Harvey Butchart's Hiking Log Introduction and Early Protologs To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Centennial and a Great Opportunity

CanyonVIEWS Volume XXIII, No. 4 DECEMBER 2016 Interview with Superintendent Chris Lehnertz Celebrating 100 Years: National Park Service Centennial An Endangered Species Recovers The official nonprofit partner of Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Association Canyon Views is published by the Grand Canyon Association, the National Park Service’s official nonprofit partner, raising private funds to benefit Grand Canyon National Park, operating retail stores and visitor centers within the park and providing premier educational opportunities about the natural and cultural history of Grand Canyon. FROM THE CEO You can make a difference at Grand Canyon! Memberships start at $35 annually. For more What a year it’s been! We celebrated the 100th anniversary information about GCA or to become a member, of the National Park Service, and together we kicked off critically please visit www.grandcanyon.org. important conservation, restoration and education programs here at Board of Directors: Stephen Watson, Board the Grand Canyon. Thank you! Chair; Howard Weiner, Board Vice Chair; Lyle Balenquah; Kathryn Campana; Larry Clark; Sally Clayton; Richard Foudy; Eric Fraint; As we look forward into the next 100 years of the National Park Robert Hostetler; Julie Klapstein; Kenneth Service at Grand Canyon National Park, we welcome a new partner, Lamm; Robert Lufrano; Mark Schiavoni; Marsha Superintendent Chris Lehnertz. This issue features an interview with Sitterley; T. Paul Thomas the park’s new leader. I think you will find her as inspirational as we Chief Executive Officer: Susan Schroeder all do. We look forward to celebrating Grand Canyon National Park’s Chief Philanthropy Officer: Ann Scheflen Centennial in 2019 together! Director of Marketing: Miriam Robbins Edited by Faith Marcovecchio We also want to celebrate you, our members. -

Boatman's Quarterly Review

boatman’s quarterly review fall 2002 the journal of volume 15 number 3 Grand Canyon River Guides, Inc Changing of Guard Prez Blurb Dear Eddy Harvey Butchart Jan Yost Back of the Boat Things to Remember Letter from G.C. Books CRMP From the Trenches Wilderness, Motors… Intrepid Lizard Suturing Where Did the Dirt Go? Ballot Comments Financials Contributors boatman’s quarterly review Changing of the Guard …is published more or less quarterly by and for Grand Canyon River Guides. ICHARD QUARTAROLi has been manning the helm Grand Canyon River Guides of gcrg (appropriate boating metaphor!) for the is a nonprofit organization dedicated to Rpast year. His contributions have been signifi- cant—from conducting a myriad of meetings (board Protecting Grand Canyon meetings, fall meeting, gts, crmp planning meetings, Setting the highest standards for the river profession you name it!), to constantly being involved with the Celebrating the unique spirit of the river community important issues at hand. His vision of an Old Timer’s Providing the best possible river experience Guides Training Seminar came to fruition with one of the best-attended sessions ever. And his involvement General Meetings are held each Spring and Fall. from start to finish was crucial to its success—from Our Board of Directors Meetings are generally held assisting with the Arizona Humanities Council grant, to the first Wednesday of each month. All innocent the lengthy planning process, and even serving as emcee bystanders are urged to attend. Call for details. of the event. It has been a supreme pleasure working with someone so committed to Grand Canyon in every Staff way, and so knowledgeable about its history. -

Mountaineer December 2011

The Arizona Mountaineer December 2011 ORC students and instructors Day 3 - McDowell Mountains Photo by John Keedy The Arizona Mountaineering Club Meetings: The member meeting location is: BOARD OF DIRECTORS Granite Reef Senior Center President Bill Fallon 602-996-9790 1700 North Granite Reef Road Vice-President John Gray 480-363-3248 Scottsdale, Arizona 85257 Secretary Kim McClintic 480-213-2629 The meeting time is 7:00 to 9:00 PM. Treasurer Curtis Stone 602-370-0786 Check Calendar for date. Director-2 Eric Evans 602-218-3060 Director-2 Steve Crane 480-812-5447 Board Meetings: Board meetings are open to all members Director-1 Gretchen Hawkins 520-907-2916 and are held two Mondays prior to the Club meeting. Director-1 Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 Director-1 Jutta Ulrich 602-738-9064 Dues: Dues cover January through December. A single membership is $30.00 per year: $35.00 for a family. COMMITTEES Those joining after June 30 pay $15 or $18. Members Archivist Jef Sloat 602-316-1899 joining after October 31 who pay for a full year will have Classification Nancy Birdwell 602-770-8326 dues credited through the end of the following year. Dues Elections John Keedy 623-412-1452 must be sent to: Equip. Rental Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 AMC Membership Committee Email Curtis Stone 602-370-0786 6519 W. Aire Libre Ave. Land Advocacy Erik Filsinger 480-314-1089 Glendale, AZ 85306 Co-Chair John Keedy 623-412-1452 Librarian David McClintic 602-885-5194 Schools: The AMC conducts several rock climbing, Membership Rogil Schroeter 623-512-8465 mountaineering and other outdoor skills schools each Mountaineering Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 year. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION 1 Using this book 2 Visiting the SouthWestern United States 3 Equipment and special hazards GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 4 Visiting Grand Canyon National Park 5 Walking in Grand Canyon National Park 6 Grand Canyon National Park: South Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails South Bass Trail Hermit Trail Bright Angel Trail South Kaibab Trail Grandview Trail New Hance Trail Tanner Trail 7 Grand Canyon National Park: North Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails Thunder River and Bill Hall Trails, with Deer Creek Extension North Bass Trail North Kaibab Trail Nankoweap Trail 8 Grand Canyon National Park: trans-canyon trails, North and South Rim Table of Trails Escalante Route: Tanner Canyon to New Hance Trail at Red Canyon Tonto Trail: New Hance Trail at Red Canyon to Hance Creek Tonto Trail: Hance Creek to Cottonwood Creek Tonto Trail: Cottonwood Creek to South Kaibab Trail Tonto Trail: South Kaibab Trail to Indian Garden Tonto Trail: Indian Garden to Hermit Creek Tonto Trail: Hermit Creek to Boucher Creek Tonto Trail: Boucher Creek to Bass Canyon Clear Creek Trail 9 Grand Canyon National Park: South and North Rim trails South Rim Trails Rim Trail Shoshone Point Trail North Rim Trails Cape Royal Trail Cliff Springs Trail Cape Final Trail Ken Patrick Trail Bright Angel Point Trail Transept Trail Widforss Trail Uncle Jim Trail 10 Grand Canyon National Park: long-distance routes Table of Routes Boucher Trail to Hermit Trail Loop Hermit Trail to Bright Angel Trail Loop Cross-canyon: North Kaibab Trail to Bright Angel Trail South -

Grand Canyon National Park U.S

National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper North Rim 2015 Season The Guide North Rim Information and Maps Roosevelt Point, named for President Theodore Roosevelt who in 1908, declared Grand Canyon a national monument. Grand Canyon was later established as a national park in 1919 by President Woodrow Wilson. Welcome to Grand Canyon S ITTING ATOP THE K AIBAB a meadow, a mother turkey leading her thunderstorms, comes and goes all too flies from the South Rim, the North Plateau, 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400– young across the road, or a mountain quickly, only to give way to the colors Rim offers a very different visitor 2,750 m) above sea level with lush lion slinking off into the cover of the of fall. With the yellows and oranges of experience. Solitude, awe-inspiring green meadows surrounded by a mixed forest. Visitors in the spring may see quaking aspen and the reds of Rocky views, a slower pace, and the feeling of conifer forest sprinkled with white- remnants of winter in disappearing Mountain maple, the forest seems to going back in time are only a few of the barked aspen, the North Rim is an oasis snowdrifts or temporary mountain glow. Crispness in the air warns of winter many attributes the North Rim has in the desert. Here you may observe lakes of melted snow. The summer, snowstorms soon to come. Although to offer. Discover the uniqueness of deer feeding, a coyote chasing mice in with colorful wildflowers and intense only 10 miles (16 km) as the raven Grand Canyon’s North Rim. -

Tanner to the Little Colorado River

Tanner to the Little Colorado River Natural History Backpack April 3-9, 2020 with Melissa Giovanni CLASS INFORMATION AND SYLLABUS DAY 1 Meet at 10:00 a.m. at the historic Community This class focuses on the geology, anthropology, Building in Grand Canyon Village (Google Map). ecology, and history of eastern Grand Canyon. We will orient ourselves to the trip and learn some This route is unique among South Rim hikes due basic concepts of geology as well. We will first to the stunning exposures of most of the major spend some time on introductions and gear, food, rock groups that compose the walls of Grand and the class. After lunch we will have a short Canyon. While we will not be able to view the session in the classroom and then go out to the deepest and innermost crystalline and rim (and perhaps partway down one of the major metamorphic rocks, we will see exposures of the trails) to become familiar with regional geography younger Precambrian strata unequaled anywhere and landmarks. We will also cover fundamental else. geology tenets that lay the ground work for the rest of the class, including: The class also provides superb views of underlying structural features, including faults, A geographic overview of the region unconformities, and intrusions not visible The three rock families; how they form and elsewhere. We will see one of the most profound how this is reflected in their appearance faults in Grand Canyon, one that may have played The principles of stratigraphy a major role in the formation of the canyon itself. -

Trip Planner Grand Canyon U.S

Grand Canyon National Park National Park Service Trip Planner Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Table of Contents 2 General Information 3 Getting to Grand Canyon 4 Weather 5-6 South Rim 7–8 North Rim 9–10 Tours and Trips 11 Hiking Map 12 Day Hiking 13 Hiking Tips 14–15 Backpacking 16 Get Involved 17 Sustainability 18 Beyond The Rims 19 Park Partners Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around the word or website indicates a website or link. Trip Planner1 1 Table of contents Grand Canyon National Park Trip Planner Welcome to Grand Canyon Where is it? Park Passes Grand Canyon is in the northwest corner of Admission to the park is $25 per private ve- Arizona, close to the borders of Utah and hicle; $12 per pedestrian or cyclist. The pass Nevada. The Colorado River, which flows can be used for seven days and includes both through the canyon, drains water from seven rims. Single vehicle park passes may be pur- states, but the feature we know as Grand chased outside the park’s south entrance in Canyon is entirely in Arizona. Tusayan, Arizona at: Grand Hotel GPS Coordinates Grand Canyon Squire Inn Canyon Plaza Resort North Rim Visitor Center Red Feather Lodge 36°11’51”N 112°03’09”W RP Stage Stop South Rim Visitor Center Xanterra Trading Post 36°03’32”N 112°06’33”W Imax—National Park Service Desk Grand Canyon Flight—at the Grand Desertview Watchtower Canyon Airport 36° 2’ 38” N 111° 49’ 33”W An $80 Annual Pass provides entrance into all national parks and federal recreational lands for one year. -

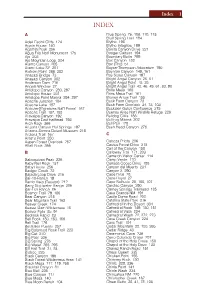

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

PRELIMINARY REPORT of INVESTIGATIONS of SPRINGS in the MOGOLLON RIM REGION, ARIZONA By

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey PRELIMINARY REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS OF SPRINGS IN THE MOGOLLON RIM REGION, ARIZONA By J. H. Feth With sections on: Base flow of streams By N. D. White and Quality of water By J. D. Hem Open-file report. Not reviewed for conformance with editorial standards of the Geological Survey. Tucson, Arizona June 1954 CONTENTS Page Abstract ................................................... 1 Introduction................................................. 3 Purpose and scope of investigation.......................... 3 Location and extent of area ................................ 4 Previous investigations.................................... 5 Personnel and acknowledgments ............................ 5 Geography .................................................. 6 Land forms and physiographic history ...................... 6 Drainage ................................................ 6 Climate ................................................. 6 Development and industry.................................. 8 Minerals"................................................. 9 Water ................................................... 9 Geology .................................................... 10 Stratigraphy ............................................. 10 Rocks of pre-Mesozoic age ............................. 10 Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks .................... 10 Tertiary and Quaternary sedimentary rocks .............. 11 Lake beds .......................................... 11 San Carlos basin -

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004 Jeff and I left the Fruita-4 place at about 8 AM and tooled west on I-70 to exit 202 at UT-128 near Cisco, Utah. We drove south on UT-128 through the Colorado River canyons to US-191, just north of Moab. We turned south and drove through Moab on US-191 to US-163, past Bluff, Utah. US-163 veers southwest through Monument Valley into Arizona and the little town of Keyenta. At Keyenta we took US-160 west to US-89, then south to AZ-64. We drove west past the fairly spectacular canyons of the Little Colorado River and into the east entrance to Grand Canyon National Park. Jeff had a Parks Pass so we saved $20 and got in for free. Entry included the park information paper, The Guide, which included a park map that was especially detailed around the main tourist center: Grand Canyon Village. Near the village was our pre-hike destination, the Backcountry Office. We stopped at the office and got an update on the required shuttle to the trailhead. We read in The Guide that mule rides into the canyon would not begin until May 23, after we were done with our hike. Satisfied that we had the situation under control we skeedaddled on outta there on US-180, south to I-40 and Williams, Arizona. Jeff had tried his cell phone quite a few times on the trip from Fruita, but no signal. Finally the signal was strong enough in Williams. Jeff noted that Kent had called and returned the call.