality of university programs and graduate employability. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Quality Improvement for University Programs 11.30 Quality Assurance 1.30 Institutional Capacity Development 0.70 M&E and Project Management 2.70 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Substantial Implementation Status Overview Considering the exceptionally challenging country conditions in the past months, the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MOHESR), the Project Management Unit (PMU), and the implementing entities continue to show strong commitment to the project's objectives and associated activities. -

Visualización Y Análisis De La Influencia De Las Universidades

Web Structure and Influence of the Arab Universities of the MENA Zone (Middle East and North Africa): Visualization and Analysis Benjamín Vargas-Quesada* University Professor, Information and Communication Department, University of Granada, Campus Cartuja, Colegio Máximo, 18071 Granada, Spain. (CSIC), Associate unit SCImago Group, Madrid, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: + 34 958 240923; Fax: + 34 958 243490 Cristina Faba-Pérez University Professor, Information and Communication Department, University of Extremadura, Plaza Ibn Marwan, La Alcazaba, 06071, Badajoz, Spain. Khaldoon Mohammad Oglah AL_Dwairi University Professor. Al-Balqa Applied University Al-Salt 19117, Jordan. Félix Moya-Anegón Research Professor, Institute of Policies and Public Property, Superior Council for Scientific Investigation, C/Albasanz, 26-28, 28037, Madrid. Spain. (CSIC), Associate unit SCImago Group, Madrid, Spain. 1.- Introduction The geopolitical zone known as MENA (Middle East and North Africa), occupying so many newspaper front pages last year owing to the “Arab spring” in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Syria, is at the same time largely ignored by the realm of webometrics, scientometrics, and information visualization. The MENA zone would include all 22 countries whose official language is Arabic, and which also belong to the League of Arab States (http://www.arableagueonline.org): Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Bahrain, Comoro Islands, Djibouti, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Syria, -

“Toward Intelligent Solutions for Sustainable De-Velopment “

“Toward Intelligent Solutions for Sustainable De-velopment “ The International Congress of Advanced Technology and Engineering (ICOTEN 2021) July 4-5, 2021 (Virtual Conference) “Toward Intelligent Solutions for Societies' Development. Toward Smart and Sustainable Engineering and Environ- ment. Enhancing Management and Education Polices and Tech- nologies in Crises Time.” Editors: Faisal Saeed Fathey Mohammed Fuad A. Ghaleb Organizing Committee Congress Parton Prof. Dr. Khalid Alwesabi, Minister of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Technical Education, Yemen Congress Honorary Chair Mohammed Saeed Khanbsh, President, Hadhramout University, Yemen Congress General Chair Faisal Saeed,Yemeni Scientists Research Group (YSRG) Conferences Chairs Faisal Saeed, Chair of the International Conference of Intelligent Computing and Informatics (ICOICS 2021) Zaid Shamsan, Chair of the International Conference of Advances in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ICOEEE 2021) Wahdi Ali, Chair of the International Conference of Advances in Bioscience and Biomedical Environment Engi- neering (ICOBBE 2021) Adeeb Qaid, Chair of the International Conference of Advances in Sustainable Environmental Engineering (ICOSEE 2021) Muneer Aziz, Chair of the International Conference of Advances in Applied Sciences (ICOAPS 2021) Nabil Hussein Alfahim, Chair of the International Conference of Advances in Management and Education Tech- nology (ICOMET) IEEE-Yemen Subsection Technical Sponsors Ammar Zahari, Chair of IEEE-Yemen Subsection Mazen Bahashwan, Vice-Chair -

Personal Data Education Work Experience Skills Research Interests

Personal data Name Hasan Mohammed Maridi Citizenship Yemen Birth date 24 Mar 1980 Current address Heavy ion Laboratory, University of Warsaw, ul. Pasteura 5a, 02-093, Warsaw, Poland Permanent address Physics Department, Faculty of Applied Science, Taiz University, Taiz, Yemen Tel. +48 22 55 46204 Mobile +48 536 890 547 ; +962780905984 Email [email protected]; [email protected] Websites https://sites.google.com/site/hasanmaridi; http://www. researchgate.net/profile/Hasan_Maridi2 Education 2010–2014 Doctorate (Ph.D.), Theoretical Physics, Cairo University, Egypt Thesis title: "Calculations of the cross sections for stable and exotic light nuclei". Advisor: Prof. Dr. M. Y. H. Farag. Examiners: Prof. Dr. V. K. Lukyanov, JINR, Dubna, Russia, and Prof. Dr. Angela Bonaccorso, INFN, Pisa, Italy. Best Phd thesis award in Faculty of Science. 2006–2009 Master (M.Sc.), Theoretical Physics, Cairo University, Egypt Thesis title: “Scattering of halo nuclei". Advisor: Prof. M. Y. M. Hassan. Examiner: Prof. Dr. Angela Bonaccorso, INFN, Pisa, Italy. Best master thesis award in Faculty of Science. Grade of Preliminary courses (2006–2007): Distinction with First Class Honors. 2000–2004 Bachelor's degree (B.Sc.), Physics, Cairo University, Egypt Distinction with First Class Honors. Work Experience 2020– Now Researcher, Heavy ion Laboratory, University of Warsaw, 02-093, Warsaw, Poland 2018– 2020 Assistant Professor, Department of Alternative Energy Technology, Faculty of Engineering, Philadelphia University, Amman, Jordan (IIE-SRF fellowship). 2015– Now Assistant Professor of Theoretical Nuclear Physics, Department of Physics, Faculty of Applied Science, Taiz University, Yemen. 2015– 2017 Assistant Professor of Physics, Faculty of Engineering, Hodeidah University, Yemen. 2011– 2014 Graduate research assistant, PhD study, Physics Department, Cairo University, Egypt 2010– 2011 Lecturer, Faculty of Applied Science, Taiz University, Taiz, Yemen. -

Research4life Academic Institutions

Research4Life Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University HERAT HERAT UNIVERSITY Herat Institute of Health Sciences Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Afghan Medical College Kabul 30-Nov-2018 10:49 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 184 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Agricultural University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Kabul Education University Kabul Medical University, Public Health Faculty Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Khatam al Nabieen University Kabul Medical University Kandahar Kandahar University Malalay Institute of Higher Education Kapisa Alberoni University khost,city Shaikh Zayed University, Khost 30-Nov-2018 10:49 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 184 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Lashkar Gah Helmand University Logar province Logar University Maidan Shar Community Midwifery School Makassar Hasanuddin University Mazar-e-Sharif Aria Institute of Higher Education, Faculty of Medicine Balkh Medical Faculty Pol-e-Khumri Baghlan University Samangan Samanagan University Sheberghan Jawzjan university Albania Elbasan University "Aleksander Xhuvani" (Elbasan), Faculty of Technical Medical Sciences Korca Fan S. Noli University, School of Nursing Tirana University of Tirana Agricultural University of Tirana 30-Nov-2018 10:49 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 3 of 184 Country City Institution Name Albania Tirana University of Tirana. -

Differential Predictive Validity of High School Gpa and College Entrance Test Scores for University Students in Yemen

DIFFERENTIAL PREDICTIVE VALIDITY OF HIGH SCHOOL GPA AND COLLEGE ENTRANCE TEST SCORES FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS IN YEMEN by Abdulghani Ali Dawod Al-Hattami B.A., Hodeidah University, 1998 M.Ed., Hodeidah University, 2000 M.A., Loyola University Chicago, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF EDUCATION This dissertation was presented by Abdulghani Ali Dawod Al-Hattami It was defended on February 24, 2012 and approved by Suzanne Lane, Ph.D., School of Education Louis A. Pingel, Ph.D., School of Education Lauren Terhorst, Ph.D., School of Nursing Dissertation Advisor: Clement A. Stone, Ph.D., School of Education ii Copyright © by Abdulghani Ali Dawod Al-Hattami 2012 iii DIFFERENTIAL PREDICTIVE VALIDITY OF HIGH SCHOOL GPA AND COLLEGE ENTRANCE TEST SCORES FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS IN YEMEN Abdulghani Ali Dawod Al-Hattami, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 High school grade point average and college entrance test scores are two admission criteria that are currently used by most colleges in Yemen to select their prospective students. Given their widespread use, it is important to investigate their predictive validity to ensure the accuracy of the admission decisions in these institutions. This study was conducted to investigate the predictive validity of both high school GPA and college entrance test scores used as predictors in the admission process to Yemeni colleges. In addition, the differential predictive validity of high school GPA and college entrance test scores was examined across gender and high school location. -

Default Normal Template

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : Dr. Abdul-Hafeed Ali Fakih Title : Associate Professor of Linguistics Place of Work : Department of English & Department of Translation, Najran . University, KSA Nationality : Yemeni Marital Status : Married Phone : 009966 550 186 509 (Cell phone) e-mail : [email protected] EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Ph.D. in Linguistics (2003), University of Delhi. M. Phil. (Master of Philosophy in Linguistics, 2000). University of Delhi. M.A. (Master of Arts in Linguistics, 1998), University of Delhi. B. A. in English (1991), University of Sana'a, Yemen. PRESENT POSITION 1. Associate Professor of Linguistics at the Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Najran University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2. Associate Professor of Linguistics at the Department of Translation, College of Languages and Translation, Najran University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. PRESENT ACADEMIC EXPERIENCES AND MEMBERSHIPS 1. Academic adviser of the English Department, Faculty of Arts, Najran University, KSA. 2. Member of the English Department Council, Faculty of Arts, Najran University, KSA. 3. Member of the Higher Committee of Academic Development and Quality Assurance, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, University Najran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 4. Member of the Arab Professional Translators Society. 5. Member of the Quality Program & Curriculum Committee, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, University Najran. 6. Member of the Arab Society of English Language Studies: http://asels.org/ PREVIOUS ACADEMIC EXPERIENCES AND MEMBERSHIPS 1. Member of Education and Humanity Center at Najran University representing the Faculty of Arts & Science (2012 - 2014). 2. Member of Ibb University Council representing the Deanship of Center of Languages & Translation (from 20 September, 2008 until 2010). -

Peace Research in the Arab World an Inventory 2011 by Adéle Aranki

Peace Research in the Arab World The aim of this study is to locate the universities in the Arab UPPSALA countries which teach or house a research milieu dealing with peace UNIVERSITET An Inventory 2011 and conflict research. By The aim is also to identify the level of teaching and presents information on course descriptions Adéle Aranki Nassar There are more than 450 universities with different approaches, for instance, in political science and multidisciplinary programs such as diplomacy, international relations, strategic studies, law and related fields in humanities in total 73 universities and institutions are specifically identified. Report No.97 Department of Peace and Conflict Research Uppsala University Preface by Peter Wallensteen Peace Research in the Arab world An Inventory 2011 By Adéle Aranki Nassar Preface by Peter Wallensteen Department of Peace and Conflict Research Abstract This study locates the universities in the Arab countries that teach or house a research milieu dealing with peace and conflict research. It also identifies the level of teaching and presents information on course descriptions. There are more than 450 universities with different approaches, for instance, in political science and multidisciplinary programs such as diplomacy, international relations, strategic studies, law and related fields in humanities. In total, 73 universities and institutions are specifically identified in this report. Nassar, Adele Aranki. 2012. Peace Research in the Arab World. An Inventory 2011, Uppsala. Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Report 97, 65 pp. ISBN 978-91-506-2291-1 Keyword: Universities, Arab Countries, League of Arab States, Peace Research Adele Aranki Nassar, Uppsala University, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Box 514, SE-75120 Uppsala, Sweden.