An Analysis of Past and Present Experiences of Female On- Camera Sportscasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fox Sports Live Event and Studio Programming Schedule All

FOX SPORTS LIVE EVENT AND STUDIO PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE ALL TIMES EASTERN UPDATED AS OF 6/22/2020 *Includes full FS1 schedule, as well as live events and premieres on FOX and FS2 - SUBJECT TO CHANGE MONDAY 6/22/2020 FS1 REPEAT NASCAR NASCAR CUP SERIES RACING - Homestead 6:00AM FS1 PREMIERE STUDIO TMZ SPORTS 8:00AM FS1 LIVE STUDIO FIRST THINGS FIRST 8:30AM FS1 REPEAT STUDIO TMZ SPORTS 9:30AM FS1 REPEAT USGA U.S. OPEN 2002: THE PEOPLE'S OPEN 10:00AM FS1 REPEAT STUDIO FIRST THINGS FIRST 11:00AM FS1 LIVE STUDIO THE HERD 12:00PM FS1 REPEAT PBA PBA BOWLING - PBA STRIKE DERBY 3:00PM FOX LIVE NASCAR NASCAR CUP SERIES RACING - Talladega 3:00PM FS1 REPEAT PBA PBA BOWLING - SUMMER CLASH 5:00PM FS1 PREMIERE SOCCER FOX INDOOR SOCCER 7:00PM FS1 PREMIERE SOCCER GREATEST GAMES: FIFA WORLD CUP - USA vs. Algeria (6/23/2010) 7:30PM FS2 REPEAT NASCAR GREATEST RACES: NASCAR CUP SERIES - Talladega (4/25/2010) 8:00PM FS1 PREMIERE MLB GREATEST GAMES: MLB NLDS GAME 1 - Cincinnati Reds at Philadelphia Phillies (10/6/2010) 9:30PM FS2 REPEAT RED BULL RED BULL X-FIGHTERS - Madrid 11:00PM FS1 PREMIERE STUDIO TMZ SPORTS 12:30AM FS2 REPEAT RED BULL RED BULL X-FIGHTERS - Madrid 12:30AM FS1 PREMIERE NASCAR NASCAR CUP SERIES RACING - Talladega 1:00AM FS1 REPEAT NASCAR UNRIVALED: Earnhardt vs. Gordon 4:00AM FS1 REPEAT STUDIO FOX SPORTS THE HOME GAME: Dick Stockton and Mark Schlereth 5:00AM TUESDAY 6/23/2020 FS1 REPEAT STUDIO THE HERD 6:00AM FS1 LIVE STUDIO FIRST THINGS FIRST 8:30AM FS1 REPEAT STUDIO TMZ SPORTS 9:30AM FS1 REPEAT NASCAR REFUSE TO LOSE: Jeff Gordon and the 1997 Daytona 500 10:00AM FS1 REPEAT STUDIO FIRST THINGS FIRST 11:00AM FS1 LIVE STUDIO THE HERD 12:00PM FS1 REPEAT MLB GREATEST GAMES: MLB WORLD SERIES GAME 6 - Cleveland Indians at Atlanta Braves (10/28/1995) 3:00PM FS1 LIVE STUDIO NASCAR RACE HUB 6:00PM FS1 PREMIERE WWE WWE: 2008 ROYAL RUMBLE 7:00PM FS1 REPEAT WWE WWE: 2008 ROYAL RUMBLE 11:00PM FS1 PREMIERE STUDIO TMZ SPORTS 3:00AM FS1 REPEAT SOCCER GREATEST GAMES: FIFA WORLD CUP - USA vs. -

That Face! Some Seek Modeling, Othershavemodelingthrustuponthem

Mengucci: On Our Short List ON OUR SHORT LIST People of note That Face! Some seek modeling, othershavemodelingthrustuponthem. shops and seminars in California ing for television and film. "The and G.E. employees. PEAKING OF FASHION, and Arizona. Effective walking time is right for me and for my But getting the message out to the SSylviaCole Mackey epito methods, stage and backstage eti look," she says. "I've got my photos right people is only half her job. mizes 1t. quette, ramp formations, and phys ready." As vice president for corporate She's an international runway ical fitness are among the trade tips public relations for all of G.E., model who has worn and displayed Mackey discusses in her seminars. JOYCE HER&EIIU '13 Hergenhan also takes an active role the clothing ofnearly every famous The inost outrageous outfit she's in policy-making decisions at the designer in the world. In outfits ever worn? "This beautiful $8,000 Corporate corporation. costing more than some automo white rhinestone and feather gown At many companies, says biles, she's wooed audiences in with a matching jacket. You could Voice Hergenhan, public relations France, Italy, the Philippines, and roll this thing up in a ball and it officers are kept in the dark during locations all over the United States. wouldn't wrinkle," she says. HEN CORPORATE policy-making sessions. But G.E.'s "I like the runway," says Mackey. Feathers would fall off in different W policy decisions are chairman, she says, is a strong pro "I like the audience contact, the eye places, and the designer would tell made at General Elec ponent of communications. -

Oakland Athletics Virtual Press

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Media Release Oakland Athletics Baseball Company 7000 Coliseum Way Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 Public Relations Facsimile 510-562-1633 www.oaklandathletics.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 31, 2011 Legendary Oakland A’s Announcer Bill King Again Among Leading Nominees for Ford C. Frick Award Online Balloting Begins Tomorrow and Continues Through Sept. 30 OAKLAND, Calif. – No baseball broadcaster was more decisive—or distinctive—in the big moment than the Oakland A’s late, great Bill King. Now, it’s time for his legions of ardent supporters to be just as decisive in voting him into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Starting tomorrow, fans of the legendary A’s announcer can cast their online ballot for a man who is generally regarded as the greatest broadcaster in Bay Area history when the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Facebook site is activated for 2012 Ford C. Frick Award voting during the month of September. King, who passed away at the age of 78 in 2005, was the leading national vote-getter in fan balloting for the Frick Award in both 2005 and 2006. Following his death, the A’s permanently named their Coliseum broadcast facilities the “Bill King Broadcast Booth” after the team’s revered former voice. Online voting for fan selections for the award will begin at 7 a.m. PDT tomorrow, Sept. 1, at the Hall of Fame’s Facebook site, www.facebook.com/baseballhall, and conclude at 2 p.m. PDT Sept. 30. The top three fan selections from votes tallied at the site during September will appear on the final 10-name ballot for the award. -

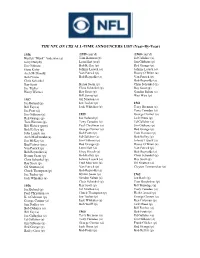

THE NFL on CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year)

THE NFL ON CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year) 1956 (1958 cont’d) (1960 cont’d) Hartley “Hunk” Anderson (a) Tom Harmon (p) Ed Gallaher (a) Jerry Dunphy Leon Hart (rep) Jim Gibbons (p) Jim Gibbons Bob Kelley (p) Red Grange (p) Gene Kirby Johnny Lujack (a) Johnny Lujack (a) Arch McDonald Van Patrick (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Bob Prince Bob Reynolds (a) Van Patrick (p) Chris Schenkel Bob Reynolds (a) Ray Scott Byron Saam (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Joe Tucker Chris Schenkel (p) Ray Scott (p) Harry Wismer Ray Scott (p) Gordon Soltau (a) Bill Symes (p) Wes Wise (p) 1957 Gil Stratton (a) Joe Boland (p) Joe Tucker (p) 1961 Bill Fay (a) Jack Whitaker (p) Terry Brennan (a) Joe Foss (a) Tony Canadeo (a) Jim Gibbons (p) 1959 George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) Joe Boland (p) Jack Drees (p) Tom Harmon (p) Tony Canadeo (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bill Hickey (post) Paul Christman (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Bob Kelley (p) George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) John Lujack (a) Bob Fouts (p) Tom Harmon (p) Arch MacDonald (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bob Kelley (p) Jim McKay (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Bud Palmer (pre) Red Grange (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Van Patrick (p) Leon Hart (a) Van Patrick (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Elroy Hirsch (a) Bob Reynolds (a) Byrum Saam (p) Bob Kelley (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Ray Scott (p) Ray Scott (p) Fred Morrison (a) Gil Stratton (a) Gil Stratton (a) Van Patrick (p) Clayton Tonnemaker (p) Chuck Thompson (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Joe Tucker (p) Byrum Saam (p) 1962 Jack Whitaker (a) Gordon Saltau (a) Joe Bach (p) Chris Schenkel -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Nominees for the 29 Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

NOMINEES FOR THE 29 TH ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCE AT IMG WORLD CONGRESS OF SPORTS Winners to be Honored During the April 28 th Ceremony At Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frank Chirkinian To Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – March 13th, 2008 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards at the IMG World Congress of Sports at the St. Regis Hotel in Monarch Bay/Dana Point, California. Peter Price, CEO/President of NATAS was joined by Ross Greenberg, President of HBO Sports, Ed Goren President of Fox Sports and David Levy President of Turner Sports in making the announcement. At the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards, winners in 30 categories including outstanding live sports special, sports documentary, studio show, play-by-play personality and studio analyst will be honored. The Awards will be given out at the prestigious Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center located in the Time Warner Center on April 28 th , 2008 in New York City. In addition, Frank Chirkinian, referred to by many as the “Father of Televised Golf,” and winner of four Emmy ® Awards, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award that evening. Chirkinian, who spent his entire career at CBS, was given the task of figuring out how to televise the game of golf back in 1958 when the network decided golf was worth a look. Chirkinian went on to produce 38 consecutive Masters Tournament telecasts, making golf a mainstay in sports broadcasting and creating the standard against which golf telecasts are still measured. -

Versatile Fox Sports Broadcaster Kenny Albert Continues to Pair with Biggest Names in Sports

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Erik Arneson, FOX Sports Wednesday, Sept. 21, 2016 [email protected] VERSATILE FOX SPORTS BROADCASTER KENNY ALBERT CONTINUES TO PAIR WITH BIGGEST NAMES IN SPORTS Boothmates like Namath, Ewing, Palmer, Leonard ‘Enhance Broadcasts … Make My Job a Lot More Fun’ Teams with Former Cowboy and Longtime Broadcast Partner Daryl ‘Moose’ Johnston and Sideline Reporter Laura Okmin for FOX NFL in 2016 With an ever-growing roster of nearly 250 teammates (complete list below) that includes iconic names like Joe Namath, Patrick Ewing, Jim Palmer, Jeremy Roenick and “Sugar Ray” Leonard, versatile FOX Sports play-by-play announcer Kenny Albert -- the only announcer currently doing play-by-play for all four major U.S. sports (NFL, MLB, NBA and NHL) -- certainly knows the importance of preparation and chemistry. “The most important aspects of my job are definitely research and preparation,” said Albert, a second-generation broadcaster whose long-running career behind the sports microphone started in high school, and as an undergraduate at New York University in the late 1980s, he called NYU basketball games. “When the NFL season begins, it's similar to what coaches go through. If I'm not sleeping, eating or spending time with my family, I'm preparing for that Sunday's game. “And when I first work with a particular analyst, researching their career is definitely a big part of it,” Albert added. “With (Daryl Johnston) ‘Moose,’ for example, there are various anecdotes from his years with the Dallas Cowboys that pertain to our games. When I work local Knicks telecasts with Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier on MSG, a percentage of our viewers were avid fans of Clyde during the Knicks’ championship runs in 1970 and 1973, so we weave some of those stories into the broadcasts.” As the 2016 NFL season gets underway, Albert once again teams with longtime broadcast partner Johnston, with whom he has paired for 10 seasons, sideline reporter Laura Okmin and producer Barry Landis. -

US Open Mixed Doubles Champion Leaderboard Mixed Doubles Champion Leaders Among Players/Teams from the Open Era Leaderboard: Titles Per Player

US Open Mixed Doubles Champion Leaderboard Mixed Doubles Champion Leaders among players/teams from the Open Era Leaderboard: Titles per player (8) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Margaret Court (AUS) 1969 1970 1972 (1961 1962 1963 1964 1965) (4) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Bob Bryan (USA) 2002 2003 2006 2010 Owen Davidson (USA) 1971 1973 (1966 1967) Billie Jean King (USA) 1971 1973 1976 (1967) Marty Riessen (USA) 1969 1970 1972 1980 (3) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Max Mirnyi (BLR) 1998 2007 2013 Jamie Murray (GBR) 2017 2018 2019 Martina Navratilova (USA) 1985 1987 2006 Todd Woodbridge (AUS) 1990 1993 2001 (2) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Mahesh Bhupathi (IND) 1999 2005 Manon Bollegraf (NED) 1991 1997 Kevin Curren (RSA) 1981 1982 Patrick Galbraith (USA) 1994 1996 Martina Hingis (SUI) 2015 2017 Bethanie Mattek-Sands (USA) 2018 2019 Frew McMillan (RSA) 1977 1978 Leander Paes (IND) 2008 2015 Lisa Raymond (USA) 1996 2002 Elizabeth Sayers Smylie (AUS) 1983 1990 Anne Smith (USA) 1981 1982 Betty Stöve (NED) 1977 1978 Bruno Soares (BRA) 2012 2014 *** (13) MOST US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES OF ALL TIME (Open Era and Before) Margaret Osborne DuPont 1943 1944 1945 1946 1950 1956 1958 1959 1960 Leaderboard: Titles per team (3) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Margaret Court (AUS) and Marty Riessen (USA) 1969 1970 1972 (2) US OPEN MIXED DOUBLES TITLES Bethanie Mattek-Sands (USA) and Jamie Murray (GBR) 2018 2019 Anne Smith (USA) and Kevin Curren (RSA) 1981 1982 Betty Stöve (NED) and Frew McMillan (RSA) 1977 1978 *** (4) MOST “TEAM” US MIXED OPEN DOUBLES TITLES -

View Tree Vaello's Resume

Tree Vaello, Makeup Artist www.pbtalent.com Magazines Self Better Homes and Prevention Glamour Gardens Cigar Aficionado Vogue Real Simple Snowboarder Sports Illustrated Nickelodeon Magazine Dwell Teen People Details HGTV Magazine Teen Maxim Essence Cosmogirl Popular Photography Ebony Seventeen Variety Southern Living Conde Nast Traveler Food & Wine Blender People Vegetarian Times Rolling Stone Southern Brides The New Yorker Vibe Us Weekly Vanity Fair Newsweek In Touch Weekly Men's Health Time Entertainment Weekly Shape Playboy Money Health Texas Monthly Forbes Marie Claire Discover Fortune More Popular Science Harvard Business Review Natural Health Runner's World Bridal Bridal Guide Lifetime Stuff Details Lucky Teen People Dominoe Modern Bride Texas Monthly Essence Newsweek Vibe Fashion Spectrum 002 Vibe Vixen Gloss Onyx Vogue H Texas Papercity Yellow In Style Weddings Self Jones Sports Illustrated Celebs Tilda Swinton Ice Cube Dave Navarro Anna Nicole Smith Carmen Electra Dwayne "The Rock" Alexis Bledel George Foreman Johnson Aerosmith Evander Holyfield Arnold Schwarzenegger Kelly Clarkson Kathy Najimy NFL David Carr Eddie George MLB Brad Ausmus Alice "Lefty" Hohlmayer Octavio Dotel (Hall of Fame) Richard Hidalgo NBA Hakeem Olajuon Scotty Pippen Charles Barkley Magic Johnson Julius Erving (Hall of Fame) Tennis James Blake Andy Roddick WNBA Sheryl Swoops Olympic Gold Medalists Carl Lewis: Track Steven Lopez: Kickboxing Dominique Moceanu: Gymnastics Nancy Lieberman: Basketball Laura Wilkinson: Diving News Anchors & Correspondents Marv Albert Maria Menounos Willow Bay Ahmad Rashad Bob Costas Dominique Sachse Lisa Foranda Hannah Storm Jerome Gray Runway Armani Michael Kors Chanel Diane von Furstenburg Gucci Escada . -

The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF 32 nd ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS Al Michaels Honored with Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – May 2, 2011 – The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) announced the winners tonight of the 32 nd Annual Sports Emmy® Awards at a special ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City. Winners in 33 categories including outstanding live sports special, live series, sports documentary, studio show, promotional announcements, play-by-play personality and studio analyst were honored. The awards were presented by a distinguished group of sports figures and television personalities including Cris Collinsworth (sports analyst for NBC’s “Sunday Night Football”); Dan Hicks ( NBC’s Golf host); Jim Nantz (lead play-by-play announcer of The NFL on CBS and play-by-play broadcaster for NCAA college basketball and golf on CBS); Vern Lundquist (CBS Sports play-by-play broadcaster); Chris Myers (FOX Sports Host); Scott Van Pelt (anchor, ESPN’s Sportscenter and ESPN’s radio show, “The Scott Van Pelt Show”); Hannah Storm (anchor on the weekday morning editions of ESPN’s SportsCenter); Mike Tirico (play-by-play announcer for ESPN's NFL Monday Night Football, and golf on ABC); Bob Papa (HBO Sports Broadcaster); Andrea Kremer (Correspondent, HBO’s “Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel”); Ernie Johnson (host of Inside the NBA on TNT); Cal Ripken, Jr. (TNT Sports Analyst and member of Baseball’s Hall of Fame); Ron Darling (TNT & TBS MLB Analyst and former star, NY Mets); Hazel Mae (MLB Network host, “Quick Pitch”); Steve Mariucci (Former NFL Coach and NFL Network Analyst); Marshall Faulk (Former NFL Running Back and NFL Network Analyst); and Harold Reynolds (MLB Network Studio Analyst). -

Issue 4 BASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERSBASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION the OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the NATIONAL CONTENTS

WE’RE PROUD TO SUPPORT THE NATIONAL BASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERS ASSOCIATION Being Chicago’s Bank™ means doing our part to give back to the local charities and social organizations that unite and strengthen our communities. We’re particularly proud to support the National Basketball Retired Players Association and its dedication to assisting former NBA, ABA, Harlem Globetrotters, and WNBA players in their CHICAGO’S BANK TM transition from the playing court into life after the game, while also wintrust.com positively impacting communities and youth through basketball. Banking products provided by Wintrust Financial Corp. Banks. LEGENDS Issue 4 BASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION BASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERS BASKETBALL RETIRED PLAYERS THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE CONTENTS of the NATIONAL KNUCKLEHEADS PODCAST NATIONAL HOMECOMING: p.34 TWO PEAS JUWAN HOWARD IS p.2 PROUD AND A POD BACK AT MICHIGAN In Partnership with The Players’ Tribune, the Ready to bring NBA swagger to the storied Knuckleheads Podcast Has Become a Hit with program where he once played PARTNER Fans and Insiders Alike. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE KNUCKLEHEADS PODCAST p.2 TWO PEAS AND A POD OF THE KEYON DOOLING NANCY LIEBERMAN p.6 BEYOND THE COURT p.30 POWER FORWARD 2019 LEGENDS CONFERENCE p.11 WOMEN OF INFLUENCE SUMMIT PUTS BY NANCY LIEBERMAN SPOTLIGHT ON OPPORTUNITY p.12 NBRPA HOSTS ‘BRIDGING THE GAP’ NBA AND It’s a great time to be a female in the SUMMIT CONNECTING CURRENT AND game of basketball. FORMER PLAYERS p.13 BUSINESS AFTER BASKETBALL NBRPA. p.14 THE FUTURE IS FRANCHISING “IT’S ABOUT GOOD VIBES, p.15 HAIRSTYLES ON THE HARDWOOD NOT CONCENTRATING ON FAREWELL, ORACLE ARENA ANYTHING NEGATIVE. -

Are Drugs Destroying Sport?

Can C 0 U n t r i e s Fin d Coo per a tiD n Ami d the R u i nos 0 feD n f lie t ? ARE DRUGS IN THI S IS SUE DESTROYING The Gann Years: Colm Connolly '91 Wins Hail to "The Counselor" A Retrospective High-Profile Murder Case Sonja Henning '95 SPORT? Page 8 Letters to the Editor If you want to respond to an article in Duke Law, you can e-mail the editor at [email protected] or write: Mirinda Kossoff Duke Law Magazine Duke University School of Law Box 90389 Durham, NC 27708-0389 , a Interim Dean's Message Features Ethnic Strife: Can Countries Find Cooperation Amid the Ruins of Conflict? .. ..... ... ...... ...... ...... .............. .... ... ... .. ............ 2 The Gann Years: A Retrospective .. ............. ..... ................. .... ..... .. ................ ..... ...... ......... 5 Are Drugs Destroying Sport? .. ..................................... .... .. .............. .. ........ .. ... ....... .... ... 8 Alumni Snapshots Colm Connolly '91 Wins Conviction and Fame in High-Profile Murder Case ................... .................. ... .. ..... ..... ... .... .... ...... ....... ....... ..... 12 Sonja Henning '95: Hail to "The Counselor" on the Basketball Court ........................ .. 14 U.N. Insider Michael Scharf '88 Puts International Experience to Work in Academe ................................... ..................... ... .............................. ....... 15 Faculty Perspectives Q&A: Can You Treat a Financially Troubled Country Like a Bankrupt Company? .. ..... ... 17 The Docket Professor John Weistart: The Man