Revisiting the Invisible College: a Case Study of the Intellectual Structure and Social Process of Singularity Theory Research in Mathematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interviewed by T. Christine Stevens)

KENNETH A. ROSS JANUARY 8, 2011 AND JANUARY 5, 2012 (Interviewed by T. Christine Stevens) How did you get involved in the MAA? As a good citizen of the mathematical community, I was a member of MAA from the beginning of my career. But I worked in an “AMS culture,” so I wasn’t actively involved in the MAA. As of January, 1983, I had never served on an MAA committee. But I had been Associate Secretary of the AMS from 1971 to 1981, and thus Len Gillman (who was MAA Treasurer at the time) asked me to be MAA Secretary. There was a strong contrast between the cultures of the AMS and the MAA, and my first two years were very hard. Did you receive mentoring in the MAA at the early stages of your career? From whom? As a graduate student at the University of Washington, I hadn’t even been aware that the department chairman, Carl Allendoerfer, was serving at the time as MAA President. My first mentor in the MAA was Len Gillman, who got me involved with the MAA. Being Secretary and Treasurer, respectively, we consulted a lot, and he was the one who helped me learn the MAA culture. One confession: At that time, approvals for new unbudgeted expenses under $500 were handled by the Secretary, the Treasurer and the Executive Director, Al Wilcox. The requests usually came to me first. Since Len was consistently tough, and Al was a push-over, I would first ask the one whose answer would agree with mine, and then with a 2-0 vote, I didn’t have to even bother the other one. -

I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …

MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …......……………………. 2 Innovations ………………………………………………………..... 2 Scientific Highlights …..…………………………………………… 4 MSRI Experiences ….……………………………………………… 6 II. Programs …………………………………………………………………….. 13 III. Workshops ……………………………………………………………………. 17 IV. Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………………………………. 19 Papers by Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………… 21 V. Mathematics Education and Awareness …...………………………………. 23 VI. Industrial Participation ...…………………………………………………… 26 VII. Future Programs …………………………………………………………….. 28 VIII. Collaborations ………………………………………………………………… 30 IX. Papers Reported by Members ………………………………………………. 35 X. Appendix - Final Reports ……………………………………………………. 45 Programs Workshops Summer Graduate Workshops MSRI Network Conferences MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 This annual report covers MSRI projects and activities that have been concluded since the submission of the last report in May, 2005. This includes the Spring, 2005 semester programs, the 2005 summer graduate workshops, the Fall, 2005 programs and the January and February workshops of Spring, 2006. This report does not contain fiscal or demographic data. Those data will be submitted in the Fall, 2006 final report covering the completed fiscal 2006 year, based on audited financial reports. This report begins with a discussion of MSRI innovations undertaken this year, followed by highlights -

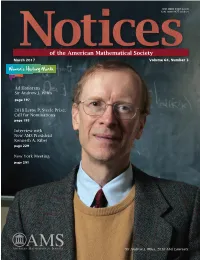

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

A Glimpse of the Laureate's Work

A glimpse of the Laureate’s work Alex Bellos Fermat’s Last Theorem – the problem that captured planets moved along their elliptical paths. By the beginning Andrew Wiles’ imagination as a boy, and that he proved of the nineteenth century, however, they were of interest three decades later – states that: for their own properties, and the subject of work by Niels Henrik Abel among others. There are no whole number solutions to the Modular forms are a much more abstract kind of equation xn + yn = zn when n is greater than 2. mathematical object. They are a certain type of mapping on a certain type of graph that exhibit an extremely high The theorem got its name because the French amateur number of symmetries. mathematician Pierre de Fermat wrote these words in Elliptic curves and modular forms had no apparent the margin of a book around 1637, together with the connection with each other. They were different fields, words: “I have a truly marvelous demonstration of this arising from different questions, studied by different people proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain.” who used different terminology and techniques. Yet in the The tantalizing suggestion of a proof was fantastic bait to 1950s two Japanese mathematicians, Yutaka Taniyama the many generations of mathematicians who tried and and Goro Shimura, had an idea that seemed to come out failed to find one. By the time Wiles was a boy Fermat’s of the blue: that on a deep level the fields were equivalent. Last Theorem had become the most famous unsolved The Japanese suggested that every elliptic curve could be problem in mathematics, and proving it was considered, associated with its own modular form, a claim known as by consensus, well beyond the reaches of available the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, a surprising and radical conceptual tools. -

Linking Together Members of the Mathematical Carlos Rocha, University of Lisbon; Jean Taylor, Cour- Community from the US and Abroad

NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Features Epimorphism Theorem Prime Numbers Interview J.-P. Bourguignon Societies European Physical Society Research Centres ESI Vienna December 2013 Issue 90 ISSN 1027-488X S E European M M Mathematical E S Society Cover photo: Jean-François Dars Mathematics and Computer Science from EDP Sciences www.esaim-cocv.org www.mmnp-journal.org www.rairo-ro.org www.esaim-m2an.org www.esaim-ps.org www.rairo-ita.org Contents Editorial Team European Editor-in-Chief Ulf Persson Matematiska Vetenskaper Lucia Di Vizio Chalmers tekniska högskola Université de Versailles- S-412 96 Göteborg, Sweden St Quentin e-mail: [email protected] Mathematical Laboratoire de Mathématiques 45 avenue des États-Unis Zdzisław Pogoda 78035 Versailles cedex, France Institute of Mathematicsr e-mail: [email protected] Jagiellonian University Society ul. prof. Stanisława Copy Editor Łojasiewicza 30-348 Kraków, Poland Chris Nunn e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter No. 90, December 2013 119 St Michaels Road, Aldershot, GU12 4JW, UK Themistocles M. Rassias Editorial: Meetings of Presidents – S. Huggett ............................ 3 e-mail: [email protected] (Problem Corner) Department of Mathematics A New Cover for the Newsletter – The Editorial Board ................. 5 Editors National Technical University Jean-Pierre Bourguignon: New President of the ERC .................. 8 of Athens, Zografou Campus Mariolina Bartolini Bussi GR-15780 Athens, Greece Peter Scholze to Receive 2013 Sastra Ramanujan Prize – K. Alladi 9 (Math. Education) e-mail: [email protected] DESU – Universitá di Modena e European Level Organisations for Women Mathematicians – Reggio Emilia Volker R. Remmert C. Series ............................................................................... 11 Via Allegri, 9 (History of Mathematics) Forty Years of the Epimorphism Theorem – I-42121 Reggio Emilia, Italy IZWT, Wuppertal University [email protected] D-42119 Wuppertal, Germany P. -

325458 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..23

Graduate Texts in Mathematics 288 Graduate Texts in Mathematics Series Editors Sheldon Axler San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA Kenneth Ribet University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Advisory Board Alejandro Adem, University of British Columbia David Eisenbud, University of California, Berkeley & MSRI Brian C. Hall, University of Notre Dame Patricia Hersh, University of Oregon J. F. Jardine, University of Western Ontario Jeffrey C. Lagarias, University of Michigan Eugenia Malinnikova, Stanford University Ken Ono, University of Virginia Jeremy Quastel, University of Toronto Barry Simon, California Institute of Technology Ravi Vakil, Stanford University Steven H. Weintraub, Lehigh University Melanie Matchett Wood, Harvard University Graduate Texts in Mathematics bridge the gap between passive study and creative understanding, offering graduate-level introductions to advanced topics in mathematics. The volumes are carefully written as teaching aids and highlight characteristic features of the theory. Although these books are frequently used as textbooks in graduate courses, they are also suitable for individual study. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/136 John Voight Quaternion Algebras 123 John Voight Department of Mathematics Dartmouth College Hanover, NH, USA This book is an open access publication. The Open Access publication of this book was made possible in part by generous support from Dartmouth College via Faculty Research and Professional Development funds, a John M. Manley Huntington Award, and Dartmouth Library Open Access Publishing. ISSN 0072-5285 ISSN 2197-5612 (electronic) Graduate Texts in Mathematics ISBN 978-3-030-56692-0 ISBN 978-3-030-56694-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56694-4 Mathematics Subject Classification: 11E12, 11F06, 11R52, 11S45, 16H05, 16U60, 20H10 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2021. -

2000 Steele Prizes

comm-steele.qxp 2/15/00 10:58 AM Page 477 2000 Steele Prizes The 2000 Leroy P. Steele Prizes were awarded at contributions in automata, the theory of games, the 106th Annual Meeting of the AMS in January lattices, coding theory, group theory, and qua- 2000 in Washington, DC. dratic forms. He has a rare gift for naming The Steele Prizes were established in 1970 in mathematical objects and for inventing useful honor of George David Birkhoff, William Fogg mathematical notations. His joy in mathematics is Osgood, and William Caspar Graustein and are clearly evident in all that he writes. Conway’s book endowed under the terms of a bequest from On Numbers and Games, London Math. Soc. Leroy P. Steele. The prizes are awarded in three Monographs, vol. 6, Academic Press, London, 1976, categories: for expository writing, for a research ISBN 0-12186-350-6, is a classic in its field and even paper of fundamental and lasting importance, and inspired a novel (Surreal Numbers by D. Knuth). In for cumulative influence extending over a career. the words of John Dawson’s review in Mathemat- The current award is $4,000 in each category. ical Reviews, “Overall, this book is a momentous The recipients of the 2000 Steele Prizes are addition to the mathematical literature: a new, JOHN H. CONWAY for Mathematical Exposition, exciting, and highly original theory is expounded BARRY MAZUR for a Seminal Contribution to Research by its creator in a style that is at once concise, (limited this year to algebra), and I. M. SINGER for literate, and delightfully whimsical.” An anony- Lifetime Achievement. -

Eugene Meetings (August 16-19)-Page 485

Eugene Meetings (August 16-19)-Page 485 Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 1984, Issue 235 Volume 31, Number 5, Pages 433-560 Providence, Rhode Island USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of the Notices was sent to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the Ameri· can Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and second announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meet ing. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society in Providence. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for ab stracts submitted for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcement and the list of organizers of special sessions. -

Annual Report 2016

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Maintaining Excellence in Mathematical Sciences Research 7 7 7 Advancing the Mathematics Profession 7 7 7 Supporting Mathematics Education at All Levels 7 7 7 Fostering Awareness and Appreciation of Mathematics Table of Contents Letter from the AMS President & AMS Executive Director ........ page 1 Highlights of the Year ...................................................................... page 2 Financial Review .............................................................................. page 12 Contributors ...................................................................................... page 15 JMMb photos courtesy Kate Awtry, JMM 2017 photographer. American Mathematical Society LETTER FROM THE AMS PRESIDENT & AMS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Colleagues and Friends of the AMS, It is our pleasure to send you the 2016 Annual Report of the American Mathematical Society, along with our sincere thanks to all of you who are members, volunteers, authors, donors, and staff. You play a key role in supporting the full spectrum of efforts by the Society to fulfill its mission to further the interests of mathematical research, scholarship, and education, serving the national and international community through publications, meetings, advocacy, and other programs. This report highlights many of our 2016 accomplishments, provides a financial report, and recognizes our many donors. We are especially interested in supporting students and early-career mathematicians and hope you will help inform those you know of the value of joining the AMS. Indeed, your donations support programs such as the Graduate Student Chapter Duke Photography. Todd, Photo by Les Robert L. Bryant Program. This program is available because of annual mathematician donations, and AMS President, 2015–2016 we hope you’ll encourage the establishment of a Graduate Student Chapter Program at your institution. We want to call your attention to two significant transitions in the senior leadership of our Society. -

The Arithmetic of Quaternion Algebras

The arithmetic of quaternion algebras John Voight [email protected] June 18, 2014 Preface Goal In the response to receiving the 1996 Steele Prize for Lifetime Achievement [Ste96], Shimura describes a lecture given by Eichler: [T]he fact that Eichler started with quaternion algebras determined his course thereafter, which was vastly successful. In a lecture he gave in Tokyo he drew a hexagon on the blackboard and called its vertices clock- wise as follows: automorphic forms, modular forms, quadratic forms, quaternion algebras, Riemann surfaces, and algebraic functions. This book is an attempt to fill in the hexagon sketched by Eichler and to augment it further with the vertices and edges that represent the work of many algebraists, geometers, and number theorists in the last 50 years. Quaternion algebras sit prominently at the intersection of many mathematical subjects. They capture essential features of noncommutative ring theory, number the- ory, K-theory, group theory, geometric topology, Lie theory, functions of a complex variable, spectral theory of Riemannian manifolds, arithmetic geometry, representa- tion theory, the Langlands program—and the list goes on. Quaternion algebras are especially fruitful to study because they often reflect some of the general aspects of these subjects, while at the same time they remain amenable to concrete argumenta- tion. With this in mind, we have two goals in writing this text. First, we hope to in- troduce a large subset of the above topics to graduate students interested in algebra, geometry, and number theory. We assume that students have been exposed to some algebraic number theory (e.g., quadratic fields), commutative algebra (e.g., module theory, localization, and tensor products), as well as the basics of linear algebra, topology, and complex analysis. -

Problem-Solving and Selected Topics in Number Theory: in the Spirit of the Mathematical Olympiads

Problem-Solving and Selected Topics in Number Theory Michael Th. Rassias Problem-Solving and Selected Topics in Number Theory In the Spirit of the Mathematical Olympiads Foreword by Preda Mihailescu( Michael Th. Rassias Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics University of Cambridge Cambridge CB3 0WB, UK [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-0494-2 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-0495-9 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0495-9 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 11-XX, 00A07 © Springer Science+ Business Media, LLC 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) To my father Themistocles Contents Foreword by Preda Mih˘ailescu ................................. ix Acknowledgments ............................................. xv 1 Introduction ............................................... 1 1.1 Basicnotions........................................... 1 1.2 Basic methods to compute the greatest common divisor . 4 1.2.1 TheEuclideanalgorithm........................... 5 1.2.2 Blankinship’smethod............................. -

Vortragsprogramm Mit Abstracts

VORTRAGSPROGRAMM MIT ABSTRACTS Gemeinsame Jahrestagung der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung und der Gesellschaft fu¨r Didaktik der Mathematik 25. – 30. M¨arz 2007 Humboldt-Universit¨at zu Berlin Impressum: Herausgeber Prof. Dr. Jurg¨ Kramer Institut fur¨ Mathematik · Humboldt-Universit¨at Berlin Unter den Linden 6 · 10099 Berlin Redaktionsschluss: 19. Februar 2007 Inhaltsverzeichnis Teil 1: Hauptvortr¨age 5 Vortragsprogramm . 6 Abstracts der Vortr¨age ......................... 7 Teil 2: Minisymposien 15 Zeiten und Orte der Minisymposien . 16 M 01: Automorphe Formen und Automorphe Darstellungen . 19 M 02: Internettechnologien und Informationskompetenz: Kollaborati- ves Arbeiten im Web . 25 M 03: Die Wahrscheinlichkeit kleiner Kugeln und das Quantisierungs- problem . 31 M 04: Differential geometry . 37 M 05: Diskrete Mathematik . 45 M 06: Formale L¨osungen von gew¨ohnlichen und partiellen Differential- gleichungen . 49 M 07: Geometry of random fractals . 57 M 08: Globale Analysis . 63 M 09: Mathematische Modelle komplexer Quantensysteme . 67 M 10: Multivariate dependence modelling using copulas – applications in finance . 79 M 11: Numerical methods in PDE-constrained optimization problems 85 M 12: PDEs and applications in geometry . 95 M 13: Recent developments for quasi-Newton methods . 101 M 14: Discrete geometry . 105 M 16: Stochastic models in population genetics: Coalescents, random trees and applications . 111 M 17: MITACS-MATHEON Minisymposium: Mathematics in the Life Sciences . 115 M 18: Computational and combinatorial algebraic topology . 121 M 19: Konvergenz adaptiver Diskretisierungsverfahren . 127 D 01: Mathematiktheater“ als Schulprojekt . 133 ” D 02: Computeralgebra und ihre Didaktik . 135 3 4 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS D 03: Computerunterstutzte¨ synthetische und analytische Raumgeo- metrie . 141 D 04: Computerwerkzeuge und Prufungen¨ . 145 D 05: Entwicklung des algebraischen Denkens .