Negotiating the Integration Strategies and the Transnational Statuses Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devani Approved Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: [2020] EWCA Civ 612 Case No: C5/2019/1038 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) Deputy Upper Tribunal Judge Latter Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 07/05/2020 Before: LORD JUSTICE UNDERHILL (Vice-President of the Court of Appeal (Civil Division)) LADY JUSTICE NICOLA DAVIES DBE and LORD JUSTICE MALES - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME Appellant DEPARTMENT - and - YAGNESH DEVANI Respondent - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mr Nicholas Chapman (instructed by the Treasury Solicitor) for the Appellant Ms Samantha Broadfoot QC and Mr Raphael Jesurum (instructed by D.J. Webb & Co Solicitors) for the Respondent Hearing date: 12 February 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment was handed down remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email, release to BAILII and publication on the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary website. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be at 2pm on Thursday 6 May 2020. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. SSHD v Devani Lord Justice Underhill : INTRODUCTION 1. This appeal has a complicated and unsatisfactory procedural history, which it is necessary to set out in some detail before we can get to the issues. 2. The Respondent, to whom I will refer as Mr Devani, is a Kenyan businessman. He has been in this country since some time in 2009 or 2010, though he has not at any material time had leave to remain. 3. In 2011 Kenya made an extradition request in relation to serious allegations of fraud against Mr Devani; and a further request, also in relation to fraud, was made in 2013. -

ELA-ELD Framework, Vignette Collection

Vignette Collection of the English Language Arts/ English Language Development Framework for California Public Schools Kindergarten Through Grade Twelve ELA/ELD Framework Vignette Collection List of Vignettes ELA/ELD Framework Grade Vignette Title Chapter Page(s) TK 3.1. Retelling and Rewriting The Three Little Pigs, Integrated ELA/ 3 191–195 Literacy and ELD Instruction in Transitional Kindergarten TK 3.2. Retelling The Three Little Pigs Using Past Tense Verbs and 3 196–199 Expanded Sentences, Designated ELD Instruction in Transitional Kindergarten K 3.3. Interactive Storybook Read Aloud, Integrated ELA/Literacy and 3 228232 ELD Instruction in Kindergarten K 3.4. General Academic Vocabulary Instruction from Storybooks, 3 233–237 Designated ELD in Kindergarten 1 3.5. Interactive Read Alouds with Informational Texts, Integrated 3 263–269 ELA, Literacy, and Science Instruction in Grade One 1 3.6. Unpacking Sentences, Designated ELD Instruction in Grade One 3 269–274 2 4.1. Close Reading of Lily's Purple Plastic Purse (Narrative Text), ELA 4 341–345 Instruction in Grade Two 2 4.2. Discussing "Doing" Verbs in Chrysanthemum, Designated ELD 4 345–349 Instruction in Grade Two 3 4.3. Collaborative Summarizing with Informational Texts, Integrated 4 377–381 ELA and Science Instruction in Grade Three 3 4.4. Analyzing Complex Sentences in Science Texts, Designated ELD 4 382–386 Instruction in Grade Three 4 5.1. Writing Biographies, Integrated ELA and Social Studies 5 452–457 Instruction in Grade Four 4 5.2. General Academic Vocabulary in Biographies, Designated ELD 5 458–462 Instruction in Grade Four 5 5.3. -

Le Nouveau Président De Transition Centrafricain Est Une Femme

[Le nouveau président de transition centrafricain est une femme. Catherine Samba-Panza, maire de Bangui, a été élue par le CNT lundi avec 75 voix, contre Désiré Kolingba, fils d'un ancien président centrafricain. Le scrutin s'est déroulé à toute vitesse dans la grande salle de l'Assemblée. Chacun des huit candidats retenus a disposé de 10 minutes pour présenter sa candidature.Aussitôt sa victoire annoncée, Catherine Samba-Panza a salué l'élection d'une «fille, d'une mère et d'une sœur de Centrafrique ; c'est un événement de portée historique, qui s'inscrit dans les annales de ce pays».] BURUNDI : Le Burundi a réussi en 2013 à briser les barrières linguistiques au sein de la CEA Mardi 21 janvier 2014/Xinhua BUJUMBURA (Xinhua) - Le Burundi se félicite d'avoir réussi en 2013 à briser les barrières linguistiques au sein de la Communauté Est-Africaine (CEA), a déclaré lundi à Bujumbura Mme Léontine Nzeyimana, ministre burundaise à la Présidence chargé des Affaires de la CEA. Nzeyimana, qui présentait les grandes réalisations de son ministère en 2013, a précisé qu'au cours de l'année dernière, le gouvernement burundais était parvenu à renforcer les capacités de formation en langue anglaise pour 908 hauts cadres des différents ministères techniques, du secteur privé, de la société civile et des médias. Ce programme, a-t-il ajouté, a consisté à accélérer l' apprentissage de la langue anglaise et consolider la maîtrise de cette langue pour que le Burundi puisse devenir pratiquement bilingue et se positionner en ordre utile sur le marché du travail dans le cadre du protocole portant création du marché commun de la CEA. -

Border Thinking

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 21 Border Thinking Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) VOLUME 21 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly com- mitted partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contribu- tions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute- specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International re- viewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays. -

Sifat Magazine 2Nd Edition.Cdr

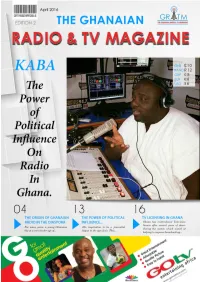

Contents PRODUCTION MANAGING EDITOR 03 EDITORIAL ENSURING PEACE ON THE AIRWAVES Nana Sifa Twum 04 THE ORIGIN OF GHANAIAN RADIO IN THE DIASPORA DEPUTY EDITOR 05 WHO STEPS IN THE SHOES OF KOMLA DUMOR? Robert Kyei-Gyau 06 NEW LEGISLATION TO CONTROL RADIO AND TV PROGRAMES CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Isaac Amo-Kyereme 08 KOJO OPPONG NKRUMAH EXETENDING BROADCASTING SKILLS INTO SOCIAL AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT... ASSISTANT EDITOR Neil Nelson 10 RADIO AND TV IN GHANA AND THE USE OF APPROPRIATE LANGUAGE EDITORIAL ASSISTANT 12 INTERNET BROADCASTING CREATING Mark Acheampong GLOBAL AUDIENCE 13 KABA DESIGN / LAYOUT THE POWER OF POLITICAL INFLUENCE ON RADIO TIN Consult IN GHANA 14 MICHAEL APPIAH-KUBI PHOTOGRAPHY “THE UNDENIABLE VOICE ON SANKOFA RADIO Akua Boatemaa Adjei & AFRICAN ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION... Nuzrat Baffoe 16 TV LICENSING IN GHANA A Klass Photos 18 WOMEN IN BROADCASTING IN GHANA CONTRIBUTORS 20 THE AKAN RADIO AND TV NEWS AND THE Joe Kingsley Eyiah AUDIENCE Kwadwo Acheampong 21 GHANAIAN RADIO AND TELEVISION MAGAZINE Kwame Twum LAUNCHED Gifty Darko 31 SOCIAL MEDIA & BROADCASTING MARKETING 34 PROPAGANDA & BROADCASTING Ebenezer Osei 35 THE NEED FOR DECORUM IN THE PRESENTATION Kwasi Apenuvor Mawuli OF NEWS ON GHANA'S FM RADIO STATIONS Gloria Osei 36 LOCAL LANGUAGE NEWS PRESENTATION Sammy Anim IN GHANA: ARE WE GETTING IT WRONG? CIRCULATION 37 KWASI GYAN APPENTENG GHANA – Frank Awuah – + 233(0) 244933617 CHAIRMAN – GHANA MEDIA COMMISION CANADA - Gabriel Odartei - 001647-895-5073 38 GROWING UP WITH RADIO IN GHANA UK – Thompson Goddard - + 44 0044776129366 GERMANY – Nana Basoa - +499408505571 MEMORIES OF A VILLAGE BOY USA Ike Amo-Kyereme - 0019515344611 39 GIBA SUCCEEDS IN HALTING.. -

Redefining Ghanaian Highlife Music in Modern Times

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2020 American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) e-ISSN :2378-703X Volume-4, Issue-1, pp-18-29 www.ajhssr.com Research Paper Open Access Redefining Ghanaian Highlife Music in Modern Times Mark Millas Coffie (Department of Music Education/ University of Education, Winneba, Ghana) ABSTRACT: Highlife, Ghana's first and foremost acculturated popular dance music has been overstretched by practitioners and patrons to the extent that, presently, it is almost impossible to identify one distinctive trait in most of the modern-day recorded songs categorised as highlife. This paper examines the distinctive character traits of Ghana's highlife music, and also stimulates a discourse towards its redefinition for easy recognition and a better understanding in modern times. Employing document review, audio review, interviews, and descriptive analysis, the paper reveals that the instrumental structure, such as percussion, guitar, bass, and keyboard patterns, is key in categorising highlife songs. The paper, however, argues that categorising modern-day recorded highlife songs based on timeline rhythms and drum patterns alone can be confusing and deceptive. The paper, therefore, concludes that indigenous guitar styles such as the mainline, yaa amponsah, dagomba, sikyi, kwaw, ᴐdᴐnson among others should be the chief criterion in recognising and categorising modern-day recorded highlife songs. KEYWORDS: Category, Highlife, Modern-day, Recognition, Timeline rhythm, Indigenous guitar styles I. INTRODUCTION Highlife music, one of the oldest African popular music forms originated from the Anglophone West African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. However, the term highlife was coined in Ghana around the 1920s (Collins, 1994). -

Religion Crossing Boundaries Religion and the Social Order

Religion Crossing Boundaries Religion and the Social Order An Offi cial Publication of the Association for the Sociology of Religion General Editor William H. Swatos, Jr. VOLUME 18 Religion Crossing Boundaries Transnational Religious and Social Dynamics in Africa and the New African Diaspora Edited by Afe Adogame and James V. Spickard LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Religion crossing boundaries : transnational religious and social dynamics in Africa and the new African diaspora / edited by Afe Adogame and James V. Spickard. p. cm. -- (Religion and the social order, ISSN 1061-5210 ; v. 18) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-90-04-18730-6 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Blacks--Africa--Religion. 2. Blacks--Religion. 3. African diaspora. 4. Globalization--Religious aspects. I. Adogame, Afeosemime U. (Afeosemime Unuose), 1964- II. Spickard, James V. III. Title. IV. Series. BL2400.R3685 2010 200.89'96--dc22 2010023735 ISSN 1061-5210 ISBN 978 90 04 18730 6 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Speaker Biographies an African Conversation Africa Ahead: the Next 50 Years

2013 Ibrahim Forum Speaker Biographies An African Conversation Africa Ahead: The Next 50 Years Sunday, 10th November African Union Conference Centre, Addis Ababa Addis Ababa, 10.11.2013 2013 Ibrahim Forum 1 Held annually since 2010, the Ibrahim Forum aims to tackle specific issues that are of critical importance to Africa, and require both committed leadership and governance. Bringing together a diverse range of high-level African stakeholders belonging to various public and private constituencies, as well as selected non-African partners, the Forum is an open and frank discussion. It aims to go beyond stating issues and renewing commitments by defining pragmatic strategies, operational action points and shared responsibilities. Since this year sees the celebration of the 50th Anniversary of African unity, the focus of the 2013 Ibrahim Forum is on the major opportunities and challenges the continent will have to tackle over the next 50 years. To facilitate the debate, the panels will be organised around the four Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) categories – Safety & Rule of Law, Participation & Human Rights, Sustainable Economic Opportunity and Human Development – all of which are areas requiring exceptional leadership and governance. Each of the panels will aim to address four key questions: • What are the key priorities? • Who are the key actors responsible for driving and implementing the agenda? • What resources are available/necessary to ensure success and progress? • What indicators/mechanisms can be used to monitor implementation and measure results? Addis Ababa, 10.11.2013 IBRAHIM FORUM PANELS Panel 1 Panel 2 ‘Human Development’ ‘Sustainable Economic Opportunity’ The population of a country is a leader’s Recent decades have registered major shifts in fundamental unit of responsibility. -

Ghana: Changing Values/ Changing Technologies

CULTURAL HERITAGE AND CONTEMPORARY CHANGE SERIES II, AFRICA, VOLUME 5 GHANA: CHANGING VALUES/ CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES Ghanian Philosophical Studies, II Edited by Helen Lauer The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2000 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Ghana: changing values/changing technology: Ghanaian philosophical studies / edited by Helen Lauer. p.cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series II, Africa; vol. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Technology—Ghana. 2. Technology—Philosophy. I. Lauer, Helen. II. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, II. III. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, two. IV. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, 2. V. Series. T28.G4C37 1999 99-37506 338.966706—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-56518-144-1 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iii Preface George F. McLean xiii Introduction Helen Lauer 1 PART I. CULTURE AND CHANGE Chapter I. Culture: the Human Factor in African Development Kofi Anyidoho 19 Chapter II. Modern Technology, Traditional Mysticism and Ethics in Akan Culture George P. Hagan 31 Chapter III. Traditional Ga and Dangme Attitudes towards Change and Modernization Joshua N. Kudadjie 53 PART II. SOCIETY AND CHANGES OF VALUES Chapter IV. Counterproductive Socioeconomic Management in Ghana A.O. Abudu 79 Chapter V. Informalization and Ghanaian Politics Kwame A. Ninsin 113 Chapter VI. Manipulation of the Mass Media in Ghana’s Recent Political Experience Joseph Osei 139 PART III. TECHNOLOGY AND HUMAN CHANGE Chapter VII. Plant Biodiversity, Herbal Medicine, Intellectual Property Rights and Industrially Developing Countries: Socio-economic, Ethical and Legal Implications Ivan Addae-Mensah 165 Chapter VIII. -

African Pneumatology in the British Context: a Contemporary Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository AFRICAN PNEUMATOLOGY IN THE BRITISH CONTEXT: A CONTEMPORARY STUDY By CHIGOR CHIKE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Philosophy, Theology and religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham November 2011 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The large numbers of Africans that have come to live in Britain in the last few decades have necessitated a better understanding of African Christianity. Focusing on Pneumatology, this study sets out to achieve such understanding by first undertaking a research of a church in London with a congregation made up of mostly Africans. This fieldwork yielded twelve concrete statements or “pattern-theories” on what the church members believe about the Holy Spirit. At that point, a review of existing literature was used to understand these “pattern-theories” more deeply. A second fieldwork was then carried out whereby two of these twelve “pattern-theories” were tested on a larger number of Africans drawn from four different Christian denominations. -

Winmat Primary English Standards-Based Facilitator’S Guide 5

Winmat Primary English Standards-Based Facilitator’s Guide 5 L. B. Quansah, Innocent Awuttey Published by WINMAT PUBLISHERS LTD No. 27 Ashiokai Street P.O. Box 8077 Accra North, Ghana www.winmatpublishers.com Tel: +233 552 570 422 / +233 302 978 784 www.winmatpublishers.com [email protected] ISBN: 978-9988-0-4819-8 Text © L. B. Quansah, Innocent Awuttey 2020 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Typeset: Fine Precision Cover design by: Josephine Anderson Edited by: Dr. Akosua Dzifa Eghan Dorothy Hammond Eyra Doe Agatha Akonor-Mills The publishers have made every effort to trace all copyright holders but if they have inadvertently overlooked any, they will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................... V Unit 1: Who are you?....................................................... 1 Unit 2 : Giving and following instructions....................... 8 Unit 3 : Using paragraphs................................................. 14 Unit 4 : Writing friendly letters......................................... 20 Unit 5 : Describing an event............................................. 25 Unit 6 : Telling stories....................................................... 31 Unit 7 : Stories in different forms -

Yaa Amponsah and the Rhythm at the Heart of West African Guitar

“You can’t run away from it! The melody will always appear!” Yaa Amponsah and the Rhythm at the Heart of West African Guitar A thesis submitted by Nathaniel C. Braddock in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Tufts University August 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey Summit © 2020, Nathaniel C. Braddock Abstract The song “Yaa Amponsah” is held by Ghanaian musicians as the key to all highlife music. However, Amponsah occupies two spaces: that of a specific song with folkloric and historical origin stories, and that of a compositional form—or “Rhythm”—from which countless variations have evolved over the past century. This thesis seeks to define Amponsah as a style where certain characteristics are not always clear but are continually present and recognizable cross-nationally. Using musical analysis and ethnographic interviews with West African guitarists, I explore the movement of Amponsah across generations and national boundaries, drawing larger conclusions that have implications for understanding the transmission of cultural practice and embedded cultural memory carried within a specific musical expression. The Rhythm makes impactful appearances in the music of neighboring countries, becoming entwined with the Mami Wata myth, further complicating our understanding of ownership and origin, and bringing this song to the center of a debate regarding ownership of folkloric intellectual property and the relationship between developing nations and global capital. i Acknowledgements My journey has been supported by numerous people, and I wish now to salute their love, friendship, and guidance. My wife Julie Shapiro and son Phineas have given the most during this process, but I also owe much to my parents Robert and Sarah Braddock whose respect of my independence enabled me to follow the less trodden paths.