Media Framing of the Movement for Black Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

The News Media Industry Defined

Spring 2006 Industry Study Final Report News Media Industry The Industrial College of the Armed Forces National Defense University Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. 20319-5062 i NEWS MEDIA 2006 ABSTRACT: The American news media industry is characterized by two competing dynamics – traditional journalistic values and market demands for profit. Most within the industry consider themselves to be journalists first. In that capacity, they fulfill two key roles: providing information that helps the public act as informed citizens, and serving as a watchdog that provides an important check on the power of the American government. At the same time, the news media is an extremely costly, market-driven, and profit-oriented industry. These sometimes conflicting interests compel the industry to weigh the public interest against what will sell. Moreover, several fast-paced trends have emerged within the industry in recent years, driven largely by changes in technology, demographics, and industry economics. They include: consolidation of news organizations, government deregulation, the emergence of new types of media, blurring of the distinction between news and entertainment, decline in international coverage, declining circulation and viewership for some of the oldest media institutions, and increased skepticism of the credibility of “mainstream media.” Looking ahead, technology will enable consumers to tailor their news and access it at their convenience – perhaps at the cost of reading the dull but important stories that make an informed citizenry. Changes in viewer preferences – combined with financial pressures and fast paced technological changes– are forcing the mainstream media to re-look their long-held business strategies. These changes will continue to impact the media’s approach to the news and the profitability of the news industry. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

African Americans' Response to Police Brutality: the Black Lives

Mohamed Khider University of Biskra Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of Foreign Languages MASTER THESIS Letters and Foreign Languages English Language Literature and Civilization Submitted and Defended by: Imane CHEHABA African Americans’ Response to Police Brutality: The Black Lives Matter Strategy and Agenda Board of Examiners : Dr Salim KERBOUA PHD University of Biskra Superviser Mr Abdelnacer BENADELRREZAK MAB University of Biskra Examiner Mrs Asmaa CHRIET MAB University of Biskra Examiner Mrs Maymouna HADDAD MAB University of Biskra Chairperson Academic Year : 2018-2019 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my siblings, Karim, Yacine and Doudi. To my grandparents, my uncle and my auntie who have always been a constant source of encouragement and support during the challenges of my whole college life. To my bestie Malak Rahmouni whom I am truly grateful for having in my life. This work is also dedicated to my mother. Mom, thank you for the unconditional love that you provide me with, thank you for every single sacrifice. I dedicate this work to my teachers and my friends. Thank you everyone i Acknowledgement This work would not have been possible without the efforts of each one of my teachers. I am especially indebted to my teacher and supervisor Dr.Salim Kerboua. From this platform, I would like to thank him for developing my interest in the topic and for providing me with beneficial sources and guidance. I am grateful to all of those with whom I have had the honor to work during this journey. I would like to thank all of my teachers for providing me with extensive academic guidance. -

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and The

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 Black Belt Press The ONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT M and the WOMEN WHO STARTED IT __________________________ The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson __________________________ Mrs. Jo Ann Gibson Robinson Black women in Montgomery, Alabama, unlocked a remarkable spirit in their city in late 1955. Sick of segregated public transportation, these women decided to wield their financial power against the city bus system and, led by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (1912-1992), convinced Montgomery's African Americans to stop using public transportation. Robinson was born in Georgia and attended the segregated schools of Macon. After graduating from Fort Valley State College, she taught school in Macon and eventually went on to earn an M.A. in English at Atlanta University. In 1949 she took a faculty position at Alabama State College in Mont- gomery. There she joined the Women's Political Council. When a Montgomery bus driver insulted her, she vowed to end racial seating on the city's buses. Using her position as president of the Council, she mounted a boycott. She remained active in the civil rights movement in Montgomery until she left that city in 1960. Her story illustrates how the desire on the part of individuals to resist oppression — once *it is organized, led, and aimed at a specific goal — can be transformed into a mass movement. Mrs. T. M. Glass Ch. 2: The Boycott Begins n Friday morning, December 2, 1955, a goodly number of Mont- gomery’s black clergymen happened to be meeting at the Hilliard O Chapel A. -

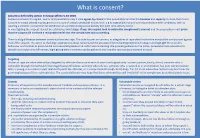

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

The Perimetric Boycott: a Tool for Tobacco Control Advocacy N Offen, E a Smith, R E Malone

272 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2005.011247 on 26 July 2005. Downloaded from RESEARCH PAPER The perimetric boycott: a tool for tobacco control advocacy N Offen, E A Smith, R E Malone ............................................................................................................................... Tobacco Control 2005;14:272–277. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011247 Objectives: To propose criteria to help advocates: (1) determine when tobacco related boycotts may be useful; (2) select appropriate targets; and (3) predict and measure boycott success. See end of article for Methods: Analysis of tobacco focused boycotts retrieved from internal tobacco industry documents authors’ affiliations websites and other scholarship on boycotts. ....................... Results: Tobacco related boycotts may be characterised by boycott target and reason undertaken. Most Correspondence to: boycotts targeted the industry itself and were called for political or economic reasons unrelated to tobacco Naphtali Offen, disease, often resulting in settlements that gave the industry marketing and public relations advantages. Department of Social and Even a lengthy health focused boycott of tobacco industry food subsidiaries accomplished little, making Behavioral Sciences Box demands the industry was unlikely to meet. In contrast, a perimetric boycott (targeting institutions at the 0612, University of California, San Francisco, perimeter of the core target) of an organisation that was taking tobacco money mobilised its constituency CA 94143, USA; and convinced the organisation to end the practice. [email protected] Conclusions: Direct boycotts of the industry have rarely advanced tobacco control. Perimetric boycotts of Received 25 January 2005 industry allies offer advocates a promising tool for further marginalising the industry. Successful boycotts Accepted 13 April 2005 include a focus on the public health consequences of tobacco use; an accessible point of pressure; a mutual ...................... -

Constitutional Law - Freedom of Association and the Political Boycott Elaine Cohoon

Campbell Law Review Volume 5 Article 4 Issue 2 Spring 1983 January 1983 Constitutional Law - Freedom of Association and the Political Boycott Elaine Cohoon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Elaine Cohoon, Constitutional Law - Freedom of Association and the Political Boycott, 5 Campbell L. Rev. 359 (1983). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Cohoon: Constitutional Law - Freedom of Association and the Political Boy NOTES CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION AND THE POLITICAL BOYCOTT-N.A.A.C.P. v. CLAIBORNE HARDWARE CO., 102 S. Ct. 3409 (1982). INTRODUCTION When several people with a common goal join together to achieve that goal, are their actions conspiratal or constitutionally protected? When that concerted action leads to economic losses, is the action unfair anti-competition or merely effective political per- suasion? The courts have been troubled by this dichotomy for years, switching sides with confusing regularity. Civil or criminal conspiracy has been severely punished because of the greater threat offered by the concerted actions of a group.' On the other hand, "the practice of persons sharing common views banding to- gether to achieve a common end is deeply embedded in the Ameri- can political process.''2 Even when there is no question of criminal or civil conspiracy, concerted actions have been prohibited for other reasons. -

The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest

Page 33 Chapter 8 The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest espite the many arguments made against it, the Stamp Act was passed and scheduled to be enforced on November 1, 1765. The colonists found ever more vigorous and violent ways to D protest the Act. In Virginia, a tall backwoods lawyer, Patrick Henry, made a fiery speech and pushed five resolutions through the Virginia Assembly. In Boston, an angry mob inspired by Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty destroyed property belonging to a man rumored to be a Stamp agent and to Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In New York, delegates from nine colonies, sitting as the Stamp Act Congress, petitioned the King and Parliament for repeal. In Philadelphia, New York, and other seaport towns, merchants pledged not to buy or sell British goods until the hated stamp tax was repealed. This storm of resistance and protest eventually had the desired effect. Stamp sgents hastily resigned their Commissions and not a single stamp was ever sold in the colonies. Meanwhile, British merchants petitioned Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. In 1766, the law was repealed but replaced with the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had the right to make laws binding on the colonies "in all cases whatsoever." The methods used to protest the Stamp Act raised issues concerning the use of illegal and violent protest, which are considered in this chapter. May: Patrick Henry and the Virginia Resolutions Patrick Henry had been a member of Virginia's House of Burgess (Assembly) for exactly nine days as the May session was drawing to a close. -

Blacklivesmatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding

ISSN: 1941-0832 #BlackLivesMatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding by-Reena N. Goldthree and Aimee Bahng BLACK LIVES MATTER - FERGUSON SOLIDARITY WASHINGTON ETHICAL SOCIETY, 2014 (IMAGE: JOHNNY SILVERCLOUD) RADICAL TEACHER 20 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 106 (Fall 2016) DOI 10.5195/rt.2016.338 college has the lowest percentage of faculty of color. 9 The classroom remains the most radical space Furthermore, Dartmouth has ―earned a reputation as one of possibility in the academy. (bell hooks, of the more conservative institutions in the nation when it Teaching to Transgress) comes to race,‖ due to several dramatic and highly- publicized acts of intolerance targeting students and faculty n November 2015, student activists at Dartmouth of color since the 1980s.10 College garnered national media attention following a I Black Lives Matter demonstration in the campus‘s main The emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement— library. Initially organized in response to the vandalism of a following the killings of Trayvon Martin in 2013 and of Eric campus exhibit on police brutality, the events at Garner and Michael Brown in 2014—provided a language Dartmouth were also part of the national #CollegeBlackout for progressive students and their allies at Dartmouth to mobilizations in solidarity with student activists at the link campus activism to national struggles against state University of Missouri and Yale University. On Thursday, violence, white supremacy, capitalism, and homophobia. November 12th, the Afro-American Society and the The #BlackLivesMatter course at Dartmouth emerged as campus chapter of the National Association for the educators across the country experimented with new ways Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) urged students to to learn from and teach with a rapidly unfolding, multi- wear black to show support for Black Lives Matter and sited movement. -

Our Commitment to Black Lives

Our Commitment to Black Lives June 3, 2020 Dear Friends of the CCE, We are writing today to affirm that we, the staff of the Center for Community Engagement, believe and know that Black Lives Matter. We honor wide-spread grief for the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery among the many named and unnamed Black lives lost to racial violence and hatred in the United States. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement — co-founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi — arose to address ongoing legacies of racialized violence in our country. As BLM leaders have consistently stated, disproportionate violence toward Black communities by law enforcement is one manifestation of anti-Black systemic racism perpetuated across public and private institutions including health care, housing and education. We are firmly and deeply committed to the lives of Black community members, Black youth and their families, and Seattle U’s Black students, faculty and staff. We believe that messages like this one can have an impact, and yet our words ring hollow without action. The Center for Community Engagement is committed to becoming an anti-racist organization. Fulfilling our mission of connecting campus and community requires long-term individual, organizational, and system-wide focus on understanding and undoing white supremacy. We see our commitment to anti-racism as directly linked to Seattle University’s pursuit of a more just and humane world as well as our Jesuit Catholic ethos of cura personalis, care for the whole person. We urge you to participate in ways that speak to you during the national racial crisis that is continuing to unfold.