8.4 White Dwarfs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

Temperature, Mass and Size of Stars

Title Astro100 Lecture 13, March 25 Temperature, Mass and Size of Stars http://www.astro.umass.edu/~myun/teaching/a100/longlecture13.html Also, http://www.astro.columbia.edu/~archung/labs/spring2002/spring2002.html (Lab 1, 2, 3) Goal Goal: To learn how to measure various properties of stars 9 What properties of stars can astronomers learn from stellar spectra? Î Chemical composition, surface temperature 9 How useful are binary stars for astronomers? Î Mass 9 What is Stefan-Boltzmann Law? Î Luminosity, size, temperature 9 What is the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram? Î Distance and Age Temp1 Stellar Spectra Spectrum: light separated and spread out by wavelength using a prism or a grating BUT! Stellar spectra are not continuous… Temp2 Stellar Spectra Photons from inside of higher temperature get absorbed by the cool stellar atmosphere, resulting in “absorption lines” At which wavelengths we see these lines depends on the chemical composition and physical state of the gas Temp3 Stellar Spectra Using the most prominent absorption line (hydrogen), Temp4 Stellar Spectra Measuring the intensities at different wavelength, Intensity Wavelength Wien’s Law: λpeak= 2900/T(K) µm The hotter the blackbody the more energy emitted per unit area at all wavelengths. The peak emission from the blackbody moves to shorter wavelengths as the T increases (Wien's law). Temp5 Stellar Spectra Re-ordering the stellar spectra with the temperature Temp-summary Stellar Spectra From stellar spectra… Surface temperature (Wien’s Law), also chemical composition in the stellar -

Mass-Radius Relations for Massive White Dwarf Stars

A&A 441, 689–694 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20052996 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics Mass-radius relations for massive white dwarf stars L. G. Althaus1,, E. García-Berro1,2, J. Isern2,3, and A. H. Córsico4,5, 1 Departament de Física Aplicada, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Av. del Canal Olímpic, s/n, 08860 Castelldefels, Spain e-mail: [leandro;garcia]@fa.upc.es 2 Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya, Ed. Nexus, c/Gran Capità 2, 08034 Barcelona, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 3 Institut de Ciències de l’Espai, C.S.I.C., Campus UAB, Facultat de Ciències, Torre C-5, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain 4 Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, (1900) La Plata, Argentina e-mail: [email protected] 5 Instituto de Astrofísica La Plata, IALP, CONICET, Argentina Received 4 March 2005 / Accepted 18 July 2005 Abstract. We present detailed theoretical mass-radius relations for massive white dwarf stars with oxygen-neon cores. This work is motivated by recent observational evidence about the existence of white dwarf stars with very high surface gravities. Our results are based on evolutionary calculations that take into account the chemical composition expected from the evolu- tionary history of massive white dwarf progenitors. We present theoretical mass-radius relations for stellar mass values ranging from1.06to1.30 M with a step of 0.02 M and effective temperatures from 150 000 K to ≈5000 K. A novel aspect predicted by our calculations is that the mass-radius relation for the most massive white dwarfs exhibits a marked dependence on the neutrino luminosity. -

Download the AAS 2011 Annual Report

2011 ANNUAL REPORT AMERICAN ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY aas mission and vision statement The mission of the American Astronomical Society is to enhance and share humanity’s scientific understanding of the universe. 1. The Society, through its publications, disseminates and archives the results of astronomical research. The Society also communicates and explains our understanding of the universe to the public. 2. The Society facilitates and strengthens the interactions among members through professional meetings and other means. The Society supports member divisions representing specialized research and astronomical interests. 3. The Society represents the goals of its community of members to the nation and the world. The Society also works with other scientific and educational societies to promote the advancement of science. 4. The Society, through its members, trains, mentors and supports the next generation of astronomers. The Society supports and promotes increased participation of historically underrepresented groups in astronomy. A 5. The Society assists its members to develop their skills in the fields of education and public outreach at all levels. The Society promotes broad interest in astronomy, which enhances science literacy and leads many to careers in science and engineering. Adopted 7 June 2009 A S 2011 ANNUAL REPORT - CONTENTS 4 president’s message 5 executive officer’s message 6 financial report 8 press & media 9 education & outreach 10 membership 12 charitable donors 14 AAS/division meetings 15 divisions, committees & workingA groups 16 publishing 17 public policy A18 prize winners 19 member deaths 19 society highlights Established in 1899, the American Astronomical Society (AAS) is the major organization of professional astronomers in North America. -

The Connection Between Galaxy Stellar Masses and Dark Matter

The Connection Between Galaxy Stellar Masses and Dark Matter Halo Masses: Constraints from Semi-Analytic Modeling and Correlation Functions by Catherine E. White A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland August, 2016 c Catherine E. White 2016 ⃝ All rights reserved Abstract One of the basic observations that galaxy formation models try to reproduce is the buildup of stellar mass in dark matter halos, generally characterized by the stellar mass-halo mass relation, M? (Mhalo). Models have difficulty matching the < 11 observed M? (Mhalo): modeled low mass galaxies (Mhalo 10 M ) form their stars ∼ ⊙ significantly earlier than observations suggest. Our goal in this thesis is twofold: first, work with a well-tested semi-analytic model of galaxy formation to explore the physics needed to match existing measurements of the M? (Mhalo) relation for low mass galaxies and second, use correlation functions to place additional constraints on M? (Mhalo). For the first project, we introduce idealized physical prescriptions into the semi-analytic model to test the effects of (1) more efficient supernova feedback with a higher mass-loading factor for low mass galaxies at higher redshifts, (2) less efficient star formation with longer star formation timescales at higher redshift, or (3) less efficient gas accretion with longer infall timescales for lower mass galaxies. In addition to M? (Mhalo), we examine cold gas fractions, star formation rates, and metallicities to characterize the secondary effects of these prescriptions. ii ABSTRACT The technique of abundance matching has been widely used to estimate M? (Mhalo) at high redshift, and in principle, clustering measurements provide a powerful inde- pendent means to derive this relation. -

Calibration Against Spectral Types and VK Color Subm

Draft version July 19, 2021 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX63 Direct Measurements of Giant Star Effective Temperatures and Linear Radii: Calibration Against Spectral Types and V-K Color Gerard T. van Belle,1 Kaspar von Braun,1 David R. Ciardi,2 Genady Pilyavsky,3 Ryan S. Buckingham,1 Andrew F. Boden,4 Catherine A. Clark,1, 5 Zachary Hartman,1, 6 Gerald van Belle,7 William Bucknew,1 and Gary Cole8, ∗ 1Lowell Observatory 1400 West Mars Hill Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA 2California Institute of Technology, NASA Exoplanet Science Institute Mail Code 100-22 1200 East California Blvd. Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Systems & Technology Research 600 West Cummings Park Woburn, MA 01801, USA 4California Institute of Technology Mail Code 11-17 1200 East California Blvd. Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5Northern Arizona University Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science NAU Box 6010 Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA 6Georgia State University Department of Physics and Astronomy P.O. Box 5060 Atlanta, GA 30302, USA 7University of Washington Department of Biostatistics Box 357232 Seattle, WA 98195-7232, USA 8Starphysics Observatory 14280 W. Windriver Lane Reno, NV 89511, USA (Received April 18, 2021; Revised June 23, 2021; Accepted July 15, 2021) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT We calculate directly determined values for effective temperature (TEFF) and radius (R) for 191 giant stars based upon high resolution angular size measurements from optical interferometry at the Palomar Testbed Interferometer. Narrow- to wide-band photometry data for the giants are used to establish bolometric fluxes and luminosities through spectral energy distribution fitting, which allow for homogeneously establishing an assessment of spectral type and dereddened V0 − K0 color; these two parameters are used as calibration indices for establishing trends in TEFF and R. -

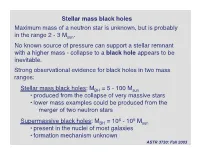

Stellar Mass Black Holes Maximum Mass of a Neutron Star Is Unknown, but Is Probably in the Range 2 - 3 Msun

Stellar mass black holes Maximum mass of a neutron star is unknown, but is probably in the range 2 - 3 Msun. No known source of pressure can support a stellar remnant with a higher mass - collapse to a black hole appears to be inevitable. Strong observational evidence for black holes in two mass ranges: Stellar mass black holes: MBH = 5 - 100 Msun • produced from the collapse of very massive stars • lower mass examples could be produced from the merger of two neutron stars 6 9 Supermassive black holes: MBH = 10 - 10 Msun • present in the nuclei of most galaxies • formation mechanism unknown ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Other types of black hole could exist too: 3 Intermediate mass black holes: MBH ~ 10 Msun • evidence for the existence of these from very luminous X-ray sources in external galaxies (L >> LEdd for a stellar mass black hole). • `more likely than not’ to exist, but still debatable Primordial black holes • formed in the early Universe • not ruled out, but there is no observational evidence and best guess is that conditions in the early Universe did not favor formation. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Basic properties of black holes Black holes are solutions to Einstein’s equations of General Relativity. Numerous theorems have been proved about them, including, most importantly: The `No-hair’ theorem A stationary black hole is uniquely characterized by its: • Mass M Conserved • Angular momentum J quantities • Charge Q Remarkable result: Black holes completely `forget’ how they were made - from stellar collapse, merger of two existing black holes etc etc… Only applies at late times. -

Stellar Evolution

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 19 www.accessscience.com Stellar evolution Contributed by: James B. Kaler Publication year: 2014 The large-scale, systematic, and irreversible changes over time of the structure and composition of a star. Types of stars Dozens of different types of stars populate the Milky Way Galaxy. The most common are main-sequence dwarfs like the Sun that fuse hydrogen into helium within their cores (the core of the Sun occupies about half its mass). Dwarfs run the full gamut of stellar masses, from perhaps as much as 200 solar masses (200 M,⊙) down to the minimum of 0.075 solar mass (beneath which the full proton-proton chain does not operate). They occupy the spectral sequence from class O (maximum effective temperature nearly 50,000 K or 90,000◦F, maximum luminosity 5 × 10,6 solar), through classes B, A, F, G, K, and M, to the new class L (2400 K or 3860◦F and under, typical luminosity below 10,−4 solar). Within the main sequence, they break into two broad groups, those under 1.3 solar masses (class F5), whose luminosities derive from the proton-proton chain, and higher-mass stars that are supported principally by the carbon cycle. Below the end of the main sequence (masses less than 0.075 M,⊙) lie the brown dwarfs that occupy half of class L and all of class T (the latter under 1400 K or 2060◦F). These shine both from gravitational energy and from fusion of their natural deuterium. Their low-mass limit is unknown. -

Stellar Mass and Age Determinations �,�� I

A&A 541, A41 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117749 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Stellar mass and age determinations , I. Grids of stellar models from Z = 0.006 to 0.04 and M =0.5to3.5M N. Mowlavi1,2, P. Eggenberger1 ,G.Meynet1,S.Ekström1,C.Georgy3, A. Maeder1, C. Charbonnel1, and L. Eyer1 1 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 ISDC, Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, chemin d’Écogia, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland 3 Centre de Recherche Astrophysique, École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, 46 allée d’Italie, 69384 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 21 July 2011 / Accepted 1 December 2011 ABSTRACT Aims. We present dense grids of stellar models suitable for comparison with observable quantities measured with great precision, such as those derived from binary systems or planet-hosting stars. Methods. We computed new Geneva models without rotation at metallicities Z = 0.006, 0.01, 0.014, 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04 (i.e. [Fe/H] from −0.33 to +0.54) and with mass in small steps from 0.5 to 3.5 M. Great care was taken in the procedure for interpolating between tracks in order to compute isochrones. Results. Several properties of our grids are presented as a function of stellar mass and metallicity. Those include surface properties in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, internal properties including mean stellar density, sizes of the convective cores, and global asteroseismic properties. Conclusions. We checked our interpolation procedure and compared interpolated tracks with computed tracks. -

Stellar Mass Black Holes

Stellar mass black holes Black Hole Physics, 2018 4 5 Distinctive features that can indicate the presence of a black hole Observe two or more of these features to “find” a black hole: Gravitational deflection of light, by an amount requiring black hole masses and sizes. X-ray and/or g-ray emission from ionized gas falling into the black hole. Orbital motion of nearby stars or gas clouds that can be used to infer the mass of (perhaps invisible) companions: a mass too large to be a white dwarf or a neutron star might correspond to a black hole. Motion close to the speed of light, or apparently greater than the speed of light (“superluminal motion”). Extremely large luminosity that cannot be explained easily by normal stellar energy generation. Direct observation of a large, massive accretion disk. 9 Stellar-mass black holes By this we mean black holes formed by the gravitational collapse of dead stars that are too massive to become neutron stars or white dwarfs. Best clues: High-energy light (X/g rays): gives promising, but not completely unambiguous, detections of black holes. Orbital motion of companion stars • Orbit size, speed plus Newton’s laws can be used to work out the mass of a visibly-dim (but perhaps X-ray bright) companion. If it’s more than 2 M … • We can’t usually resolve the details of the orbit directly in images, but we can measure orbital speeds and periods well enough to work out what the orbit is, using the Doppler effect. 10 High-energy light from stellar-mass black holes X-ray or g-ray emission. -

Astronomy General Information

ASTRONOMY GENERAL INFORMATION HERTZSPRUNG-RUSSELL (H-R) DIAGRAMS -A scatter graph of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitude or luminosities versus their spectral types or classifications and effective temperatures. -Can be used to measure distance to a star cluster by comparing apparent magnitude of stars with abs. magnitudes of stars with known distances (AKA model stars). Observed group plotted and then overlapped via shift in vertical direction. Difference in magnitude bridge equals distance modulus. Known as Spectroscopic Parallax. SPECTRA HARVARD SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (1-D) -Groups stars by surface atmospheric temp. Used in H-R diag. vs. Luminosity/Abs. Mag. Class* Color Descr. Actual Color Mass (M☉) Radius(R☉) Lumin.(L☉) O Blue Blue B Blue-white Deep B-W 2.1-16 1.8-6.6 25-30,000 A White Blue-white 1.4-2.1 1.4-1.8 5-25 F Yellow-white White 1.04-1.4 1.15-1.4 1.5-5 G Yellow Yellowish-W 0.8-1.04 0.96-1.15 0.6-1.5 K Orange Pale Y-O 0.45-0.8 0.7-0.96 0.08-0.6 M Red Lt. Orange-Red 0.08-0.45 *Very weak stars of classes L, T, and Y are not included. -Classes are further divided by Arabic numerals (0-9), and then even further by half subtypes. The lower the number, the hotter (e.g. A0 is hotter than an A7 star) YERKES/MK SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (2-D!) -Groups stars based on both temperature and luminosity based on spectral lines.