Part 1. Evolution of the Concept and Dynamic Records for Smile Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's in YOUR Clinical Bag of Tricks? Page 12 Self-Ligating Brackets

The Biggest Risk is the One You Can Manage by Dr. Donald E. Machen, page 43 October 2011 – Volume 4, Issue 8 Message Board What’s in YOUR Clinical Bag of Tricks? page 12 Focus On Self-ligating Brackets page 49 Publications Mail Agreement No. 40902037 A Division of Farran Media, LLC www.orthotown.com Finally. A system that puts control back in your hands. It’s Your Choice: Fully Interactive or Dual Activation System Interactive Anteriors and Passive Posteriors s-ULTIPLEPRESCRIPTIONOPTIONS s(OOKOPTIONAVAILABLEONALL posterior teeth and laterals s4HREEBICUSPIDPADOPTIONS sEmpower SL molars available soon MADE IN THEHE USAUSA www.empowerbraces.com contents October 2011 43 From right: Paul Humphrey, president; Doug Hurford, corporate controller; Sandy McPherson, office manager; and Karri Denny, marketing coordinator. 34 4949 Photograph by John Fedele Articles Advansync, Anyone? 30 Herbst and Advansync each have a following. Have you ever considered switching? The Biggest Risk is One You Can Manage Dr. Donald E. Machen discusses the importance of developing 43 Which Bands (Company)? a strategic plan as well as a regular and frequent protocol With so many to choose from, docs discuss what bands they for review of your personal financial investments with your 33 use and why. investment adviser. Orthodontists Are Finding “There’s an App for That” 46 Angela Weber explores the benefits and current opportunities In This Issue of mobile phone apps for your practice’s Web site. The Truth About Self-ligating Brackets On Orthotown.com 49 Orthotown Magazine surveyed several orthodontic companies, 4 asking all about their self-ligating bracket systems, making it easier than ever to find the system right for you. -

The Concept of a New Dental Disease: Orthodontosis and Orthodontitis

Journal of Dental Health, Oral Disorders & Therapy The Concept of a New Dental Disease: Orthodontosis and Orthodontitis Abstract Research Article Introduction: Angle’s 110 year old classification of malocclusion lacks verifiable Volume 1 Issue 5 - 2014 scientific validity, and lacks substantiation on whether ideal occlusion significantly 1 2 locationimproves of oral bone function in the horizontal or provides dimension. significant benefits in oral or general health. We Anthony D Viazis , Evangelos Viazis and propose a new orthodontic classification based on evaluating the position of roots and Tom C Pagonis3* Materials and Methods: Thousands of completed orthodontic cases, with an 1Orthodontist, Private Practice, USA 2Private Practice, Greece 3Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials overwhelming majority treated non-extraction were subjected to photographic and of Sciences, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, USA radiographic evaluation. Based upon this we propose new orthodontic classifications *Corresponding author: in the horizontal dimension caused by the displaced root(s) of the tooth, typically palatallya. Orthodontosis, or lingually. defined as the non-inflammatory deficiency of the alveolar bone Tom C Pagonis, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Sciences, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, 188 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA, Tel: +1617-432-5846; Fax: +1617-432- b.Discussion: Orthodontitis To date, defined a link as betweenexcess soft malocclusions tissue manifestation and periodontal and chronic condition inflammation. remains 0901;Received: Email: August 24, 2014 | Published: September 30, 2014 and treated accordingly based on their own individual genetic and morphologic appearanceunclear and rather controversial. than an arbitraryWith this ideal. new classification patients will be diagnosed Conclusion: is proposed for malpositioned teeth based on the clinical morphology, appearance A new orthodontic classification namely Orthodontosis and Orthodontitis orthodonticand contour therapeuticof the alveolar modalities. -

ANGELALIGN TECHNOLOGY INC. 時代天使科技有限公司 (The “Company”) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability)

The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission take no responsibility for the contents of this Application Proof, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Application Proof. Application Proof of ANGELALIGN TECHNOLOGY INC. 時代天使科技有限公司 (the “Company”) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) WARNING The publication of this Application Proof is required by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Exchange”) and the Securities and Futures Commission (the “Commission”) solely for the purpose of providing information to the public in Hong Kong. This Application Proof is in draft form. The information contained in it is incomplete and is subject to change which can be material. By viewing this document, you acknowledge, accept and agree with the Company, its sponsor, advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate that: (a) this document is only for the purpose of providing information about the Company to the public in Hong Kong and not for any other purposes. No investment decision should be based on the information contained in this document; (b) the publication of this document or supplemental, revised or replacement pages on the Exchange’s website does not give rise to any obligation of the Company, its sponsor, advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate to proceed with an offering in Hong Kong or any other -

University of Würzburg Medical Faculty Research Report 2010

University of Würzburg University of Würzburg Universitätsklinikum Würzburg Medical Faculty Medical Faculty Josef-Schneider-Str. 2 · 97080 Würzburg 2010 Report – Research University of Würzburg Medical Faculty http://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/ueber/fakultaeten/ Research Report 2010 medizin/startseite/ University of Würzburg Medical Faculty Research Report 2010 Content 1 General Part 1.1 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Medical Education .................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Students’ Representatives ......................................................................................................................................... 13 1.4 The History of the Würzburg Medical Faculty ............................................................................................................... 14 2. Research Institutes 2.1 Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Chair of Anatomy I .............................................................................................. 16 2.2 Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Chair of Anatomy II ............................................................................................. 18 2.3 Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Chair of Anatomy III ........................................................................................... -

Maxillary Molar Distalization with No-Compliance Fixed Orthodontic Equipment

dentistry journal Review Dentoskeletal Class II Malocclusion: Maxillary Molar Distalization with No-Compliance Fixed Orthodontic Equipment Vincenzo Quinzi 1 , Enrico Marchetti 1 , Luigi Guerriero 1, Floriana Bosco 2, Giuseppe Marzo 1 and Stefano Mummolo 1,* 1 Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, Piazzale Salvatore Tommasi 1, L’Aquila 67100 Coppito, Italy; [email protected] (V.Q.); [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (G.M.) 2 Private practice in 20121 Milan, Italy; boscofl[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 January 2020; Accepted: 28 February 2020; Published: 18 March 2020 Abstract: Dentoskeletal class II malocclusion due to a protruded upper dental arch is a major reason for an orthodontic treatment. In these cases, the correction of class II can be hindered by molar distalization, obtained with ‘no-compliance therapy’ that involves the use of appliances which minimize the need for such co-operation and attempt to maximize the predictability of results. The aim of this review was to outline the effectiveness of no-compliance fixed orthodontic devices in the molar distalization. After selection according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 16 articles from 2000 to 2019 were qualified for the final analysis. The literature shows various no-compliance fixed devices whose effect is to distalize the maxillary molars. The present revision allows to conclude that there is a need to increase the number of studies, especially with regard to the most recently introduced devices in the literature. The analysed studies allow to hypothesize that these appliances act with a minimal variability of molar distalization and disto-inclination among them, although different effects among the appliances can be observed as regards to the anchorage. -

Prospectus, You Should Obtain Independent Professional Advice

IMPORTANT IMPORTANT: If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. ANGELALIGN TECHNOLOGY INC. 時代天使科技有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Global Offering Total number of Offer Shares under the : 16,829,600 Shares (subject to the Over- Global Offering allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Public Offer Shares : 1,683,000 Shares (subject to adjustment) Number of International Offer Shares : 15,146,600 Shares (subject to adjustment and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$173.00 per Offer Share, plus brokerage of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and Hong Kong Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application and subject to refund) Nominal value : US$0.0001 per Share Stock code : 6699 Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. A copy of this prospectus, having attached thereto the documents specified in “Documents Delivered to the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong and Available for Inspection” in Appendix V to this prospectus, has been registered by the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by section 342C of the Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance (Chapter 32 of the Laws of Hong Kong). -

Souvenir Copy

Souvenir Copy November2015 BOSNEWSSUPPLEMENT 1 8th International Orthodontic Congress 8th International Orthodontic Congress November2015 BOSNEWSSUPPLEMENT 2 8th International Orthodontic Congress ExCeL London 27 – 30 September 2015 Huge thanks are due to: Dina Slater To the Executive of the And last, but not least, James Spencer Orthodontic Technicians a massive thanks to the My Organising Committee: Ann Wright Association 6,000 delegates, without whom there would not Alex Cash To the BOS Board of To the Session Chairs have been a Congress. Stephen Chadwick Trustees Guy Deeming To the Poster Presenters I hope you enjoy this Andrew DiBiase To the WFO Executive souvenir supplement. Nigel Fox Committee To the Educational Grant Trevor Hodge Recipients Jonathan Sandler Ama Johal To the Speakers Chairman, 8th IOC Ben Lewis To the Exhibitors and Simon Littlewood To the World Village Day Sponsors Rye Mattick organisers Tania Murphy To the Stewards Alison Murray To the Executive of the Kevin O’Brien Orthodontic National To the Programme Session Julian O’Neill Group for Dental Nurses Authors Rishma Shah and Therapists November2015 BOSNEWSSUPPLEMENT 3 8th International Orthodontic Congress Saturday 26 September 2015 Pre-Congress Course Contemporary Treatment for Missing Teeth in Growing Patients. Autotransplantation – The Natural Choice, The Royal College of Surgeons, London Dr Ewa Czochrowska and Dr Pawel Plakwicz What a great start to the 8th International Orthodontic Congress - a carefully presented inspirational course by Eva and Pawel following 20 years’ experience of working together as a passionate, if gently combative, expert team. Dr Pawel highlighted the importance of the venue since John Hunter completed the first recorded transplantation of a human canine tooth to grow within a cockerel’s comb – the results remain on display within the Hunterian Museum. -

Available Technologies, Applications and Benefits of Teleorthodontics. A

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Available Technologies, Applications and Benefits of Teleorthodontics. A Literature Review and Possible Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic 1,2, , 1,2, 1,2, 1,2 Cinzia Maspero * y , Andrea Abate y , Davide Cavagnetto y , Mohamed El Morsi , 1,2, 1,2, Andrea Fama z and Marco Farronato z 1 Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Milan, 20100 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (M.E.M.); [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (M.F.) 2 Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, 20100 Milan, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-338-334-4999 These authors contributed equally to this work. y These authors contributed equally to this work. z Received: 2 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 17 June 2020 Abstract: Background: COVID-2019 spread rapidly throughout the world from China. This infection is highly contagiousness, has a high morbidity, and is capable of evolving into a potentially lethal form of interstitial pneumonia. Numerous countries shut-down various activities that were considered “not essential.” Dental treatment was in this category and, at the time of writing, only non-deferrable emergencies are still allowed in many countries. Therefore, follow-up visits of ongoing active therapies (e.g., orthodontic treatment) must be handled taking special precautions. This literature review aims at reducing in-office appointments by providing an overview of the technologies available and their reliability in the long-distance monitoring of patients, i.e., teledentistry. -

3D Lingual Treatment with Suresmile and Tads Case Report

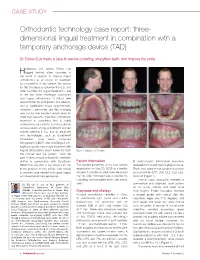

CASE STUDY Orthodontic technology case report: three- dimensional lingual treatment in combination with a temporary anchorage device (TAD) Dr. Edward Lin treats a case to resolve crowding, straighten teeth, and improve the smile istorically, the United States has Hlagged behind other countries in the world in regards to offering lingual orthodontics as an option for treatment to our patients. In my opinion, the reason for this discrepancy between the U.S. and other countries for lingual treatment is due to the two main challenges associated with lingual orthodontics: 1) difficult retie appointments for both patient and clinician, and 2) significantly longer appointments. However, I personally see this changing very quickly over the next several years for three main reasons: 1) esthetic orthodontic treatment is something that is highly desirable for our patients, 2) many patients are now aware of lingual treatment and are actively seeking it out, and 3) advances with technologies such as SureSmile® (OraMetrix), cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), and small lingual self- ligating brackets have made treatment with lingual orthodontics much easier for both Figure 1: Initial records 5/20/09 the clinician and the patient. Over the past 4 years, lingual orthodontic treatment utilized in combination with SureSmile/ Patient information III malocclusion. Periodontal evaluation CBCT has become a big adjunct for me This patient presented at his new patient revealed normal and healthy gingival tissue. in my practice. In this article, I will review examination on May 20, 2009 as a healthy There was some minor gingival recession a complex case treated with upper lingual 44-year, 1-month-old adult male. -

Company-Catalog-2016.Pdf

Table of Contents Welcome to Accutech 1……………....Selecting Your Laboratory 2………….Accutech History and Owners Accutech has been in business for over 30 years. We have now taken our passion of 3……………………………...Our Credentials building quality orthodontic appliances to an entirely different level in the orthodontic profession. 4………………………………..Client Benefits We continue to provide our extraordinary laboratory services, but we are now 5………………………Appliance Definitions offering orthodontic laboratory training and appliance design DVDs and books. These products are educational tools designed to help you fulfill your orthodontic laboratory 6………...…………………….Digital Services needs in a variety of ways. 7………………………………………..ClearBow Whether you are a current client or not, we invite you to explore this catalog and learn more about Accutech, the appliances we offer, and how you may start building 8 & 9………………………………...Retainers or rebuilding your ideal laboratory right away. 10...………………. Dr. Tremont Appliance Welcome! 11..……………………...Accutech Exclusives 12 & 13…………………….Spring Retainers 14………………….Appliance Components Accutech’s Performance Pledge 15……………………………..Acrylic Options Our products will be delivered on time, every time. 16 & 17…………………Invisible Retention We never take our Clients for granted. We follow the “Golden Rule” and treat 18…………………………………….Distalizers everyone with dignity and respect. 19………………………………...Active plates Accutech takes its responsibilities seriously. We acknowledge and quickly act upon 20 & 21…………………….Fixed appliances any concerns our Clients may have. 22………………………………………..Herbsts 23 & 24…………………………..Functionals We believe our Clients give above average care and treatment to their Patients so excellence and perfection goes into everything we do. 25…………………………Fixed/Removables 26 & 27…………………...Fixed Expanders The value of our products is based solely on our high level of quality and service. -

Current Orthodontic Theory and Treatment a Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by Cathy Seckman, RDH

Earn 1 CE credit This course was written for dentists, dental hygienists, and assistants. Current Orthodontic Theory and Treatment A Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by Cathy Seckman, RDH Abstract Learning Objectives: Author Profile The history of orthodontics began in ancient times, At the conclusion of this educational Cathy Hester Seckman, RDH, is a pediatric hygienist as well as an leading us to assume that humankind has always seen activity participants will be able to: indexer, writer, and novelist. She has worked in dentistry 33 years, in- value in an attractive smile. Orthodontics was first 1. Name and describe common cluding eight years in a practice that includes orthodontic treatment. recognized as a specialty in the 19th century. In mod- orthodontic appliances. She presents CE courses on topics including pediatric management, ern dentistry, with evidence-based practice gaining 2. List the actions of and purposes for nutrition, pre-natal to pre-school care, communication, and ground, treatment options address malocclusions as which different appliances are used. adolescent risk behaviors. She is a member of the American Dental well as problems in the transverse and vertical dimen- 3. Knowledgeably discuss invisible Hygienists Association and the Tri-County Ohio Dental Hygienists sions. Present-day practice includes the use of both orthodontics technology and use. Association. She can be reached at [email protected] . fixed and functional appliances. Dental hygienists 4. Customize oral hygiene recommen- with a working knowledge of orthodontic practice can dations for orthodontic appliances. Author Disclosure serve as valuable resources to patients and parents Cathy Hester Seckman has no potential conflicts of interest to from diagnosis to post-treatment questions. -

ORTHODONTIST by Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma

Special Report Top 10 Things You Should Know Before Choosing An ORTHODONTIST by Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma 405.364.4608 www.OSObraces.com Top 10 Things You Should Know Before Choosing an Orthodontist Introductory Letter from The Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma Dear Friend, If you’re here researching orthodontics for yourself, your children, or a loved one, you’re in the right place! Just as every set of teeth is different, every orthodontic practice or treatment process is dif- ferent. The Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma are the leaders in braces and orthodontic treatment options in Midwest City, Shawnee, and Norman, OK. Our orthodontic expertise includes a wide variety of techniques including: Invisalign©, SureSmile©, and even Self-Ligating Braces. Whatever your needs, we are sure we have the solution for you. Our technology allows our patients to get the same results as traditional orthodontists in fewer visits with an accelerated orthodontic treatment. Additionally, our consultative approach means our ortho- dontists explain all options available to you so you’re able to make an educated decision about your desired treatment plan. The Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma will personally meet with you during every appointment to ensure you’re happy with your results and to discuss ongoing options. We want you to be sure you’re making the best choice possible when it comes to orthodontic treatment. To help you choose the best orthodontics office for your needs, the team at The Orthodontic Special- ists put together “The Top 10 Things You Should Know Before Choosing Your Orthodontist.” Sincerely Your Team at Orthodontic Specialists of Oklahoma P.S.