Myanmar Security Outlook: Tatmadaw Under Stress? CHAPTER 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewership and Listenership Survey

VIEWERSHIP & Listenership Survey Lashio & North Okkalapa Research conducted by Ah Yo, Su Mon, Soe Win Myint with the FEBRUARY 2017 assistance of LRC in Lashio, Saitta Thukha Development Institute in REPORT WRITTEN BY: North Okkalapa, and Xavey Research Solutions. Anna Zongollowicz, PhD FOR FURTHER INFORMATION: Isla Glaister Country, Director of Search for Common Ground - Myanmar Email: [email protected] VIEWERSHIP & LISTENERSHIP SURVEY Lashio & North Okkalapa 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 TV 5 Radio 6 Social Media 6 Reaction to News 6 Conclusion 7 Recommendations 7 Listenership & Viewership Survey 8 Introduction 8 Youth 9 Media 9 Methodology 11 Sampling 12 Limitations 12 Findings 13 Demographics 13 TV Viewership 14 Radio Listenership 16 Social Media 17 Reaction to News 18 Conclusion 19 Recommendations 20 References 21 SEARCH FOR COMMON GROUND VIEWERSHIP & LISTENERSHIP SURVEY Lashio & North Okkalapa 3 CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 TV 5 Radio 6 Social Media 6 Reaction to News 6 Conclusion 7 Recommendations 7 Listenership & Viewership Survey 8 Introduction 8 Youth 9 Media 9 Methodology 11 Sampling 12 Limitations 12 Findings 13 Demographics 13 TV Viewership 14 Radio Listenership 16 Social Media 17 © Search for Common Ground - Myanmar (2017) Disclaimer Reaction to News 18 The research has been carried out with the financial assistance of the Peace Support Fund. Conclusion 19 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and in no circumstances Recommendations 20 refer to the official views of Search for Common Ground or the Peace Support Fund. References 21 SEARCH FOR COMMON GROUND VIEWERSHIP & LISTENERSHIP SURVEY Lashio & North Okkalapa 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The report contains findings from a quantitative survey examining TV viewership, radio listenership and social media usage, which was conducted in the third week of November 2016 in Lashio (Shan State) and North Okkalapa (Greater Yangon). -

Regional Reverberations from Regime Shake-Up in Rangoon.Qxd

Asia-PacificAsia-Pacific SecuritySecurity SStudiestudies RegionalRegional ReverberationsReverberations fromfrom RegimeRegime Shake-upShake-up inin RangoonRangoon Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Volume 4 - Number 1, January 2005 Key Findings The reverberations from the recent regime shake-up in Rangoon continue to be felt in regional capitals. Since prime minister Khin Nyunt was the chief architect of closer China-Burma strategic ties, his sudden removal has been interpret- ed as a major setback for China's strategic goals in Burma. Dr. Mohan Malik is a Professor with the Asia-Pacific Center for However, an objective assessment of China's strategic and eco- Security Studies. nomic needs and Burma's predicament shows that Beijing is His work focuses main- unlikely to easily give up what it has already gained in and ly on Asian Geopolitics through Burma. From China's perspective, Burma should be and Proliferation in Asia-Pacific region. His satisfied to gain a powerful friend, a permanent member of the most recent APCSS UN Security Council, and an economic superpower that comes publication is “India-China Relations: bearing gifts of much needed military hardware, economic aid, Giants Stir, Cooperate infrastructure projects and diplomatic support. and Compete ” The fact remains that ASEAN, India and Japan cannot compete with China either in providing military assistance, diplomatic support or in offering trade and investment benefits. With the UN-brokered talks on political reconciliation having reached a dead end, it might be worthwhile to start afresh with a dia- logue framework of ASEAN+3 (ASEAN plus China, India and Japan) on Burma. This would also put to test China's oft-stated commitment to multi- lateralism and Beijing's penchant for "Asian solutions to Asian problems". -

October Chronology (Eng)

October 2015, Chronology Summary of the Current Situation As of the end of October, there are 112 political prisoners incarcerated in Burma and 486 activists currently awaiting trial for political actions. Detained Facebook Activists Patrick Kum Jaa Lee and Chaw Sandy Tun Accessed October 2015 Table of Contents Month in Review Detentions Incarcerations Conditions of Detentions Demonstrations and Related Restrictions on Political and Civil Liberties Land Issues Key International and Domestic Developments Conclusion Links and Resources “There can be no national reconciliation in Burma, as long as there are political prisoners” October 2015, Chronology MONTH IN REVIEW This month, 10 political activists were arrested political prisoners is preventing the upcoming in total, eight of whom are detained. Thirty- election from being free and fair. One were sentenced, and eight were released. Despite concerns over the legitimacy of the Nine political prisoners are reported to be in upcoming election, new arrests continued this bad health. month. Lu Zaw Soe Win, Patrick Kum Jaa Lee The Letpadan case was still not resolved this and Chaw Sandy Tun were all arrested and month, and 61 students and activists remain detained for allegedly posting to Facebook detained for charges relating to their images or insults defaming the government and participation in the National Education Bill received charges either under the protests in March. Fortify Rights and the Telecommunications Law or the Electronic Harvard Law School International Human Transactions Law. Patrick Kum Jaa Lee and Rights Clinic released a report detailing the Chaw Sandy Tun remain in detention. Maung abusive tactics used by police officials in the Saungkha also received charges under the violent crackdown. -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID.GOV DECEMBER 2019 MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT | 1 JANUARY 2020 AT A GLANCE Myanmar’s ICOE Finds Insufficient Evidence of Genocide. The ICOE admits there is evidence that Tatmadaw soldiers committed individual war crimes, but rules there is no evidence of a systematic effort to destroy the Rohingya people. (Page 1) The ICJ Rules Myanmar Must Take Measures to Protect the Rohingya From Acts of Genocide. International observers laud the ruling as a major step toward fighting genocide globally, but reactions to the ruling in Myanmar are mixed. (Page 2) Fortify Rights Documents Five Cases of Rohingya IDPs Forced to Accept NVCs. The international community and the Rohingya condemned the cards, saying they are a means to keep the Rohingya from obtaining full citizenship rights by identifying them as “Bengali,” not Rohingya. (Page 3) During the Chinese President’s State Visit to Myanmar, the Two Countries Signed Multiple MoUs. The 33 MoUs that President Xi Jinping cosigned are related to infrastructure, trade, media, and urban development. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

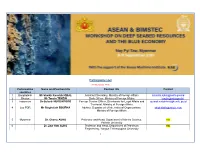

Participants List

Participants List (10 September 2019) Participating Name and Position title Position title Contact countries 1 Bangladesh Mr Sheikh Kaushik IQBAL Assistant Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs [email protected] 2 Bhutan Mr Tenzin TENZIN Desk Officer, Ministry of Foreign Affairs [email protected] 3 Indonesia Dr Gulardi NURBINTORO Foreign Service Officer, Directorate for Legal Affairs and [email protected] Territorial, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 4 Lao PDR Mr Singhalath BOUPHA Advisor, Department of International Organizations, [email protected] Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 Myanmar Dr. Cherry AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Marine Science, TBC Pathein University 6 Dr. Zaw Htet AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Petroleum TBC Engineering, Yangon Technological University 1 Participating Name and Position title Position title Contact countries 7 Dr. Zaw Min AUNG Executive Geologist, Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, [email protected] Ministry of Electricity and Energy 8 Dr. Zaw Moe AUNG Lecturer, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine TBC University 9 Dr. Mi Khin Saw AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Law, Dagon TBC University 10 Dr. Day Wa AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Geology, Yangon TBC University 11 Mr. Ngwe Zaw AUNG Deputy Director, Union Attorney General Office TBC 12 Dr. Cho Cho AYE Professor and Head, Department of Geology, East TBC Yangon University 13 Dr. Khin Chit CHIT Professor and Head, Department of Law, Yangon TBC University 14 H.E Dr. Myo Thein GYI Union Minister for the Ministry of Education TBC 15 Dr. Ko Ye HLA Professor, Department of Geology, Mawlamyine University TBC 16 Dr. -

Myanmar Security Outlook: a Taxing Year for the Tatmadaw CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4 Myanmar Security Outlook: A Taxing Year for the Tatmadaw Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction 2015 was a landmark year in Myanmar politics. The general election was held on 8 November and the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of Myanmar armed forces founder and independence hero General Aung San) won a landslide victory over the incumbent Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP; a military-backed party led by ex-military officers and President Thein Sein). This was an unexpected development that could challenge the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military. The Tatmadaw (literally “royal force”) or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) also faced a serious challenge to its primary security role when the defunct Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a renegade ethnic armed organization (EAO), unleashed a furious assault to take over the Kokang Self-Administered Zone (KSAZ; bordering China) leading to a drawn out war of attrition lasting several months and threatening Myanmar-China relations. Tatmadaw: fighting multiple adversaries Despite actively participating in the peace process, launched by President Thein Sein’s elected government since 2011, The MDS found itself engaged in fierce fighting with powerful EAOs in the northern, eastern and south-eastern border regions of Myanmar. In fact, except for the MNDAA, most of these armed groups that engaged in armed conflict with the MDS throughout 2015 were associated with EAOs which had been officially negotiating with the government’s peace-making team toward a nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) since March 2014. Moreover, almost all of them had some form of bilateral ceasefire arrangements with the government in the past. -

From Kunming to Mandalay: the New “Burma Road”

AsieAsie VVisionsisions 2525 From Kunming to Mandalay: The New “Burma Road” Developments along the Sino-Myanmar border since 1988 Hélène Le Bail Abel Tournier March 2010 Centre Asie Ifri The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the authors alone. ISBN : 978-2-86592-675-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THÉRÈSE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 - FRANCE 1000 - BRUXELLES, BELGIQUE PH. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 PH. : +32 (2) 238 51 10 FAX: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX: +32 (2) 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org China Program, Centre Asie/Ifri The Ifri China Program’s objectives are: . To organize regular exchanges with Chinese elites and enhance mutual trust through the organization of 4 annual seminars in Paris or Brussels around Chinese participants. -

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Updated March 18, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44570 U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Summary Major changes in Burma’s political situation since 2016 have raised questions among some Members of Congress concerning the appropriateness of U.S. policy toward Burma (Myanmar) in general, and the current restrictions on relations with Burma in particular. During the time Burma was under military rule (1962–2011), restrictions were placed on bilateral relations in an attempt to encourage the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, to permit the restoration of democracy. In November 2015, Burma held nationwide parliamentary elections from which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) emerged as the party with an absolute majority in both chambers of Burma’s parliament. The new government subsequently appointed Aung San Suu Kyi to the newly created position of State Counselor, as well as Foreign Minister. While the NLD controls the parliament and the executive branch, the Tatmadaw continues to exercise significant power under provisions of Burma’s 2008 constitution, impeding potential progress towards the re-establishment of a democratically-elected civilian government in Burma. On October 7, 2016, after consultation with Aung San Suu Kyi, former President Obama revoked several executive orders pertaining to sanctions on Burma, and waived restrictions required by Section 5(b) of the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-286), removing most of the economic restrictions on relations with Burma. On December 2, 2016, he issued Presidential Determination 2017-04, ending some restrictions on U.S. -

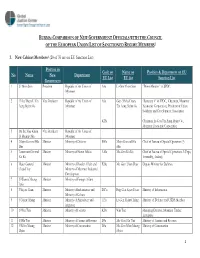

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

China in Burma

CHINA IN BURMA : THE I NCREASING I NVESTMENT OF CHINESE MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS IN BURMA’S HYDROPOWER, OIL AND NATURAL GAS, AND MINING SECTORS UPDATED: September 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EarthRights International would like to thank All Arakan Student & Youth Congress, Arakan Oil Watch, Burma Relief Center, Courier Research Associates, Images Asia E-Desk, Kachin Development Networking Group, Kachin Environmental Organization, Karen Rivers Watch, Karenni Development Research Group, Lahu National Developmen t Organization, Mon Youth Progressive Organization, Palaung Youth Network Group, Salween Watch Coalition, Shan Sapawa and Shwe Gas Movement, for providing invaluable research assistance and support for this report. Free reproduction rights with citation to the original. EarthRights International (ERI) is a non-government, non- profit organization that combines the power of the law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment, which we define as “earth rights.” We specialize in fact-finding, legal actions against perpetrators of earth rights abuses, training grassroots and community leaders, and advocacy campaigns. Through these strategies, ERI seeks to end earth rights abuses, to provide real solutions for real people, and t o promote and protect human rights and the environment in the communities where we work. Southeast Asia Office U.S. Office P.O. Box 123 1612 K Street NW, Suite 401 Chiang Mai University Washington, D.C. Chaing Mai, Thailand 20006 50202 Tel: 1-202-466-5188 Tel: 66-1-531-1256 Fax: 1-202-466-5189