Independence 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of Possibilities

NONPROFIT ORG THE HEINZ ENDOWMENTS issue 2 2015 SPECIAL EDITION: p4 PITTSBURGH US POSTAGE Howard Heinz Endowment Vira I. Heinz Endowment PAID 625 Liberty Avenue PITTSBURGH PA 30th Floor PERMIT NO 57 Pittsburgh, PA 15222-3115 The Power of 412.281.5777 Possibilities www.heinz.org Pittsburgh leaders envision a brighter, more sustainable future for the city, and they are drawing on inspiration from across the globe to develop strategies that will make the transformation a reality. Hard at play. page 40 This magazine was printed on Opus Dull, which has among the highest post-consumer waste content of any premium coated paper. Opus is third-party certifi ed according to the chain-of-custody standards of FSC®. The electricity used to make it comes from Green e-certifi ed renewable energy. BOROUGH BOOSTS NEIGHBORHOOD RE-CREATION MONEY MATTERS PLAY TIME 55541_cvrC2.indd541_cvrC2.indd 1 77/28/15/28/15 55:00:00 AMAM 43 BOARD AND STAFF RECOGNITIONS THE ECONOMIC GAP Dr. Shirley Malcom, a Heinz Endowments board member, Two separate reports released earlier this year was one of fi ve people from across the country selected by U.S. revealed the ongoing socioeconomic disparities News & World Report for the 2015 STEM Leadership Hall of experienced by minorities, particularly African Fame. Dr. Malcom is head of education and human resources programs for the American Association for the Advancement Americans, in the Pittsburgh region. “Pittsburgh’s of Science. She and the other honorees were recognized as Racial Demographics 2015: Differences and inspirational leaders who have achieved measurable results Disparities,” a Heinz Endowments–funded in the science, technology, engineering and math fi elds; inside study produced by the University of challenged established processes and conventional wisdom; Pittsburgh’s Center on Race and Social and motivated aspiring STEM professionals. -

ANNUAL REPORT AUGUST 2016 Board of Directors Staff

ANNUAL REPORT AUGUST 2016 Board of Directors Staff Lisa Barsom Kevin Hutchison Michael Baltzer* Assistant Vice Chancellor, President & CEO, Director, Marketing, Academic Affairs, University Health Monitoring Systems, Inc. Communications & Alumni of Pittsburgh Health Sciences Kelly McCormick Sarah Collier Phillip Beck Director, Corporate Human Resources, Faculty, Site Director, M. Baltzer J. Kamara Vice President, Ariba Network, Ariba, Inc. Giant Eagle Public Allies Pittsburgh Peter Blasier Sharon McDaniel Greg Crowley* Partner, Reed Smith Founder, President & Chief Executive President & CEO Officer, A Second Chance, Inc. Lynn Banaszak Brusco* DaVonna Graham* Executive Director, Stephan Mueller Facilitator, S. Collier R. Lobley Disruptive Health Technology Institute, Chief Operating Officer, Thrill Mill NEXT Neighborhood Leaders Carnegie Mellon University Margot Nikitas* Lynn Hein Wayne B. Cobb II* Associate General Counsel, Business Manager Senior Partner, Cobb Counsel Illinois Education Association Jennifer Holliman* Greg Crowley* Raymond Prushnok Director, Operations G. Crowley M. Organ President & CEO, Coro Pittsburgh Senior Director, Medicare Special Needs Plans, Jamillia Kamara Justin Ehrenwerth* UPMC Health Plan Community Liaison Executive Director, Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council Chloe Velasquez* Rebecca Lobley* President, Sabio Springs, Inc. Program Manager, D. Graham M. Parker Richard Ekstrom, Chairman Public Allies Pittsburgh Principal, Socius Partners, LLC Melanie Organ Christian Farmakis Administrator Shareholder, Business Services Group, Babst Calland, Mary C. Parker* President, Solvaire Technologies, L.P. Facilitator, Women in Leadership L. Hein M. Sider-Rose Michael Sider-Rose Faculty, Senior Director, Programs & Learning Development BOARD AND STAFF J. Holliman *Alumni 1 A letter from our CEO Pittsburgh is in the midst of a remarkable transformation. Our economy has endured a major recession only to come out stronger. -

The Ardmore Corridor Is Marked for Big Changes

the inside BOROUGH 3 WCDC 4 SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 7 VOL. 9 NO. 6 March 2016 A FREE COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER BRINGING YOU GOOD NEWS ABOUT WILKINSBURG The Ardmore Corridor Is Marked for Big Changes Officers Yuhouse and Jarko K-9 Officer Passes Away “It is with great sadness that we Wilkinsburg announce the passing of our beloved K-9 Officer, Jarko. Jarko died unexpectedly yesterday as a result of complications following surgery,” the Wilkinsburg Police Department posted online on January 27. Jarko served with the department and his handler, Office Doug Yuhouse for eight years and was responsible for countless photo by Drew Gordon drug arrests and criminal apprehensions. He did many public presentations for As spring rapidly approaches and we later in 2016. In all, the Borough will Youth and Citizens Police Academies. anxiously await the rebirth that comes spend up to $750,000 on demolition— Jarko served the Wilkinsburg Police with the melting snow and warmer made up of a $250,000 grant of CITF Department and the community with temperatures, Wilkinsburg too moves (Community Infrastructure and Tourism courage and distinction, and he will be toward a rebirth or renaissance of one of Funds) received from the Redevelopment greatly missed. our major gateway corridors. Authority of Allegheny County (with the In the upcoming months, Ardmore strong support of Senator Costa) and WCDC Receives Initial Funding Boulevard, from Franklin Avenue to $500,000 from a recent municipal bond. for Train Station, See story on Swissvale Avenue (this includes the 1200 This project stems from the creation of page 4. -

Men's Hoops Media Guide 15-16.Pub (Read-Only)

Table of Contents PITT-JOHNSTOWN PRIMARY MEDIA OUTLETS Track the Mountain Cats WJAC-TV 6 SPORTS TRIBUNE-DEMOCRAT Jordan Conigliaro Shawn Curtis, Mike Mastovich Through Social Media 49 Old Hickory Lane 47 Locust Street Johnstown, Pa. 15905 Johnstown, Pa. 15901 all season… (814) 255-7651 (814) 532-5080 Fax: (814) 255-7658 Fax: (814) 539-1409 SOMERSET DAILY AMERICAN ALTOONA MIRROR 334 West Main Street P.O. Box 2008 Somerset, Pa. 15501 Altoona, Pa. 16603 (800) 452-0823 (800) 222-1962 Fax: (814) 445-2935 Fax: (814) 946-7540 WTAJ-TV 10 SPORTS PGH. POST-GAZETTE On the Pitt-Johnstown P.O. Box 10 50 Blvd. Of The Allies Altoona, Pa. 16603 Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222 Website at (800) 762-6053 (412) 263-1621 Fax: (814) 946-4763 Fax: (412) 263-1926 www.pittjohnstownathletics.com PGH. TRIBUNE-REVIEW INDIANA GAZETTE (888) 748-8742 (800) 262-3077 Fax: (412) 320-7964 Fax: (724) 465-8267 BEDFORD GAZETTE THE ADVOCATE 424 W. Penn Street 147 Student Union Bldg. P.O. Box 671 Johnstown, Pa. 15904 (814) 623-1151 (814) 269-7470 (814) 623-5055 On Facebook at facebook.com/pages/Pitt-Johnstown- Athletics Design and Layout: Chris Caputo-Sports Information Director Ashley Grego-Sports Information Intern Cover Design and Layout: Ali Single Contributing Editors: Bob Rukavina, Patrick Grubbs And on Twitter at Photography: @MtnCatAthletics Front Cover: Ali Single Inside and Back Cover Photographs: Ali Single Inside Pages: Pitt-Johnstown User Services, Ali Single, The Tribune-Democrat, The Advocate Printing: Interior: Pitt-Johnstown Print Shop 1 Head Coach Bob Rukavina YEAR RECORD OVERALL PCT. -

Wilkinsburg School District and School District of Pittsburgh AMENDED LETTER of AGREEMENT

Wilkinsburg School District and School District of Pittsburgh AMENDED LETTER OF AGREEMENT Following the decision of the Wilkinsburg School District to close and discontinue its middle / high school program at the conclusion of the 2015/16 school year, pursuant to Section 1607 of the Public School Code, 24 P.S. § 16-1607, Wilkinsburg School District assigned pupils in grades seven through twelve to attend the Pittsburgh Public Schools’ George Westinghouse Academy, also known as Westinghouse 6-12 School (hereinafter, “Westinghouse”), as to which Wilkinsburg School District and Pittsburgh Public Schools entered into a Letter of Agreement. The following terms serve as the parties’ amended agreement, to be further supplemented as necessary, for the assignment of Wilkinsburg School District students in grades seven through twelve to attend school in the Pittsburgh Public Schools pursuant to Section 1607 of the Public School Code: 1. Assignment of Pupils. In accordance with Section 1607 of the Public School Code, Wilkinsburg School District reaffirms that students in grades seven through twelve shall be assigned by Wilkinsburg School District to attend high school at Westinghouse. 2. Term. The term of this amended agreement shall commence with the 2021-22 school year. This agreement is cancellable by either party upon notice to the other party provided not later than less than eighteen months in advance, but not effective sooner than the conclusion of the 2026-27 school year, provided, that the termination of this agreement shall not impair any rights Wilkinsburg School District students otherwise have to attend Pittsburgh Public Schools as provided by law upon the discontinuance by Wilkinsburg School District of its middle / high school program. -

Edward J. Blotzer Is Presenting This Testimony Principal of The

Testimony presented before the Select Cornmi ttee Of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Resolution 495 Erie, PA August 3 I,2000 Edward J. Blotzer is presenting this testimony 1 would like to thank Representative Roherer for the opportunity to address this committee today on the PSSA test of assessment. I am currently the Associate Principal of the Wilkinsburg High School. Prior to that, I was a classroom teacher for the past thirty-one years. It is from that prospective that I wanted to address this issue. As a result of our students not doing well on this test alone, I am an Empowered Teacher that feels totally disemboweled. You have made this test the gold standard by which everyone is to be judged. Despite the fact that our students did not do well on this test, they are not failures and I will explain the reasons I believe the scoring was not indicative of the ability of the students we have attending our schoofs. Last year, our valedictorian received a scholarship to Duke University where she is now attending, majoring in premed. Our salutatorian is attending Northwestern University majoring in pre-law I communications. Many others are attending such schools as Kent State, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and other four year colleges. Many of the graduates from the last class are attending Allegheny County Community College both because of its tuition structure and the ability to transfer credits to four year colleges. Additionally, others are attending various proprietary schools First, this test, as you already know, has not been normed {standardized) through any national organization such as Princeton Educational Testing Service. -

2013 Heinz Fellows

3 MODELS OF SUCCESS OPENING ESSAY | DOUGLAS ROOT PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTHA RIAL Stacy Innerst 29 INVESTMENT The problem is 6 ÷ 2. Actually, that is the small problem that has led Sean Means to understand MODELS the magnitude of the Big Problem. Its scope is revealed in a study session with a soon-to-be 10th-grader in one of Pittsburgh’s most academically troubled public high schools. The student is puzzled — his face scrunched as he blurts OF out a series of answers, each of them a guess, and each guess wrong. “How about 9 x 8?” Doesn’t know. “How about 5 x 3?” Silence. SUCCESS A week later, 30-year-old Means is sitting in a Starbucks in Shadyside. It is a two-mile drive and a 1,000-light-year cultural shift from the struggling OPENING ESSAY | DOUGLAS ROOT PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTHA RIAL teen in the summer program at Pittsburgh Westinghouse. The mammoth Classical Revival building that once served thousands of students now draws about 530 sixth-to-12th graders from some of the poorest neighborhoods. When a mentoring rescue The racial breakdown: 99 percent African American, 1 percent other. team of young, black, college- That statistic helps explain why Means, African American and a college educated men was unleashed graduate from Atlanta whose career path has taken him from Washington, D.C. to connect with students in to New Zealand, now is sitting in a Pittsburgh coffee bar fretting over one one of Pittsburgh’s most lost student. “Look — he’s a good kid, but he just doesn’t know it,” Means says, troubled schools, some dust thumping long fingers on the table for emphasis. -

Wilkinsburg School District and School District of Pittsburgh

Wilkinsburg School District and School District of Pittsburgh LETTER OF AGREEMENT The Wilkinsburg School District, due to low enrollment, cannot provide the academic offerings required to provide students adequate opportunities to receive a quality education and, therefore, is considering closing and discontinuing its middle / high school program (grades seven through twelve). In the event of the closure and discontinuance of the Wilkinsburg School District’s middle / high school program, pursuant to Section 1607 of the Public School Code, 24 P.S. §16-1607, Wilkinsburg School District will assign the pupils to a high school and provide adequate transportation thereto. The following terms serve as the parties’ agreement, to be further supplemented as necessary, for the assignment of Wilkinsburg School District students in grades seven through twelve to attend school in the Pittsburgh Public Schools pursuant to Section 1607 of the Public School Code: 1. Assignment of Pupils. Upon the closure by Wilkinsburg School District of its middle / high school, in accordance with Section 1607 of the Public School Code, Wilkinsburg School District students in grades seven through twelve shall be assigned by Wilkinsburg School District to attend high school in the Pittsburgh Public Schools’ George Westinghouse Academy, also known as Westinghouse 6-12 School (hereinafter, “Westinghouse”). 2. Implementation. The terms of this agreement shall be implemented at the commencement of the first school year following and in the event of the closure by Wilkinsburg -

Tastes of Wilkinsburg Finding Unique and Delicious Food Nearby; the Second in a Series

the inside BOROUGH 3 WCDC 4 SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 7 VOL. 9 NO. 2 October 2015 A FREE COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER BRINGING YOU GOOD NEWS ABOUT WILKINSBURG Tastes of Wilkinsburg Finding unique and delicious food nearby; the second in a series. It’s been nine months since Markie Maraugha and Greg Stocke reopened Nancy’s as Nancy’s East End Dinner. They have preserved the retro decor, personable service, and classic diner food, but they have added their own flair. For one thing, they have been intentional about featuring local sources: 2014 filming process of Southpaw brought trailers and cameras to Wallace, Penn and Rebecca Avenues. Fortune’s Tanzanian peaberry coffee, Wilkinsburg Lights! Camera! Wilkinsburg! In 2012, CNN wrote that Pittsburgh his former glory; Tick Wills, the trainer is “fast becoming the Tinseltown of he uses to get his life back on track, and the East.” With 3 movies filming in Jordan Mains, Billy’s manager. the Borough in 15 months, perhaps Earlier this year, the Blackridge area of Wilkinsburg should be known as the Wilkinsburg was covered in white; despite Tinseltown of the Eastern Suburbs! the winter that would not die, the crew In July and August of 2014, Southpaw of Let It Snow had to use the fake stuff —now in theaters—used Wilkinsburg to re-create a snowy Christmas Eve that locations as background for the story transforms one small town. Since retitled of Billy Hope, a successful boxer sent Love the Coopers, the all-star cast includes into a tailspin by personal tragedy. Jake Alan Arkin, John Goodman, Ed Helms, Gyllenhaal, Forest Whittaker and 50 Diane Keaton, Anthony Mackie, Amanda Cent graced the streets of the Borough Seyfried, June Squibb, Marisa Tomei and as Billy Hope, the boxer trying to reclaim continued on page 3 Community Meeting about Wilkinsburg and Pittsburgh Public School Partnership Photo by DrewPhoto by Gordon Co-owner Markie in a misnomered t-shirt. -

Inside Borough 3 WCDC 4 School District 5 Recycling Calendar 6 Chamber of Commerce 7

the inside Borough 3 WCDC 4 SChool DiStriCt 5 reCyCling CalenDar 6 ChamBer of CommerCe 7 VOL. 5 NO. 6 March 2012 A Free Community newsletter Bringing you good news ABout wilkinsBurg Trees Mean Business in Wilkinsburg Nine Mile Run Watershed Association Working to Plant New trees have been sprouting up in the sidewalks all over the Borough over the last year, as part of the Wilkinsburg TreeVitalize program. The Nine Mile Run Watershed Association (NMRWA) is the local delivery partner in this initiative to plant 500 new street trees by fall 2012. The initiative has included removal of trees, also, particularly in the business district on WilkinsburgPenn Avenue. Some earmarked for removal are mature and have reached the end of their useful lives, while other younger trees simply never thrived—either because they were vandalized or Wilkinsburg Girl Scouts, Troop 51058, have adopted four abandoned lots on the corner of Tioga and Wood Streets. While the weren’t tough enough to survive in the urban borough has been demolishing the remaining structures on the property, the girls have been planning what can be done with this continued on page 6 gateway property. They have met with experts and made a wish list, including a lit wall and fruit-bearing trees. On a snowy February 4, the girls installed painted cutouts of themselves on the lots to symbolize the beauty and hope they have for this space. The troop has been led by sisters Donna Alexander and Kim Olday (pictured back center) since 2007. Girl scouts who were present that day include Taiah Trent-Hill, Neriah Alexander, Sanaa Langford, Violet Shattuck, Poppy Shattuck, Cori Reese, Cierra Epps, Annette Payne, Hannah Wilson, Abigail Wilson, Rachel Wilson, Danielle Owens, Tiara Cohen. -

: : ^ Archive Reporting Service

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIO IN RE: HOUSE RESOLUTION 495, PENNSYLVANIA SYSTEM OF SCHOOL ASSESSMENT THE BEHREND COLLEGE, PENN STATE ERIE REED UNION BUILDING, ROOM 114 5091 STATION ROAD ERIE, PENNSYLVANIA THURSDAY, AUGUST 31, 2000, 9:04 A.M. BEFORE: HON. SAMUEL E. ROHRER, CHAIRMAN HON. DARYL D. METCALFE HON. PHYLLIS MUNDY HON. SARA G. STEELMAN HON. THOMAS J. SCRIMENTI HON. THOMAS L. STEVENSON HON. THOMAS F. YEWCIC JEAN M. DAVIS REPORTER-NOTARY PUBLIC /:: ^ ARCHIVE REPORTING SERVICE t - ' JH 2336 N. Second Street (717)234-5922 E9BJ Harrisburg, PA 17110 FAX (717) 234-6190 » ^A-_ INDEX WITNESS PAGE Joseph Morrison 4 John Shaffer 61 Margie Jorgensen 89 Edward Blotzer 144 Marlene Tobin 183 Dr. James Barker 221 CHAIRMAN ROHRER: Good morning and welcome to the fourth Committee hearing scheduled under House Resolution 495, the purpose of doing fact finding on Pennsylvania Assistance on State Assessments. We are glad to be in Erie today on the northwestern part of the State, and we are looking forward to another day of good testimony as we attempt as a Committee to pull together the information that we need in order to come up with findings and recommendations on this topic that deals with the testing of our students and public schools in Pennsylvania. As we have been seeing, the days have been full and the testimony provided has prompted many questions. And, therefore, in order to try and keep us on schedule as much as possible, I'd like to get right to it. I'd like all of the Members of the Committee that are here this morning to introduce themselves, first of all, for the record and a little bit about where they represent and so fourth. -

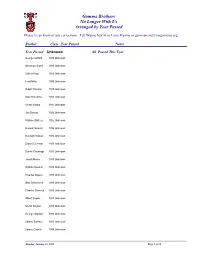

Gamma Brothers No Longer with Us Arranged by Year Passed

Gamma Brothers No Longer With Us Arranged by Year Passed Please let us know of any corrections. Tell Wayne Norris or Larry Kuzma or [email protected] Brother Class Year Passed Notes Year Passed Unknown 46 Passed This Year George Gifford 1930 Unknown Sherman Horne 1930 Unknown Gilbert Hoyt 1930 Unknown Fred Mller 1930 Unknown Ralph Thomas 1930 Unknown Sam Schettino 1931 Unknown Victor Vassia 1931 Unknown Jim Sinclair 1932 Unknown William Slattery 1932 Unknown Russell Switzer 1932 Unknown Kenneth William 1932 Unknown s Daniel Coleman 1933 Unknown Darrell Dovenspi 1933 Unknown ke Jewell Moore 1933 Unknown William Russell 1933 Unknown Charles Sayers 1933 Unknown Blair Schuckers 1933 Unknown Charles Sherrieb 1933 Unknown Albert Snyder 1933 Unknown Merrill Snyder 1933 Unknown George Startzel 1933 Unknown James Sweeny 1933 Unknown James Cassel 1934 Unknown Monday, January 18, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Brother Class Year Passed Notes Charles Frederic 1934 Unknown k Eugene Hartman 1934 Unknown Maurice Moffatt 1934 Unknown Tryus Bartley 1935 Unknown Leo Brown 1935 Unknown Emil Rosenzwei 1935 Unknown g Willard Simpson 1935 Unknown Bryon Gilfillan 1936 Unknown Thomas Hosack 1936 Unknown Joseph Kenny 1936 Unknown William Byers 1937 Unknown Charles Hetrick 1937 Unknown Zeigy Kunczews 1937 Unknown ki Marcus Priester 1937 Unknown Charles Reed 1937 Unknown Richard Sloan 1937 Unknown Theodore McDo 1938 Unknown nald Bronie Smolak 1938 Unknown Joseph Andreo 1939 Unknown Paul Griffin 1939 Unknown John Sershen 1939 Unknown Paul Trunk 1939 Unknown Harry Wozniak 1939 Unknown Year Passed 2021 1 Passed This Year Monday, January 18, 2021 Page 2 of 60 Brother Class Year Passed Notes James Alcorn 1968 2021 Jim Alcorn, 75, of Irwin, passed away Wednesday, Jan.