College Athletics Departments' Brand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appalachian State University

The University of North Carolina Capital Improvement Projects Report Required by S.L.2015-241 October 2017 - Quarterly Report Project Primary Funding Adequacy of Institution Program ID Project Name Source* Budget Commitments Status Constr. Completion Funding Appalachian State University [41230-308] - Steam Distribution and Steam and Condensate Upgrades Central Steam 41230-308 Condensate Lines 10479 Plant to Convocation Phase 1 Non-General $4,391,579 $4,361,838 Construction 06/03/2016 Adequate [41330-307] - Replacement of Steam System 41330-307 Condensate Line 12067 Stadium Lot Steam Manhole Repair Non-General $499,000 $33,900 Design Adequate Panhellenic Hall Fermentation Sciences 41530-301 Renovation 12367 Fermentation Science Relocation R&R General $1,025,000 $826,354 Construction 07/01/2016 Adequate [41430-304] - New Residence Hall - Winkler 41530-302 Replacement 12114 New Winkler Residence Hall Non-State Debt $32,000,000 $3,177,368 Design Adequate 41530-303 Howard Street Hall Renovation 12798 Howard Street Hall Renovation Non-General $2,657,905 $2,576,192 Construction 08/11/2017 Adequate 41530-304 Steam Plant Vault Utility Tunnel 14052 Steam Plant Vault Utility Tunnel Non-General $2,750,000 $226,571 Design Adequate 41530-305 Campus Master Plan Campus Master Plan Non-General $375,000 $0 Adequate Miles Annas Building Wellness Center 41530-306 Renovation 15481 Miles Annas Wellness Center Renovation Non-General $621,110 $596,670 Construction 11/18/2016 Adequate 41530-307 Doughton Hall Air Handler 14154 Doughton Make-up Air-Handler Replacement Non-General $440,669 $32,680 Construction Adequate 41530-308 2016 Carry-Forward 17256 Peacock Data Center Halon Replacement Non-General $175,000 $0 Adequate 41530-310 2016 Carry-Forward 17247 Chapel Wilson AC Replacement Non-General $105,000 $0 Adequate Physical Plant, Kerr Scott Hall, I.G. -

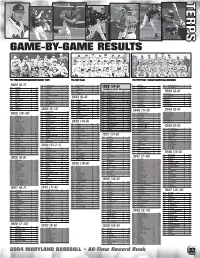

Game-By-Game Results

TERPS GAME-BY-GAME RESULTS The 1908 Maryland Agricultural College Team The 1925 Terps The 1936 Terps - Southern Conference Champions 1924 (5-7) 4-13 North Carolina L 9-12 5-1 Wake Forest W 8-7 4-15 Michigan L 0-6 5-8 Washington & Lee L 1-2 3-31 Vermont L 0-8 4-18 Richmond L 6-15 5-5 Duke L 4-7 1936 (14-6) 4-22 at Georgetown W 8-4 5-9 Georgetown L 1-9 4-9 Gallaudet W 13-1 4-30 NC State W 9-2 5-13 Richmond W 11-1 Southern Conf. Champions 4-25 Virginia Tech W 25-8 4-10 Marines W 8-1 5-3 Duke L 2-6 5-14 VMI W 9-5 3-26 Ohio State W 5-2 4-29 at Washington W 7-6 1943 (3-4) 4-17 Lehigh L 3-5 5-4 Virginia L 3-8 5-28 at Navy L 4-11 3-31 Cornell W 8-6 5-1 Duke W 9-8 at Fort Myers L 8-12 4-23 Georgia L 3-23 5-11 at Western Maryland W 4-2 4-1 Cornell L 6-7 5-3 William & Mary W 5-2 at Camp Holabird L 2-7 5-15 VMI L 5-6 4-24 Georgia L 8-9 1933 (6-4) 4-8 at Richmond L 0-2 5-5 Richmond W 8-5 Fort Belvoir W 18-16 5-16 at Navy W 7-4 4-25 West Virginia W 8-7 4-14 Penn State W 13-8 4-11 at VMI W 11-3 5-6 Washington W 5-2 at Navy JV W 13-4 5-1 NC State L 3-17 5-18 Washington & Lee W 6-5 4-17 at Duke L 0-8 4-18 Michigan W 14-13 5-16 Lafayette W 10-6 Fort Meade L 0-6 5-3 VMI L 7-11 5-18 Washington & Lee L 2-7 4-17 at Duke L 1-5 4-20 Richmond L 6-16 Greenbelt W 12-3 5-17 at Rutgers W 9-4 5-7 Washington W 7-1 5-19 at VMI W 2-1 4-18 at North Carolina L 0-8 4-23 Virginia L 3-4 at Fort Meade L 4-7 5-20 Georgetown W 4-0 5-14 Catholic W 8-0 4-19 Virginia L 6-11 4-25 at Georgetown L 2-5 5-20 at Virginia L 3-10 1929 (5-11) 5-9 at Washington & Lee W 4-0 4-28 West Virginia W 21-9 1944 (2-4) 4-3 Pennsylvania L 3-5 5-12 at VMI W 6-0 4-29 at Navy W 9-1 1940 (11-9) at Curtis Bay L 2-9 3-23 at North Carolina L 7-8 4-4 Cornell L 1-3 5-20 at Navy W 10-6 5-2 Georgetown W 12-9 Eng. -

Men's Lacrosse Looks to Get Back on Track After Losing Streak

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 14, 2021 128 YEARS OF SERVING UNC STUDENTS AND THE UNIVERSITY VOLUME 129, ISSUE 10 Last year, the Orange County public discussion and more since a group and run some candidates Board of Commissioners election their creation: for council and mayor, because Chapel was shaped by endorsements made we didn’t feel that the concerns by two local PACs. And in 2015, CHALT of the citizens were being heard,” 2017 and 2019, one local PAC found Henkel said. Hill’s many success in endorsing candidates for The Chapel Hill Alliance for In 2015, CHALT supported Pam Town Council. a Livable Town, or CHALT, is a Hemminger for mayor and three While some of these PACs focus group of community members who others for Town Council, including PACs, on fighting developments that don’t advocate for responsible growth Nancy Oates, Jessica Anderson and align with their vision for the town, and work to preserve Chapel Hill’s CHALT co-founder David Schwartz. others have focused on getting college-town character. Hemminger, Oates and Anderson explained funding for county schools. And The group was formed in 2014 were all elected. Chapel Hill isn’t alone — towns and in response to concerns that the In 2017, the organization formed Tom Henkel By Kayla Guilliams cities across the state have their own Town Council wasn’t listening to a PAC, the Chapel Hill Leadership Save Orange Schools Senior Writer local PACs that seek to influence community input on their Chapel Political Action Committee, to [email protected] local elections. Hill 2020 development plan, financially support its election-related Save Orange Schools and its Here are the PACs of Chapel Tom Henkel, one of the original activities. -

East Carolina Notes

INDIVIDUAL QUICK HITS EAST CAROLINA NOTES • Alec Burleson, who was named to five All-America teams in 2019, has earned inclusion on four teams ** 86th Season of Pirate Baseball (1932-42, 1946-2020) ** heading into his junior campaign ... Named presea- son AAC Player-of-the-Year accolades by leagues * 30 NCAA Regional Appearances / 16 of last 21 years * head coaches, Baseball America and D1Baseball ... Named to initial Golden Spikes Award and PROBABLE STARTERS Stopper-of-the-Year Watch List ... Owns an 13-5 Tuesday: ERA W-L APP GS CG SHO SV IP H R ER BB SO (72.2 win pct.) career record with nine saves in 47 ELON: Brian Edgington (RH) 7.00 0-0 5 0 0 0/0 0 9.0 14 8 7 5 10 appearances (21 starts) ... Can also play multiple ECU: Elijah Gill (LH) 7.36 0-1 3 1 0 0/1 0 3.2 7 3 3 0 5 positions (1B, RF, LF and DH) ... Sports a .342 career batting average with 11 home runs and 90 Wednesday: ERA W-L APP GS CG SHO SV IP H R ER BB SO RBI ... Named AAC Player-of-the-Week (3/9/20) ECU: TBA --- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- and to the AAC Honor Roll (2/24/20). UNCW: TBA --- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- • Tyler Smith has allowed four runs over 18.1 innings with 19 punch outs to 10 walks ... Owns an 18-3 career record (.857 win pct.) with one save and PIRATES ON THE AIR ... 2020 TEAM QUICK HITS 128 strikeouts in 196.2 innings (61 games/30 starts) ...................................................Pirate Sports Properties • ECU enters the week with a 12-3 record and has Radio: .. -

Development Plan Modification Concept Plan Application Letter From

UNlVERSITY ARCHITECT AND DIRECTOR FACILITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT ATTACHMENT 2 BOX NC March 15,2006 Ms. J.B. Culpepper Town of Chapel Hill Planning Office 306 North Columbia Street Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514 Re: Development Plan Modification 3- Concept Plan Dear Ms. Culpepper: Enclosed please find a Concept Plan Application for Development Plan Modification 3, as required by the 0I-4 zoning regulations. We have prepared plans showing previously approved projects, projects that have received Site Development Permits and the projects proposed as part of this modification. Also enclosed is a description of each project. We look forward to presenting this concept plan to the Council on April 19,2006. Please let me know if any additional information is required. Sincerely, Anna A. Wu, AIA Ms. Pat Crawford Ms. Mary Jane Felgenhauer Mr. Bruce Runberg Ms. Nancy Suttenfield March 15, 2006 CONCEPT PLAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFICATION 3 PROJECTS The Development Plan shows the buildings that the University and UNC Health Care System plan to build in the near future. The Town of Chapel Hill approved the University’s Development Plan in October 2001, Modification No. 1 in June and August 2003 and Modification No. 2 in March of 2004. The Development Plan Modification No. 3 will amend the location, size, and/or type of buildings and structures the University and the UNC Health Care System plan to construct under the Development Plan. The projects proposed in this Concept Plan are shown in Modification #3, Map 2, dated March 8, 2006. The accompanying list describes the scale and program use for each project. -

Westcovington Daviskirkpatrick

WESTCOVINGTON DAVISKIRKPATRICK Keith LeClair Head Coach (1997-2002) Introduction Player Profiles ������������������������������������������������32-55 Career Individual Pitching Records ������������������� 93 Schedule ���������������������������������������������������������������� 2 Pirates In the Community ����������������������������������56 Single-Season/Career Fielding Records ������������94 General Information & Quick Facts �����������������������3 Single-Game Records �����������������������������������������94 Media Guidelines������������������������������������������������4-5 2018 Opponents Freshman Hitting Records ����������������������������������95 Staff Directory �������������������������������������������������������6 2018 Opponents ���������������������������������������������58-64 Freshman Pitching Records ��������������������������������95 Primary Media Outlets �������������������������������������������7 Record Vs� All-Time Opponents ������������������������� 65 Miscellaneous Records ����������������������������������������96 Strength & Conditioning��������������������������������������� 8 Record Vs� The Conferences �������������������������66-68 Athletic Training ���������������������������������������������������� 8 History American Athletic Conference Pirate Notes ���������������������������������������������������������98 The University The American ������������������������������������������������������ 70 Coaching History ������������������������������������������99-100 2017 AAC Final Standings �������������������������������������71 -

Carolina Union Artwork Creates Community, Sense of Home

FEBRUARY 13, 2008 UNC HOME PAGE REDESIGN Until UNC’s main Web pages receive a makeover, the current site has been given a minor facelift. See story on page 2. CAROLINA’S FACULTY AND STAff NEWSPAPER ■ gazette.unc.edu Carolina Union artwork creates community, sense of home Downstairs, the Carolina Union bustles with activity. On a given day, thousands of students pass through to grab a cup of coffee, catch up with friends or hunker down in a comfortable chair tapping away on their laptops. Peeking out from the sea of tables and chairs are three of Clyde Jones’ “critters.” Commissioned in 2006, the wooden animal caricatures were constructed on site by the Chatham County artist and painted by Carolina students. As part of the union’s expanding art collection, these playful primitive sculptures help create the fun and warmth that can remind students of home. “It isn’t enough to supply coffee and tables. We want to create an inviting atmosphere here. Art is very important in creating that sense of community we’re after,” said Don Luse, Carolina Union director. For the past couple of years, Luse has been on a mission to fill the union with a variety of art, from oil paintings to pottery, quilts and brickwork to bronze and fiberglass sculptures — even glass doors depicting the beauty of a North Carolina sunset over the ocean. The union’s permanent art collection, named after Peggy Jablonski, vice chancellor for the building’s first two full-time directors, Howard student affairs, stands before “Thinking Henry and Archie Copeland, was started 10 years ago. -

UNC Integrated Water Management

3/28/2016 UNC Integrated Water Management 1 3/28/2016 Objectives… Provide overview of UNC’s Water Management Potable Water Non-Potable Water Lessons Learned Answer your questions How we got here UNC Campus Master Plan 2001 Environmental Master Plan 2002 Stormwater Management Plan 2004 Droughts of 2001-02 and 2007-08 Reclaimed Water Feasibility Study and Master Plan NC Water Regulations Jordan Lake Nutrient Rules 2 3/28/2016 UNC Environmental Master Plan 2002 1. Balance Growth with preservation of the natural drainage system. 2. Manage stormwater as an opportunity not as a problem. 3. Recognize that the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is part of the Cape Fear Watershed. 4. Reinforce the University’s position as a Role Model. UNC Stormwater Management Plan Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Best Management Practices (BMPs) Cisterns Green Roofs Infiltration Beds Porous Pavement Stream Daylighting 3 3/28/2016 Cisterns Hooker Field Rams Head Fed-Ex Global Education Bell Tower Project Genome Sciences Building Kenan Stadium Irrigation Marsico Hall Hanes Hall NC Botanical Gardens Hooker Field Cistern 4 3/28/2016 Rams Head Center Cistern Cistern and Green Roof Fed-Ex Global Education Cistern and Green Roof 5 3/28/2016 UNC Bell Tower Development Genome Science Building Central Park North Chiller Plant Bell Tower Non-Potable Water System Using roof andUNC groundwater Athletics from the cisternKenan with Reclaimed Stadium Water Makeup Genome Science Building ProposedCentral Park Roof Water New 330,000 -

2020 COASTAL CAROLINA BASEBALL SCHEDULE DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME (ET) BRITTAIN RESORTS BASEBALL at the BEACH Feb

2020 COASTAL CAROLINA BASEBALL SCHEDULE DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME (ET) BRITTAIN RESORTS BASEBALL AT THE BEACH Feb. 14 Virginia Tech vs. San Diego State Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. UNC GREENSBORO Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 4 P.M. Feb. 15 UNC Greensboro vs. Virginia Tech Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. SAN DIEGO STATE Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 3 P.M. Feb. 16 San Diego State vs. UNC Greensboro Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. VIRGINIA TECH Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 3 P.M. Feb. 18 at UNC Wilmington Wilmington, N.C. / Brooks Field 4 P.M. BRITTAIN RESORTS INVITATIONAL Feb. 21 Western Carolina vs. Illinois Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. Kennesaw State vs. West Virginia Myrtle Beach, S.C. / TicketReturn.com Field 1 P.M. SAINT JOSEPH’S Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 4 P.M. Feb. 22 Western Carolina vs. Kennesaw State Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. West Virginia vs. Saint Joseph’s Myrtle Beach, S.C. / TicketReturn.com Field 2 P.M. ILLINOIS Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 3 P.M. Feb. 23 Saint Joseph’s vs. Western Carolina Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 11 A.M. West Virginia vs. Illinois Myrtle Beach, S.C. / TicketReturn.com Field 11:30 A.M. KENNESAW STATE Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium 3 P.M. Feb. 24 WEST VIRGINIA Conway, S.C. / Springs Brooks Stadium NOON Feb. 26 at College of Charleston Charleston, S.C. -

Cornerstonefall 2019

Carolina CORNERSTONEFall 2019 In this Issue: Donor Spotlight: Claude and Sarah Snow, FORevHER Tar Heels Endowed Scholarship Dinner Reinforces Message of Opportunity Former Student-Athlete Spotlight: Bernadette McGlade, NCAA Trailblazer Donors with 50+ Years of Support Why We are Proud to Be Tar Heels - 2019 Spring Semester Academic Results Words from Associate Executive Director – Scholarship & Legacy Gifts Upcoming Dates to Remember Donor Spotlight SUE WALSH CLAUDE AND SARAH SNOW Associate Executive Director - FORevHER Tar Heels Scholarship and Legacy Gifts – 919.843.6413 Sarah and Claude Snow love the Tar Heels. And they love that, through their gifts, they can give a deserving young woman the chance to come to Carolina and compete. Recently, the – [email protected] a very generous deferred gift through their estate. Not only will their $2.6 million bequest Snows named The University of North Carolina and The Rams Club as the beneficiaries of benefit Carolina’s libraries and its School of Information and Library Science, but also the recently launched FORevHER Tar Heels women’s athletics initiative. in which Sarah and Claude have actively participated dating back to the Carolina Challenge CampaignLong-time insupporters the 1970s. of theNot University,only are the this Snows is the enthusiastic fifth consecutive about fundraisinggiving back, campaign but they love the University and all it has to offer, so much so that they moved to Chapel Hill from – Atlanta 20 years ago. “We were coming here four to five times a year, not counting football and basketball,” Sarah said. “We kind of laughed and said, ‘Why are we doing this? Let’s just RAMSCLUB.COM move to Chapel Hill.’ And here we are.” Endowed Scholarship Dinner Claude and Sarah began supporting Carolina Athletics nearly four decades ago and have generously given REINFORCES MESSAGE OF OPPORTUNITY to numerous initiatives including: the renovation well. -

RFP for In-Venue Merchandise Sales

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Title: UNC Department of Athletics Carolina Athletics In-Venue Merchandise Provider Issuer: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Attn: Alexis Barlow Ernie Williamson Athletics Center, CB 8500 450 Skipper Bowles Drive Chapel Hill, NC 27514 RFP Issue Date: Friday, February, 23, 2018 Response Deadline: Monday, April 2, 2018 Important: Four (4) hard copies of the proposal and one (1) electronic copy on a CD or USB drive are to be submitted to the issuing agency at the address indicated above. Sealed proposals will be received until 5:00 p.m. on April 2, 2018, for furnishing services as described herein, at the address indicated above as the issuing agency. Proposals not received by 5:00 p.m. on April 2, 2018, shall not be considered. Postmarks will not be considered in judging the timeliness of submissions. Proposals submitted by fax will not be accepted. A pre-proposal conference will be held on Monday, March 5th at 1:00 pm in the in the first floor conference room in the Ernie Williamson Athletic Center, which is adjacent to the Dean Smith Center (parking is available in the lot behind EWAC, with an access code that will be emailed to the attending parties). The pre-proposal conference will begin with a presentation of the RFP, include a questions and answers session, and conclude with a tour of the Athletic Facilities to include in- venue merchandise sales areas. Attendance at the pre-proposal conference by all interested companies is strongly encouraged by the issuing agency. Please notify UNC via email at ([email protected]) of your intention to attend the conference and include the names and titles of those representing your firm. -

Wake Forest Baseball 1955, 1962, 1963, 1977, 1998, 1999, 2001 ACC Champions

wake forest baseball 1955, 1962, 1963, 1977, 1998, 1999, 2001 ACC Champions Non-Conference Opponents Winthrop Western Kentucky Davidson Home: April 19 Neutral: February 12 Home: February 15 Away: Feb. 10, Feb. 13 Away: April 6 University Information University Information University Information Location Rock Hill, SC Location Bowling Green, KY Location Davidson, NC Enrollment 6,610 Enrollment 18,350 Enrollment 1,700 Baseball Information Baseball Information Baseball Information Head Coach Joe Hudak Head Coach Joel Murrie Head Coach Dick Cooke Record at School 451-313-5 (13) Record at School 794-619 (25) Record at School 272-436-1 (14) 2004 Record 37-23 2004 Record 35-28 2004 Record 20-33 38 Last Meeting March 7, 2004 (Won 4-2) Last Meeting First ever meeting Last Meeting March 23, 2004 (Lost 11-9) Series History (Streak) Tied, 1-1 (Won 1) Series History (Streak) N/A Series History (Streak) WFU leads 28-10 (Lost 1) wake forest Media Information Media Information Media Information baseball Baseball Contact John Verser Baseball Contact Chris Glowacki Baseball Contact Rick Bender coaching Phone Number (803) 366-0647 Phone Number (270) 745-5388 Phone Number (704) 894-2123 Fax Number (803) 323-2433 Fax Number (270) 745-3444 Fax Number (704) 996-4668 staff E-Mail [email protected] E-Mail [email protected] E-Mail [email protected] Pressbox Phone (803) 323-2155 Pressbox Phone (270) 745-6941 Pressbox Phone (704) 894-2740 2005 demon deacons South Alabama Jacksonville Texas A&M 2005 Neutral: February 18 Neutral: February 19 Neutral: February