1 on Emplacing: Reference, Coherence, Truth, and Paradoxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

Curriculum Vitae of Alvin Plantinga

CURRICULUM VITAE OF ALVIN PLANTINGA A. Education Calvin College A.B. 1954 University of Michigan M.A. 1955 Yale University Ph.D. 1958 B. Academic Honors and Awards Fellowships Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, 1968-69 Guggenheim Fellow, June 1 - December 31, 1971, April 4 - August 31, 1972 Fellow, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1975 - Fellow, Calvin Center for Christian Scholarship, 1979-1980 Visiting Fellow, Balliol College, Oxford 1975-76 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowships, 1975-76, 1987, 1995-6 Fellowship, American Council of Learned Societies, 1980-81 Fellow, Frisian Academy, 1999 Gifford Lecturer, 1987, 2005 Honorary Degrees Glasgow University, l982 Calvin College (Distinguished Alumni Award), 1986 North Park College, 1994 Free University of Amsterdam, 1995 Brigham Young University, 1996 University of the West in Timisoara (Timisoara, Romania), 1998 Valparaiso University, 1999 2 Offices Vice-President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1980-81 President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1981-82 President, Society of Christian Philosophers, l983-86 Summer Institutes and Seminars Staff Member, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Metaphysics, 1968 Staff member and director, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion, 1973 Director, National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar, 1974, 1975, 1978 Staff member and co-director (with William P. Alston) NEH Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion (Bellingham, Washington) 1986 Instructor, Pew Younger Scholars Seminar, 1995, 1999 Co-director summer seminar on nature in belief, Calvin College, July, 2004 Other E. Harris Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching (Danforth Foundation), 1968 Member, Council for Philosophical Studies, 1968-74 William Evans Visiting Fellow University of Otago (New Zealand) 1991 Mentor, Collegium, Fairfield University 1993 The James A. -

Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 4 200 YEARS OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY Article 5 2008 Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950 Mathieu Marion Université du Quéebec à Montréal, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Marion, Mathieu (2008) "Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of better understood as an attempt at foisting on it readers a particular Cognition, Logic and Communication set of misconceptions. To see this, one needs only to consider the title, which is plainly misleading. The Oxford English Dictionary gives as one August 2009 Volume 4: 200 Years of Analytical Philosophy of the possible meanings of the word ‘revolution’: pages 1-34 DOI: 10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 The complete overthrow of an established government or social order by those previously subject to it; an instance of MATHIEU MARION this; a forcible substitution of a new form of government. -

Logical Reasoning

updated: 11/29/11 Logical Reasoning Bradley H. Dowden Philosophy Department California State University Sacramento Sacramento, CA 95819 USA ii Preface Copyright © 2011 by Bradley H. Dowden This book Logical Reasoning by Bradley H. Dowden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. That is, you are free to share, copy, distribute, store, and transmit all or any part of the work under the following conditions: (1) Attribution You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author, namely by citing his name, the book title, and the relevant page numbers (but not in any way that suggests that the book Logical Reasoning or its author endorse you or your use of the work). (2) Noncommercial You may not use this work for commercial purposes (for example, by inserting passages into a book that is sold to students). (3) No Derivative Works You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. An earlier version of the book was published by Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, California USA in 1993 with ISBN number 0-534-17688-7. When Wadsworth decided no longer to print the book, they returned their publishing rights to the original author, Bradley Dowden. If you would like to suggest changes to the text, the author would appreciate your writing to him at [email protected]. iii Praise Comments on the 1993 edition, published by Wadsworth Publishing Company: "There is a great deal of coherence. The chapters build on one another. The organization is sound and the author does a superior job of presenting the structure of arguments. -

Using Russell's Theory of Descriptions to S

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú The Rise of Analytic Philosophy Scott Soames Seminar 6: From “On Denoting” to “On the Nature of Truth and Falsehood” Using Russell’s Theory of Descriptions to Solve Logical Puzzles One of Russell’s puzzles involves the law of classical logic called the law of the excluded middle. Here is his statement of the puzzle, which involves sentences (37a-c). “By the law of excluded middle, either “A is B” or “A is not B” must be true. Hence either “The present King of France is bald” or “The present King of France is not bald” must be true. Yet if we enumerated the things that are bald and the things that are not bald, we should not find the present King of France in either list. Hegelians, who love a synthesis, will probably conclude that he wears a wig.” (485) 1a. The present King of France is bald. b. The present King of France is not bald. c. Either the present King of France is bald or the present King of France is not bald. In the passage, Russell gives a reason for supposing that neither (1a) nor (1b) is true, which in turn seems to suggest that (1c) isn’t true. But that violates a law of classical logic that tells us that for every sentence S, ⎡Either S or ~S⎤ is true. Since Russell regarded the law as correct, he needed a way of defusing this apparent counterexample. The key to doing this lies in his general rule R for determining the logical form of sentences containing definite descriptions. -

Isabelle's Logics: FOL and ZF

ZF ∀ = Isabelle α λ β → Isabelle's Logics: FOL and ZF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory University of Cambridge [email protected] With Contributions by Tobias Nipkow and Markus Wenzel1 31 October 1999 1Markus Wenzel made numerous improvements. Philippe de Groote con- tributed to ZF. Philippe No¨eland Martin Coen made many contributions to ZF. The research has been funded by the EPSRC (grants GR/G53279, GR/H40570, GR/K57381, GR/K77051) and by ESPRIT project 6453: Types. Abstract This manual describes Isabelle's formalizations of many-sorted first-order logic (FOL) and Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory (ZF). See the Reference Manual for general Isabelle commands, and Introduction to Isabelle for an overall tutorial. Contents 1 Syntax definitions 1 2 First-Order Logic 3 2.1 Syntax and rules of inference ................... 3 2.2 Generic packages ......................... 4 2.3 Intuitionistic proof procedures .................. 4 2.4 Classical proof procedures .................... 9 2.5 An intuitionistic example ..................... 10 2.6 An example of intuitionistic negation .............. 12 2.7 A classical example ........................ 13 2.8 Derived rules and the classical tactics .............. 15 2.8.1 Deriving the introduction rule .............. 16 2.8.2 Deriving the elimination rule ............... 17 2.8.3 Using the derived rules .................. 18 2.8.4 Derived rules versus definitions ............. 20 3 Zermelo-Fraenkel Set Theory 23 3.1 Which version of axiomatic set theory? ............. 23 3.2 The syntax of set theory ..................... 24 3.3 Binding operators ......................... 26 3.4 The Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms .................. 29 3.5 From basic lemmas to function spaces .............. 32 3.5.1 Fundamental lemmas .................. -

Frege and the Logic of Sense and Reference

FREGE AND THE LOGIC OF SENSE AND REFERENCE Kevin C. Klement Routledge New York & London Published in 2002 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2002 by Kevin C. Klement All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infomration storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klement, Kevin C., 1974– Frege and the logic of sense and reference / by Kevin Klement. p. cm — (Studies in philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-415-93790-6 1. Frege, Gottlob, 1848–1925. 2. Sense (Philosophy) 3. Reference (Philosophy) I. Title II. Studies in philosophy (New York, N. Y.) B3245.F24 K54 2001 12'.68'092—dc21 2001048169 Contents Page Preface ix Abbreviations xiii 1. The Need for a Logical Calculus for the Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 3 Introduction 3 Frege’s Project: Logicism and the Notion of Begriffsschrift 4 The Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 8 The Limitations of the Begriffsschrift 14 Filling the Gap 21 2. The Logic of the Grundgesetze 25 Logical Language and the Content of Logic 25 Functionality and Predication 28 Quantifiers and Gothic Letters 32 Roman Letters: An Alternative Notation for Generality 38 Value-Ranges and Extensions of Concepts 42 The Syntactic Rules of the Begriffsschrift 44 The Axiomatization of Frege’s System 49 Responses to the Paradox 56 v vi Contents 3. -

Unity of Mind, Temporal Awareness, and Personal Identity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE THE LEGACY OF HUMEANISM: UNITY OF MIND, TEMPORAL AWARENESS, AND PERSONAL IDENTITY DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Philosophy by Daniel R. Siakel Dissertation Committee: Professor David Woodruff Smith, Chair Professor Sven Bernecker Associate Professor Marcello Oreste Fiocco Associate Professor Clinton Tolley 2016 © 2016 Daniel R. Siakel DEDICATION To My mother, Anna My father, Jim Life’s original, enduring constellation. And My “doctor father,” David Who sees. “We think that we can prove ourselves to ourselves. The truth is that we cannot say that we are one entity, one existence. Our individuality is really a heap or pile of experiences. We are made out of experiences of achievement, disappointment, hope, fear, and millions and billions and trillions of other things. All these little fragments put together are what we call our self and our life. Our pride of self-existence or sense of being is by no means one entity. It is a heap, a pile of stuff. It has some similarities to a pile of garbage.” “It’s not that everything is one. Everything is zero.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche “Galaxies of Stars, Grains of Sand” “Rhinoceros and Parrot” ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: Hume’s Appendix Problem and Associative Connections in the Treatise and Enquiry §1. General Introduction to Hume’s Science of Human Nature 6 §2. Introducing Hume’s Appendix Problem 8 §3. Contextualizing Hume’s Appendix Problem 15 §4. -

Abstract Consequence and Logics

Abstract Consequence and Logics Essays in honor of Edelcio G. de Souza edited by Alexandre Costa-Leite Contents Introduction Alexandre Costa-Leite On Edelcio G. de Souza PART 1 Abstraction, unity and logic 3 Jean-Yves Beziau Logical structures from a model-theoretical viewpoint 17 Gerhard Schurz Universal translatability: optimality-based justification of (not necessarily) classical logic 37 Roderick Batchelor Abstract logic with vocables 67 Juliano Maranh~ao An abstract definition of normative system 79 Newton C. A. da Costa and Decio Krause Suppes predicate for classes of structures and the notion of transportability 99 Patr´ıciaDel Nero Velasco On a reconstruction of the valuation concept PART 2 Categories, logics and arithmetic 115 Vladimir L. Vasyukov Internal logic of the H − B topos 135 Marcelo E. Coniglio On categorial combination of logics 173 Walter Carnielli and David Fuenmayor Godel's¨ incompleteness theorems from a paraconsistent perspective 199 Edgar L. B. Almeida and Rodrigo A. Freire On existence in arithmetic PART 3 Non-classical inferences 221 Arnon Avron A note on semi-implication with negation 227 Diana Costa and Manuel A. Martins A roadmap of paraconsistent hybrid logics 243 H´erculesde Araujo Feitosa, Angela Pereira Rodrigues Moreira and Marcelo Reicher Soares A relational model for the logic of deduction 251 Andrew Schumann From pragmatic truths to emotional truths 263 Hilan Bensusan and Gregory Carneiro Paraconsistentization through antimonotonicity: towards a logic of supplement PART 4 Philosophy and history of logic 277 Diogo H. B. Dias Hans Hahn and the foundations of mathematics 289 Cassiano Terra Rodrigues A first survey of Charles S. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Monochroidal Artist Or

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Monochroidal Artist or Noctuidae, Nematodes and Glaucomic Vision [Reading the Color of Concrete Comedy in Alphonse Allais’ Album Primo-Avrilesque (1897) through Philosopher Catherine Malabou’s The New Wounded (2012)] A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Emily Verla Bovino Committee in charge: Professor Jack Greenstein, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Sheldon Nodelman Professor Ricardo Dominguez Professor Rae Armantrout 2013 Copyright Emily Verla Bovino, 2013 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Emily Verla Bovino is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii EPIGRAPH PRÉFACE C’était en 18… (Ça ne nous rajeunit pas, tout cela.) Par un mien oncle, en récompense d’un troisième accessit d’instruction religieuse brillamment enlevé sur de redoutables concurrents, j’eus l’occasion de voir, avant qu’il ne partît pour l’Amérique, enlevé à coups de dollars, le célèbre tableau à la manière noire, intitulé: COMBAT DE NÈGRES DANS UNE CAVE, PENDANT LA NUIT (1) (1) On trouvera plus loin la reproduction de cette admirable toile. Nous la publions avec la permission spéciale des héritiers de l’auteur. L’impression que je ressentis à la vue de ce passionnant chef-d’oeuvre ne saurait relever d’aucune description. Ma destinée m’apparut brusquement en lettres de flammes. --Et mois aussi je serai peintre ! m’écriai-je en français (j’ignorais alors la langue italienne, en laquelle d’ailleurs je n’ai, depuis, fait aucun progrès).(1) Et quand je disais peintre, je m’entendais : je ne voulais pas parler des peintres à la façon dont on les entend les plus généralement, de ridicules artisans qui ont besoin de mille couleurs différentes pour exprimer leurs pénibles conceptions. -

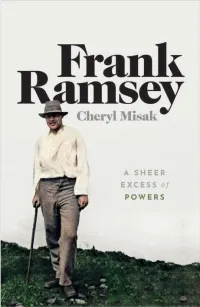

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Early Russell on Types and Plurals of Analytical Philosophy Kevin C

Journal FOR THE History Early Russell ON TYPES AND PlurALS OF Analytical Philosophy KeVIN C. Klement VOLUME 2, Number 6 In 1903, in The Principles of Mathematics (PoM), Russell endorsed an account of classes whereupon a class fundamentally is to be Editor IN Chief considered many things, and not one, and used this thesis to SandrA Lapointe, McMaster University explicate his first version of a theory of types, adding that it formed the logical justification for the grammatical distinction Editorial BoarD between singular and plural. The view, however, was short- Juliet Floyd, Boston University lived—rejected before PoM even appeared in print. However, GrEG Frost-Arnold, Hobart AND William Smith Colleges aside from mentions of a few misgivings, there is little evidence Henry Jackman, YORK University about why he abandoned this view. In this paper, I attempt to Chris Pincock, Ohio State University clarify Russell’s early views about plurality, arguing that they Mark TExtor, King’S College London did not involve countenancing special kinds of plural things RicharD Zach, University OF Calgary distinct from individuals. I also clarify what his misgivings about these views were, making it clear that while the plural understanding of classes helped solve certain forms of Russell’s PrODUCTION Editor paradox, certain other Cantorian paradoxes remained. Finally, Ryan Hickerson, University OF WESTERN OrEGON I aim to show that Russell’s abandonment of something like plural logic is understandable given his own conception of Editorial Assistant logic and philosophical aims when compared to the views and Daniel Harris, CUNY GrADUATE Center approaches taken by contemporary advocates of plural logic.