Industrial Hygiene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE, UPDATED 2010 American College of Physicians A Position Paper 2010 Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care A Summary of a Position Paper Approved by the ACP Board of Regents, April 2010 What Are the Sources of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care? The Institute of Medicine defines disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive poorer quality care compared with nonminorities, even when access-related factors, such as insurance status and income, are controlled. The sources of racial and ethnic health care disparities include differences in geography, lack of access to adequate health coverage, communication difficulties between patient and provider, cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and lack of access to providers. In addition, disparities in the health care system contribute to the overall disparities in health status that affect racial and ethnic minorities. Why is it Important to Correct These Disparities? The problem of racial and ethnic health care disparities is highlighted in various statistics: • Minorities have less access to health care than whites. The level of uninsurance for Hispanics is 34% compared with 13% among whites. • Native Americans and Native Alaskans more often lack prenatal care in the first trimester. • Nationally, minority women are more likely to avoid a doctor’s visit due to cost. • Racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia are 30% less likely than whites to use antidementia medications. -

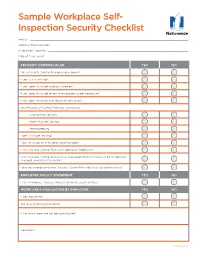

Sample Workplace Self- Inspection Security Checklist

Sample Workplace Self- Inspection Security Checklist Facility: ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Address/Work Location: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Assessment Done By: ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Date of Assessment: ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ SECURITY CONTROL PLAN YES NO Has a Security Control Plan been developed? If yes, is it in writing? If yes, does it include a policy statement? If yes, does it include review of employee incident exposure? If yes, does it include evaluation of work areas? Identification of Control Methods considered: Engineering Controls Work Practice Controls Recordkeeping Does it include training? Does it include an evacuation and floor plan? Is the Security Control Plan accessible to all employees? Is the Security Control Plan reviews and updated when a task has been added or changed, and at least annually? Have you coordinated your Security Control Plan with local law enforcement? EMPLOYER POLICY STATEMENT YES NO Is the Workplace Violence Policy statement clearly written? WORK AREA EVALUATION BY EMPLOYER YES NO If yes, how often? Are all areas being evaluated? If no, which areas are not being evaluated? Comments: Continued >> Loss Control Services Workplace Security Checklist CONTROL MEASURES -

TIN CAS Number

Common Name: TIN CAS Number: 7440-31-5 RTK Substance number: 1858 DOT Number: None Date: January 1986 Revision: April 2001 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------------- HAZARD SUMMARY WORKPLACE EXPOSURE LIMITS * Tin can affect you when breathed in. OSHA: The legal airborne permissible exposure limit * Contact can irritate the skin and eyes. (PEL) is 2 mg/m3 averaged over an 8-hour * Breathing Tin can irritate the nose, throat and lungs workshift. causing coughing, wheezing and/or shortness of breath. * Tin can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal NIOSH: The recommended airborne exposure limit is pain, headache, fatigue and tremors. 2 mg/m3 averaged over a 10-hour workshift. * Tin can cause "spots" to appear on chest x-ray with normal lung function (stannosis). ACGIH: The recommended airborne exposure limit is 3 * Tin may damage the liver and kidneys. 2 mg/m averaged over an 8-hour workshift. * High exposure can affect the nervous system. WAYS OF REDUCING EXPOSURE IDENTIFICATION * Where possible, enclose operations and use local exhaust Tin is a soft, white, silvery metal or a grey-green powder. It ventilation at the site of chemical release. If local exhaust is found in alloys, Babbitt and similar metal types, and is used ventilation or enclosure is not used, respirators should be as a protective coating and in glass bottle and can worn. manufacturing. * Wear protective work clothing. * Wash thoroughly immediately after exposure to Tin. REASON FOR CITATION * Post hazard and warning information in the work area. In * Tin is on the Hazardous Substance List because it is addition, as part of an ongoing education and training regulated by OSHA and cited by ACGIH and NIOSH. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide Volume 1: General PPE February 2003 F417-207-000 This guide is designed to be used by supervisors, lead workers, managers, employers, and anyone responsible for the safety and health of employees. Employees are also encouraged to use information in this guide to analyze their own jobs, be aware of work place hazards, and take active responsibility for their own safety. Photos and graphic illustrations contained within this document were provided courtesy of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Oregon OSHA, United States Coast Guard, EnviroWin Safety, Microsoft Clip Gallery (Online), and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. TABLE OF CONTENTS (If viewing this pdf document on the computer, you can place the cursor over the section headings below until a hand appears and then click. You can also use the Adobe Acrobat Navigation Pane to jump directly to the sections.) How To Use This Guide.......................................................................................... 4 A. Introduction.........................................................................................6 B. What you are required to do ..............................................................8 1. Do a Hazard Assessment for PPE and document it ........................................... 8 2. Select and provide appropriate PPE to your employees................................... 10 3. Provide training to your employees and document it ........................................ 11 -

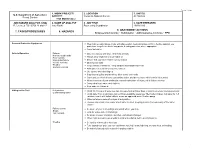

7. Tasks/Procedures 8. Hazards 9. Abatement

FS-6700-7 (11/99) 1. WORK PROJECT/ 2. LOCATION 3. UNIT(S) U.S. Department of Agriculture ACTIVITY Coconino National Forest All Districts Forest Service Trail Maintenance JOB HAZARD ANALYSIS (JHA) 4. NAME OF ANALYST 5. JOB TITLE 6. DATE PREPARED References-FSH 6709.11 and 12 Amy Racki Partnership Coordinator 10/28/2013 9. ABATEMENT ACTIONS 7. TASKS/PROCEDURES 8. HAZARDS Engineering Controls * Substitution * Administrative Controls * PPE Personal Protective Equipment Wear helmet, work gloves, boots with slip-resistant heels and soles with firm, flexible support, eye protection, long sleeve shirts, long pants, hearing protection where appropriate Carry first aid kit Vehicle Operation Fatigue Drive defensively and slow. Watch for animals Narrow, rough roads Always wear seatbelts and turn lights on Poor visibility Mechanical failure Ensure that you have reliable communication Vehicle Accients Obey speed limits Weather Keep vehicles maintained. Keep windows and windshield clean Animals on Road Anticipate careless actions by other drivers Use spotter when backing up Stay clear of gullies and trenches, drive slowly over rocks. Carry and use chock blocks, use parking brake, and do not leave vehicle while it is running Inform someone of your destination and estimated time of return, call in if plans change Carry extra food, water, and clothing Stop and rest if fatigued Hiking on the Trail Dehydration Drink 12-15 quarts of water per day, increase fluid on hotter days or during extremely strenuous activity Contaminated water Drink -

Healthcare Reform in Russia: Problems and William Tompson Prospects

OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 538 Healthcare Reform in Russia: Problems and William Tompson Prospects https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/327014317703 Unclassified ECO/WKP(2006)66 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 15-Jan-2007 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________ English text only ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Unclassified ECO/WKP(2006)66 HEALTHCARE REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 538 By William Tompson All Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's website at www.oecd.org/eco/working_papers text only English JT03220416 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format ECO/WKP(2006)66 ABSTRACT/RÉSUMÉ Healthcare Reform in Russia: Problems and Prospects This paper examines the prospects for reform of Russia’s healthcare system. It begins by exploring a number of fundamental imbalances that characterise the current half-reformed system of healthcare provision before going on to assess the government’s plans for going ahead with healthcare reform over the medium term. The challenges it faces include strengthening primary care provision and reducing the current over-reliance on tertiary care; restructuring the incentives facing healthcare providers; and completing the reform of the system of mandatory medical insurance. This paper relates to the OECD Economic Survey of the Russian Federation 2006 (www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/russia). JEL classification: I11, I12, I18 Keywords: Russia; healthcare; health insurance; competition; primary care; hospitalisation; pharmaceuticals; single payer; ***************** La reforme du système de santé en Russie: problèmes et perspectives La présente étude analyse les perspectives de réforme du système de santé en Russie. -

Understanding Asthma

Understanding Asthma The Mount Sinai − National Jewish Health Respiratory Institute was formed by the nation’s leading respiratory hospital National Jewish Health, based in Denver, and top ranked academic medical center the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Combining the strengths of both organizations into an integrated Respiratory Institute brings together leading expertise in diagnosing and treating all forms of respiratory illness and lung disease, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease (ILD) and bronchiectasis. The Respiratory Institute is based in New York City on the campus of Mount Sinai. njhealth.org Understanding Asthma An educational health series from National Jewish Health IN THIS ISSUE What Is Asthma? 2 How Does Asthma Develop? 4 How Is Asthma Diagnosed? 5 What Are the Goals of Treatment? 7 How Is Asthma Managed? 7 What Things Make Asthma Worse and How Can You Control Them? 8 Nocturnal Asthma 18 Occupational Asthma 19 Medication Therapy 20 Monitoring Your Asthma 29 Using an Action Plan 33 Living with Asthma 34 Note: This information is provided to you as an educational service of National Jewish Health. It is not meant as a substitute for your own doctor. © Copyright 1998, revised 2014, 2018 National Jewish Health What Is Asthma? This booklet, prepared by National Jewish Health in Denver, is intended to provide information to people with asthma. Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease — sometimes worrisome and inconvenient — but a manageable condition. With proper understanding, good medical care and monitoring, you can keep asthma well controlled. That’s our treatment goal at National Jewish Health: to teach patients and families how to manage asthma, so that they can lead full and productive lives. -

Five Keys to Safer Food Manual

FIVE KEYS TO SAFER FOOD MANUAL DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SAFETY, ZOONOSES AND FOODBORNE DISEASES FIVE KEYS TO SAFER FOOD MANUAL DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SAFETY, ZOONOSES AND FOODBORNE DISEASES INTRODUCTION Food safety is a significant public health issue nsafe food has been a human health problem since history was first recorded, and many food safety Uproblems encountered today are not new. Although governments all over the world are doing their best to improve the safety of the food supply, the occurrence of foodborne disease remains a significant health issue in both developed and developing countries. It has been estimated that each year 1.8 million people die as a result of diarrhoeal diseases and most of these cases can be attributed to contaminated food or water. Proper food preparation can prevent most foodborne diseases. More than 200 known diseases are transmitted through food.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has long been aware of the need to educate food handlers about their responsibilities for food safety. In the early 1990s, WHO developed the Ten Golden Rules for Safe Food Preparation, which were widely translated and reproduced. However, it became obvious that something simpler and more generally applicable was needed. After nearly a year of consultation with food safety expertsandriskcommunicators, WHOintroducedtheFive KeystoSaferFoodposterin2001.TheFive Keys toSaferFoodposterincorporatesallthemessagesoftheTen Golden Rules for Safe Food Preparation under simpler headings that are more easily remembered and also provides more details on the reasoning behind the suggested measures. The Five Keys to Safer Food Poster The core messages of the Five Keys to Safer Food are: (1) keep clean; (2) separate raw and cooked; (3) cook thoroughly; (4) keep food at safe temperatures; and (5) use safe water and raw materials. -

What the Public Thinks About Menatl Health and Mental Illness

What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and ~entaleI1lness A paper presented by Shirley A. Star, Senior Study Director National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago to the Annual Meeting The National Association for Mental Health, Inc. November 19, 1952 For the past two and a half years, the National Opinion Research Center has been engaged upon a pioneering study of the-American public's thinking in the field of mental health, under the joint sponsorship of the National Association for Mental Health and the National Institute of Mental Health, It is a vast and ambitious project, and I'm afraid that the title which has been assigned to my remarks about .the study is going to prove to be misleading in at least two ways. In the first place, and this must be obvious, both the title given me and the scope of the study cover Ear more ground than I could possibly present in the course of one afternoon. About all I can do today is hit a few of the high spots in public thinking and emphasize beforehand that the study aims to be inclusive. You can pretty well assume that it contains some information on just about any question in the area you might raise, even though I don't refer to many of them. So, as they say in the more enterprising shops--"If you don't see what you want, ask for it," In the second place, and this is more serious, I am in the em- barrassing position of having to stand here this afternoon and honestly- -2- admit that I don1t -know what the public thinks as yet. -

Guide to Developing the Safety Risk Management Component of a Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan

Guide to Developing the Safety Risk Management Component of a Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan Overview The Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan (PTASP) regulation (49 C.F.R. Part 673) requires certain operators of public transportation systems that are recipients or subrecipients of FTA grant funds to develop Agency Safety Plans (ASP) including the processes and procedures necessary for implementing Safety Management Systems (SMS). Safety Risk Management (SRM) is one of the four SMS components. Each eligible transit operator must have an approved ASP meeting the regulation requirements by July 20, 2020. Safety Risk Management The SRM process requires understanding the differences between hazards, events, and potential consequences. SRM is an essential process within a transit The Sample SRM Definitions Checklist can support agencies agency’s SMS for identifying hazards and analyzing, as- with understanding and distinguishing between these sessing, and mitigating safety risk. Key terms, as de- terms when considering safety concerns and to help ad- fined in Part 673, include: dress Part 673 requirements while developing the SRM • Event–any accident, incident, or occurrence. section of their ASP. • Hazard–any real or potential condition that can cause injury, illness, or death; damage to or loss of the facilities, equipment, rolling stock, or infra- structure of a public transportation system; or damage to the environment. • Risk–composite of predicted severity and likeli- hood of the potential effect of a hazard. • Risk Mitigation–method(s) to eliminate or re- duce the effects of hazards. Sample SRM Definitions Checklist The following is not defined in Part 673. However, transit Part 673 requires transit agencies to develop and imple- agencies may choose to derive a definition from other text ment an SRM process for all elements of its public provided in Part 673, such as: transportation system. -

Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 Credit Hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas

University of Florida College of Public Health & Health Professions Syllabus PHC 6521: Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 credit hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas Instructor Name: Dr. von Castel Room Number: FSHN 227 Phone Number: 352 Email Address: [email protected] *****PLEASE USE THIS NOT CANVAS Office Hours: by appointment via phone,conferences (in canvas) or Lync(Microsoft) Preferred Course Communications: email through ufl.edu Prerequisites None PURPOSE AND OUTCOME Public health nutrition involves the promotion of health through nutrition and the prevention of nutrition related disease in a population. It focuses on improving the food choices, dietary intake, and nutritional status at the community, regional, or national level. The public health nutrition professional works to assess nutritional problems and needs by considering environmental causes, identifying intervention points, developing policies and programs to intervene at those points, implementing the policies or programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Course Overview This course will provide an introduction to Public Health Nutrition and the role of the Public Health Nutrition professional. Emphasis will be on definition, identification and prevention of nutrition related disease, as well as improving health of a population by improving nutrition. Malnutrition will be discussed on a societal, economic, and environmental level. It will include the basics of nutritional biochemistry as it relates to malnutrition of a community and targeted intervention. Finally, it will review existing programs and policies, including strengths, weaknesses and areas for modification or new interventions. Relation to Program Outcomes MPH Competencies covered 1. Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems 2.