Investigating Behavior and Ecology of Aphaenogaster Swammerdami (Formicidae) in Selectively Logged Forest: 20 Years Later – a Happy Ant?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE Additional services for Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The wasps, bees and ants (Insecta: Vespida=Hymenoptera) from the Insect Limestone (Late Eocene) of the Isle of Wight, UK Alexander V. Antropov, Sergey A. Belokobylskij, Stephen G. Compton, Gennady M. Dlussky, Andrey I. Khalaim, Victor A. Kolyada, Mikhail A. Kozlov, Ksenia S. Perlieva and Alexandr P. Rasnitsyn Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh / Volume 104 / Issue 3-4 / May 2014, pp 335 - 446 DOI: 10.1017/S1755691014000103, Published online: 30 May 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1755691014000103 How to cite this article: Alexander V. Antropov, Sergey A. Belokobylskij, Stephen G. Compton, Gennady M. Dlussky, Andrey I. Khalaim, Victor A. Kolyada, Mikhail A. Kozlov, Ksenia S. Perlieva and Alexandr P. Rasnitsyn (2014). The wasps, bees and ants (Insecta: Vespida=Hymenoptera) from the Insect Limestone (Late Eocene) of the Isle of Wight, UK . Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 104, pp 335-446 doi:10.1017/S1755691014000103 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE, IP address: 146.231.3.1 on 31 Jul 2014 Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 104, 335–446, 2014 (for 2013) The wasps, bees and ants (Insecta: Vespida ¼ Hymenoptera) from the Insect Limestone (Late Eocene) of the Isle of Wight, UK Alexander V. -

Aphaenogaster Ant Nests

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Psyche Volume 2012, Article ID 840860, 12 pages doi:10.1155/2012/840860 Research Article Chemical Integration of Myrmecophilous Guests in Aphaenogaster Ant Nests Alain Lenoir,1 Quentin Chalon,1 Ana Carvajal,2 Camille Ruel,2 Angel´ Barroso,2 Toma´sLackner,ˇ 3 and Raphael¨ Boulay2, 4 1 Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l’Insecte, IRBI, UMR CNRS 7261, Universit´eFranc¸ois Rabelais, 37200 Tours, France 2 Estacion´ Biologica´ de Donana,˜ CSIC, 41092 Seville, Spain 3 Department of Forest Protection and Game Management, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Praha, Czech Republic 4 Departamento de Biolog´ıa Animal, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain Correspondence should be addressed to Alain Lenoir, [email protected] Received 13 October 2011; Accepted 7 December 2011 Academic Editor: Jean Paul Lachaud Copyright © 2012 Alain Lenoir et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Social insect nests provide a safe and favourable shelter to many guests and parasites. In Aphaenogaster senilis nests many guests are tolerated. Among them we studied the chemical integration of two myrmecophile beetles, Sternocoelis hispanus (Coleoptera: Histeridae) and Chitosa nigrita (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae), and a silverfish. Silverfishes bear low quantities of the host hydrocarbons (chemical insignificance), acquired probably passively, and they do not match the colony odour. Both beetle species use chemical mimicry to be accepted; they have the same specific cuticular hydrocarbon profile as their host. -

First Aphidiine Wasp from the Sakhalinian Amber

First aphidiine wasp from the Sakhalinian amber ELENA M. DAVIDIAN, MARYNA O. KALIUZHNA, and EVGENY E. PERKOVSKY Davidian E.M., Kaliuzhna M.O., and Perkovsky E.E. 2021. First aphidiine wasp from the Sakhalinian amber. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 66 (Supplement to 3): S59–S65. The first ichneumonoid aphidiine wasp species from Sakhalinian amber (middle Eocene) is described. Ephedrus rasnit- syni Davidian and Kaliuzhna sp. nov. іs the oldest named aphidiine female, the first fossil aphidiine from Asia, and the oldest named species of the Ephedrus. Ephedrus rasnitsyni Davidian and Kaliuzhna sp. nov. and the two fossil species of Ephedrus, i.e., Ephedrus primordialis from Baltic amber (late Eocene) and Ephedrus mirabilis from Camoins-les-Bains (early Oligocene), presumably belong to the Ephedrus plagiator species group of the subgenus Ephedrus sensu stricto, and new species differs from them in having a longer petiole and a rather long 3M vein that does not reach the forewing margin. It additionally differs from E. primordialis by having longer ovipositor sheaths. The new species is most similar to the extant Ephedrus validus and Ephedrus carinatus, from which it differs by the less elongated F1, absence of notauli, and by ovipositor sheaths that are 3.0 times as long as wide. Key words: Hymenoptera, Ichneumonoidea, Braconidae, Aphidiinae, Eocene, Oligocene, Baltic amber, Sakhalinian amber. Elena M. Davidian [[email protected]; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3804-4618], All-Russian Institute of Plant Protection (FSBSI VIZR), Podbelskogo, 3, St. Petersburg – Pushkin, 196608 Russian Federation. Maryna O. Kaliuzhna [[email protected]; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9265-0195], I.I. -

The Ant Aphaenogaster Dlusskyana Sp. Nov. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the Sakhalin Amber—The Earliest Described Species of an Extant Genus of Myrmicinae A

ISSN 00310301, Paleontological Journal, 2016, Vol. 50, No. 9, pp. 936–946. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2016. The Ant Aphaenogaster dlusskyana sp. nov. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the Sakhalin Amber—the Earliest Described Species of an Extant Genus of Myrmicinae A. G. Radchenko and E. E. Perkovsky Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, ul. Bogdana Khmel’nitskogo 15, Kiev, 01601, Ukraine email: [email protected], [email protected] Received April 10, 2015 Abstract—The earliest member of an extant ant genus of the subfamily Myrmicinae, Aphaenogaster dlussky ana sp. nov., from the Sakhalin amber (Russia, Middle Eocene, 43–47 Ma) is described. Fossil representa tives of the genus Aphaenogaster are critically analyzed and it is proposed to transfer many of these to the fossil morphotaxon Paraphaenogaster. The morphology, distribution, and possible evolutionary trends of the genus Aphaenogaster are reviewed and it is suggested that this genus appeared in the territory currently occupied by the Palearctic not later than the Early Eocene (over 50 Ma). Aphaenogaster dlusskyana can be considered the oldest described representative of an extant genus of the subfamily Myrmicinae, although earlier, as yet unde scribed, records of extant genera of Myrmicinae belong to the Early Eocene. Keywords: Myrmicinae, Aphaenogaster, Paraphaenogaster, ants, paleontology, taxonomy, evolution, Middle Eocene, Sakhalin amber DOI: 10.1134/S0031030116090136 INTRODUCTION (Danian, 56–59 Ma) to Middle Eocene (42–47 Ma). Dlussky (1988) -

APHAENOGASTER Aciculata Smith, F. 1874; See Under MESSOR

APHAENOGASTER aciculata Smith, F. 1874; see under MESSOR. acoreensis. Aphaenogaster senilis var. acoreensis Santschi, 1933a: 21 (q.) PORTUGAL (Azores Is). [Also described as new by Santschi, 1933c: 397, spelled acorensis.] Junior synonym of senilis: Yarrow, 1967: 26; Bolton, 1995b: 68; Boer, 2013: 81. aktaci. Aphaenogaster (Attomyrma) aktaci Kiran & Tezcan, in Kiran, et al. 2008: 690, fig. 1 (w.) TURKEY. Salata & Borowiec, 2018c: 5 (q.). Status as species: Kiran & Karaman, 2012: 16; Borowiec, L. 2014: 9; Salata & Borowiec, 2018c: 3. aegyptiaca Emery, 1878; see under MESSOR. afra. Aphaenogaster (Aphaenogaster) depilis var. afra Santschi, 1933c: 395, fig. 32 (w.m.) ALGERIA. Subspecies of depilis: Cagniant, 1968a: 142; Cagniant, 1970a: 415; Bolton, 1995b: 68. Status as species: Cagniant, 2006a: 196. alabamensis. Aphaenogaster treatae subsp. pluteicornis var. alabamensis Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, E.W. 1934: 10 (w.q.) U.S.A. (Alabama); unavailable (infrasubspecific) name. As unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Smith, M.R. 1951a: 798; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119. Declared as unavailable (infrasubspecific) name: Bolton, 1995b: 68. Material referred to treatae by Creighton, 1950a: 153; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1363; Bolton, 1995b: 68; Mackay & Mackay, 2017: 426. albisetosa Mayr, 1886; see under NOVOMESSOR. *amphioceanica. *Aphaenogaster amphioceanica De Andrade, 1995: 4, figs. 1, 3 (w.) DOMINICAN AMBER (Dominican Republic, Miocene). andrei Mayr, 1886; see under VEROMESSOR. angulata. Aphaenogaster (Attomyrma) famelica subsp. angulata Viehmeyer, 1922: 206 (w.) CHINA (Sichuan). Subspecies of famelica: Wheeler, W.M. 1930h: 62; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 131; Bolton, 1995b: 68; Guénard & Dunn, 2012: 39 (error?). Status as species: Tang, J., Li, et al. 1995: 50. anguliceps. Aphaenogaster (Deromyrma) longiceps subsp. -

Новый Род Жуков-Мягкотелок (Insecta: Coleoptera: Cantharidae: Cantharinae) Из Сахалинского Янтаря

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332571091 НОВЫЙ РОД ЖУКОВ-МЯГКОТЕЛОК (INSECTA: COLEOPTERA: CANTHARIDAE: CANTHARINAE) ИЗ САХАЛИНСКОГО ЯНТАРЯ Article · January 2019 DOI: 10.1134/S0031031X19030061 CITATIONS READS 0 5 2 authors, including: Sergey V. Kazantsev Insect Centre 66 PUBLICATIONS 179 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Fossil Coleoptera of Baltic amber View project All content following this page was uploaded by Sergey V. Kazantsev on 23 April 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ПАЛЕОНТОЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ЖУРНАЛ, 2019, № 3, с. 84–87 УДК 565.766.13:551.781.42 НОВЫЙ РОД ЖУКОВ-МЯГКОТЕЛОК (INSECTA: COLEOPTERA: CANTHARIDAE: CANTHARINAE) ИЗ САХАЛИНСКОГО ЯНТАРЯ © 2019 г. С. В. Казанцевa, *, Е. Э. Перковскийb, ** aИнсект-центр, Москва, Россия bИнститут зоологии им. И.И. Шмальгаузена, Киев, Украина *e-mail: [email protected] **e-mail: [email protected] Поступила в редакцию 14.03.2018 г. После доработки 29.10.2018 г. Принята к публикации 07.11.2018 г. Из среднеэоценового сахалинского янтаря описывается новый род и вид жуков-мягкотелок подсе- мейства Cantharinae, Cnathrion sakhalinense gen. et sp. nov. Это первый жук, описанный по имаго из сахалинского янтаря; обсуждается его предполагаемая афидофагия. DOI: 10.1134/S0031031X19030061 ВВЕДЕНИЕ стен из среднеэоценового сахалинского янтаря. И вот, наконец, при изучении инклюзов в саха- Вопрос о возрасте сахалинского янтаря долгое линском янтаре из коллекции Палеонтологиче- время оставался спорным. В.В. Жерихин (1978) ского ин-та им. А.А. Борисяка РАН (ПИН) один на основании косвенных данных определял его в из авторов обнаружил первого представителя широких пределах – от палеоцена (даний, 56– Cantharidae. -

Taxonomic Review of the Genus Aphaenogaster (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae) in Korea with a Newly Recorded Species

Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 13 (2020) 470e474 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/japb Short Communication Taxonomic review of the genus Aphaenogaster (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae) in Korea with a newly recorded species Dong Oh Shin a, Sun Woo Yoon a, Dong Pyeo Lyu b,* a Pureunsol Ant Research Center, Dalseo-gu, Daegu 42814, South Korea b Department of Forest sciences, Sangji University, Wonju, Gangwon 26339, South Korea article info abstract Article history: The species of the Aphaenogaster lepida Wheeler, 1930 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) were recorded in Received 17 March 2020 Korea for the first time. Morphological characteristics of workers of this species and a taxonomic key of Received in revised form species to the Korean Aphaenogaster are provided. 13 May 2020 Ó 2020 National Science Museum of Korea (NSMK) and Korea National Arboretum (KNA), Publishing Accepted 21 May 2020 Services by Elsevier. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http:// Available online 1 June 2020 creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Keywords: Formicidae Hymenoptera Korea Myrmicinae Taxonomic key Introduction Material and methods Genus Aphaenogaster is a genus of elongate, slender ants, which The specimens examined in this study were deposited at Sangji are very fast and agile in the field. Most species nest in the soil University, South Korea. Specimens were photographed using a under stones or logs; some of the desert species nest in the soil with Leica DMS 1000 microscope and an S8AP0 microscope (Leica the nest entrance surrounded by pebbles. -

A New Species of the Ant Genus Aphaenogaster Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Iran

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY Volume 5, 45–51, 2013 ISSN 1985-1944 © KADRI KI RAN , HELEN AL I PANA H , OM I D PA K N I A A new species of the ant genus Aphaenogaster Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Iran KADRI KI RAN 1*, HELEN AL I PANA H 2, OM I D PA K N I A 3 ∗Corresponding author 1Trakya University, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology 22030 Edirne, TURKEY Corresponding author's email: [email protected] 2Insect Taxonomy Research Department, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection (IRIPP), P. O. Box 1454, Tehran 19395, IRAN 3University of Ulm, Institute for Experimental Ecology, Albert Einstein Allee 11, 89069 Ulm, GERMANY ABSTRACT. A new species, Aphaenogaster iranica Kiran et Alipanah, sp. nov., is described from Iran. This species, belonging to the rothneyi group, is measured, illustrated and compared with other species of the group. Additionally, a key to workers of Aphaenogaster species from Iran is prepared. Keywords: ants, Formicidae, Aphaenogaster, taxonomy, Iran, new species. INTRODUCTION the splendida group and rothneyi group can be identified at first glance by their slender bodies Aphaenogaster is a speciose genus found and long extremities, their elongated heads and everywhere except the Afrotropics. The genus has fine sculpture. On the other hand, species of the 214 extant and 19 extinct species in the world, of rothneyi group differ from the splendida group which 121 species and 23 subspecies are found by their funicular segments which are three times in the Palaearctic Region (Collingwood 1961, longer than broad (maximum two times longer Cagniant 1996, Bolton et al. -

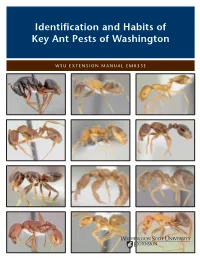

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals. -

Biology and Ecology of Ants of the Genus Aphaenogaster in Florida

BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY OF ANTS OF THE GENUS APHAENOGASTER IN FLORIDA By JOHN F. CARROLL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1975 c IB ACKNOWLEDGMENTS is I am grateful for the assistance rendered me by several people during this study. Particular thanks are due Dr. W. H. Whitcomb, chairman of my supervisory committee, for his suggestions and encour- agement, and to committee members Drs. W. F. Buren, T. C. Emmel, L. C. Kuitert, and J. E. Lloyd for their assistance in preparing this dissertation. I wish to thank Dr. W. F. Buren for identifying numerous ant specimens and for his aid in the systematics portion of my research. Other individuals to whom I am indebted for identifications are: H. A. Denmark, mites; Dr. T. J. Walker, myrmeccphilous crickets; G. B. Edwards, spiders; Dr. J. W. Kimbrough, fungi. Additionally thanks are due Dr. A. P. Bhatkar, T. M. Neal, and D. P. Wojcik for collecting specimens for me or loaning specimens to me for examination. I am also grateful to Dr. P. S. Callahan and J. C. E. Nicker son for allowing me to examine the ants collected in their light trap study. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT vi INTRODUCTION 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 3 Distribution 3 Economic Importance 3 Ecology and Biology 5 MATERIALS AND METHODS 15 Field Studies 15 Detection of Colonies 15 Collecting Trips 17 Collection of Colonies 18 Dissection of Colonies 20 Field Observations 21 Foraging Success 22 Laboratory Studies 23 Maintenance of Colonies 23 Determination of Stadial Duration ... -

Zootaxa: Australian Ants of the Genus Aphaenogaster (Hymenoptera

Zootaxa 1677: 25–45 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Australian ants of the genus Aphaenogaster (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) STEVEN O SHATTUCK CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Australian species of the myrmicine ant genus Aphaenogaster Mayr are revised. Eight species are recognised, four of which are described as new. The species include barbara sp. n., barbigula Wheeler (for which a lectotype is desig- nated), kimberleyensis sp. n., longiceps (Smith) (with its newly recognised synonym, flava Emery), mediterrae sp. n., poultoni Crawley, pythia Forel (for which a neotype is designated) and reichelae sp. n. Aphaenogaster is widely distrib- uted across eastern and southern Australia (except Tasmania), with isolated populations in northern Northern Territory and northern Western Australia. Species occur in a range of habitats from rainforests through open woodlands and can be of significant economic importance because of damage caused by their nests. Key words: Australia, Formicidae, Hymenoptera, new species, lectotype, neotype, Aphaenogaster Introduction The distinctive nests of Australian Aphaenogaster ants are often the first indication of their presence. These nests can be very dense and when in sandy soils, individual entrances can be large, deep cones or bores (up to 4 cm in diameter and 30 cm deep) with large mounds of loose dirt. This style of nest has resulted in these ants being known as “funnel ants.” In some cases nests can be so dense and extensive that they severely affect soil structure, resulting in a loose and fragile surface which easily collapses under foot. -

Zootaxa, Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Aphaenogaster

Zootaxa 655: 1–12 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 655 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A revision of the Aphaenogaster phalangium complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae) JOHN T. LONGINO* & STEFAN COVER** * The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington 98505, USA1; [email protected] ** The Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard, MA 02138, USA 1. To whom correspondence should be addressed. Abstract The Aphaenogaster phalangium complex is a lineage of rainforest ants endemic to Central Amer- ica. The complex is revised and interpreted as two parapatric species, A. phalangium and A. arane- oides, with extensive geographic variation. Character variation is discordant within species, but in some cases appears to vary in parallel between the two species, such that both species vary the same way in montane versus lowland sites. Aphaenogaster inermis Forel 1899, A. nitidiventris Forel 1912, and A. canalis Enzmann 1947 are synonymized under A. phalangium Emery 1890; and A. brevicollis Forel 1899 is synonymized under A. araneoides Emery 1890. The complex lacks winged queens and instead has ergatoid queens with enlarged postpetiole and gaster. Key words: Aphaenogaster phalangium, Aphaenogaster araneoides, Formicidae, geographic vari- ation Introduction Forested habitats of Central America are home to ants of the Aphaenogaster phalangium complex. Within the context of the New World Aphaenogaster fauna, the workers of the phalangium complex are uniquely identified by a combination of head and propodeum characters. The portion of the head posterior to the eyes is drawn out and tapers to a strongly constricted neck, beyond which the head flares out into a pronounced collar.