Grand Canyon National Park to America’S Considered in This Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Canyon Getaway September 23-26, 2019 $1641.00

Golden Opportunity Grand Canyon Getaway September 23-26, 2019 $1641.00 (Double) $1985.00 (Single) Accepting Deposits (3-00.00) (Cash, credit card or check) $300.00 2nd Payment Due May 3, 2019 $300.00 3rd Payment Due June 7, 2019 $300.00 4th Payment Due July 5, 2 019 Balance due August 2, 2019 The Grand Canyon is 277 river miles long, up to 18 miles wide, and an average depth of one mile. Over 1,500 plant, 355 bird, 89 mammalian, 47 reptile, 9 amphibian, and 17 fish species. A part of the Colorado River basin that has taken over 40 million years to develop. Rock layers showcasing nearly two billion years of the Earth’s geological history. Truly, the Grand Canyon is one of the most spectacular and biggest sites on Earth. We will board our flight at New Orleans International Airport and fly into Flagstaff, AR., where we will take a shuttle to the Grand Canyon Railway Hotel in Williams, AR to spend our first night. The hotel, w hich is located adjacent to the historic Williams Depot, is walking distance to downtown Williams and its famed main street – Route 66. The hotel features rooms updated in 2015 and 2016 with an indoor swimming pool and a hot tub. Williams, AR. Is a classic mountain town located in the Ponderosa Pine forest at around 6,800 feet elevation. The town has a four-season climate and provides year-round activities, from rodeos to skiing. Dubbed the “Gateway to the Grand Canyon”, Williams Main Street is none other than the Mother Road herself – Route 66. -

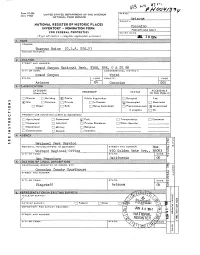

""65CODE COUNTY: M Arizona Coconino 003 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) to the PUBLIC

Form 10-306 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arizona NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Coconino INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) 101974 Tasayan Ruins (G.L.A. 22Q..g) STREET AND NUMBER: Grand Canyon National Park, T30N, R5E, G .& SR CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Grand Canyon Third ""65CODE COUNTY: m Arizona Coconino 003 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District rj] Building Public Public Acquisition: I 1 Occupied Yes: S' te L7] Structure Private [""'] In Process Q Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object Both [~~1 Being Considered |~1 Preservation work [^ Unrestricted in progress a NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Q Agricultural Q Government £P Park Transportation I ] Comments Q Commercial Q] Industrial [~1 Private Residence Other (-Specify; Q Educational | | Military [~~| Religious [~~1 Entertainment | | Museum [~"1 Scientific National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: BOX .Westerfl ..Regional" Of flee_r U50 Golden Gate Are., 36063 CITY OR TOWN: ii^PMiiii^^i^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: _____Goconino County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Flagstaff TI/TLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: NATIONAL REGISTER CITY OR TOWN: (Check One) Excellent Good QFair Deteriorated Ruins [~1 Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One; Altered Unaltered Moved (]£] Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Preservation recommended This pueblo was_originj^l.y "_U-s^ It was built~e»f^^ T^eguarly-shaped boulders ? la id in^clayjnortar. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION 1 Using this book 2 Visiting the SouthWestern United States 3 Equipment and special hazards GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 4 Visiting Grand Canyon National Park 5 Walking in Grand Canyon National Park 6 Grand Canyon National Park: South Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails South Bass Trail Hermit Trail Bright Angel Trail South Kaibab Trail Grandview Trail New Hance Trail Tanner Trail 7 Grand Canyon National Park: North Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails Thunder River and Bill Hall Trails, with Deer Creek Extension North Bass Trail North Kaibab Trail Nankoweap Trail 8 Grand Canyon National Park: trans-canyon trails, North and South Rim Table of Trails Escalante Route: Tanner Canyon to New Hance Trail at Red Canyon Tonto Trail: New Hance Trail at Red Canyon to Hance Creek Tonto Trail: Hance Creek to Cottonwood Creek Tonto Trail: Cottonwood Creek to South Kaibab Trail Tonto Trail: South Kaibab Trail to Indian Garden Tonto Trail: Indian Garden to Hermit Creek Tonto Trail: Hermit Creek to Boucher Creek Tonto Trail: Boucher Creek to Bass Canyon Clear Creek Trail 9 Grand Canyon National Park: South and North Rim trails South Rim Trails Rim Trail Shoshone Point Trail North Rim Trails Cape Royal Trail Cliff Springs Trail Cape Final Trail Ken Patrick Trail Bright Angel Point Trail Transept Trail Widforss Trail Uncle Jim Trail 10 Grand Canyon National Park: long-distance routes Table of Routes Boucher Trail to Hermit Trail Loop Hermit Trail to Bright Angel Trail Loop Cross-canyon: North Kaibab Trail to Bright Angel Trail South -

Grand Canyon National Park U.S

National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper North Rim 2015 Season The Guide North Rim Information and Maps Roosevelt Point, named for President Theodore Roosevelt who in 1908, declared Grand Canyon a national monument. Grand Canyon was later established as a national park in 1919 by President Woodrow Wilson. Welcome to Grand Canyon S ITTING ATOP THE K AIBAB a meadow, a mother turkey leading her thunderstorms, comes and goes all too flies from the South Rim, the North Plateau, 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400– young across the road, or a mountain quickly, only to give way to the colors Rim offers a very different visitor 2,750 m) above sea level with lush lion slinking off into the cover of the of fall. With the yellows and oranges of experience. Solitude, awe-inspiring green meadows surrounded by a mixed forest. Visitors in the spring may see quaking aspen and the reds of Rocky views, a slower pace, and the feeling of conifer forest sprinkled with white- remnants of winter in disappearing Mountain maple, the forest seems to going back in time are only a few of the barked aspen, the North Rim is an oasis snowdrifts or temporary mountain glow. Crispness in the air warns of winter many attributes the North Rim has in the desert. Here you may observe lakes of melted snow. The summer, snowstorms soon to come. Although to offer. Discover the uniqueness of deer feeding, a coyote chasing mice in with colorful wildflowers and intense only 10 miles (16 km) as the raven Grand Canyon’s North Rim. -

An Architectural Walk Around the South

An Architectural Walk Around the South Rim Oscar Berninghaus, A Showery Day Grand Canyon, 1915 El Tovar, 1905 Power House, 1926 Hopi House, 1905 Hermit's Rest, 1914 Lookout Studio (The Lookout), 1914 Desert View Watchtower, 1932 Bright Angel Lodge, 1936 Charles Whittlesey, El Tovar, 1905 Charles Whittlesey, El Tovar, 1905 Charles Whittlesey, El Tovar, 1905 Dreams of mountains, as in their sleep they brood on things eternal Daniel Hull (?), Powerhouse, 1926 Daniel Hull (?), Powerhouse, 1926 Daniel Hull (?), Powerhouse, 1926 Mary Jane Colter, Indian Building, Albuquerque, 1902 Mary Jane Colter, Hopi House, 1905 Walpi, c. 900 CE Interior of Home at Oraibi Mary Jane Colter, Hopi House, 1905 Mary Jane Colter, Hopi House, Nampeyo and Lesou, 1905 Mary Jane Colter, Hopi House, 1905 Mary Jane Colter, Hopi House, 1905 Mary Jane Colter, Hermit’s Rest ,1914 The Folly, Mount Edgcumbe, Cornwall, c. 1747 Sargent's Folly, Franklin Park, Boston, 1840 Mary Jane Colter, Hermit’s Rest ,1914 Mary Jane Colter, Hermit’s Rest ,1914 Mary Jane Colter, Lookout Studio, (The Lookout), 1914 Mary Jane Colter, Lookout Studio, (The Lookout), 1914 Mary Jane Colter, Lookout Studio, (The Lookout), 1914 Mary Jane Colter, Lookout Studio, (The Lookout), 1914 Frank Lloyd Wright, Kaufmann House, Bear Run, PA , 1935 Mary Jane Colter, Lookout Studio, (The Lookout), 1914 Mary Jane Colter, Desert View Watchtower, 1934 Square Tower, Hovenweep Round Tower, Hovenweep Round Tower, Cliff Palace Mary Jane Colter, Desert View Watchtower, 1934 Mary Jane Colter, Desert View Watchtower, 1934 Casa Rinconada Kiva, c. 1,200 CE Casa Rinconada Kiva, c. 1,200 CE Mary Jane Colter, Desert View Watchtower, 1934 Pueblo Bonito, c. -

Arizona, Road Trips Are As Much About the Journey As They Are the Destination

Travel options that enable social distancing are more popular than ever. We’ve designated 2021 as the Year of the Road Trip so those who are ready to travel can start planning. In Arizona, road trips are as much about the journey as they are the destination. No matter where you go, you’re sure to spy sprawling expanses of nature and stunning panoramic views. We’re looking forward to sharing great itineraries that cover the whole state. From small-town streets to the unique landscapes of our parks, these road trips are designed with Grand Canyon National Park socially-distanced fun in mind. For visitor guidance due to COVID19 such as mask-wearing, a list of tourism-related re- openings or closures, and a link to public health guidelines, click here: https://www.visitarizona. com/covid-19/. Some attractions are open year-round and some are open seasonally or move to seasonal hours. To ensure the places you want to see are open on your travel dates, please check their website for hours of operation. Prickly Pear Cactus ARIZONA RESOURCES We provide complete travel information about destinations in Arizona. We offer our official state traveler’s guide, maps, images, familiarization trip assistance, itinerary suggestions and planning assistance along with lists of tour guides plus connections to ARIZONA lodging properties and other information at traveltrade.visitarizona.com Horseshoe Bend ARIZONA OFFICE OF TOURISM 100 N. 7th Ave., Suite 400, Phoenix, AZ 85007 | www.visitarizona.com Jessica Mitchell, Senior Travel Industry Marketing Manager | T: 602-364-4157 | E: [email protected] TRANSPORTATION From east to west both Interstate 40 and Interstate 10 cross the state. -

Linen, Section 2, G to Indians

Arizona, Linen Radio Cards Post Card Collection Section 2—G to Indians-Apache By Al Ring LINEN ERA (1930-1945 (1960?) New American printing processes allowed printing on postcards with a high rag content. This was a marked improvement over the “White Border” postcard. The rag content also gave these postcards a textured “feel”. They were also cheaper to produce and allowed the use of bright dyes for image coloring. They proved to be extremely popular with roadside establishments seeking cheap advertising. Linen postcards document every step along the way of the building of America’s highway infra-structure. Most notable among the early linen publishers was the firm of Curt Teich. The majority of linen postcard production ended around 1939 with the advent of the color “chrome” postcard. However, a few linen firms (mainly southern) published until well into the late 50s. Real photo publishers of black & white images continued to have success. Faster reproducing equipment and lowering costs led to an explosion of real photo mass produced postcards. Once again a war interfered with the postcard industry (WWII). During the war, shortages and a need for military personnel forced many postcard companies to reprint older views WHEN printing material was available. Photos at 43%. Arizona, Linen Index Section 1: A to Z Agua Caliente Roosevelt/Dam/Lake Ajo Route 66 Animals Sabino Canyon Apache Trail Safford Arizona Salt River Ash Fork San Francisco Benson San Xavier Bisbee Scottsdale Canyon De Chelly Sedona/Oak Creek Canyon Canyon Diablo Seligman -

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers Our first holiday in the USA was a relaxed trip with about equal time spent on mammalwatching, birding and hiking, but often all three could be combined. Mammal highlights included White-nosed Coati, Hooded Skunk, Striped Skunk, American Badger and unfortunately brief views of Black-footed Ferret. There were many birding highlights but I was particularly pleased with sightings of Montezuma Quail, Scaled Quail, Red-faced Warbler, Elegant Trogon, Greater Roadrunner, Elf Owl, Spotted Owl, Dusky Grouse and Californian Condor. American Badger Introduction Arizona seemed to offer a good introduction to both the avian and mammalian delights of North America. Our initial plan was to do a comprehensive two-week visit of southeast Arizona, but after some back and forth we decided to include a visit to the Grand Canyon, also because this allowed a visit to Seligman for Badger and Black-footed Ferret and Vermillion Cliffs for Californian Condor. Overall, the schedule worked out pretty well, even if the second part included a lot more driving, although most of the driving was through pleasant or even superb scenery. I was already a little skeptical of including Sedona before the trip, and while I don’t regret having visited the Sedona area, from a mammal and birding perspective it is a destination that could be excluded. Another night in Seligman and more hiking/birding around Flagstaff would probably have been more productive. 1 Timing and Weather By late May/early June the northbound migratory species have largely left southeast Arizona so you mainly get to see the resident birds and summer visitors. -

Grand Canyon West?

The Insider’s Guide to the Grand Canyon: Spring 2007 Helping You Get the Most Out of Your Grand Canyon Vacation! Thank you for choosing Grand Canyon.com as your Southwestern vacation specialist! You’ve not only chosen an extraordinary place for your vacation, but you’ve also picked a great time to visit. Having lived and worked in the Grand Canyon area for over 20 years, our staff has made a few observations and picked up a few “insider tips” that can help save you time, money and hassle - sometimes all three at once! If you’ve gotten most of your Grand Canyon vacation planned by now - booked your flights, reserved your rental car, secured hotel rooms, mapped your itinerary, etc. – then take your left hand, put it on your right shoulder, and pat yourself on the back! You get to skip to Travel Tip #8. For those who‘ve just now decided on the Grand Canyon for your spring break vacation, we hope you’ll find this guide helpful in putting together a trip you’ll be smiling about for years to come! Before you dig in, we recommend that you have a few minutes of quiet time, a map or road atlas, a pen and/or a highlighter, maybe a beverage, and your “Grand Canyon Top Tours Brochure.” Let’s get started and get YOU to the Grand Canyon! 1 Travel Tip 1 – Where Is the Grand Canyon? Grand Canyon National Park is in Northern Arizona. Travel Tip 2 – What Side Can I See it From? Grand Canyon South Rim and Grand Canyon West (a.k.a. -

Of Our Favorite Things

TALON AGENTS: THE MAJESTIC ARTIST ROBERT SHIELDS: AUGUST 1909: WILDLIFE ECOLOGY BIRDS OF CAVE CREEK CANYON NOPE. HE’S NOT ALL MIME IS BORN IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS AUGUST 2009 ESCAPE. EXPLORE. EXPERIENCE BEST ofAZ of our favorite things 100featuring BRANDON WEBB & ROGER CLYNE plus DIERKS BENTLEY: The Coolest Dude in Country Music and A Pulitzer Winner and a Camera Went Into the Catalinas … contents 08.09 features 14 BEST OF AZ Our first-ever guide to the best of everything in Arizona, from eco-friendly accommodations to secret hide- aways and margaritas. The latter, by the way, come courtesy of Roger Clyne, the Tempe-based rock star. Cy Young Award-winner Brandon Webb pitched in on this piece as well, and so did NFL referee Ed Hochuli. Grand Canyon Some of the choices you’ll agree with. Others, prob - National Park ably not. Either way, this is our take on the “Best of Flagstaff Arizona.” EDITED BY KELLY KRAMER Sedona Springerville 36 A PULITZER WINNER AND A Camp Verde Globe CAMERA WENT INTO THE CATALINAS ... PHOENIX It sounds like a joke, doesn’t it? It’s not. We just wrote departments that to get your attention. When it comes to photography, 2 EDITOR’S LETTER 3 CONTRIBUTORS 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Santa Catalina Jack Dykinga is dead serious. That’s why he has a Pulitzer Mountains sitting on his mantel. Or maybe it’s shoved in a drawer — 5 THE JOURNAL www.arizonahighways.com People, places and things from around the state, that’s more Jack’s style. -

Civilian Conservation Corps

The 2. Bright Angel Trailhead 3. Transcanyon Telephone Line 4. A Rock Wall with Heart building. Colter Hall has served as housing for Civilian Conservation Corps Ascend the stairway and walk to the right (west), Reverse your direction and walk east back along the Walk east along the rim to between Kachina Lodge single women concession employees since it was built in the 1930s. Did a c c c boy carve the stone A Legacy Preserved at Grand Canyon Village following the rim a few hundred feet to the stone- rim. Descend the c c c steps and continue past Kolb and El Tovar Hotel. Look for the heart-shaped and-pipe mule corral. Studio, Lookout Studio, and Bright Angel Lodge. stone in the guard wall. heart and place it in the wall as a symbol to his Look for the bronze plaque on the stone wall. beloved in Colter Hall? Or is this just an inter- Severe economic depression projects that would benefit the country. Early American Indians used the route followed by the Civilian Conservation Corps crews completely esting natural rock? No one knows. 1933 challenged the confidence of the in its existence, however, the program added Bright Angel Trail long before the first pioneers Because communication between the North rebuilt the rock wall along the rim from people of the United States. One in four people was emphasis to teach “the boys” skills and trades. arrived in the 1880s. Walk 800 feet (250 m) down and South Rims was frequently difficult and Verkamps Curios to Lookout While the c c c crews were unemployed.