Forced to the Fringes: Disasters of 'Resettlement' in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

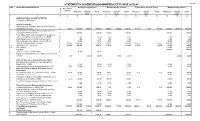

Statement V : Scheme Wise Budget

STATEMENT:V SCHEME/PROGRAMME/PROJECTS WISE OUTLAY ₹ in Lakh S.No. Sector/Department/Scheme Budget Outlay 2019-20 Revised Outlay 2019-20 Expenditure 2019-20 (Prov.) Budget Outlay 2020-21 R Expenditure C 2018-19 Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total L Loan Loan Loan Loan 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 AGRICULTURE & ALLIED ACTIVITIES A Development Department I Animal Husbandry 1 Improvement of Veterinary Services and Control of Contagious Diseases C 170.65 800.00 700.00 1500.00 800.00 700.00 1500.00 519.94 28.99 548.93 1300.00 3000.00 4300.00 2 Improvement of Veterinary Services and Control of Contagious Diseases-SCSP R 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 3 Farm Advisiory Integrated agricultural development scheme including extn. , education etc. -SCSP R 5.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 4.00 4.00 4 Soil testing & Soil reclamation & saline-SCSP R 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 5 GIA to animal welfare advisory board of Delhi R 10.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 80.00 80.00 6 GIA for Shifting of Dairy Colonies R 1060.82 1200.00 1200.00 1200.00 1200.00 1167.34 1167.34 1200.00 1200.00 7.a GIA to S.P.C.A. (General) R 289.00 400.00 400.00 210.00 210.00 210.00 210.00 80.00 80.00 7.b GIA (Salary) R 220.00 220.00 Sub total 300.00 300.00 8 Input sale Centres at BDO Offices R 30.00 30.00 9 Expansion & Reorganisation of fishery activities in UT of Delhi C 4.63 20.00 20.00 17.00 17.00 20.00 20.00 2 National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture a. -

Rajam Krishnan and Indian Feminist Hermeneutics

Rajam Krishnan and Indian Feminist Hermeneutics Rajam Krishnan and Indian Feminist Hermeneutics Translated and Edited by Sarada Thallam Rajam Krishnan and Indian Feminist Hermeneutics Translated and Edited by Sarada Thallam This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Sarada Thallam All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2995-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2995-3 Rajam Krishnan (1925-2014) TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................... ix Rajam Krishnan A Voice Registered ..................................................................................... xi C S Lakshmi Rajam Krishnan and the Indian Feminist Hermeneutical Tradition ........ xvii Acknowledgments ..................................................................................... xli Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Primordial Mother Chapter Two ................................................................................................ 5 The Cult of Hospitality Chapter -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Final ELIGIBILITY Male 11-12

DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (ESTT.-II BRANCH) FINAL ELIGIBILITY LIST FOR PROMOTION TO THE POST OF LECTURER (AGRICULTURE) MALE 2011-12 S.No. Employee Employee Name Date of Birth School ID School Name Present Post SENIORITY BLOCK Date of Date of REMARKS ID NO. YEAR appointment acquiring to the post of Qualification TGT for the post of Lecturer UR NO CANDIDATE SC 1 20051829 RAJENDRA PRASAD 01-May-64 1106119 GBSSS A-BLK, NAND TGT S.ST. 9672 2003-09 31-Oct-92 1988 NAGRI ST NO CANDIDATE Page 1 of 249 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (ESTT.-II BRANCH) FINAL ELIGIBILITY LIST FOR PROMOTION TO THE POST OF LECTURER (BIOLOGY) MALE 2011-12 S.No. Employee Employee Name Date of Birth School ID School Name Present Post SENIORITY BLOCK Date of Date of REMARKS ID NO. YEAR appointment acquiring to the post of Qualification TGT for the post of Lecturer UR 1 19831638 DHIRENDRA RAJ 01-Jan-55 1002007 East Vinod Nagar-SBV (Jai TGT N.SC. 929 1981-85 3-Nov-1983 16-Sep-78 Prakash Narayan) 2 19910899 BIKRAM SINGH 30-Apr-62 1106002 Dilshad Garden, Block C- TGT N.SC. 3850 1986-92 1-Oct-1991 30-Jun-84 SBV 3 19911129 DHYAN SINGH 25-Mar-67 2128008 Rani Jhansi Road-SBV TGT N.SC. 3854 1986-92 28-Oct-1991 4-Aug-89 ECONOMICS BHATI ALSO 4 19911176 PRABHAKAR 24-Feb-56 1104020 Gokalpuri-SKV TGT N.SC. 3855 1986-92 19-Nov-1991 31-Dec-81 CHANDRA AWASTHI 5 19910662 VINAY KUMAR 09-Nov-63 1002004 Shakarpur, No.2-SBV TGT N.SC. -

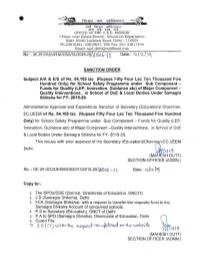

(03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/4506---1 L Date:- V21,1 E

• f-. T4"-1T q-zI t"-- TaTT 365-1-Z:175-1" Li al ara OFFICE OF THE U.E.E. MISSION I Floor, near Estate Branch, Education Department Distt. North Lucknow Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph.23810361, 23810647, Tele Fax:-011 23811442 Email:[email protected] No: - DE.29 (03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/4506---1 L Date:- V21,1 e\ SANCTION ORDER Subject: A/A & EIS of Rs. 54.105 lac (Rupees Fifty Four Lac Ten Thousand Five Hundred Only) for School Safety Programme under Sub Component - Funds for Quality (LEP, Innovation, Guidance etc) of Major Component - Quality Interventions, in School of DoE & Local Bodies Under Samagra Shiksha for FY- 2019-20. Administrative Approval and Expenditure Sanction of Secretary (Education)/ Chairman- EC,UEEM of Rs. 54.105 lac (Rupees Fifty Four Lac Ten Thousand Five Hundred Only) for School Safety Programme under Sub Component - Funds for Quality (LEP, Innovation, Guidance etc) of Major Component -Quality Interventions, in School of DoE & Local Bodies Under Samagra Shiksha for FY- 2019-20. This issues with prior approval of the Secretary (Education)/Chairm n-EC,UEEM Delhi. 11 0 (MA ESH DUTT) SECTION OFFICER (ADMN.) No: - DE.29 (03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/6604 Date:- )211)_111 Copy to:- 1. The DPOs/DDE (District), Directorate of Education, GNCTD 2. J.D (Samagra Shiksha), Delhi. 3. FCA (Samagra Shiksha), with a request to transfer the requisite fund to the Samagra Shiksha Account of concerned schools. 4. P.S to Secretary (Education), GNCT of Delhi. 5. P.A to SPD (Samagra Shiksha), Directorate of Education, Delhi. -

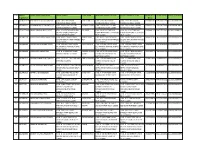

S.NO Vehicle Owner Name & Mobile No

S.NO Vehicle Owner Name & Mobile No. Owner Address Driver Name Permanent Address of Driver Current Address of Driver Phone No. of Driver adhaar Driving License No. Registration Driver 1 DL1NCR1329No. RAKESH MEHTO & 8510802182 H NO. 744 SEWA SADAN RAKESH MEHTO H NO. 744 SEWA SADAN H NO. 744 SEWA SADAN 8510802182 859303661294 DL1320100045444 MANDAWAL DELHI 110092 MANDAWAL DELHI 110092 MANDAWAL DELHI 110092 2 DL1RW0455 RAVINDER SINGH & 8368722771 H NO. 230/21D RLY COLONY RAVINDER SINGH H NO. 230/21D RLY COLONY H NO. 230/21D RLY COLONY 8368722771 526508337681 DL0420000176836 MANDAWALI DELHI 110092 MANDAWALI DELHI 110092 MANDAWALI DELHI 110092 3 UP16DT7335 MOHD YAMIN & 8527116757 H NO.12 25 FUTA ROAD BUDH MD JAKIR H NO. US-129 UTTARI SCH H NO. US-129 UTTARI SCH 9015888127 756715197621 DL1320110086945 VIHAR SECTOR 63 NOIDA GB BLOCK MANDAWALI FAZALPUR BLOCK MANDAWALI FAZALPUR NAGAR UTTAR PRADESH DELHI 110092 DELHI 110092 4 DL1RN2218 RAM BHAROS ROY & 9968751281 H NO. B-661 GHAROLI DAIRY RAM BHAROS H NO. B-661 GHAROLI DAIRY H NO. B-661 GHAROLI DAIRY 9968751281 585566582625 DL0720020037165 COLONY MAYUR VIHAR PHASE-3 ROY COLONY MAYUR VIHAR PHASE-3 COLONY MAYUR VIHAR PHASE-3 DELHI 110096 DELHI 110096 DELHI 110096 5 DL1RN4468 AMOD KUMAR & 9999704182 H NO. 35D/488 STREET NO33 AMOD KUMAR H NO. 35D/488 STREET NO33 H NO. 35D/488 STREET NO33 9999704182 536785468862 DL0319990023759 MOLAR BAND EXTENTION NEW MOLAR BAND EXTENTION NEW MOLAR BAND EXTENTION NEW DELHI 110044 DELHI 110044 DELHI 110044 6 DL1RW5655 NIRANJAN & 9654497393 H NO. A-18 CHANDAR VIHAR RAMESH KUMAR H NO. 35/15 C BHIKAM SINGH H NO. -

Womanhood and Spirituality: a Journey Between Transcendence and Tradition

Womanhood and Spirituality: A Journey between Transcendence and Tradition USHA S. NAYAR This article focuses on how women in the past and women in contemporary India have chosen the path of spirituality, and how Indian culture has positioned women vis-a-vis spirituality. It explores female spirituality in a patriarchal para digm through women like Sita, Meera, Savitri and Kannagi, who faced humilia tion and hostility, but who tread the path of single-minded devotion to their principles and thus combined the feminine principle of grace with tenacity, stead fastness of purpose, vision and character. These prototypes inspire and guide the women in India even today and the article illustrates this through contemporary profiles in courage. The article stresses on the fact that in the Hindu pantheon of gods and goddesses, every god has a goddess, and as the form of Ardhanaareeshwara, the fusion of Shiva and Shakti in one body, denotes, male and female principles work together as equal partners in the universe. Other in stances reiterate that in ancient India, women occupied a very important position. While analysing the spirituality of women as a cultural expression, the study un derlines the fact that the Hindu version of the Mother image has manifested itself in the vision of Bharat Mata and underlines the fact that spirituality mediates rela tionships. It heals, provides succour to the emotionally needy, physically abused, and rebuilds fundamental trust in oneself. The modern approach to spirituality, according to this study, defines it as a means of reaching equilibrium or harmony through gender equality. Prof. Usha S. -

Ground Water Year Book National Capital Territory, Delhi 2018-19

Ground Water Year Book National Capital Territory, Delhi 2018-19 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD STATE UNIT OFFICE, DELHI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI October - 2020 II FOREWORD Ground Water Year Book is based on the information generated through field studies. The data has been analyzed by Officers of Central Ground Water Board, State Unit Office, Delhi and presented in the report. The reports, annexure and maps have been generated using GEMS Software, Version-2.1, developed indigenously by Central Ground Water Board. Depiction of ground water conditions in Delhi provides information on availability of groundwater in terms of quantity and quality, development prospects and management options. I am happy to note that the scientific information in this report is presented in a simplified form. I sincerely hope this report will be of immense help not only to planners, administrators, researchers and policy makers in formulating development and management strategy but also to the common man in need of such information to make himself aware of the ground situation in NCT Delhi. The untiring efforts made by Sh. Faisal Abrar, Assistant Hydrogeologist, Sh. V Praveen Kumar, STA (Hydrogeology) & Sh. S Ashok Kumar, STA (Hydrogeology) for bringing out this report are highly appreciated. (S K Juneja) Officer in charge Central Ground Water Board State Unit Office, Delhi III IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2018-19: NCT DELHI National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi occupies an area of 1483 sq. km. and lies between 28° 24’ 15’’ to 28° 53’ 00’’ N latitudes and 76° 50’ 24” to 77° 20’ 30” E longitudes. -

Educational Development Facilities

DELHI RED FORT, NEW DELHI March 2021 For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Economic Snapshot 9 Physical Infrastructure 15 Social Infrastructure 22 Industrial Infrastructure 25 Key Sectors 28 Key Procedures & Policies 36 Appendix 49 2 Executive summary Strong economic growth . Delhi is one of the fastest growing states of the country. 1 . At current prices, the advance estimate of Gross State Domestic Product of Delhi is Rs 7.98 trillion (US$ 108.33 billion) in 2020-21. Attractive real estate industry . Government focus towards affordable housing is boosting the growth of the real estate sector in the state. 2 . The real estate, ownership of dwelling & professional services contributed ~29.29% to Delhi’s GSVA in 2019-20. Growing tourism industry . Owing to its location, connectivity and rich cultural history, Delhi has always been a prime tourist attraction of the country. 3 . Delhi ranked as the second-best tourist destination in India in 2019. Two new schemes—Delhi Heritage Promotion and Delhi Tourism Circuit—will be introduced to boost tourism. Policy support . The state has set up a single window approval mechanism to facilitate entrepreneurs in obtaining clearance from various departments/agencies for the establishment of industrial enterprises in the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi. 4 . The new Industrial Policy 2010-21 aims to provide a conducive environment for knowledge based and hi-tech IT/ITeS industries in Delhi. Note: GSVA - Gross State Value Added Source: State Budget, Ministry of Tourism, Central Statistics Office, Hotelivate India State Ranking Survey 2017 3 INTRODUCTION 4 Delhi fact file 1,483 sq.km. -

Membership Under Statute 7(1)(I) to (Xiv)

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE ACADEMIC COUNCIL – 2014-15 as on 16.06.2014 SR. MEMBERSHIP UNDER STATUTE RESIDENTIAL PHONE-OFF/RESI NO. 7(1)(I) TO (XIV) ADDRESS (e-mail address) 1. STATUTE 7(1)(i) Prof. Dinesh Singh Vice-Chancellor University of Delhi Delhi-110007 2. STATUTE 7(1)(ii) Prof. Sudhish Pachauri 17-B-1, HT Apts., 27667066 (O) Pro-Vice-Chancellor Mayur Vihar, 22750253 (R) University of Delhi Phase-I, 22759623 (R) Delhi-110007 Delhi-110092 [email protected] 3. STATUTE 7(1)(iii) C-26 9810065218 (M) Prof. Malashri Lal Chirag Enclave, 27667066 (O) Dean of Colleges, New Delhi-110048. 26213595 (R) University of Delhi, [email protected] Delhi-110007. 4. STATUTE 7(1)(iv) Prof. Umesh Rai 38/22 Probyn Road, 24113045 (O) Director University of Delhi, 27666298 (R) University of Delhi South Campus Delhi-110007 9958969578 (M) Benito Juarez Road [email protected] New Delhi-110021 [email protected] 5. STATUTE 7(1)(v) [email protected] Prof. C.S. Dubey C-10, Maurice Nagar 27667041 (O) Director (Officiating) Delhi-110007 27662776 (O) Campus of Open Learning, 9811074867 (M)R University of Delhi, Delhi-110 007 6. STATUTE 7(1)(vi) The Librarian Delhi University Library System University of Delhi Delhi-110007 1 7. STATUTE 7(1)(vi) The Dean A-172, Sainik Colony 27666426 (O) Faculty of Arts Sector-49, Faridabaad 9891162053 (M) Department of Germanic & Romance [email protected] Studies. University of Delhi Delhi-110007 (Prof. Minni Sawhney) 8. The Dean C-705, Satisar Apts., 24110833 (O) Faculty of Applied Social Sciences Plot No.