History of Nffpfw English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![International Current Affairs [April 2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1057/international-current-affairs-april-2010-281057.webp)

International Current Affairs [April 2010]

International Current Affairs [April 2010] • Belgium became the Europe? s first country to ban burqa. • Pakistan?? s National assembly passed a bill that takes away the President s power to dissolve parliament, dismiss a elected government and appoint the three services Chiefs. Pakistan? s parliament passes 18th amendment which was later signed by Presient cutting President? s powers. • USA and Russia signed Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty(START) that allowed a maximum of 1550 deployed overheads, about 30% lower than a limit set in 2002. The treaty was signed in the Progue Castle. • Emergency was imposed in Thailand. • Nuclear Security Summit held at Washington.It was a 47 nation summit wherein P.M. announced setting up of a global nuclear energy centre for conducting research & development of design systems that are secure, proliferation resistant & sustainable. • PM visit USA & Brazil, a two nation tour. He attended Nuclear Security Summit in USA & India- Brazil-S.Africa(IBSA) and Brazil-Russia-India-China(BRIC) summit in Brasilia (Brazil). • 16th SAARC Summit held in Bhutan in 28-29 April. The summit was held in Bhutan for the first time. It is the silver jubilee summit as SAARC has completed 25 years. The summit central theme was ??Climate Change . The summit recommended to declare 2010-2020 as the ??Decade of Intra-regional Connectivity in SAARC . The 17th SAARC summit will be held in Maldives in 2011. International Current Affairs [March 2010] • China will launch in 2011 unmammed space mode ?? Tiangong I for its future space laboratory. • US internet giant Google close its business in China. • India?? s largest telecom service provider Bharti Airtel buy Zain s Africa operations for an enterprise value of $ 10.7 billion (Rs 49000 crore). -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

Adi-Dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi Existence In

Adi-dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi existence in relation to the environmental identity and environmental heritage of Adivasi-Moolvasi communities of Jharkhand. Sudeshna Dutta1 Abstract: Why do the Adivasis of Jharkhand resent the word Development? Since the Koel-Karo movement (Which went on for about thirty-five years) the Adivasis demanded ideal rehabilitation for them. The government officials or policymakers have so far failed to understand the meaning of the ‘ideal rehabilitation.’ In this paper, I argue that without considering the environmental identity of the Adivasi communities, it is impossible to understand the Adivasi interpretation of rehabilitation and the rationals behind such understanding. Adivasi environmental identity, I argue, has a close connection with the land, water, forest. Adivasi culture is closely related to the three elements of nature. Adivasi way of living or Adivasi way of viewing life is practice-oriented and cannot sustain without them. In this paper, I have tried to engage with the three main festivals of Jharkhand to show how the festivals carry the ethos of adi-dharam. The philosophy of Adi-dharam is about maintaining harmonious relationships with the other elements of the ecology. The rationale behind maintaining such relationship is acknowledging the contribution of others in keeping the food-security and food-sovereignty of the community. The structure of the relationships shapes the environmental identity of the Adivasi existence. The rehabilitation programmes, I conclude, need to incorporate the Adivasi interpretation of existence to protect the interest of the Adivasis. Keywords: Environmental Identity, Environmental Heritage, Adi-dharam 1 Sudeshna Dutta is a PhD fellow in the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University. -

A Report of the Workshop on Linguistic Minorities

A REPORT OF THE WORKSHOP ON LINGUISTIC MINORITIES Prof. Rajesh Sachdeva The workshop on Linguistic Minorities was organized by the Government of India, National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs in collaboration with Central Institute of Indian Languages, Ministry of Human Resource Development at Mysore on the 27 th and 28 th March 2006. While the members of the commission and its team were present on the first day, several invited speakers and members of the CIIL faculty also met on the 28 th to dwell further on the issues that had surfaced on the 27 th and also provide an opportunity to others to table their own viewpoints and experience. This report is not an attempt to resurrect the entire event with its varied discourses, although some record is maintained of chronology of speakers. It focuses more on comments /observations made in response to the terms of reference of the commission and only partly on some of the other views expressed. It also places for consideration some recommendations related to the possible follow up. 82 people participated in the event (See Appendix – 1 for the list of participants and programme) TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE COMMISSION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE WORKSHOP The terms of reference of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities were : (a) To suggest criteria for identification of socially and economically backward sections among religious and linguistic minorities. (b) To recommend measures for welfare of socially and economically backward sections among religious and linguistic minorities, including reservation in education and government employment. -

Report on Women and Water

SUMMARY Water has become the most commercial product of the 21st century. This may sound bizarre, but true. In fact, what water is to the 21st century, oil was to the 20th century. The stress on the multiple water resources is a result of a multitude of factors. On the one hand, the rapidly rising population and changing lifestyles have increased the need for fresh water. On the other hand, intense competitions among users-agriculture, industry and domestic sector is pushing the ground water table deeper. To get a bucket of drinking water is a struggle for most women in the country. The virtually dry and dead water resources have lead to acute water scarcity, affecting the socio- economic condition of the society. The drought conditions have pushed villagers to move to cities in search of jobs. Whereas women and girls are trudging still further. This time lost in fetching water can very well translate into financial gains, leading to a better life for the family. If opportunity costs were taken into account, it would be clear that in most rural areas, households are paying far more for water supply than the often-normal rates charged in urban areas. Also if this cost of fetching water which is almost equivalent to 150 million women day each year, is covered into a loss for the national exchequer it translates into a whopping 10 billion rupees per year The government has accorded the highest priority to rural drinking water for ensuring universal access as a part of policy framework to achieve the goal of reaching the unreached. -

Ias Current List-28-08-2019

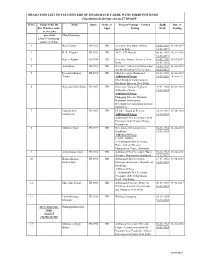

GRADATION LIST OF IAS OFFICERS OF JHARKHAND CADRE WITH THEIR POSTINGS (Gradewise/Scalewise) As on 27-08-2019 Sl.No. Grade/Scale (In Name Batch Mode of Present Postings / Notified DOB Date of Rs.) Whether cadre Appt. Posting DOR Joining or ex-cadre Apex Scale Chief Secretary Level-17 in the pay matric 2.25 Lac 1 Rajiv Gauba JH-1982 RR Secretary, M/o Home Affairs, 15-08-1959 31-08-2017 Govt. of India 31-08-2019 2 B. K. Tripathi JH-1983 RR D.G., ATI, Ranchi. 08-08-1959 26-12-2018 31-08-2019 3 Rajeev Kumar JH-1984 RR Secretary, Finance Services, New 19-02-1960 01-09-2017 Delhi 28-02-2020 4 Amit Khare JH-1985 RR Secretary, Ministry of Information 14-09-1961 01-06-2018 and Broadcasting, Govt. of India 30-09-2021 5 Devendra Kumar JH-1986 RR Chief Secretary, Jharkhand 26-03-1960 31-03-2019 Tiwari Additional Charge 31-03-2020 के अपराहन से Chief Resident Commissioner, Jharkhand Bhawan, New Delhi 6 Nagendra Nath Sinha JH-1987 RR Chairman, National Highway 29-07-1964 05-03-2019 Authority of India 31-07-2024 Additional Charge Managing Director, National Highways Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) 7 Indu Shekhar JH-1987 RR Member, Board of Revenue 24-10-1962 07-06-2018 Chaturvedi Additional Charge 31-10-2022 Additional Chief Secretary, Forest, Environment & Climate Change Department 8 Sukhdeo Singh JH-1987 RR Development Commissioner, 05-03-1964 01-04-2019 Jharkhand 31-03-2024 Additional Charge 1) M.D., GRDA 2) Additional Chief Secretary, Home, Jail and Disaster Management Deptt., Jharkhand 9 Arun Kumar Singh JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, Water 07-12-1963 07-06-2018 Resource Department, Jharkhand 31.12.2023 10 Kailash Kumar JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, 27-07-1962 05-04-2019 Khandelwal Planning-cum-Finance Department, 31-07-2022 Jharkhand Additional Charge 1) Additional Chief Secretary, Personnel, A.R. -

General Elections, 1991 to the Tenth Lok Sabha

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1991 TO THE TENTH LOK SABHA VOLUME I (NATIONAL AND STATE ABSTRACTS & DETAILED RESULTS) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE92-LS (VOL. I) © Election Commision of India, 1992 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 1992 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics and Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1991 (10th LOK SABHA) STATISTICAL REPORT – VOLUME I (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 4 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 5 3. Size of Electorate 6 4. Voter Turnout and Polling Station 7 5. Number of Candidates per Constituency 8 - 9 6. Number of Candidates and Forfeiture of Deposits 10 7. Electors Data Summary 11 - 41 8. List of Successful Candidates 42 - 54 9. Performance of National Parties Vis-à-vis Others 55 10. Seats won by Parties in States / UT’s 56 - 59 11. Seats won in States / UT’s by Parties 60 - 63 12. Votes Polled by Parties – National Summary 64 - 71 13. Votes Polled by Parties in States / UT’s 72 - 90 14. Votes Polled in States / UT by Parties 91 - 104 15. Women’s Participation in Polls 105 16. Performance of Women Candidates 106 17. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

AR-Cover 2019--FINAL FOR PRINTING-CONVERT TO OUTLINE.ai 1 02-05-2019 11:37:19 AR-Cover 2019--FINAL FOR PRINTING-CONVERT TO OUTLINE.ai 2 02-05-2019 11:37:26 ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Photographs TISS acknowledges the photographers of all the images included in this Annual Report. Photo credits have been given where information was provided. Page 1, 22, 224, 225: Nagaland Centre Page 4: Saksham Page 9 (Top): Information and Public Relations Department, Chatra Page 9 (Bottom): Vimal Chunni Page 10 (Top), 26, 29 (Bottom), 38, 47, 127, 145 & 174: Mangesh Gudekar Page 14 (Top): Department of Communications, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health Page 21: Neeraj Kumar Page 27 (Bottom) & 167: CEIAR Team Page 29 (Top): Deepa Bhalerao Page 34: Jennifer Mujawar Page 42 & 43: Counselling Centre Page 52: Sudha Ganapathi Cover Design: www.freepik.com © Tata Institute of Social Sciences, 2019 2018–2019 ANNUAL REPORT PRODUCTION TEAM Sudha Ganapathi, Vijender Singh and Gauri Galande Printed at India Printing Works, 42, G.D. Ambekar Marg, Wadala, Mumbai 400 031 Contents DIRECTOR’S REPORT A Community Engaged University Called TISS .........................................................................................................................................1 Engagement with State, Society and the Industry ..................................................................................................................................3 Awards, Fellowships and Recognition ...................................................................................................................................................... -

CUJ Advisor • Prof

ACADEMIA FACULTY PROFILE Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi (Established by an Act of Parliament of India, 2009) Kkukr~ fg cqfº dkS'kye~ Knowledge to Wisdom Publishers Central University of Jharkhand Brambe, Ranchi - 835205 Chief Patron • Prof. Nand Kumar Yadav 'Indu' Vice-Chancellor, CUJ Advisor • Prof. S.L. Hari Kumar Registrar, CUJ Editors • Dr. Devdas B. Lata, Associate Professor, Department of Energy Engineering • Dr. Gajendra Prasad Singh, Associate Professor, Department of Nano Science and Technology • Mr. Rajesh Kumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication © Central University of Jharkhand From the Vice Chancellor's Desk... t’s a matter of immense pride that the faculty of our Central University of Jharkhand Iare not only teachers of repute but also excellent researchers. They have received national and international recognition and awards for their widely acclaimed papers and works. Their scholarly pursuit reflect the strength of the University and provide ample opportunities for students to carry out their uphill tasks and shape their career. The endeavour of the faculty members to foster an environment of research, innovation and entrepreneurial mindset in campus gives a fillip to collaborate with other academic and other institutions in India and abroad. They are continuously on a lookout for opportunities to create, enrich and disseminate the knowledge in their chosen fields and convert to the welfare of the whole humanity. Continuous introspection and assessment of teaching research and projects add on devising better future planning and innovations. Training and mentoring of students and scholars helps to create better, knowledgeable and responsible citizens of India. I hope this brochure will provide a mirror of strength of CUJ for insiders and outsiders. -

LIST of PMAY(U), Vertical- IV None Starter Beneficiaries List RANCHI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION RANCHI Sl

LIST OF PMAY(U), Vertical- IV None Starter Beneficiaries list RANCHI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION RANCHI Sl. Ward F.Y. Name of the Beneficiary Father’s/ Husband's name No. No. 1 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Anita Devi Bablu Munda 2 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Anita Toppo Sankar Oraon 3 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Bina Kachhap Balram Kachhap 4 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Futun Devi Manoj Munda 5 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Manish Linda Late Naresh Linda 6 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Manju Toppo Late Birsh Toppo 7 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Munni Gari Ramesh Chandra Gari 8 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Munni Kachhap Muna kachhap 9 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Sarita Devi Raju Munda 10 1 2017-18 (1st Phase) Sumita Devi Depu Munda 11 1 2017-18 (2nd Phase) NAVIN KUMAR GUPTA RAM KUMAR GUPTA 12 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) CHAITA MUNDA LATE ETWA MUNDA 13 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) DAHARI GARI LATE BIRSA GARI 14 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) GUDU ORAON LATE KHORCHE ORAON 15 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) PUNA ORAON MAHADEV ORAON 16 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) RAJU MUNDA BITA MUNDA 17 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) SANDHAYA KACHHAP VISHRAM KACHHAP 18 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) VIJAY MUNDA LATE RAGHUNANDAN PRASHAD 19 1 2017-18 (3rd Phase) VINA MUNDA MANTU MUNDA 20 1 2017-18 (4th Phase) BANDANA TIRKEY ANJAN TIRKEY 21 1 2017-18 (4th Phase) MAHENDRA KACHHAP MAHESH KACHHAP 22 1 2017-18 (4th Phase) PARNI ORAON TUICHA ORAON An evaluation version of novaPDF was used to create this PDF file. -

An Anthropological Study of Rural Jharkhand, India

Understanding the State: An Anthropological Study of Rural Jharkhand, India Alpa Shah London School of Economics and Political Science University of London PhD. in Anthropology 2003 UMI Number: U615999 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615999 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ?O ltT tC A L AND uj. TR£££ S F ZZit, Abstract This thesis explores understandings of the state in rural Jharkhand, Eastern India. It asks how and why certain groups exert their influence within the modem state in India, and why others do not. To do so the thesis addresses the interrelated issuesex-zamindar of and ex-tenant relations, development, corruption, democracy, tribal movements, seasonal casual labour migration, extreme left wing militant movements and moral attitudes towards drink and sex. This thesis is informed by twenty-one months of fieldwork in Ranchi District of which, for eighteen months, a village in Bero Block was the research base. The thesis argues that at the local level in Jharkhand there are at least two main groups of people who hold different, though related, understandings of the state. -

Minute to Minute Programme

Three Days’ International Seminar (September 2, 3 & 4, 2016) on Emerging New Identities in Dalit and Tribal Literature and Society Organized by The Department of English and Foreign Languages Faculty of Humanities and Philology Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak (MP) In Collaboration with Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi Day one (September 02, 2016) Date Time Programme Details Resource Persons 02/09/16 10.00am- Inauguration Keynote Speaker: Dr. Manu Baligar 12.15 pm Guest of Honour: Prof Heniz W Venue: Pof. Laxman Wessler Special Guest: Sri Harish Manglam Havanur Auditorium Chief Guest: Dr. Rajshekhar Hatgundi Chairman: Prof. T.V. Kattimani, Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor, IGNTU 12.15pm- TEA BREAK 12.30pm 12.30pm- Plenary Talk - 1 Chairman: Prof H W Wessler 1.30pm Theme: Conceptualizing Rapporteur: Priyanka Mishra Dalit Literature Presenters: Venue: Pof. Laxman Havanur Dr. A Consolaro Auditorium Mr. Harish Mangalam 1.30pm- LUNCH Venue: Samakka Sarakka Mega Mess 2.30pm 2.30 pm– Plenary Talk – 2 3.45 pm Chairman: Prof. Sonjoy Saxena Theme: New Thoughts and Dalit Literature Rapporteur: Sonu Singh Presenters: Prof. M L Jadhav Venue: Pof. Laxman Havanur Auditorium Dr. B. Karankal Dr. Hansya Pandya 3.45.pm - Panel Discussion: Chairman: Mr Laxman Gaikwad 4.45 pm Theme: Dalit and Tribal Rapporteur: Yogesh Shukla Literature or Dalitribal Venue: Pof. Laxman Havanur Literature Auditorium Presenters: Dr. Jai Prakash Kardam Mr Vaharu Sonewane Prof Heniz Werner Wessler 3.45pm- TEA BREAK Venue: Near to Pof. Laxman Havanur 5.00 pm Auditorium Parallel Technical Session – 1 Venue: Prof Ramdayal Munda Library Basement 2/09/20 5.00pm- Theme: Dalit Literature: Chairman: Dr.