Titling Homes As Real Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

A Guide to Conservation Easements for the Real Estate Industry

A Guide to Conservation Easements for the Real Estate Industry Berkeley County Farmland Protection Board February 2021 Berkeley County Farmland Protection Board PO Box 1243, Martinsburg, WV 25402 (mail) 229 E. Martin Street, Suite 3, Martinsburg WV 25401 (office) (304) 260-3770 Email: [email protected] Web: Berkeley.wvfp.org About this Guide This document explores the basics of conservation easements, including many of the restrictions an easement places on real property. The intended audience is real estate professionals and lawyers who oversee land sales. Because conservation easements can be complex, involve multiple parties with perpetual interests in the land, and frequently interact with US income tax law, this guide can only provide an overview of an easement. It is strongly recommended that parties involved in the sale or purchase of a conservation easement first contact the Berkeley County Farmland Protection Board for specific information about the easement. Please note that this document does not provide specific legal or tax advice. Vested parties should always seek legal and financial advice from a qualified professional. Contents What is a Conservation Easement? ............................................................................................................... 1 What are the Financial Implications? ............................................................................................................ 3 What Are the Property Owner’s Rights? ..................................................................................................... -

Business Personal Property

FAQs Business Personal Property What is a rendition for Business Personal Property? A rendition is simply a form that provides the District with the description, location, cost, and acquisition dates for personal property that you own. The District uses the information to help estimate the market value of your property for taxation purposes. Who must file a rendition? Renditions must be filed by: Owners of tangible personal property that is used for the production of income Owners of tangible personal property on which an exemption has been cancelled or denied What types of property must be rendered? Business owners are required by State law to render personal property that is used in a business or used to produce income. This property includes furniture and fixtures, equipment, machinery, computers, inventory held for sale or rental, raw materials, finished goods, and work in progress. You are not required to render intangible personal property (property that can be owned but does not have a physical form) such as cash, accounts receivable, goodwill, application computer software, and other similar items. If your organization has previously qualified for an exemption that applies to personal property, for example, a religious or charitable organization exemption, you are not required to render the exempt property. When and where must the rendition be filed? The last day to file your rendition is April 15 annually. If you mail your rendition, it must be postmarked by the U. S. Postal Service on or before April 15. Your rendition must be filed at the appraisal district office in the county in which the business is located, unless the personal property has situs in a different county. -

EMINENT DOMAIN PROCESS STATE of NEW JERSEY Anthony F. Della Pelle, Esq

EMINENT DOMAIN PROCESS STATE OF NEW JERSEY Anthony F. Della Pelle, Esq. CRE McKirdy & Riskin, P.A. 136 South Street, PO Box 2379 Morristown, New Jersey 07960 973-539-8900│www.mckirdyriskin.com www.njcondemnationlaw.com [email protected] Who is Eligible to Condemn? Power Generally The State is vested with the power of eminent domain as an attribute of sovereignty. The exercise of the power is within the exclusive province of the legislative branch of government. The Legislature may delegate the power to others. The New Jersey Constitution provides for delegation of the power and provides for the nature of the estates or interests which may be acquired under the power. N.J. Const. Art. 1, Sec. 20; N.J. Const. Art. 4, Sec. 6, par. 3. The authority to acquire private property for redevelopment of blighted areas is the subject of a specific constitutional provision. N.J.S.A. Const. Art. 8, § 3, ¶ 1. The provisions of the Constitution and of any law concerning municipal corporations formed for local government, or concerning counties, shall be liberally construed in their favor. N.J.S.A. Const. Art. 4, § 7, ¶ 11. The Legislature has delegated the power of eminent domain to a broad range of sub- agencies and public bodies and public utilities too numerous for listing. Public utilities are generally provided with the power of eminent domain pursuant to N.J.S.A.48:3-17.6. What Can Be Condemned All types of property, real and personal, tangible and intangible, are subject to the power of eminent domain provided a valid public purpose exists for the proposed use of such property. -

Residential Real Estate Conveyancing

BEST PRACTICE MANUAL Residential Real Estate Conveyancing The material is this manual is for illustration purposes only and is not to be copied or shared. Some of the information is compiled from the following sources: Continuing Legal Education Society Law Society of British Columbia of British Columbia Practical Legal Training Course Conveyancing Deskbook Real Estate Practice Manual The Society strongly recommends that its members subscribe to the CLE course materials noted above. ENCOURAGING BEST PRACTICE FOR BC NOTARIES 1 April 2009 Index RESIDENTIAL REAL Estate CONVEYANCING ................................................... 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................4 Relying on Staff.............................................................................................................5 Talking to your Client .....................................................................................................5 Taking Instructions ........................................................................................................6 Scope of the Retainer ...................................................................................................7 Multiple Clients .............................................................................................................8 Consent/Conflict of Interest ..........................................................................................8 Independent Legal Advice ..........................................................................................11 -

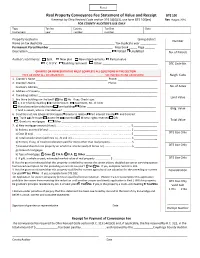

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Accounting Considerations Relating to Developers of Condominium Projects

St. John's Law Review Volume 48 Number 4 Volume 48, May 1974, Number 4 Article 11 Accounting Considerations Relating to Developers of Condominium Projects Michael A. Conway Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCOUNTING CONSIDERATIONS RELATING TO DEVELOPERS OF CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS MICHAEL A. CONWAY* INTRODUCTION Interest in the concept of condominium ownership in the United States has been rapidly increasing in recent years. This article discusses accounting considerations relating to profit recognition by developers and sellers of condominium projects. It also touches briefly on the historical development of the condominium concept, some of the distinctions between condominiums and cooperatives, and the dif- ferences between fee and leasehold condominiums. While the discus- sions in this article are directed primarily towards condominiums, many of the principles involved are also applicable to cooperatives. References made to legal requirements are for illustrative purposes and should not be construed as providing guidance on legal matters. CONCEPT A condominium is a form of ownership that contemplates more than a casual relationship with other owners. An individual is deeded his own homestead along with an undivided interest in common areas and facilities which are jointly controlled with other owners. Common areas may include swimming pools, sauna baths, golf courses, and other amenities. -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Real Estate Law for Planners

Real Estate Law for Planners APA National Conference New York, NY May 9, 2017 Your Panelists Brian Connolly Otten Johnson Robinson Neff + Ragonetti, P.C. Denver, Colorado Evan Seeman Robinson & Cole LLP Hartford, Connecticut Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 2 Your Panelists David Silverman Ancel Glink Chicago, Illinois Brian Smith Robinson & Cole LLP Hartford, Connecticut Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 3 Session Outline • Parties to the real estate transaction • Basics of real property law – Possessory interests – Non-possessory interests – Conveyancing • Title issues • Government interests in real property • Panel discussion – Role of planning and zoning in real estate transactions – The planner’s role in real estate transactions Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 4 Things to Remember • Planners have important roles in real estate transactions—whether you know it or not • Basic overview • Real estate law is state-by-state law: use this presentation with caution! • Always consult attorneys when real estate transactions are involved Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 5 PARTIES TO THE REAL ESTATE TRANSACTION Parties to Real Estate Transaction • Buyer-Seller • Broker • Lenders • Title Company • Surveyors • Lawyers Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 7 Role of the Planner • How are planners involved? 1. A savvy broker/owner may seek to determine the “highest and best” use of the property to maximize development potential and financial return 2. Zone changes, text amendments to zoning regulations, and subdivisions may be needed *We will return to “highest and best” use later Real Estate Law for Planners / May 9, 2017 8 Role of the Planner (continued) • Buyer’s Due Diligence 1. -

Purchase Price Allocation in Real Estate Transactions

PURCHASE PRICE ALLOCATION IN REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS: Does A + B + C Always Equal Value? Morris A. Ellison, Esq. 1 Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, LLP Nancy L. Haggerty, Esq. Michael Best & Friedrich, LLP Purchasers of income-generating real estate generally focus solely on cash flow rather than the individual components generating that cash flow. This seeming truism has not been true either for larger transactions involving substantial personal property or goodwill or in the context of ad valorem taxation where taxing authorities generate separate tax bills, often at different rates, for real property, personal property and business licensing fees. This proposition is becoming less true in the current economic environment, as lenders face increasing regulatory pressure to “take less risk” by separately valuing the components generating the income and valuing the risk separately. Originating primarily in the context of valuing hotel properties for proper determination of the project’s real estate value for ad valorem tax purposes, the concept of component analysis has far broader applications. The Appraisal Institute 2 currently includes as potential additional candidates for component analysis: (i) health care facilities such as hospitals, nursing homes and ambulatory surgical centers; (ii) regional shopping centers, office buildings and apartments; (iii) restaurants and nightclubs; (iv) recreational facilities such as theme parks, theaters, sports venues and golf courses; and (v) manufacturing firms. 3 The purpose of this paper is not to present a study of component analysis bur rather to identify some of the areas where component analysis should be considered. The Concept of Component Analysis Investors typically look primarily at total cash flow without attributing cash flow to specific components. -

Resale Certificate from Condominium Association - 2018

REALTORS® ASSOCIATION OF NEW MEXICO RESALE CERTIFICATE FROM CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION - 2018 Don Grosvenor ("Seller") requests that the Deseo HOA Association furnish the following information no later than , in accordance with the New Mexico Condominium Act with respect to the following property: 7A Unit Building Percentage Ownership in Common Areas 209 Los Pandos, Unit 7A Taos NM Address City Zip Code Legal Description or see metes and bounds description attached as Exhibit, County, New Mexico. New Mexico law requires disclosure of all of the matters listed below for every resale of a residential condominium which is not exempt from the Condominium Act. (Exempt transactions include: gifts, sales under court orders, sale by government agency, foreclosure or deed in lieu of foreclosure, sale to person in business of selling real estate for purpose of resale, sale that is cancelable by the buyer at any time without penalty.) 1. Any right of first refusal or other restraint on free transferability of the Unit is described below: 2. The current common expense assessment is $ per month quarter year other and the unpaid common expense or special assessment currently due and payable from Seller is $ (Under New Mexico law, a buyer is not liable for any unpaid fee or assessment greater than the amount set forth by the Association in this certificate.) 3. Other fees payable by Unit owners are: 4. Capital expenditures anticipated by the Association for the current and next two fiscal years are: $ 5. The reserves for capital expenditures and any portion of those reserves designated for specified projects are: $ 6. The most recently prepared balance sheet and income and expense statements of the Association, if any, are attached.