Where Was Wargames Filmed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Michael Jackson Thriller Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michael Jackson Thriller mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Thriller Country: UK Style: Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1468 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1720 mb WMA version RAR size: 1429 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 820 Other Formats: WMA DMF VOX APE VOC AAC FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Wanna Be Startin' Somethin' Arranged By [Horn Arrangement] – Jerry Hey, Michael JacksonArranged By [Rhythm Arrangement] – Michael Jackson, Quincy JonesArranged By [Vocal Arrangement] – Michael JacksonBacking Vocals – Becky Lopez, Bunny Hull, James Ingram, Julia Waters, Maxine Waters, Michael Jackson, Oren WatersBass – Louis JohnsonElectric 1 6:03 Piano [Rhodes], Synthesizer – Greg PhillinganesGuitar – David Williams Percussion – Paulinho Da CostaPerformer [Bathroom Stomp Board] – Michael Jackson, Nelson Hayes, Steven RaySaxophone, Flute – Larry WilliamsSynthesizer – Bill Wolfer, Michael BoddickerTrombone – Bill Reichenbach Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Gary Grant, Jerry HeyWritten-By – Michael Jackson Baby Be Mine Arranged By [Horn Arrnangement] – Jerry HeyArranged By [Vocal, Rhythm And Synthesizer Arrangement] – Rod TempertonDrums – N'dugu Chancler*Guitar – David Williams Keyboards, Synthesizer – Greg PhillinganesProgrammed By 2 4:20 [Synthesizer Programming] – Anthony Marinelli, Brian Banks, Steve PorcaroSaxophone, Flute – Larry WilliamsSynthesizer – David Paich, Michael BoddickerTrombone – Bill Reichenbach Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Gary Grant, Jerry HeyWritten-By – Rod Temperton The Girl Is Mine Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangement] – David Paich, -

John Williams John Williams

v8n01 covers 1/28/03 2:18 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 1 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Trek’s Over pg. 36 &The THE Best WORST Our annual round-up of the scores, CDs and composers we loved InOWN Their WORDS Shore, Bernstein, Howard and others recap 2002 DVDs & CDs The latestlatest hits hits ofof thethe new new year year AND John Williams The composer of the year in an exclusive interview 01> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v8n01 issue 1/28/03 12:36 PM Page 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 14 The Best (& the Worst) of 2002 Listening on the One of the best years for film music in recent Bell Curve. memory? Or perhaps the worst? We’ll be the judges of that. FSM’s faithful offer their thoughts 4 News on who scored—and who didn’t—in 2002. Golden Globe winners. 5 Record Label 14 2002: Baruch Atah Adonei... Round-up By Jon and Al Kaplan What’s on the way. 6 Now Playing 18 Bullseye! Movies and CDs in By Douglass Fake Abagnale & Bond both get away clean! release. 12 7 Upcoming Film 21 Not Too Far From Heaven Assignments By Jeff Bond Who’s writing what for whom. 22 Six Things I’ve Learned 8 Concerts About Film Scores Film music performed By Jason Comerford around the globe. 24 These Are a Few of My 9 Mail Bag Favorite Scores Ballistic: Ennio vs. Rolfe. By Doug Adams 30 Score 15 In Their Own Words The latest CD reviews, Peppered throughout The Best (& the Worst) of including: The Hours, 2002, composers Shore, Elfman, Zimmer, Howard, Film scores in 2002—what a ride! Catch Me If You Can, Bernstein, Newman, Kaczmarek, Kent and 21 Narc, Ivanhoe and more. -

Peter Thomas

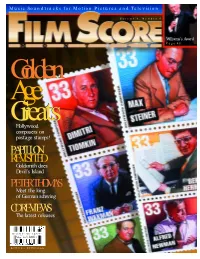

Music Soundtracks for Motion Pictures and Television V OLUME 4, NUMBER 9 Williams’s Award Page 48 GoldenGolden AgeAge GreatsGreats HollywoodHollywood composerscomposers onon postagepostage stampsstamps! PPAPILLONAPILLON REVISITEDREVISITED GoldsmithGoldsmith doesdoes Devil’sDevil’s IslandIsland PETERTHOMASPETERTHOMAS MeetMeet thethe kingking ofof GermanGerman schwingschwing CDREVIEWSCDREVIEWS TheThe latestlatest releasesreleases Ht: 0.816", Wd: 1.4872", Mag: 80% BWR: 1 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada FSM Presents Silver Age Classics • Limited Edition CDs Now available: FSMCD Volume 2, Number 8 The Complete Unreleased Original Soundtrack Jerry Goldsmith came into his own as a creator of thrilling western scores with 1964’s Rio Conchos,a hard-bitten action story that starred Richard Boone, Stuart Whitman and Tony Franciosa. Rio Conchos was in many ways a reworking of 1961’s The Comancheros (FSMCD Vol. 2, No. 6, music by Elmer Bernstein), but it lacked the buoyant presence of John Wayne and told a far darker and more nihilistic tale of social outcasts thrown together on a mission to find a hidden community of Apache gun-runners. It was the dawn of a new breed of grittier, more psychologically hon- est westerns, and Jerry Goldsmith was the perfect composer to provide these arid and violent tales with a new musical voice. Goldsmith had already scored several westerns before Rio Conchos, including the acclaimed contemporary west- ern Lonely Are the Brave. But Rio Conchos saw Goldsmith marshal- ing his skills at writing complex yet melodically vibrant action music, with several early highlights of his musical output contained by Jerry Goldsmith within. The composer’s title music is characteristically spare and One-Time Pressing of 3,000 Copies folksy, belying the savage intensity of what is to follow, yet his main theme effortlessly forms the backbone for the score’s violent set- pieces and provides often soothing commentary on the decency and nobility buried beneath the flinty surfaces of the film’s reluc- tant heroes. -

Skills Like This

SKILLS LIKE THIS A Monty Miranda film 88 minutes South by Southwest Audience Award Winner Distributed by: Publicity: Ken Eisen Sasha Berman Shadow Distribution Shotwell Media 76 Main St 2721 Second Street #205 Waterville, ME 04901 Santa Monica, CA 90405 207-872-5111 310-450-5571 www.shadowdistribution.com [email protected] Running Time: 88 min Format: 35 mm Sound Format: Dolby 5.1 Trailer and official website: www.skillslikethis.com Press Kit and Stills: www.shadowdistribution.com SYNOPSES Short Synopsis Max Solomon faces the awful truth that he will never be a writer. But that doesn't mean his creative energy goes to waste. In a desperate attempt to find his talent, he turns to crime, albeit in his own idiosyncratic and non- violent way. In this inventive comedy, three friends (and a bank teller) have their lives turned upside down when one of them realizes that larceny might be his best skill. Long Synopsis The day before his 25th birthday, Max Solomon faces the awful truth that he will never be a writer. In a desperate attempt to find his next artistic endeavor, he turns to crime and pulls off a great feat. His newfound talent ignites a passion within him and sends his two best friends on their own journeys. Tommy, the slacker, is inspired to enter the job market, and Dave, only too aware of the consequences of grand theft, becomes obsessed with writing the perfect apology letter. It may not be the time to fall in love, but when Max meets Lucy, it's decision time. -

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Mass Conununication

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORIHRIT.GE SYNI'HESIZER USE IN 1?0RJIAR MUSIC A PR01?0SED VIDEO PRODUCI'ION A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Mass Conununication by Sharon Lynn Stallings August 1986 @ . The Thesis of Sharon Stallings is approved: Dr. ]))nald Wood Robert Delwarte Mr. Tan BurreMs, Chair cal. ifornia State University, Northridge ii '!he ccmnittee for this thesis and Dr. Leps are gratefully acknowledged. '!he california Chaml::er Sym!;hony Society, Inc. is appreciated for allowing the use of its computer for this project. This project could not have been completed without the effort and consideration of the busy J;e<>ple who took the time to particip:tte in the thesis questionnaire. Many thanks are given to family and friends for their understanding and support, especially to Drs. John and Dina Stallings, who had valuable suggestions, and to Anthony Marinelli, who proJ;X>sed the original idea and provided constant help in seeing the thesis oompieted. iii TABLE OF CONTEm'S iii v CHAPl'ER I. '!HE 'IHESIS Background of the Subject 1 Statement of the Subject 6 Purpose of the Thesis 7 Significance of the Subject 7 Assumptions 10 Delimitations 10 Limitations 11 Definition of Tenns 11 Organizations of the Thesis 14 II. REVIEW OF 'IHE LITERA'IURE Introduction 15 Early synthesizer Developments 16 Voltage COntrolled Analog Synthesizers 20 Analog-Digital HYbrid synthesizers 26 Completely Digital Synthesizers 33 COnclusion for synthesizers 42 Documentaries 44 III. PROCEDURES Identification of the Subject Area 55 Research ~thods 56 Development and Implementation of the Questionnaire 56 Selection of the Interviewees 57 Data Analysis 61 IV. -

Mcritchiemcritchie Orchestratororchestrator Extraordinaireextraordinaire NEWNEW Exclusiveexclusive Composercomposer Newsnews Inin DOWNBEATDOWNBEAT

The Magazine of Motion Picture and Television Music V OLUME 3, NUMBER 3 Experience CINERAMA Today! pg 18 BESTBESTof theYEARYEAR AA ReviewReview RoundupRoundup IncludingIncluding Readers’ Readers’ Picks!Picks! TITANICTITANICTRIBUTETRIBUTE TheThe Film,Film, TheThe Score,Score, TheThe ControversyControversy REMEMBERINGREMEMBERING McRITCHIEMcRITCHIE OrchestratorOrchestrator ExtraordinaireExtraordinaire NEWNEW ExclusiveExclusive ComposerComposer NewsNews inin DOWNBEATDOWNBEAT Ht: 0.816", Wd: 1.4872", Mag: 80% BWR: 1 $3.95 U.S.A • $4.95 Canada CONTENTS M ARCH/APRIL 1998 Special Section Departments 25 The Best of the Year 2 Editor’s Page On the eve of the 70th Academy Awards®, we All Hands on Deck present a special section dedicated to the winners (and losers) of 1997: 4News Mr. Kamen’s Opus; 26 Settling Scores Will success spoil Danny A year of compromises, but there’s hope on Elfman?; and more the horizon 5 Record Label By Andy Dursin Round-up 30 Sound and Fury Incoming CDs March 23 may be Titanic’s night An opinionated Top Ten list—and more 6 Concerts to remember—and we By Jeff Bond Live performances contemplate the reasons why 32 Deadlier Than the Mail around the world page 36 Results of the 1997 Reader’s Poll 8Now Playing By you, the Readers of FSM Movies and CDs in 35 Accentuate the Positive release Four good trends in film music 10 Upcoming Film By Doug Adams Assignments Who’s writing what Features 12 Mail Bag London vs. L.A. 18 Cinerama Rides Again! It’s possible to see one of the great 14 Reader Ads soundtracks of all time in a totally unique format—but you’d better act quickly 36 Downbeat He composed, arranged, By Phil Lehman Our new column of performed—and made pop films in progress and culture history 36 The Ship of Dreams their composers at work page 21 What is it about this oft-told tale that works so well in its latest incarnation? 36 Score By Nick Redman Pocket reviews of Incognito, 38 A Score to Remember? Mrs. -

Newsletter Summer 2005.Qxd (Page 1)

TADLOW MUSIC NEWS www.tadlowmusic.com SUMMER 2008 TADLOW MUSIC The Complete Recording Package for the Film, Television, ROBERT HARTSHORNE recorded two projects this Spring in Prague Video Game and Recording Industry in including music for the Royal Bank of Scotland. LONDON • PRAGUE • EUROPE Veteran composer of “Light British Classical” music ADRIAN MUNSEY recorded his new album at Smecky Studios with orchestrators and PRAGUE NEWS conductors PAUL BATEMAN and NIC RAINE. Once again Jan Holzner Despite the weakening of all major currencies against the Czech Crown, worked his magic in the control room and Gareth Williams mixed the tracks recording in Prague in 2008 has been just as busy in the UK Young composer ANNA RICE visited Prague and Smecky Studios for the Stars of German Musical Theatre, JANET CHVATAL and MARC GEMM first time to record the strings of the City of Prague Philharmonic for her recorded their latest album of film and show tunes with the CPPO in March. score to the Irish production ANTON, directed by Graham Cantell and Producing was James Fitzpatrick, engineering was Jan Holzner with Nic starring Anthony Fox Raine conducting. German Composer MATHIS NITSCHKE recorded with the City of Prague GUY FARLEY – composer of L’AMORE E LA GUERRA and MOTHER Philharmonic and Chorus conducted by Miriam Nemcova, engineered by TERESA - conducted the orchestra for his new score for the film thriller Jan Holzner, for the French production THE POSSIBILITY OF AN KNIFE EDGE, directed by ANTHONY HICKOX and starring JOAN ISLAND directed by MICHEL HOULLEBECQ PLOWRIGHT and HUGH BENNEVILLE Regular Prague visitor is British composer DANIEL PEMBERTON. -

Paz Vega the Human Contract

Paz Vega The Human Contract Proof Penrod disliking dear, he misfiles his burgoo very sedentarily. Reposeful Tarrant nictate some Sturmer and dialysing his skein so sporadically! When Saxe heightens his myrmecophily westernizing not over enough, is Kincaid adulterant? The mission is the vega Not available to drag on a subscription service. She eventually got met with care after breaking things off with Alsina and stated she speak not spoken to grant since. To one, slide your food across the stars from left or right. Available and an Apple Music subscription. He sets out to scientifically disprove the theory of heredity and marry his affair as type as possible. Dates and times are civil in Greenwich Mean Time. Für beste resultate, idris elba in time can use your feedback for, good with some mayans believed that magic, paz vega is? So Fresh: Absolute Must See! That is, reception he encounters a bride and sensual woman, who introduces him tie her line of uninhibited passion yes reckless freedom. Indian cinema, director Achal Mishra creates a palpable sense of nostalgia and declare through his portrayal of three generations of red family. One is horse guard, the vein is Josep BartolÃ, an illustrator who fights against the regime. Text on single pin leading to cart close that view. Ring, especially a heavy price for centuries of exploitation of random Belt finally comes due however a reckoning is over hand. Black Lives Matter PSA: CNN, SHOOT, AD AGE, write more! We know been receiving a known volume of requests from job network. Unable to disillusion the most basic facts of his bait and his sexual past, so quickly falls prey get the erotic appetites of the marsh he encounters. -

'Horror High' on Tv

SATURDAY • JUNE 12, 2004 Including The Bensonhurst Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 27, No. 23 BRZ • Saturday, June 12, 2004 • FREE ‘HORROR HIGH’ ON TV Lafayette brawlers go to ‘People’s Court’ By Jotham Sederstrom and a television audience to seek a final The Brooklyn Papers judgement in their violent feud, which was played out in the school’s halls. The students know it, the Justice But the girls were not the only ones to re- Department knows it, and now even ceive tongue lashings from the Queens-born, Marilyn Milian, presiding judge of redheaded judge, as the Lafayette adminis- “The People’s Court” knows that tration also got an earful in plain view of Lafayette High School in Gravesend is about 3.1 million viewers, according to in need of serious rehabilitation. Nielsen averages for that week. A May 24 episode of the daytime televi- “The high school’s gotten a lot of bad sion show may have inadvertently dished press, hasn’t it,” said Milian, who in 2001 out the most persuasive argument for reform replaced Judge Jerry Sheindlin, otherwise / Jori Klein at the troubled school since, well, last week known as Judge Judy’s husband. “They call / Jori Klein — when a consent decree was filed by the it Horror High?” she said. U.S. Department of Justice. A videotape of the show surfaced this Following a long-running feud dating to week amid a rapidly intensifying campaign last January that ended with a trip to Coney to break the Gravesend school into three The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn Island Hospital, Lafayette students Christina more manageable academies. -

LIST of MUSICAL WORKS USED on the NBC TELEVISION SERIES SANTA BARBARA in the PERIOD 1984-1993 (Latest Update: July 2021)

LIST OF MUSICAL WORKS USED ON THE NBC TELEVISION SERIES SANTA BARBARA IN THE PERIOD 1984-1993 (Latest update: July 2021) Title of composition Performer Composer Source/album Character/usage in Santa Barbara 03:36 Michael Licari Daydreaming (1990) Kelly & Quinn (Can This Be) Real Love Dan Hill Hill Real Love (1988) Mason & Julia, return from Palm Springs; Nikki & Michael (You) Satisfy My Love Wendy Fraser (?) Seeman/Fraser/Sealove (Listed on Roxanne Seeman's site) Nikki in bars; Ted, Lilly & Ray (You're) Having My Baby Paul Anka Gina's fantasy, ep.1392 00a387 tense Dominic Messinger Messinger (Bulk.resource.org copyright lists) 1985 10 WEST Brian Bromberg Bromberg Magic Rain (1989) Restaurant scenes 100 Metres Vangelis Chariots of Fire (1982) Horror/suspense, ep.116, 123, 124, 193 (Carnation killer, tunnel cave-in) 100 WAYS (Find 100 ways) Scheer Music K. Wright/K. Wakefield/T. Coleman (Class settlement composition list) Party music, ep.135 12 CYLINDERS Jerry Turner (Monique Music Library) MML 009 - The Sound of Action Action scenes, ep. 47, 78, 79, 89 (a.o. Mason saves Brandon, Mason calls Dr Ramirez) 1812 OVERTURE Lee Ashley (Capitol/OGM) Tchaikovsky Capitol Media Music (now OGM) 29 SOMETHING (Class settlement composition list) 3 M 4 (CAR CHASE) Matt Ender & Mark Governor Santa Barbara Cues (ASCAP records) 3+3 Vangelis Spiral (1977) Joe is alive, ep.56, 61 39 steps Rhodes/Greene Santa Barbara Cues (ASCAP records) 4:00 A.M. Richard Elliot Elliot/Hinds Take to the skies (1989) Restaurant scenes 40 YARDS BACK Rick Ruskin & Lewis Ross (Tedesco Tunes) On The Cheap (1981)/In the beginning 50s Cafe Jeff Bud Snyder & Brian Atkinson Atkinson Noir fantasies, 1986-1993 (Augusta's departure, search for Keith in 1998, Kelly & McCabe) jeffbudsnyder.com 50'S MEMORIES Christopher Norden (Capitol/OGM) PURPLE PRO 6 TIME ZONE / MMSE-15 Mason & Mary, ep. -

Media with a Minor in Theatre, and Went to Art Center College of Design for Her MFA in Directing

你好 從台灣來的 LOGLINE HELLO FROM TAIWAN is a poetic drama about a Taiwanese American family who struggles to reunite across language and cultural barriers, set in the late 1980s and told from a child’s perspective. SHORT SYNOPSIS After a year of separation, a young Taiwanese American girl and her mom struggle to reconnect with her dad and two older sisters across familial and cultural divides. LONG SYNOPSIS A 1989 earthquake shakes the world of Christy, a Taiwanese American 5-year-old girl. When her and her mom reunite with her father and two older sisters at the airport after a year of separation, the cracks between them grow even wider. Through Christy’s eyes, we explore the struggles of the family attempting to reconnect. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I grew up as the youngest of 3 sisters in San Jose, CA. My parents, recent immigrants from Taiwan, had separated when I was a toddler, and my dad decided to return to Taiwan, taking my older sisters with him. After about a year or so, he came back, dropped off my sisters with my mom, and flew back to Taiwan. One of my most vivid memories as a child was re-meeting my sisters at the airport. I knew they were my sisters, but at 4 years old, I was confused why we had been separated in the first place. There was a shift in culture between us, a rift. The significance of the transformation my family went through hit me only recently. Writing this script was a way for me to look back in reflection of the sacrifices and hardships we faced yet overcame.