Great Massingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy

Appendix A Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Consultation Draft March 2015 1 Blank 2 Part One - Flooding and Flood Risk Management Contents PART ONE – FLOODING AND FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT ..................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 5 2 What Is Flooding? ........................................................................... 8 3. What is Flood Risk? ...................................................................... 10 4. What are the sources of flooding? ................................................ 13 5. Sources of Local Flood Risk ......................................................... 14 6. Sources of Strategic Flood Risk .................................................... 17 7. Flood Risk Management ............................................................... 19 8. Flood Risk Management Authorities ............................................. 22 PART TWO – FLOOD RISK IN NORFOLK .................................................. 30 9. Flood Risk in Norfolk ..................................................................... 30 Flood Risk in Your Area ................................................................ 39 10. Broadland District .......................................................................... 39 11. Breckland District .......................................................................... 45 12. Great Yarmouth Borough .............................................................. 51 13. Borough of King’s -

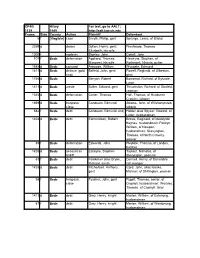

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020)

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020) MAP/LOT OWNER ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE PROP LOCATION I01/ 1/ / / LEAVITT, DONALD M & PAINE, TODD S 828 PARK AV BALTIMORE MD 21201 55 PINE ISLAND I01/ 1/A / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 54 PINE ISLAND I01/ 2/ / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 51 PINE ISLAND I01/ 3/ / / YOUNG, CHARLES FAMILY TRUST 401 STATE ST UNIT M501 PORTSMOUTH NH 03801 49 PINE ISLAND I01/ 4/ / / SALZMAN FAMILY REALTY TRUST 45-B GREEN ST JAMAICA PLAIN MA 02130 46 PINE ISLAND I01/ 5/ / / STONE FAMILY TRUST 36 VILLAGE RD APT 506 MIDDLETON MA 01949 43 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/ / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 41 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/A / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/B / / KERNER, GERALD 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 38 PINE ISLAND I01/ 7/ / / KERNER, LOUISE G 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 36 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 23 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/B / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 26 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/C / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 33 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/ / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 21 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 17 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/B / / FLYNN, MICHAEL P & LOUISE E 16 PINE ISLAND MEREDITH NH -

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE of REPORT to Inform Members of Th

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 24.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01172/F Mr Ian-Robert Bercham Barton Bendish Application Holly House Fincham Road Barton Permitted Bendish King's Lynn To provide a link corridor (Enclosed) between existing victorian conservatory and the out building. 27.05.2016 01.08.2016 16/01014/O Mr Geoff Simmons Bircham Application Whitegates Lynn Road Great Refused Bircham King's Lynn Outline Application: construction of a dwelling 05.05.2016 04.08.2016 16/00856/F Mr P Youel Boughton Application Kingston House Chapel Road Permitted Boughton Norfolk Single storey rear extension to dwelling 03.06.2016 21.07.2016 16/01040/F Mr & Mrs T Scrivener Boughton Application Church Farm Barn The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Construction of domestic garage 24.06.2016 18.08.2016 16/01175/F Mr & Mrs I Davis Boughton Application Hall Farm Cottage Mill Hill Road Permitted Boughton King's Lynn External wall insultation and render facing to exposed original cottage walls 10.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01095/F Mr Tim Williams Brancaster Application Bramble -

Impressive Country House Set in 63 Acres

Impressive country house set in 63 acres Little Massingham Manor, Little Massingham, Norfolk Freehold The Property and parkland in all extending Little Massingham Manor is an to about 63 acres. The house is impressive Arts & Crafts in a splendid rural situation country house set in a splendid surrounded by the picturesque rural location, approached by a rolling countryside of long drive and set in about 63 northwest Norfolk. As can be acres with mature gardens and seen from the floorplans the grounds, parkland and main house has spacious and woodland. Little Massingham well arranged accommodation Manor was built in 1907 by an with a magnificent main American Harley Street reception hall and four surgeon who decided to retire beautifully proportioned main to the area. After his death in reception rooms, all with fine 1916 and that of his son in 1919 views over the surrounding his widow sold the property to gardens, grounds and Mr Dixon Spain, a gentleman parkland. The bedroom farmer from the Fenland. The accommodation is divided house remained a happy family over two floors and situated in home, much loved by friends the grounds there is a separate and acquaintances. The family three bedroom cottage held many social events at the (Manor Cottage) as well as an manor and were well known in annexe at the entrance to the west Norfolk. drive. There is also a fine and substantial stable block. During World War II, the manor The history of the house has was requisitioned by the war been published and printed office and used by the RAF as privately and is available to an officers’ mess for the area. -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

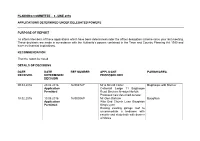

Great Massingham, Norfolk, PE32 2HN Grid Ref.: TF 797228 Map: Ordnance Survey – Explorer 250 Walking Time: 3 Hours Walk Summary

Roaming Around Massingham 5 miles Walk Information Start point: Outside The Dabbling Duck, 11 Abbey Road, Great Massingham, Norfolk, PE32 2HN Grid ref.: TF 797228 Map: Ordnance Survey – Explorer 250 Walking time: 3 hours Walk Summary This route takes in part of the Peddars Way, a National Trail, giving amazing vistas across the wonderful Norfolk countryside. This walk gives you the opportunity to discover a diversity of wildlife from common buzzards to common toads, brown hares to grey partridges. Keep your eyes peeled and who knows what you might see. Please note: • Dogs are welcome on this walking route but should at all times be kept on a lead and under close control. • At times this walk can be very muddy, especially along the Peddars Way. • Extreme care should be taken on the sections of the walk which involves walking along roads. Walk Notes 1 With your back to The 7 At a T-junction 8 At the road bear right. Dabbling Duck head right, Within the village of Great All along this route bear right, keeping passing the village sign and a Massingham there are a number are thick hedgerows Nut Wood on your right. duck pond on your left. Cross over of large ponds some of which which in the autumn Continue along this path 9 Shortly after passing two Lynn Lane and continue down were fish ponds for an 11th time are full of berries, until you reach the road. houses on your left, just Castleacre Road. century Augustinian Abbey. an important source of as the road bears to the right you food for many birds. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee. -

Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 418 HOUSING, ENGLAND The Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 Made - - - - 20th February 2004 Laid before Parliament 25th February 2004 Coming into force - - 17th March 2004 The First Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by sections 157(1)(c) and 3(a) of the Housing Act 1985(1) hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 17th March 2004. (2) In this Order “the Act” means the Housing Act 1985. Designated rural areas 2. The areas specified in the Schedule are designated as rural areas for the purposes of section 157 of the Act. Designated regions 3.—(1) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 1 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Forest of Dean. (2) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 2 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Rochford. (1) 1985 c. -

NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo

TRADES DIRECTORY. J NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo. Ingham, Norwich Kitteringham John, Tilney St. Law- ham Hall P. Itteringham, Aylsham R.S.O rence, Lynn Dyball E. T. 24 Fuller's hill, Yarmouth Hammond F. Barroway Drove, Downhm Knights Edwd. H. London rd. Harleston Dye Henry Samuel, 39 Audley street & Hammond Richard, West Bilney, Lynn Knott Charles, Ten Mile Bank, Downhm North Market road, Yarmouth & at Pentney, Swaffham Kybird J ames, Croxton, Thetford Earl Uriah, Coltishall, Norwich Hammond Robert Edward Hazel, Lade Frederick Wacton, Long Stratton Easter Frederick, Mileham, Swaffham Gayton, Lynn Lake Thomas, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Easter George, Blofield, Norwich Hammond William, Stow Bridge, Stow Lambert William Claydon, Wiggenhall Ebbs William, Alburgh, Harleston Bardolph, Downham St. Mary Magdalen, Lynn Edward Alfred, Griston, Thetford Hanton J ames, W estEnd street, Norwich Langham Alfred, Martham, Yarmouth Edwards Edward, Wretham, Great Harbord P. Burgh St. Margaret, Yarmth Lansdell Brothers, Hempnall, Norwich Hockham, Thetford Hardy Harry, Lake's end, Wisbech Lansdell Albert, Stratton St. Mary, Eggleton W. Great Ryburgh, Fakenham Harper Robt. Alfd. Halvergate, Nrwch Long Stratton R.S.O Eglington & Gooch, Hackford, Norwich Harrold Samuel, Church end, West Larner Henry, Stoke Ferry ~.0 Eke Everett, Mulbarton, Norwich Walton, Wisbech Last F. B. 93 Sth. Market rd. Yarmouth Eke Everet, Bracon Ash, Norwich Harrowven Henry, Catton, Norwich Lawes Harry Wm. Cawshm, Norwich Eke James, Saham Ton.ey, Thetford Hawes A. Terrington St. John, Wisbech Laws .Jo~eph, Spixworth, Norwich Eke R. Drayton, Norwich Hawes Robert Hilton, Terrington St. Leader James, Po!'ltwick, Norwich Ellis Charles, Palling, Norwich Clement, Lynn Leak T. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

1851 Census (Carried out on 30Th March) of Great Massingham and Little Massingham

1851 Census (carried out on 30th March) of Great Massingham and Little Massingham Transcribed from the original by Geoff Randall 1851 CENSUS RETURN FOR THE PARISHES OF GREAT MASSINGHAM & LITTLE MASSINGHAM In 1851 the Parishes were within the Parliamentary Division of West Norfolk, Superintendent Registrar’s District of Freebridge Lynn, Registrar’s District: Hillington. The Parishes included three enumeration districts - 1a, 1b & 2 as follows: Description of Enumeration District 1a All that part of the Parish of Great Massingham which lies to the South of highway leading from Weasenham to Grimstone including the Great Common the Royal Oak Inn and the field houses. Description of Enumeration District 1b All that part of the Parish which lays to the North of Great Massingham leading from the Weasenham to Grimstone, including the Rectory, the hill, the Abbey Farm and the xxxxx Inns. Description of Enumeration District 2 The whole of the Parish of Little Massingham including the Knights Wood, the Old Belt Wood, the Rectory and the Gipsy Bay Cottages. PART 1 1851 Census arranged according to Household Reference number. Page 2 of 62 Household Relationship to Head of Birth Name Marital Status Age Rank or Profession Birthplace Reference Household Year 1a/1 BLAXTER, Thomas Head Married 62 1789 Agricultural Labourer Great Massingham, Norfolk 1a/1 BLAXTER, Mary Wife Married 61 1790 Great Massingham, Norfolk 1a/1 BLAXTER, Harriet Daughter Unmarried 23 1828 Great Massingham, Norfolk 1a/2 SKIPPER, Charles Head Married 26 1825 Agricultural Labourer Weasenham, -

Cp40no1139cty.Pdf

CP40/ Hilary For text, go to AALT: 1139 1549 http://aalt.law.uh.edu Frame Side County Action Plaintiff Defendant 5 f [illegible] case Smyth, Phillip, gent Sprynge, Lewis, of Bristol 2259 d dower Dyllon, Henry, gent; Prestwode, Thomas Elizabeth, his wife 1000 f replevin Stonley, John Cottell, John 101 f Beds defamation Appliard, Thomas; Hawkyns, Stephen, of Margaret, his wife Rothewell, Nhants, pulter 1685 d Beds concord Atwoode, William Wyngate, Edmund 1411 d Beds detinue (gold Belfeld, John, gent Powell, Reginald, of Olbeston, ring) gent 1746 d Beds Benyon, Robert Bowstrad, Richard, of Byscote, Luton 1411 d Beds waste Butler, Edward, gent Thruckston, Richard, of Stotfeld, yeoman 1345 d Beds defamation Carter, Thomas Hall, Thomas, of Husburne Crawley, laborer 1869 d Beds trespass: Conquest, Edmund Adams, John, of Wilshampsted, close laborer 582 f Beds debt Conquest, Edmund, esq Helder alias Spycer, Edward, of Luton, husbandman 1428 d Beds debt Edmundson, Robert Browe, Reginald, of Meddylton Keynes, husbandman; Pokkyn, William, of Newport, husbandman; Skevyngton, Thomas, of North Crawley, weaver 85 f Beds defamation Edwards, John Pleyfote, Thomas, of London, butcher 1426 d Beds account as Estwyke, Stephen Taylour, Nicholas, of bailiff Stevyngton, yeoman 83 f Beds debt Fawkener alias Bryan, Dennell, Henry, of Dunstable, Richard, smith fish monger 1428 d Beds debt Fitzherbart, Anthony, Izard, John, alias Isaake, gent Michael, of Shitlington, yeoman 98 f Beds trespass: Fyssher, John, gent Pygett, Thomas, senior, of close Clophyll, husbandman;