Journal of Arts & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION 1 Using this book 2 Visiting the SouthWestern United States 3 Equipment and special hazards GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 4 Visiting Grand Canyon National Park 5 Walking in Grand Canyon National Park 6 Grand Canyon National Park: South Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails South Bass Trail Hermit Trail Bright Angel Trail South Kaibab Trail Grandview Trail New Hance Trail Tanner Trail 7 Grand Canyon National Park: North Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails Thunder River and Bill Hall Trails, with Deer Creek Extension North Bass Trail North Kaibab Trail Nankoweap Trail 8 Grand Canyon National Park: trans-canyon trails, North and South Rim Table of Trails Escalante Route: Tanner Canyon to New Hance Trail at Red Canyon Tonto Trail: New Hance Trail at Red Canyon to Hance Creek Tonto Trail: Hance Creek to Cottonwood Creek Tonto Trail: Cottonwood Creek to South Kaibab Trail Tonto Trail: South Kaibab Trail to Indian Garden Tonto Trail: Indian Garden to Hermit Creek Tonto Trail: Hermit Creek to Boucher Creek Tonto Trail: Boucher Creek to Bass Canyon Clear Creek Trail 9 Grand Canyon National Park: South and North Rim trails South Rim Trails Rim Trail Shoshone Point Trail North Rim Trails Cape Royal Trail Cliff Springs Trail Cape Final Trail Ken Patrick Trail Bright Angel Point Trail Transept Trail Widforss Trail Uncle Jim Trail 10 Grand Canyon National Park: long-distance routes Table of Routes Boucher Trail to Hermit Trail Loop Hermit Trail to Bright Angel Trail Loop Cross-canyon: North Kaibab Trail to Bright Angel Trail South -

Tanner to the Little Colorado River

Tanner to the Little Colorado River Natural History Backpack April 3-9, 2020 with Melissa Giovanni CLASS INFORMATION AND SYLLABUS DAY 1 Meet at 10:00 a.m. at the historic Community This class focuses on the geology, anthropology, Building in Grand Canyon Village (Google Map). ecology, and history of eastern Grand Canyon. We will orient ourselves to the trip and learn some This route is unique among South Rim hikes due basic concepts of geology as well. We will first to the stunning exposures of most of the major spend some time on introductions and gear, food, rock groups that compose the walls of Grand and the class. After lunch we will have a short Canyon. While we will not be able to view the session in the classroom and then go out to the deepest and innermost crystalline and rim (and perhaps partway down one of the major metamorphic rocks, we will see exposures of the trails) to become familiar with regional geography younger Precambrian strata unequaled anywhere and landmarks. We will also cover fundamental else. geology tenets that lay the ground work for the rest of the class, including: The class also provides superb views of underlying structural features, including faults, A geographic overview of the region unconformities, and intrusions not visible The three rock families; how they form and elsewhere. We will see one of the most profound how this is reflected in their appearance faults in Grand Canyon, one that may have played The principles of stratigraphy a major role in the formation of the canyon itself. -

The M a G a Z I

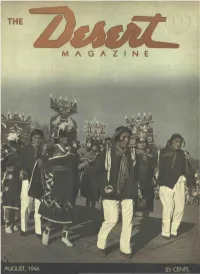

THE MAGAZINE AUGUST, 1946 25 CENTS ill Pliotol One of the most thrilling of the outdoor sports on the desert is rock climbing, and in order to give Desert Magazine readers a glimpse of this form of adventure, the August photo prizes will be awarded for rock climb- ing pictures. Photos should show climbing action, tech- i nics, or any phase of the sport. WBEgmmm Noiina in Blaam Winner of first prize in Desert Magazine's June "Desert in Blossom" contest is this photo of a Noiina in bloom in Joshua Tree national monument, by L. B. Dixon, Del Mar, California. Taken with a Leica, 50mm objective, Plus X film, developed in DK20. Exposure 1/60 f6.3 with Aero No. 2 filter, straight print on F2 Kodabromide. SlnUa Hubert A. Lowman, Southgate, California, won sec- ond prize with his view of a Night-blooming Sinita, or Whisker cactus. Photo taken in Organ Pipe Cactus na- tional monument, Arizona, with flash exposure. Photos of merit were purchased for future use in Desert Magazine from the following contestants: Claire Meyer Proctor, Phoenix, Arizona; C. H. Lord, Los Angeles, and Hubert A. Lowman. DESERT • Next scory by Randall Henderson will be about Ed. Williams of Blythe, Cali- fornia, who since 1912 has handled many tough problems for his neighbors in Palo Verde valley, from his million-dollar er- rand to Washington through the fight for an equitable division of irrigation water from the Colorado river. • New name among DESERT'S writers is that of Ken Stott Jr., curator of mam- Volume 9 AUGUST, 1946 Number 10 mals, Zoological Society of San Diego, whose initial story will be an account of night collecting of desert reptiles. -

Historical Development of Water Resources at the Grand Canyon

Guide Feb 7-8, 2015 Training Pioneer Trails Seminar “to” Grand Canyon by Dick Brown Grand Canyon Historical Society Pioneers of the Grand Canyon Seth B. Tanner* Niles J. Cameron* Louis D. Boucher* William F. Hull* Peter D. Berry* Babbitt Brothers John Hance* John A. Marshall Ellsworth Kolb William W. Bass* William O. O’Neill Emery Kolb William H. Ashurst Daniel L. Hogan* Charles J. Jones* Ralph H. Cameron* Sanford H. Rowe James T. Owens* * Canyon Guides By one means or another, and by a myriad of overland pathways, these pioneers eventually found their way to this magnificent canyon. Seth Benjamin Tanner Trailblazer & Prospector . Born in 1828, Bolton Landing, on Lake George in Adirondack Mountains, NY . Family joined Mormon westward migration . Kirtland, OH in 1834; Far West, MO in 1838; IL in 1839; IA in 1840 . Family settled in "the promised land" near Great Salt Lake in 1847 . Goldfields near Sacramento, CA in 1850 . Ranching in San Bernardino, CA (1851-1858) . Married Charlotte Levi, 1858, Pine Valley, UT, seven children, Charlotte died in 1872 . Led Mormon scouting party in 1875, Kanab to Little Colorado River . Married Anna Jensen, 1876, Salt Lake City, settled near today’s Cameron Trading Post . In 1880, organized Little Colorado Mining District and built Tanner Trail . Later years, Seth (then blind) & Annie lived in Taylor, 30 miles south of Holbrook, AZ Photo Courtesy of John Tanner Family Association . Seth died in 1918 William Francis Hull Sheep Rancher & Road Builder . Four brothers: William (born in 1865), Phillip, Joseph & Frank . Hull family came from CA & homesteaded Hull Cabin near Challender, southeast of Williams . -

Wes Hildreth

Transcription: Grand Canyon Historical Society Interviewee: Wes Hildreth (WH), Jack Fulton (JF), Nancy Brown (NB), Diane Fulton (DF), Judy Fierstein (JYF), Gail Mahood (GM), Roger Brown (NB), Unknown (U?) Interviewer: Tom Martin (TM) Subject: With Nancy providing logistical support, Wes and Jack recount their thru-hike from Supai to the Hopi Salt Trail in 1968. Date of Interview: July 30, 2016 Method of Interview: At the home of Nancy and Roger Brown Transcriber: Anonymous Date of Transcription: March 9, 2020 Transcription Reviewers: Sue Priest, Tom Martin Keys: Grand Canyon thru-hike, Park Service, Edward Abbey, Apache Point route, Colin Fletcher, Harvey Butchart, Royal Arch, Jim Bailey TM: Today is July 30th, 2016. We're at the home of Nancy and Roger Brown in Livermore, California. This is an oral history interview, part of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Oral History Program. My name is Tom Martin. In the living room here, in this wonderful house on a hill that Roger and Nancy have, are Wes Hildreth and Gail Mahood, Jack and Diane Fulton, Judy Fierstein. I think what we'll do is we'll start with Nancy, we'll go around the room. If you can state your name, spell it out for me, and we'll just run around the room. NB: I'm Nancy Brown. RB: Yeah. Roger Brown. JF: Jack Fulton. WH: Wes Hildreth. GM: Gail Mahood. DF: Diane Fulton. JYF: Judy Fierstein. TM: Thank you. This interview is fascinating for a couple different things for the people in this room in that Nancy assisted Wes and Jack on a hike in Grand Canyon in 1968 from Supai to the Little Colorado River. -

Searching for the Hopi Center of Creation

searching for the hopi center of creation arizonahighways.com APRIL 2003 SacredSacred Vistas Vistas Navajo ofof thethe going up Young Rock Climbers Face Their Fears Verde ValleyRiver Paradise Paradise a bounty of birds Hassayampa A Peaceful Waterfront Retreat Rattlesnake Grease and Cockroach Tea frontier medicine APRIL 2003 COVER/PORTFOLIO 20 Magnificent Navajoland page 50 The stories and glorious beauty of this vast terrain tell of a proud Indian heritage. 55 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP Arizona’s state mammal — the ringtail, or cacomistle — was a favorite pet of lonely old miners. ADVENTURE 6 Rugged Hike to Sipapu 44 HUMOR It’s no easy trek to Blue Spring and the 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL sacred Hopi site called Sipapu on the Little Colorado River. 46 DESTINATION Hassayampa River Preserve The beautiful variety of natural wonders might 36 HISTORY even have appealed to artist Claude Monet. Medicine on 3 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP Arizona’s Frontier Explore Arizona oddities, attractions and pleasures. Territorial physicians were mostly brave U.S. 54 EXPERIENCE ARIZONA Army surgeons doubling as naturalists, A birding and nature festival flies into Yuma; the bookkeepers, weathermen and gardeners. world’s largest outdoor Easter pageant unfolds in Mesa; Miami celebrates its mining history; and Arizona 40 TRAVEL commemorates its Asian pioneers in Phoenix. Finding Courage in the Rocks 49 ALONG THE WAY Young climbers triumph over their fears as they What’s really behind a place name? It’s not always challenge the cliffs of Queen Creek Canyon. what you’d think. 50 BACK ROAD ADVENTURE BIRDS Ruby Road to Buenos Aires 14 National Wildlife Refuge Flocking to Verde Valley Woodlands, small lakes, grasslands and a chance The birds know it’s all about ideal location in to see wildlife mark this 50-mile drive. -

Tanner Trail

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Tanner Trail The lower reaches of the Grand Canyon below Desert View are dominated by a series of tilted layers of stone known as the Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Supergroup is a complex collection of ancient sedimentary and igneous rocks ranging in age from 800 million to 1.2 billion years, the oldest sedimentary deposits in the canyon. The colorful rocks are soft and easily eroded so the canyon floor is unusually expansive, offering unimpeded views of some of the steepest walls to be found below the rim. In addition to being geologically noteworthy, the Tanner Trail is also historically significant. Native people used this natural rim-to-river route for several thousand years and the trail as we know it today has been in constant use since 1890 (when it was improved by Franklin French and Seth Tanner). The Tanner Trail allowed early miners access to their claims and was used as the southern component of the disreputable Horsethief Route. Wilderness seekers are only the latest humans to discover the charms of the area. The historic Tanner Trail is the primary access by foot into the eastern Grand Canyon. The trail is unmaintained and ranks as one of the most difficult and demanding south side trails, but for an experienced canyon walker the aesthetic bounty of the area will be adequate compensation. Locations/Elevations Mileage Lipan Point (7350 ft / 2240 m) to Colorado River (2700 ft / 823 m): 9 mi (14.4 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Desert View Quad (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) Sky Terrain Trails Map, Grand Canyon (Sky Terrain) Water Sources The Colorado River is the sole source of water. -

Commercial Backpacking/Day Hiking/Transit Official Use Only 2

Form 10-115 Rev. 11/15/2016 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park Park Contact: Permits Coordinator, [email protected] Phone Number: 928-638-7707 COMMERCIAL USE AUTHORIZATION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF P.L. 105-391 Section 418, (54 U.S.C. 101925) 1. AUTHORIZED ACTIVITY: Permit Number: CUA GRCA 5600 ____ Commercial Backpacking/Day Hiking/Transit Official Use Only 2. Authorization Holder Information Authorization: Begins:_______________ (Type information below) Official Use Only CONTACT NAME (Owner or Authorized Agent) Authorization Expires: December 31, 2020 ORGANIZATION/COMPANY EMAIL ADDRESS MAILING ADDRESS US DOT # CITY;STATE;ZIP TELEPHONE NUMBER/ FAX NUMBER 3. The holder is hereby authorized to use the following described land or facilities in the above named area (area must be restored to its original condition at the end of the authorization): Areas within Grand Canyon National Park open to the general public as designated by the attached authorization conditions. 4. Summary of authorized activity: (see attached sheets for additional information and conditions) Commercial guided backpacking, day hiking, and associated transit within Grand Canyon National Park. ☒ Out- of- Park: The commercial services described above must originate and terminate outside of the boundaries of the park area. This permit does not authorize the holder to advertise, solicit business, collect fees, or sell any goods or services within the boundaries of the park area. ☐In-Park: The commercial service described above must originate and be provided solely within the boundaries of the park area 5. NEPA/NHPA Compliance: Internal Use Only ☐Categorical Exclusion ☐ EA/FONSI ☐ EIS ☐ Other Approved Plans 6. -

Hiker Perception of Wilderness in Grand Canyon National Park: a Study of Social Carrying Capacity

Hiker perception of wilderness in Grand Canyon National Park: a study of social carrying capacity Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Towler, William L. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 01:56:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566421 HIKER PERCEPTION OF WILDERNESS IN GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK: A STUDY OF SOCIAL CARRYING CAPACITY by William Leonard Towler A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AND URBAN PLANNING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN GEOGRAPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 7 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

Grand Canyon National Park: Tanner and Beamer Trails to Little Colorado River | Backpacking in Arizona

Grand Canyon National Park: Tanner and Beamer Trails to Little Colorado River | Backpacking in Arizona NATIONAL PARKS QUICKLINKS -select- SUBSCRIBE | NEWSLETTERS | MAPS | VIDEOS | BLOGS | MARKETPLACE | CONTESTS Grand Canyon National Park: Tanner and Beamer Trails to Little Colorado River This stout three-day backpacking trip emphasizes the "grand" in Grand Canyon as it follows hardscrabble trails to remote campsites, old mining claims, and the scene of an airplane crash. Ter Map Sat Hyb Ter MyTopo OSM OCM MS Map Tanner Trail (26 photos) MS Sat MS Hyb 1 of 1 Map data ©2012 Google - Terms of Use MAP TOOLS Author: Backpacker Magazine Activity: Backpacking Elevation Profile State: Arizona (AZ) Distance: 37 mi SHARE TRIP Difficulty: 7 / 10 USGS Topo Map: Desert View, Cape Solitude Social Bookmarks Rating: 2 rating(s) Like more bookmarks... Here's the deal: This 37-mile trip, connecting the Tanner and Beamer Trails to the Little Colorado River, is for seasoned, fit hikers with solid navigation skills. If that's CREATE A TRIP you, read on. If not, amp up your adventure resume with other Grand Canyon hikes before trying this challenging trek to beachside campsites, a plane crash site, and All Gear Preplan Trip & Map 100-year-old mining ruins. Upload .gpx File To start, drop off the South Rim from Lipan Point on the Tanner Trail. It's a 4,600- Download From foot, knee-buckling descent to the Colorado River over 9 miles, your first water Garmin source on this three- to four-day trek. Pack enough water for five hours of descending and consider dropping a water cache at Seventy-five mile saddle or the Guide To Using GPS top of the Redwall for your ascent back to the rim. -

Ethnographic Resources in the Grand Canyon Region

Interim Report Ethnographic Resources in the Grand Canyon Region Prepared by Saul Hedquist and T. J. Ferguson School of Anthropology University of Arizona Prepared for Jan Balsom Grand Canyon National Park Task Agreement Number J8219091297 Cooperative Agreement Number H1200090005 May 30, 2010 Table of Contents 1. Research Objectives .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Study Area .................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Ethnographic Resources Inventory Database ............................................................................. 3 4. Ethnographic Resources Inventory GIS Project ......................................................................... 4 5. Geographical Distribution of Ethnographic Resources in the Vicinity of the Grand Canyon ... 6 Aboriginal Lands as Ethnographic Resources ............................................................................ 7 Ethnographic Resources Associated with the Proposed North Parcel Withdrawal Area ........... 9 Ethnographic Resources Associated with the Proposed East Parcel Withdrawal Area ........... 11 Ethnographic Resources Associated with the Proposed South Kaibab Withdrawal Area ....... 13 Ethnographic Resources within Grand Canyon National Park ................................................. 15 6. Tribal Distribution of Ethnographic Resources .......................................................................