Traditional Land Use Study Report for the Proposed Trans Mountain Pipeline Ulc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Saskatchewan Region Surface Water Quality Management Framework

North Saskatchewan Region Surface Water Quality Management Framework A surface water quality management framework (framework) is being developed for the North Saskatchewan Region. The framework establishes an approach for monitoring and managing the cumulative impacts of human activities on water quality in the North Saskatchewan and Battle rivers. Cumulative effects management was first introduced in the North Saskatchewan Region with the Water Management Framework for the Industrial Heartland and Capital Region, which was developed in 2008 to address anticipated development in the Capital Region. At that time, government and stakeholders committed to maintaining or improving surface water quality in the stretch of the North Saskatchewan River from Devon to Pakan. Stakeholder and indigenous engagement on a Surface Water Quality Management Framework began in 2015 as a component of the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan, and continued in 2018. The current engagement will build on these initiatives and processes. Figure 1: The North Saskatchewan and Battle River Watersheds Surface Water Quality Pressures Surface Water Quality Status Rivers in the North Saskatchewan Region are relied upon for Many aspects of water quality in the North Saskatchewan source water for drinking, livestock watering, recreation, Region have improved in recent decades due to improved industry, providing healthy aquatic habitat and supporting management practices, especially wastewater treatment. traditional land use activities. However, pressure from Despite these advances, concerns for water quality in the different human activities can impact surface water quality in North Saskatchewan and Battle rivers include low dissolved the region. oxygen in the winter, nutrient enrichment, trace metals, and high sedimentation. Continuing efforts under the Water Population growth drives urban development, recreational Management Framework for the Industrial Heartland and growth, industrial growth and intensification of agricultural Capital Region are working to address these issues. -

The Methodists' Great 1869 Camp Meeting and Aboriginal Conservation Strategies in the North Saskatchewan River Valley

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 The Methodists' Great 1869 Camp Meeting and Aboriginal Conservation Strategies in The North Saskatchewan River Valley George Colpitts Department of the University of Calgary, in Alberta, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Colpitts, George, "The Methodists' Great 1869 Camp Meeting and Aboriginal Conservation Strategies in The North Saskatchewan River Valley" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1170. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1170 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE METHODISTS' GREAT 1869 CAMP MEETING AND ABORIGINAL CONSERVATION STRATEGIES IN THE NORTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER VALLEY GEORGE COLPITTS George McDougall, chairman of the Methodist gent of Wesleyan Methodists and their Native Missions to the Indians of the Northwest affiliates from Fort Edmonton, Pigeon Lake, Territories, kept a large, black book in which he Lac Ste. Anne, Lac La Biche, and Whitefish jotted sermon notes, references to classical and Lake-all located on the most northern and biblical literature and sometimes simply his itin westerly fringes of the northern Great Plains. eraries by horseback from Victoria, the primary Their expedition and other hunts joined by Methodist mission in the far British northwest. Protestant or Roman Catholic missions help Under the "s" tab and labeled "Saskatchewan," identify some of the strategies of competition he noted repeatedly in the 1860s the food crisis and cooperation emerging in the western boreal facing North Saskatchewan residents. -

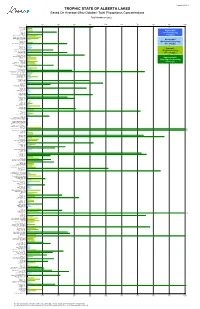

Trophic State of Alberta Lakes Based on Average Total Phosphorus

Created Feb 2013 TROPHIC STATE OF ALBERTA LAKES Based On Average (May-October) Total Phosphorus Concentrations Total Phosphorus (µg/L) 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 * Adamson Lake Alix Lake * Amisk Lake * Angling Lake Oligotrophic * ‡ Antler Lake Arm Lake (Low Productivity) * Astotin Lake (<10 µg/L) * ‡ Athabasca (Lake) - Off Delta Baptiste Lake - North Basin Baptiste Lake - South Basin * ‡ Bare Creek Res. Mesotrophic * ‡ Barrier Lake ‡ Battle Lake (Moderate Productivity) * † Battle River Res. (Forestburg) (10 - 35 µg/L) Beartrap Lake Beauvais Lake Beaver Lake * Bellevue Lake Eutrophic * † Big Lake - East Basin * † Big Lake - West Basin (High Productivity) * Blackfalds Lake (35 - 100 µg/L) * † Blackmud Lake * ‡ Blood Indian Res. Bluet (South Garnier Lake) ‡ Bonnie Lake Hypereutrophic † Borden Lake * ‡ Bourque Lake (Very High Productivity) ‡ Buck Lake (>100 µg/L) Buffalo Lake - Main Basin Buffalo Lake - Secondary Bay * † Buffalo Lake (By Boyle) † Burntstick Lake Calling Lake * † Capt Eyre Lake † Cardinal Lake * ‡ Carolside Res. - Berry Creek Res. † Chain Lakes Res. - North Basin † Chain Lakes Res.- South Basin Chestermere Lake * † Chickakoo Lake * † Chickenhill Lake * Chin Coulee Res. * Clairmont Lake Clear (Barns) Lake Clear Lake ‡ Coal Lake * ‡ Cold Lake - English Bay ‡ Cold Lake - West Side ‡ Cooking Lake † Cow Lake * Crawling Valley Res. Crimson Lake Crowsnest Lake * † Cutbank Lake Dillberry Lake * Driedmeat Lake ‡ Eagle Lake ‡ Elbow Lake Elkwater Lake Ethel Lake * Fawcett Lake * † Fickle Lake * † Figure Eight Lake * Fishing Lake * Flyingshot Lake * Fork Lake * ‡ Fox Lake Res. Frog Lake † Garner Lake Garnier Lake (North) * George Lake * † Ghost Res. - Inside Bay * † Ghost Res. - Inside Breakwater ‡ Ghost Res. - Near Cochrane * Gleniffer Lake (Dickson Res.) * † Glenmore Res. -

PP2 - Lakes, Reservoirs and Ponds Waterbody Waterbody Detail Season Bait WALL NRPK YLPR LKWH BURB Trout Total L = Bait Allowed Arm Lake OPEN MAY 15 to MAR

Legend: As examples, ‘3 over 63 cm’ indicates a possession and size limit of ‘3 fish each over 63 cm’ or ‘10 fish’ indicates a possession limit of 10 for that species of any size. An empty cell indicates the species is not likely present at that waterbody; however, if caught the default regulations for the Watershed Unit apply. SHL=Special Harvest Licence, BKTR = Brook Trout, BNTR=Brown Trout, BURB = Burbot, CISC = Cisco, CTTR = Cutthroat Trout, DLVR = Dolly Varden, GOLD = Goldeye, LKTR = Lake Trout, LKWH = Lake Whitefish, MNWH = Mountain Whitefish, NRPK = Northern Pike, RNTR = Rainbow Trout, SAUG = Sauger, TGTR = Tiger Trout, WALL = Walleye, YLPR = Yellow Perch. Regulation changes are highlighted blue. Waterbodies closed to angling are highlighted grey. PP2 - Lakes, Reservoirs and Ponds Waterbody Waterbody Detail Season Bait WALL NRPK YLPR LKWH BURB Trout Total l = Bait allowed Arm Lake OPEN MAY 15 TO MAR. 31 l 3 over 15 fish 63 cm Battle Lake Portion west of the west boundary of section 22-46-2-W5; OPEN JUNE 1 TO MAR. 31 l 0 fish 0 fish 5 fish 10 fish 2 fish; but limit Includes tributaries and outlet downstream to Sec. Rd. 771 is 0 from Feb. 1 to Mar. 31 Remainder of the lake OPEN MAY 15 TO MAR. 31 l 0 fish 0 fish 5 fish 10 fish 2 fish; but limit is 0 from Feb. 1 to Mar. 31 Berry Creek (Carolside) Reservoir 27-12-W4 OPEN MAY 15 TO MAR. 31 l 1 fish 45-50 1 fish 15 fish cm 63-70 cm Big Lake Includes tributaries OPEN MAY 15 TO MAR. -

Distribution, Abundance and Habitat Associations of Beavers, Muskrats, Mink and River Otters in the Aoserp Study Area, Northeastern Alberta

DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE AND HABITAT ASSOCIATIONS OF BEAVERS, MUSKRATS, MINK AND RIVER OTTERS IN THE AOSERP STUDY AREA, NORTHEASTERN ALBERTA by Gary F. Searing LGL LIMITED for ALBERTA OIL SANDS ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH PROGRAM Project LS 23.2 August 1979 ix TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION •••••••••...•.........•..•....•...••..•..•..... i i LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL~· .........••.....•.......•.......•.. iii DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY ••••................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ..................••........................ Xi i LIST OF FIGURES •....•.........•.....................•..... xi i i LIST OF AP~[NDICES ....................................... xiv ABSTRACT .•............•........•............ ~ ............. XV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................•.. xvi INTRODUCTION •............•................................ PART 1. HABITAT USE AND PREFERENCES OF BEAVERS, MUSKRATS, /MTNK AND RIVER OTTERS: A LITERATURE REVIEW . • . 4 l. INTRODUCTION •••..............••................ 4 2. BEAVER •.•....•••.............••...•.•....•..•.• 5 2.1 Introduction ....••.•.•.•...........•.........•. 5 2.2 Vegetative Requirements ....•..........•.•...... 8 2. 2.1 Food Quality •.•..................•..•....... 8 2.2.2 Food Quantity ...•...••....•...••••.•.••...•. 9 2.2.3 Distance Travelled for Food ............... .. 10 2.3 Lodge Site Requirements .•....•......•...•.•...• 11 2.4 Dam Site Requirements •••.•................••.•• 12 2.5 Canals ••••...•...••......••..••..•...•.•....... 12 2.6 Soil Requirements •..•.•....•....•..•••.••.•.••• -

Environmentally Significant Areas of Alberta Volume 2 Prepared By

Environmentally Significant Areas of Alberta Volume 2 Prepared by: Sweetgrass Consultants Ltd. Calgary, AB for: Resource Data Division Alberta Environmental Protection Edmonton, Alberta March 1997 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large portions of native habitats have been converted to other uses. Surface mining, oil and gas exploration, forestry, agricultural, industrial and urban developments will continue to put pressure on the native species and habitats. Clearing and fragmentation of natural habitats has been cited as a major area of concern with respect to management of natural systems. While there has been much attention to managing and protecting endangered species, a consensus is emerging that only a more broad-based ecosystem and landscape approach to preserving biological diversity will prevent species from becoming endangered in the first place. Environmentally Significant Areas (ESAs) are important, useful and often sensitive features of the landscape. As an integral component of sustainable development strategies, they provide long-term benefits to our society by maintaining ecological processes and by providing useful products. The identification and management of ESAs is a valuable addition to the traditional socio-economic factors which have largely determined land use planning in the past. The first ESA study done in Alberta was in 1983 for the Calgary Regional Planning Commission region. Numerous ESA studies were subsequently conducted through the late 1980s and early 1990s. ESA studies of the Parkland, Grassland, Canadian Shield, Foothills and Boreal Forest Natural Regions are now all completed while the Rocky Mountain Natural Region has been only partially completed. Four factors regarding the physical state of the site were considered when assessing the overall level of significance of each ESA: representativeness, diversity, naturalness, and ecological integrity. -

Battle River Synoptic Survey Phase II

Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. Battle River Synoptic Survey Phase II Prepared for: Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Job #: J130037 Contract: 140176 June, 2014 4482 97 St. NW, Edmonton, AB T6E 5R9 │ 587-773-4850 Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. 4482 97 Street, Edmonton, AB T6E 5R9 │ 587-773-4850 June 4, 2014 HESL Job #: J130037 Chris Teichreb Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development #304, 4920-51 St Red Deer, AB T4N 6K8 Dear Mr Teichreb: Re: Contract 140176 – Battle River Synoptic Survey Phase II – Draft Report Please find enclosed the final report describing the methods and results of the Phase II Battle River Synoptic Survey. We present the results in the context of Phase I Synoptic Survey results. We also provided an in-depth interpretation of temporal and spatial water quality trends in the Battle River using the collected lagoon and tributary data as well as land use information derived from GIS products. We also addressed your comments on the draft report and a detailed response is provided under separate cover by email. We thank you for the opportunity to assist AESRD with this project. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have any questions. Sincerely, Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. Dörte Köster, Ph.D., Senior Aquatic Scientist [email protected] R040614_J130037_Final_Report.docx J130037 , Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Battle River Synoptic Survey Phase II Signatures Report Prepared by: Christine Geiger, M.Sc. Dörte Köster, Ph.D. Aquatic Scientist Senior Aquatic Scientist Report Reviewed by: Deborah Sinclair, M.Sc. Senior Aquatic Scientist Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. R040614_J130037_Final_Report.docx ii J130037 , Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Battle River Synoptic Survey Phase II Executive Summary A set of draft WQOs for Battle River were developed for variables of concern in support of the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan (NSRP). -

Index Print Exit Index Print Exit Attractions

www.county.camrose.ab.ca Index Print Exit ALBERTA Edmonton www.county.camrose.ab.ca Index Print Exit Table of Contents Welcome to Camrose County 2 County Hamlets 37 Armena 37 Recreation 6 Duhamel 38 Golf 7 Kelsey 39 Gardening 9 Kingman 40 Bird Watching 10 Pelican Point 41 Exploring 11 Meeting Creek 42 Tillicum Park 12 Ohaton 43 Pelican Point Park 13 Round Hill 44 Campgrounds 14 Tillicum Beach 45 Bed and Breakfasts 16 Agriculture in Camrose County 46 Education 18 Commercial 48 Attractions 22 Contacting Camrose County 49 Health Care Services 24 County Map 50 Protective Services 25 History of Camrose County 26 county.camrose.ab.ca 27 Citys, Towns, and Villages 28 Camrose 28 Bashaw 30 Bawlf 31 Bittern Lake 32 Edberg 33 Ferintosh 34 Hay Lakes 34 New Norway 35 Rosalind 36 www.county.camrose.ab.ca Index Print Exit Welcome to Camrose County Camrose County is located in the east central region of Alberta, with its northwestern boundary located about 40 kilometres southeast of Edmonton when travelling on Highway 21. From this point, the County covers an area approximately 80 miles long from the north to south by 30 miles wide. Within this area there is about 837,093 acres of land classified as pasture, to very good arable soils throughout most of the district. This area is well known for its mixed farming attributes, as well as for its population of 7,160 people of mixed races originating from many different countries who live together in very harmonious and active communities. www.county.camrose.ab.ca Index Print Exit Within the boundaries of the County are, the City of Camrose, the Town of Bashaw and the Villages of Bittern Lake, Bawlf, Edberg, Ferintosh, Hay Lakes, New Norway and Rosalind as well as the hamlets of Armena, Duhamel, Kelsey, Kingman, Pelican Point, Meeting Creek, Ohaton, Round Hill and Tillicum. -

Bibliography on the Limnology and Fisheries of Canadian Freshwaters No .. 5 .. Fisheries and Arine Service Technical Report No

Bibliography on the limnology and fisheries of Canadian freshwaters No.. 5 .. by H. F. Nicholson. Great Lakes Biolimnology Laboratory, Canada Centre for Inland Waters, 867 Lakeshore Road, Burlington, Ontario. L7R 4A6 September 1978 Fisheries and arine Service Technical Report No.. 804 ·..a.. Fisheries and Environment Peches et Environnement l T Canada Canada Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et de Ia mer Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports These reports contain scientific and technical information that represents an important contribution to existing knowledge but which for some reason may not be appropriate for primary scientific (i.e. Journal) publication. Technical Reports are directed primarily towards a world wide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Fisheries and Marine Service, namely, fisheries management, technology and development, ocean sciences and aquatic environ ments relevant to Canada. Technical Reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report will be abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and will be indexed annually in the Service's index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Director ate Technical Reports. The series name was changed with report number 715. Details on the availability of Technical Reports in hard copy may be obtained from the issuing establishment indicated on the front cover. -

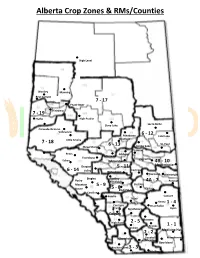

Alberta Crop Zones & Rms/Counties

Alberta Crop Zones & RMs/Counties High Level Worsley Manning Bear Canyon 7 - 17 Peace River Fairview 7 - 19 Hythe High Prairie Slave Lake Lac la Biche Grande Prairie Valleyview 6 - 12 Athabasca Cold Lake Westlock 7 - 18 Little Smoky 6 - 13 St. Paul Mayerthorpe Smoky Lake Lamont Peers Gibbons Onoway Evansburg Vegreville Edson Edmonton 4B - 10 Lloydminster Drayton 5 - 11 11 6 - 14 Valley Camrose Wetaskiwin Daysland Wainwright Bingley Rimbey Rocky Blackfalds 4A - 7 Provost Mountain 5 - 9 Stettler 5 - 8 Castor House Red Deer Caroline Sundre Consort Three Hills Hanna 1 - 4 Carstairs Drumheller 3 - 6 Strathmore Oyen Calgary Bassano High River 2 - 5 Brooks 1 - 1 Vulcan 2 - 2 Medicine Hat Claresholm Vauxhall Manyberries Lethbridge Bow Island Pincher Creek 3 - 3 Cardston Milk River Cities & Towns in Each Alberta Crop Zone 1 - 1 1 – 4 2 – 2 Pakowki Lucky Strike Aden Pashley Acadia Valley Albion Ridge Pendant Mallow Alderson Altario Allerston d'Oreille Masinasin Altorado Arneson Armelgra Pinhorn Matzhiwin Birdsholm Atlee Askow Pivot Maybutt Bow Island Benton Bantry Ralston McNab Bow River Benton Station Barnwell Ranchville Milk River Bowell Bindloss Barons Redcliff Millicent Bowmanton Buffalo Bassano Ronalane Monarch Bullshead Cavendish Bow City Rosebeg New Dayton Burdett Cereal Brooks Roytal Nobleford Cecil Cessford Broxburn Schuler Patricia Comrey Chinook Cassils Seven Persons Picture Butte Cressday Compeer Chin Skiff Piyami Dennis Consort Coaldale Stornham Princess Desert Blume Dorothy Coalhurst Suffield Purple Springs Dunmore Dowling Conrad Thelma Rainier Eagle Butte Drumheller Countess Tothill Raymond Etzikom Empress Coutts Vale Retlaw Florann Esther Craddock Veinerville Rolling Hills Foremost Excel Cranford Walsh Rosemary Gahern Finnegan Denhart Whitla Scandia Goddard Fleet Diamond City Wild Horse Shaughnessy Granlea Hanna Duchess Winnifred St. -

The Weather of the Canadian Prairies

PRAIRIE-E05 11/12/05 9:09 PM Page 3 TheThe WeWeatherather ofof TheThe CCanaanadiandian PrairiesPrairies GraphicGraphic AreaArea ForecastForecast 3232 PRAIRIE-E05 11/12/05 9:09 PM Page i TheThe WWeeatherather ofof TheThe Canadiananadian PrairiesPrairies GraphicGraphic AreaArea ForecastForecast 3322 by Glenn Vickers Sandra Buzza Dave Schmidt John Mullock PRAIRIE-E05 11/12/05 9:09 PM Page ii Copyright Copyright © 2001 NAV CANADA. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form, including photocopying or transmission electronically to any computer, without prior written consent of NAV CANADA. The information contained in this document is confidential and proprietary to NAV CANADA and may not be used or disclosed except as expressly authorized in writing by NAV CANADA. Trademarks Product names mentioned in this document may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies and are hereby acknowledged. Relief Maps Copyright © 2000. Government of Canada with permission from Natural Resources Canada Design and illustration by Ideas in Motion Kelowna, British Columbia ph: (250) 717-5937 [email protected] PRAIRIE-E05 11/12/05 9:09 PM Page iii LAKP-Prairies iii The Weather of the Prairies Graphic Area Forecast 32 Prairie Region Preface For NAV CANADA’s Flight Service Specialists (FSS), providing weather briefings to help pilots navigate through the day-to-day fluctuations in the weather is a critical role. While available weather products are becoming increasingly more sophisticated and, at the same time more easily understood, an understanding of local and region- al climatological patterns is essential to the effective performance of this role. -

Colonial Grebe Surveys in the Stony Plain Area

Western (Aechmophorus occidentalis) and Eared (Podiceps nigricollis) Grebes of Central Alberta: 2004 Field Summary A Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 94 Western (Aechmophorus occidentalis) and Eared (Podiceps nigricollis) Grebes of Central Alberta: 2004 Field Summary Gavin Berg Lisa Wilkinson Hugh Wollis And Dave Prescott Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 94 Publication No.: I/198 ISBN: 0-7785-3646-7 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-3647-5 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1496-7219 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (On-line Edition) Illustration: Stephen Hanus For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone (780) 422-2079 OR Visit our website at: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ This publication may be cited as: Berg, G., L. Wilkinson, H. Wollis, and D. Prescott. 2004. Western (Aechmophorus occidentalis) and Eared (Podiceps nigricollis) Grebes of Central Alberta: 2004 Field Summary. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 94. Edmonton, AB. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.....................................................................................................................................v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................................................................vi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................7