Unmet Needs for Care and Support for the Elderly in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Conflict Re-Interview (Emergency Response

This PDF generated by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 11:01:05 AM Sections: 11, Sub-sections: 0, Questionnaire created by akuffoamankwah, 8/2/2017 7:42:50 PM Questions: 130. Last modified by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 3:00:07 PM Questions with enabling conditions: 81 Questions with validation conditions: 14 Shared with: Rosters: 3 asharma (never edited) Variables: 0 asharma (never edited) menaalf (never edited) favour (never edited) l2nguyen (last edited 8/9/2017 8:12:28 PM) heidikaila (never edited) Nigeria Conflict Re- interview (Emergency Response Qx) [A] COVER No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 18, Static texts: 1. [1] DISPLACEMENT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [2] HOUSEHOLD ROSTER - BASIC INFORMATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [3] EDUCATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 3. [4] MAIN INCOME SOURCE FOR HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [5] MAIN EMPLOYMENT OF HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6, Static texts: 1. [6] ASSETS No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 12, Static texts: 1. [7] FOOD AND MARKET ACCESS No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 21. [8] VULNERABILITY MEASURE: COPING STRATEGIES INDEX No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [9] WATER ACCESS AND QUALITY No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 22. [10] INTERVIEW RESULT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 8, Static texts: 1. APPENDIX A — VALIDATION CONDITIONS AND MESSAGES APPENDIX B — OPTIONS LEGEND 1 / 24 [A] COVER Household ID (hhid) NUMERIC: INTEGER hhid SCOPE: IDENTIFYING -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author(S

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria. May, 2015 i Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................................v Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................................................................vii Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................viii 1.0 Background ............................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Objectives of the Mapping Project ..................................................................................................2 1.3 Justification for the Survey ..................................................................................................................2 2.0. Mapping Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 -

Sexual Behaviours and Experience of Sexual Coercion Among In-School Female Adolescent in Southwestern Nigeria

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/19000851; this version posted July 3, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . TITLE OF RESEARCH: SEXUAL BEHAVIOURS AND EXPERIENCE OF SEXUAL COERCION AMONG IN-SCHOOL FEMALE ADOLESCENT IN SOUTHWESTERN NIGERIA *FIRST AUTHOR: BABATUNDE OWOLODUN SAMUEL (BS.c, MPH) ADDRESS: FACULTY OF PUBLIC HEALTH, DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN NUTRITION, UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN, NIGERIA EMAIL: [email protected] SECOND AUTHOR: ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DR. SANUSI R.A (MBBS, MSc, PhD) ADDRESS: FACULTY OF PUBLIC HEALTH, DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN NUTRITION, UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN, NIGERIA EMAIL: [email protected] NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/19000851; this version posted July 3, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . ABSTRACT Most people begin their sexual relationship during adolescence and some get involved in risky life threatening behaviors such as unwanted pregnancies, abortions and sexually transmitted infections. This study was therefore designed to understand the patterns of female adolescents sexual behaviours and sexual coercion experience. A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out among 1227 in-school adolescents in the three senatorial district of Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. -

Characterization and Analysis of Medical Solid Waste in Osun State, Nigeria

African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology Vol. 5(12), pp. 1027-1038, December 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJEST DOI: 10.5897/AJEST11.130 ISSN 1996-0786 ©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Characterization and analysis of medical solid waste in Osun State, Nigeria O. O. Fadipe 1, K. T. Oladepo 2*, J. O. Jeje 2 and M. O. Ogedengbe 2 1Department of Civil Engineering, Osun State College of Technology, Esa-Oke, Osun State, Nigeria. 2Department of Civil Engineering, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. Accepted 1 December, 2011 This paper reports the study of quantum and characterization of medical solid wastes generated by healthcare facilities in Osun State. The work involved administration of a questionnaire and detailed studies conducted on facilities selected on the basis of a combination of purposive and random sampling methods. The results show that the facilities are well spread among the 30 Local Government Areas; that the total quantity of medical waste generated in the state is 2672 kg/day and when domestic wastes are included the total is 5832 kg/day; that the medical wastes are not being properly disposed of as pathology wastes such as unclaimed dead bodies, placentas, umbilical cords are being dumped into unlined pits and other wastes in open dumps. A centralised system is proposed state–wide involving use of incinerators, landfills, aerobic lagoons, and reed beds. The Federal Ministry of Environment has responsibility to push for development of legislation and codes of practice that would guide facilities to achieve waste segregation, packaging in colour-coded and labeled bags, safe transportation and disposal of medical waste. -

Ethnomedicinal Use of Plant Species in Ijesa Land of Osun State, Nigeria

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 12: 164-170. 2008. Ethnomedicinal Use of Plant Species in Ijesa Land of Osun State, Nigeria J. Kayode1, L. Aleshinloye1 and O. E. Ige2 1Department of Plant Science, University of Ado-Ekiti, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Nigeria Issued 15 March 2008 ABSTRACT A combination of social survey and direct field observation was used to identify the medicinal plant species used in Ijesa land of Osun State, Nigeria. Voucher specimens of the species were obtained and the relative abundance for each of the identified botanical species was determined. A total of 45 plant species belonging to 30 families were identified. Our survey indicated they were used in the control of 22 diseases. Tribal information of these species is passed from one generation to another. These species were found to have multiple uses in the study area. Only 29% of the species were cultivated in the study area. A considerable proportion of these plant species were extracted predatorily and collections were done indiscriminately without consideration for size and age. At present, only 47% of the medicinal plants fall in the ‘abundant’ category for this study area. Most of these abundant species were cultivated for their fruits, seeds, leaves or vegetables. Finally, strategies that would enhance the conservation of the species in the study area were proposed. INTRODUCTION The Ijesa are a distinct ethnic Yoruba indigenous group in Osun State, Nigeria. They are found in local government areas in Ilesa West, Ilesa East, Oriade, Obokun and Atakumosa. Ijesa, like other Yoruba groups, cherished and preserved their culture seriously (Kayode 2002). -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

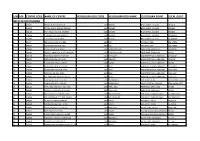

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

S/N S/N Centre Code Name of Centre Neigbourhood Code

S/N S/N CENTRE CODE NAME OF CENTRE NEIGBOURHOOD CODE NEIGBOURHOOD NAME CUSTODIAN POINT LOCAL GOVT NECO OFFICE OSOGBO 1 1 240071 IBOKUN HIGH SCH,IBOKUN 2437 IBOKUN NECO OFFICE, OSOGBO OBOKUN 2 240087 ATAOJA SCH OF SCIENCE,OSOGBO 2406 OSOGBO NECO OFFICE, OSOGBO OSOGBO 3 240190 BAPT GIRLS HIGH SCH, OSOGBO 2406 OSOGBO NECO OFFICE, OSOGBO OSOGBO 4 240078 ST MARKS HIGH SCH,OSOGBO 2406 OSOGBO NECO OFFICE, OSOGBO OLORUNDA 5 240077 C.A.C HIGH SCH, GBONMI 2406 OSOGBO NECO OFFICE, OSOGBO OLORUNDA 6 24147 EDE MUSLIM HIGH SCH,EDE 2405 EDE SKYE BANK, EDE EDE NORTH 7 240017 ADVENTIST HIGH SCH, EDE 2405 EDE SKYE BANK, EDE EDE NORTH 8 240061 ST PAUL HIGH SCH, ILOBU 2424 IFON ERIN/ILOBU FIRST BANK, ERIN-OSUN IREPODUN 9 240083 OROLU COMM HIGH SCH,IFON-OSUN 2424 IFON ERIN/ILOBU FIRST BANK, ERIN-OSUN OROLU 10 240103 GBONGAN/ODEOMU HIGH SCH 2401 AYEDAADE MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN AYEDAADE 11 240065 AYEDAADE HIGH SCH, IKIRE 2425 IREWOLE MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN IREWOLE 12 240126 ST ANTHONY COLLEGE, IKOYI 2430 ISOKAN MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN ISOKAN 13 240057 METHODIST HIGH SCH, ILESA 2421 ILESA MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN ILESA WEST 14 240058 OGEDENGBE HIGH SCH, ILESA 2421 ILESA MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN ILESA WEST 15 240056 OBOKUN HIGH SCH, ILESA 2421 ILESA MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN ILESA EAST 16 240021 THE APOSTOLIC HIGH SCH, ILESA 2421 ILESA MAINSTREET BANK, GBONGAN ILESA EAST 17 240005 ATAKUMOSA HIGH SCH, OSU 2431 ATAKUMOSA SKYE BANK, ILE-IFE ATAKUMOSA EAST 18 240004 COMM HIGH SCH, IPERINDO 2431 ATAKUMOSA POLICE STATION, IPERINDO ATAKUMOSA EAST 19 240144 IPETU-IJESA -

Evaluation of the School Health Programme Among Primary Schools in Ilesa East Local Government Area of Osun State, Nigeria

EVALUATION OF THE SCHOOL HEALTH PROGRAMME AMONG PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN ILESA EAST LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF OSUN STATE, NIGERIA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL COLLEGE OF NIGERIA, IN PART FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE COLLEGE IN PAEDIATRICS. BY OLATUNYA, Oladele Simeon M.B.B.S. (UNILORIN 2000) MAY 2011 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this work is original unless otherwise acknowledged. The work has not been presented to any other college for Fellowship award nor, has it been published or submitted for publication elsewhere. Sign Date ----------------------- ------------------ Olatunya Oladele Simeon 2 CERTIFICATION We hereby certify that this study was done by Dr. OLATUNYA OLADELE SIMEON, of the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex Ile Ife and that the dissertation was written under our supervision. Supervisor Signature------------------ Name- Dr. SBA Oseni Status –Senior Lecturer/ Consultant Department of Paediatrics and Child Health OAUTHC Ile Ife Co- supervisor Signature-------------------- Name- Prof. O.A. Oyelami Status- Professor/ Consultant Department of Paediatrics and Child Health OAUTHC Ile Ife 3 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the glory of God, my wife, my parents, Tijesunimi our child and all other children of the world. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I hereby acknowledge with profound gratitude the efforts of my supervisors; Dr SBA Oseni and Prof. O.A. Oyelami for their supports during the study. I also appreciate the assistance rendered by Professors G.A. Oyedeji, J.A. Owa and E.A. Adejuyigbe as well as Drs. N.A Akani, T. A. Aladekomo, J.A. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Male Attitudes to Cases of Unwanted Pregnancy and Their Involvement in Abortion Decision-Making in Southwest Nigeria

Male Attitudes to Cases of Unwanted Pregnancy and their Involvement in Abortion Decision-Making in Southwest Nigeria In Nigeria, contraceptive knowledge is low and access to family planning services is poor. The 2003 NDHS results indicate that while 13 percent of currently married women are using a method of family planning, only 8 percent are using a modern method. The 2003 NDHS shows that knowledge of contraception is low in the country and women may be at risk of unwanted pregnancy if their family planning needs are not met. Consequently, cases of unplanned pregnancies, especially among young unmarried women are increasingly common. Studies have shown that high incidence of unsafe abortion exists among students who resort to illegal abortion to avoid expulsion from school (WHO, 1994; Becker et al., 1992), ‘when they experience contraceptive failure’ (Okonofua et al, 1996) and for financial concerns and fear of social reprisal because of an out-of-wedlock pregnancy (Makinwa-Adebusoye, 1989). Women who resort to abortion are most likely to be adolescents and women under age 25 years (Barker and Khasiani, 1995). However, cases of unwanted pregnancies and abortions are not peculiar to young unmarried adolescents alone, many of the married women also engage in illegal and clandestine abortions for diverse reasons. For instance in Ghana, studies revealed that out of 900 women seeking an induced abortion or reporting complications from induced abortion, more than half (about 55%) were married and one-fourth were adolescents (WHO, 1994a). A common reason mostly given by women for unwanted pregnancy and eventual termination was poor timing of the pregnancy or the need to space births better. -

Osun State HIV/AIDS Programme Development Project (HPDP 2)

Osun State HIV/AIDS Programme Development Project (HPDP 2) (World Bank Assisted) Ida Credit No: 4596-N6 Osun State Agency for the Control of Aids (O-Saca) Office of the Governor, No 7C, Fagbewesa Street, Osogbo, Osun State Call for Expression of Interest for the Implementation of Osun State HIV/AIDS Fund (HAF) Issuance Date: 09/04/2013 Background Osun State Agency for the control of AIDS (O-SACA) has received financing from the World Bank toward the cost of the second HIV/AIDS Programme Development Project (HPDP) 2 and intends to apply part of the proceeds for consultant services. Assignment Description & Services Requested (Scope of Work) This is a call for Expression of Interest from qualified and competent NGOs, FBOs, CBOs, Support Groups and PSOs that are currently working in Osun State to provide support to Osun SACA in project implementation for a period of two years. Please note that the prioritized geographic coverage areas are subject to change in line with emerging evidence about the HIV epidemic in the state. Organizations are expected to identify and work with any or all specified target populations within the specified geographic coverage areas to deliver evidence based HIV intervention packages in line with international standard and best practices. HIV Prevention of New Infections 1. Most at Risk Populations (MARFs) CSOs are required to identify and work with the Most At Risk Populations within priority LGAs listed below delivering specific services as follows: 1. Target population: Female Sex Workers 2. Geographic Coverage Area; Olorunda LGA, Osogbo LGA, Ilesa East LGA, Ilesa West LGA, Ejigbo LGA, Ife Central LGA.