Honours in Australia: Globally Recognised Preparation for a Career in Research (Or Elsewhere)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme Specification and Curriculum Map (PSP) 1

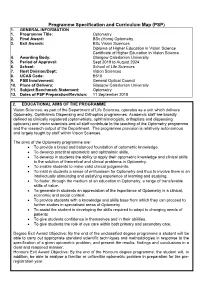

Programme Specification and Curriculum Map (PSP) 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Programme Title: Optometry 2. Final Award: BSc (Hons) Optometry 3. Exit Awards: BSc Vision Sciences Diploma of Higher Education in Vision Science Certificate of Higher Education in Vision Science 4. Awarding Body: Glasgow Caledonian University 5. Period of Approval: Sept 2019 to August 2024 6. School: School of Life Sciences 7. Host Division/Dept: Vision Sciences 8. UCAS Code: B510 9. PSB Involvement: General Optical Council 10. Place of Delivery: Glasgow Caledonian University 11. Subject Benchmark Statement: Optometry 12. Dates of PSP Preparation/Revision: 11 September 2018 2. EDUCATIONAL AIMS OF THE PROGRAMME Vision Sciences, as part of the Department of Life Sciences, operates as a unit which delivers Optometry, Ophthalmic Dispensing and Orthoptics programmes. Academic staff are broadly defined as clinically registered (optometrists, ophthalmologists, orthoptists and dispensing opticians) and vision scientists and all staff contribute to the teaching of the Optometry programme and the research output of the Department. The programme provision is relatively autonomous and largely taught by staff within Vision Sciences. The aims of the Optometry programme are: To provide a broad and balanced foundation of optometric knowledge. To develop practical optometric and ophthalmic skills. To develop in students the ability to apply their optometric knowledge and clinical skills to the solution of theoretical and clinical problems in Optometry. To enable students to make valid clinical judgements. To instil in students a sense of enthusiasm for Optometry and thus to involve them in an intellectually stimulating and satisfying experience of learning and studying. To foster, through the medium of an education in Optometry, a range of transferable skills of value. -

PATHWAYS to Phd and Other Doctoral Degrees

You are eligible for admission to a Doctoral Degree if you have one of the following qualifications with at least 40CP (or equivalent) research component, having achieved specific Thesis and GPA requirements: • Bachelor Honours Degree (AQF Level 8) • Masters Degree, Coursework, Research, Extended (AQF Level 9). • Graduate Diploma of Research Studies – each Academic Group at Griffith has discipline specific qualifications If you do not have one of the qualifications listed above which includes the required minimum research component, based on your highest qualification achieved you will be eligible for admission to a Doctoral degree by undertaking further study as follows, provided you achieve specific Thesis and GPA requirements: Having successfully completed one of the following awards: • Bachelor Degree (AQF Level 7) • Graduate Certificate / Graduate Diploma (AQF Level 8) that does not contain at least 40CP research component • Masters Degree (Coursework - AQF Level 9) that does not contain at least 40CP research component Bachelor Honours Complete one of the following awards to be eligible for admission to a Doctoral Degree: (AQF 8) (1 Year) • Bachelor Honours degree (1 year, 80CP) with Class I or IIA • Postgraduate coursework or research program with at least 40CP or equivalent research component. Click here for a complete list of approved programs at Griffith University which provide this pathway to PhD. PATHWAYS to PhD and other Doctoral Degrees Bachelor Honours (AQF 8) (4+Years) with Class I or IIA Bachelor Honours Masters Research -

Optometry (Accelerated Route) Bsc (Hons)

Faculty of Life Sciences Programme Specification Programme title: BSc (Hons) Optometry (Accelerated Route) Academic Year: 2018/19 Degree Awarding Body: University of Bradford Final and interim award(s): BSc (Honours) [Framework for Higher Education BSc (Hons) Vision Science [for Qualification Level 6] students gaining an award Diploma of Higher Education [Framework for but who do not meet the Higher Education Qualifications level 5] Clinical Competence requirements for GOC] Certificate of Higher Education [Framework for Higher Education Qualifications level 4] Programme accredited by (if General Optical Council (GOC) appropriate): Programme duration: 16 weeks part-time and 45 weeks full-time QAA Subject benchmark Optometry (2015) statement(s): Date of Senate Approval: Date last confirmed and/or December 2015 minor modification approved by Faculty Board Introduction Optometrists are healthcare professionals whose primary role involves measurement and optical correction of sight defects (refractive errors), and detection and recognition of ocular disease and dysfunction. Optometrists are trained to supply and fit (dispense) optical appliances such as spectacles, contact lenses and low vision aids. Optometrists are also trained to undertake assessment of binocular vision and to diagnose and manage (non-pathological) binocular vision anomalies. In the United Kingdom (UK), the optometry profession is the largest provider of primary eye care, and is responsible for a significant proportion of ophthalmic referrals to the secondary care sector. Many of these referrals are of patients with sight-threatening conditions, including cataract, glaucoma, hypertension and diabetes. The overall aim of the accelerated degree programme in optometry is to build upon the student’s previous experience as a dispensing optician in order to allow a student to carry out all the functions described above, to communicate skilfully and knowledgeably with patients and other professionals, and to uphold high standards of professional integrity and behaviour. -

Classifying Educational Programmes

Classifying Educational Programmes Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries 1999 Edition ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Foreword As the structure of educational systems varies widely between countries, a framework to collect and report data on educational programmes with a similar level of educational content is a clear prerequisite for the production of internationally comparable education statistics and indicators. In 1997, a revised International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference. This multi-dimensional framework has the potential to greatly improve the comparability of education statistics – as data collected under this framework will allow for the comparison of educational programmes with similar levels of educational content – and to better reflect complex educational pathways in the OECD indicators. The purpose of Classifying Educational Programmes: Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries is to give clear guidance to OECD countries on how to implement the ISCED-97 framework in international data collections. First, this manual summarises the rationale for the revised ISCED framework, as well as the defining characteristics of the ISCED-97 levels and cross-classification categories for OECD countries, emphasising the criteria that define the boundaries between educational levels. The methodology for applying ISCED-97 in the national context that is described in this manual has been developed and agreed upon by the OECD/INES Technical Group, a working group on education statistics and indicators representing 29 OECD countries. The OECD Secretariat has also worked closely with both EUROSTAT and UNESCO to ensure that ISCED-97 will be implemented in a uniform manner across all countries. -

Degrees, Diplomas and Certificates Awarded in Conjunction with the Glasgow School of Art

Calendar 2011-12 DEGREES, DIPLOMAS AND CERTIFICATES AWARDED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART CONTENTS LIST Page Appeals by Students ........................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 4 Degrees of Bachelor of Arts in Design, Bachelor of Arts in Fine Art, Bachelor of Arts in Communication Design, Bachelor of Arts in Interior Design, and Bachelor of Arts in Silversmithing and Jewellery Design .............. 5 Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Design (Part-Time) Ceramics ............................ 8 Degree of Bachelor of Architecture .................................................................. 8 Diploma in Architecture and Master of Architecture (by Conversion) Degree ........................................................................................................... 11 Degrees in Product Design Engineering ........................................................ 13 Degrees of Bachelor of Design (Product Design) and Master of European Design (Product Design) ................................................................ 14 Degree of Bachelor of Design in Fashion Textiles ......................................... 17 Degree of Bachelor of Deisgn in Digital Culture ............................................. 20 Taught Postgraduate Awards at The Glasgow School of Art ......................... 22 Degree of Master of Science in Product Design Engineering........................ -

A. Bachelor of Arts Degree the University Offers a Major Or Honours Program Within the Bachelor of Arts Degree.Both Programs Have the Following Basic Requirements: 1

St. Thomas University offers bachelor degree programs in Arts, Applied Arts, Social Work, and Education. St. Thomas University awards degrees and certificates at spring and summer convocation and through early conferral on March 1 and November 1. A. Bachelor of Arts Degree The University offers a Major or Honours program within the Bachelor of Arts Degree.Both programs have the following basic requirements: 1. Successful completion of 120 credit hours. 2. A concentration in a specific subject area or interdisciplinary grouping constituting a Major or Honours. 3. No more than 60 credit hours in one subject within the 120 credit hours required for the degree except by special permission of the Senate Admissions and Academic Standing committee. 4. A minimum of 72 credit hours at the intermediate (2000) level and above. 5. An annual GPA of at least 2.0 in the academic year of graduation or on the last 30 credit hours of study. 6. Group distribution requirements as outlined below. Note: The first year of a program leading to a LLB degree in a faculty of law at a Canadian university recognized by the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) may be substituted for the fourth year (30 credit hours) of the BA Degree program with approval of the Registrar. The Bachelor of Arts curriculum consists of a subject concentration and a prescribed distri- bution of courses. 1. Subject Major Normally, 36 credit hours in one subject constitute a Major. Currently the University offers Major programs in the following subject areas: Anthropology Great Books Political Science Catholic Studies History Psychology Communications and Human Rights Religious Studies Public Policy Interdisciplinary Studies Science & Technology Studies Criminology International Relations Sociology Economics Journalism Spanish and Latin American Studies English Mathematics Women’s Studies & Gender Environment and Society Native Studies French Media Studies Gerontology Philosophy The specific course requirements for a Major in a particular subject area are described in Section Six. -

The Law Degree with Honours

THE LAW DEGREE WITH HONOURS What is Honours? What is Honours & Advantages - http://www.uow.edu.au/student/honours/whatis/index.html The Code of Practice – Honours sets out the responsibilities of all parties involved in managing students undertaking Honours Programs. Please see http://www.uow.edu.au/about/policy/UOW058661.html Getting an Honours LLB There are two paths to an Honours degree in law. You can have it based on your weighted average mark (WAM), or you can do a RESEARCH HONOURS. That involves a year of specialised study and research on a topic that you work out with a supervisor. You can combine that with an Honours year in another School: one thesis, jointly supervised. If you have a WAM approaching 70, and would like to know more about these options, contact the Honors Co-ordinator before the end of Spring Session. Honours Co-ordinator The Honours Co-ordinator for 2014 is Dr Cassandra Sharp. Room 67.221 Telephone: 02 4221 5532 Email: [email protected] There are three methods by which students may be awarded the LLB degree with honours: 1. WAM-Based Honours All students who achieve an overall WAM of 70% or better AND who complete LLB 313 Legal Research Project as one of their 8 credit point electives will be awarded LLB (Hons). Honours grades are as follows: • Honours Class I 75% to 100% • Honours Class II, Division 1 72.5% to less than 75% • Honours Class II, Division 2 70% to less than 72.5% LLB 313 Legal Research Project is an elective in the LLB program. -

Qualifications and Credit Framework (PDF)

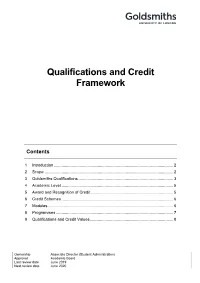

Qualifications and Credit Framework Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 2 Scope .................................................................................................................. 2 3 Goldsmiths Qualifications .................................................................................... 3 4 Academic Level ................................................................................................... 5 5 Award and Recognition of Credit ......................................................................... 5 6 Credit Schemes ................................................................................................... 6 7 Modules ............................................................................................................... 6 8 Programmes ........................................................................................................ 7 9 Qualifications and Credit Values .......................................................................... 8 Ownership Associate Director (Student Administration) Approval Academic Board Last review date June 2019 Next review date June 2020 1 Introduction 3.1.1 All programmes of study must be approved through the Goldsmiths procedures for the approval, amendment and review of programmes and modules. They must meet the requirements of the Goldsmiths Credit and Qualifications Framework. 1.1 General 1.1.1 The policies and procedures set out in this document -

University of Aberdeen

University of Aberdeen About the Department of Geography and Environment Geography at Aberdeen runs a modular system, so you have the flexibility to follow a Single Honours Degree with plenty of choice and diversity, or to study Geography as part of a Joint Honours Degree with another subject. To a large extent you can shape your own degree, to suit your particular interests and career plans. You can choose between studying Geography as either a Bachelor of Science (BSc) or Master of Arts (MA) degree programme. Both can be taken as four-year Honours degrees, or three-year Designated degree programmes. The main difference between the BSc and MA programmes is in the subsidiary subjects taken alongside Geography. For the BSc these will be mainly science subjects, while MA students will take subsidiary courses in the humanities and social sciences. All of our teaching is research-led, delivered by staff who are actively investigating some of the most important problems facing the world today – problems with social and environmental dimensions which geographical knowledge can help us understand and resolve. This ensures that our courses are current, exciting and reflect the cutting edge of Geographical Research. Need more reasons to study Geography at Aberdeen? Our graduates have an excellent record of going on to successful Careers beyond university. Our students and staff run a vibrant Geography Society, with regular events all year including the legendary Annual Geography Ball. And all of this is hosted within the University of Aberdeen's King's Campus, with its beautiful historic buildings and state-of-the-art facilities, including the New Library and Olympic Standard Sports Village. -

Structure and Requirements of Qualifications Awarded by Griffith University

Structure and Requirements of Qualifications Awarded by Griffith University Approving authority Academic Committee Approval date 1 October 2021 (1/2021 meeting) Advisor Registrar | Student Life [email protected] Next scheduled review 2023 http://policies.griffith.edu.au/pdf/Structure and Requirements of Document URL Qualifications.pdf TRIM document 2021/0000286 Description This policy prescribes the definitions, general elements and structural features which apply to all the qualifications of Griffith University. Related documents Bachelor Degree (AQF Level 7) Policy Bachelor Honours Degree (AQF Level 8) Policy Postgraduate Qualifications (AQF Level 8 & 9) Policy Program and Course Policy Higher Degree Research Policy Role Statement Program Director Fees and Charges Policy Student Administration Policy Academic Awards, Programs, Nomenclature and Abbreviations Academic Calendar Procedure Assessment Policy Academic Standing, Progression and Exclusion Policy [Definitions] [Program] [Award Qualifications] [Course] [Credit Point] [Trimesters and Teaching Periods] [Program Standard Length] [Annual Academic Load] [Program Mode] [Student Academic Load and Mode of Attendance] [Program Requirements] [Changes to Program Requirements] [Progress] [Award of Qualification] [Variation to Program Requirements] 1. DEFINITIONS AQF qualification is a completed University accredited program of learning that leads to formal certification that a graduate has achieved the learning outcomes as described in the AQF. Capstone Course is a course which offers students nearing graduation the opportunity to summarise evaluate and integrate learning from across a range of learning experiences to engage with a task which addresses a contemporary issue or problem facing a particular discipline or profession. Components of a qualification refer to units of academic work or courses, the completion of which leads to an AQF qualification. -

Faculty of Arts Honours Guidelines

Faculty of Arts Honours Guidelines 1. SCOPE AND APPLICATION 2. ENTRY CRITERIA 3. PROGRAM STRUCTURE 3.1. Full-time Honours 3.2. Part-time Honours 4. STUDENT WORKLOAD 5. ASSESSMENT 6. COORDINATION 1. SCOPE AND APPLICATION These Guidelines apply to all staff and students at the University of Adelaide from Semester 1, 2021 unless otherwise excluded in the scope of an associated procedure. The Faculty of Arts Honours Guidelines are intended to operate in conjunction with the following University of Adelaide Policies: • Coursework Academic Programs Policy • Assessment for Coursework Programs Policy • Modified Arrangements for Coursework Assessment Policy As of Semester 1, 2021, these Honours programs are available within the Faculty of Arts: 1. Bachelor of Arts (Hons) • Anthropology • Chinese Studies • Classics • Creative Writing • Criminology • English • French Studies • Gender Studies • Geography, Environment and Population • German Studies • History • International Development • Japanese Studies • Philosophy • Politics and International Relations • Sociology • Spanish Studies 2. Bachelor of Criminology (Hons) 3. Bachelor of International Development (Hons) 4. Bachelor of Social Sciences (Hons) 5. Bachelor of Media (Hons)* 6. Bachelor of Environmental Policy and Management (Hons) 7. Bachelor of International Relations (Hons) 8. Bachelor of Languages (Hons) • Honours Chinese Studies • Honours French Studies • Honours German Studies • Honours Japanese Studies • Honours Spanish Studies • Combined Honours in two languages comprising 6 units of -

Working out Your Class of Honours

Working out your Class of Honours The credit needed for an honours degree Qualification for an OU honours degree requires you to successfully complete at least 360 credits. Of these, at least 240 must be at OU second level or higher and, of those, at least 120 must be at OU third level. The honours classification process We calculate the class of your bachelors honours degree using the results on all your graded OU or approved collaborative scheme modules at OU second level or higher - up to 240 credits. For some of our degrees, up to 240 credits can come from an award of credit transfer in recognition of study successfully completed elsewhere. Your performance in any work for which an award of credit transfer has been made is not taken into account so, for some students on some of our degrees, the calculation of the class of honours could be based on as little as 120 credits from modules at OU third level. But in most cases, it will be the full 240 credits. Each degree has a rule that specifies the modules that can be counted in classification. You can check this by looking at the information about your particular degree on our website at www.open.ac.uk/student. Within that rule, we always choose your best grades. Normally these will be given for each module as one of Distinction (1), Pass grade 2, Pass grade 3 or Pass grade 4. We take the grades you obtain in your best 120 credits at OU third level and, using the calculation shown in examples 1 and 2 below, we give them twice their score.