Capital Taxation During the U.S. Great Depression∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

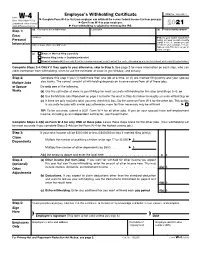

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Self-Employment Guide a Resource for SNAP and Cash Programs

Economic Assistance and Employment Supports Division Self-Employment Guide A resource for SNAP and Cash Programs Self-Employment Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 SE 01.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 SE 02.0 Definition of a self-employed person ................................................................. 3 SE 03.0 Self-employment ownership types ..................................................................... 3 SE 03.1 Sole Proprietorship ........................................................................................ 3 SE 03.2 Partnership ..................................................................................................... 4 SE 03.3 S Corporations ............................................................................................... 5 SE 03.4 Limited Liability Company (LLC) .................................................................... 6 SE 04.0 Method of Calculation ........................................................................................ 7 SE 05.0 Verifications ....................................................................................................... 7 SE 06.0 Self-employment certification steps ................................................................. 10 SE 07.0 Self-employment Net Income Calculation – 50% Method ............................... -

Chapter 1: Meet the Federal Income

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_1 rev0 page 1 1. Meet the Federal Income Tax The tax code has become near incomprehensible except to specialists. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Chairman, Senate Finance Committee, August 11, 1994 I would repeal the entire Internal Revenue Code and start over. Shirley Peterson, Former Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 3, 1994 Tax laws are so complex that mechanical rules have caused some lawyers to lose sight of the fact that their stock-in-trade as lawyers should be sound judgment, not an ability to recall an obscure paragraph and manipulate its language to derive unintended tax benefits. Margaret Milner Richardson, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 10, 1994 It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow. Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, The Federalist, no. 62 the federal income tax is a complete mess. It’s not efficient. It’s not fair. It’s not simple. It’s not compre- hensible. It fosters tax avoidance and cheating. It costs billions of dollars to administer. It costs taxpayers bil- lions of dollars in time spent filling out tax forms and Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_2 rev0 page 2 2 The Flat Tax other forms of compliance. -

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in How Unemployment Benefits Are Taxed for Tax Year 2020

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in how Unemployment Benefits are taxed for Tax Year 2020 On March 31, 2021, Governor DeWine signed into law Sub. S.B. 18, which incorporates recent federal tax changes into Ohio law effective immediately. Specifically, federal tax changes related to unemployment benefits in the federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 will impact some individuals who have already filed or will soon be filing their 2020 Ohio IT 1040 and SD 100 returns (due by May 17, 2021). Ohio taxes unemployment benefits to the extent they are included in federal adjusted gross income (AGI). Due to the ARPA, the IRS is allowing certain taxpayers to deduct up to $10,200 in unemployment benefits. Certain married taxpayers who both received unemployment benefits can each deduct up to $10,200. This deduction is factored into the calculation of a taxpayer’s federal AGI, which is the starting point for Ohio’s income tax computation. Some taxpayers will file their 2020 federal and Ohio income tax returns after the enactment of the unemployment benefits deduction, and thus will receive the benefit of the deduction on their original returns. However, many taxpayers filed their federal and Ohio income tax returns and reported their unemployment benefits prior to the enactment of this deduction. As such, the Department offers the following guidance related to the unemployment benefits deduction for tax year 2020: • Taxpayers who do not qualify for the federal unemployment benefits deduction. o Ohio does not have its own deduction for unemployment benefits. Thus, if taxpayers do not qualify for the federal deduction, then all unemployment benefits included in federal AGI are taxable to Ohio. -

Economic Considerations for Raising the US Corporate Income Tax Rate

Economic considerations for raising the US corporate income tax rate James Mackie Quantitative Economics and Statistics (QUEST) Group Ernst & Young LLP May 2021 Outline • Summary • Macroeconomic analysis of raising the corporate income tax rate from 21% to 28% • Problems with raising the corporate income tax rate now, as the economy struggles to emerge from a recession • The distribution of the burden of the corporate income tax • How does the US corporate tax rate and corporate tax revenue compare to those in the OECD and BRIC Page 2 Economic considerations for raising the top US corporate income tax rate Summary • Macroeconomic analysis • The Biden administration has proposed raising the corporate income tax rate from 21% to 28% as part of a larger set of tax and spending proposals. • The spending proposals include funding infrastructure and other potentially productivity enhancing activities. • This study focuses on the macroeconomic effects of the proposed increase in the corporate income tax where some of the revenue raised is used to pay for infrastructure or other potentially productivity enhancing public investments. • The study finds that even when 75% of the revenue raised is used to fund productivity enhancing public investments, GDP, private investment, labor income and jobs decline. Page 3 Economic considerations for raising the top US corporate income tax rate Summary (continued) • Problems with raising the corporate tax now, as the economy is in or just emerging from a recession • Tax cuts, not tax increases, are typically seen as the appropriate response to an economic downturn. • While the economy appears to be recovering, that recovery remains fragile. -

The Negative Income Tax: Would It Discourage Work?

The negative income tax: would it discourage work? Advocates of the negative income tax often contend that such a program would provide stronger work incentives than conventional welfare benefits; evidence from recent tests indicates that this assumption may not be well founded ROBERT A. MOFFITT Would government cash transfer payments to the poor, periment was conducted in the New Jersey-Pennsylva- in the form of a negative income tax, discourage work nia area because of its high density of urban poor, effort among recipients? The strongest evidence for the because it initially had no Aid to Families with Depen- existence of such a disincentive comes from four income dent Children Unemployed Parent Program for hus- maintenance experiments, each of which tested the ef- band-wife couples, and because area government fects of the negative income tax on samples of the Na- officials were very receptive. The rural experiment was tion's low-income population. The findings from the designed to study a different group of the population, experiments have been released in uneven spurts, as and thus focused on two States with different types of they have become available. This article summarizes the low-income populations and agricultural bases. Seattle results of all four experiments, shows what we have and Denver were chosen to represent the West, and in learned from them, and discusses their limitations in the case of Denver, to study a Chicano subpopulation . providing correct estimates of work disincentive effects .' Finally, Gary was selected because its population per- The experiments were conducted over a number of mitted concentration on black female family heads in years in selected "test bore" sites across the country : the Aid to Families with Dependent Children Program, New Jersey and Pennsylvania (1968-72); rural areas of and because of receptive local officials . -

Bold Ideas for State Action

GETTY/GEORGE ROSE Bold Ideas for State Action By the Center for American Progress May 2018 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Bold Ideas for State Action By the Center for American Progress May 2018 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Economy 17 Education 30 Early childhood 36 Health care 43 Restoring democracy 50 Clean energy and the environment 57 Women and families 64 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer rights 67 Immigration 72 Criminal justice 79 Gun violence prevention 84 Conclusion 85 Endnotes Introduction and summary The past several decades have not been kind to America’s working families. Costs have skyrocketed while wages remain stagnant. Many of the jobs that have returned in the wake of the Great Recession have often offered lower wages and benefits, leaving Americans without college degrees particularly vulnerable. Fissures in the country are more apparent than ever, as access to opportunity is radically different between communities; the wealthiest grow richer while working families find themselves increasingly strapped. As a result of perpetual underinvestment in infrastructure, education, and other domestic priorities, the future for too many Americans looks increasingly grim, unequal, and uncertain. Federal policies passed or implemented in the past year will largely result in expanded inequality, not in rebuilding the middle class. The new tax law, as pushed by the Trump administration and congressional leadership, gives billions of dollars in tax cuts to companies and the wealthiest Americans instead of providing further support to those who need it most. As was true in the 2000s and more recently in states such as Kansas, showering tax giveaways on the wealthiest individuals and corporations does not create jobs or raise wages.1 Rather, when the baseless promises of economic growth do not materialize, the result is lower revenues and, ultimately, major cuts to critical investments in areas such as schools, infrastructure, and public services. -

Form 1099G PO Box 826880, Sacramento, CA 94280-0001 Available to Low to Moderate Income Working Individuals and Families

Tax Information Important Tax Information - Keep for your records. *See Reverse Side for Easy Opening Instructions* PRESORTED FIRST-CLASS MAIL You may qualify for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) depending on U.S. POSTAGE PAID your annual earnings. The federal EITC is a refundable federal income tax credit SACRAMENTO, CA Form 1099G PO Box 826880, Sacramento, CA 94280-0001 available to low to moderate income working individuals and families. The EITC PERMIT NO. 800 has no effect on eligibility for Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, food OFFICIAL BUSINESS stamps, or most other temporary assistance for those in need. Even if you do not PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300 owe federal taxes, you must file a tax return to receive the EITC. For more information regarding your eligibility for the EITC, or to obtain the necessary forms to apply for this refundable tax credit, visit the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) website at www.irs.gov/eitc or contact the IRS by phone. What is a 1099G form? Form 1099G is a record of the total taxable income the California Employment Development Department (EDD) issued you in a calendar year, and is reported to the IRS. You will receive a Form 1099G if you collected OMB NO. 1545-0120 COPY B FORM 1099G CERTAIN GOVERNMENT PAYMENTS FOR RECIPIENT REPORT OF TAXABLE UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION PAYMENTS FROM THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 2020 unemployment compensation (UC) from the EDD and Form 1099G Rev. 37 Employment Development Department Recipient's Name Social Security Number must report it on your federal tax return as income. UC is Unemployment Insurance Integrity and Accounting T Division - MIC 16A P.O. -

Instructions for Form 8994 (Rev. January 2021)

Userid: CPM Schema: Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 10 Draft Ok to Print instrx AH XSL/XML Fileid: … ns/I8994/202101/A/XML/Cycle08/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 10 14:46 - 22-Jan-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Department of the Treasury Instructions for Form 8994 Internal Revenue Service (Rev. January 2021) Employer Credit for Paid Family and Medical Leave Section references are to the Internal Revenue Code Eligible Employer unless otherwise noted. An eligible employer is an employer with a written policy in Future Developments place that provides paid family and medical leave and For the latest information about developments related to satisfies minimum paid leave requirements (see Minimum Form 8994 and its instructions, such as legislation Paid Leave Requirements, later). In addition, if the enacted after they were published, go to IRS.gov/ employer employs any qualifying employees who aren’t Form8994. covered by title I of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), the employer’s written policy must include What’s New “non-interference” language. Periodic updating. Form 8994 and its instructions will no Non-interference language. If an employer employs at longer be updated annually. Instead, they’ll only be least one qualifying employee who isn’t covered by title I updated when necessary. See Which Revision To Use. of the FMLA (including any employee who isn’t covered by title I of the FMLA because he or she works less than New employment tax credits. You may have claimed 1,250 hours per year), the employer must include coronavirus (COVID-19)-related employment credits on “non-interference” language in its written policy and an employment tax return such as Form 941, Employer’s comply with this language to be an eligible employer. -

Practical Guidance at Lexis Practice Advisor

® Practical guidance at Lexis Practice Advisor Lexis Practice Advisor® offers beginning-to-end practical guidance to support attorneys’ work in specific legal practice areas. Grounded in the real-world experience of expert practitioner-authors, our guidance ranges from practice notes and legal analysis to checklists and annotated forms. In addition, Lexis Practice Advisor provides everything you need to advise clients and draft your work product in 14 different practice areas. Taxation and Reporting of Settlement Payments for Employment-Related Lawsuits by William Hays Weissman, Littler Mendelson, P.C. This practice note outlines the most common tax and reporting issues associated with the settlement of employment-related litigation. The proliferation of employment-related litigation over the last decade has led to a significant numbers of settlements. Attorneys often overlook or fail to address the tax consequences of such litigation until after the parties reach a settlement, leading to potential issues for both the employer and employee. We address the following issues to help you properly handle tax and reporting issues related to settlements of employment-related claims: • Key steps for determining taxation and reporting of settlement payments • Taxation and reporting of wages • Taxation and reporting of non-wage payments • IRS chart showing taxation and reporting requirements for various types of payments • Unique issues concerning taxation and reporting of attorney’s fees • IRS charts showing taxation and reporting requirements for attorney’s fees • Tax consequences of settlement allocations • Guidance for pushing back on opposing counsel who request and/or demand improper settlement allocations Key Steps for Determining Taxation and Reporting of Settlement Payments The IRS has laid out four key steps for determining taxation and reporting requirements for settlements. -

Workforce Development and Unemployment Insurance Provisions

ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA Implementation of the MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNE- SOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NE- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: VADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLA- HOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VERMONT VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WEST Workforce Development and VIRGINIA WISCONSIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CON- Unemployment Insurance ProvisionsNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEW HAMP- SHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH FINAL REPORT CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAR- OLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VER- October 2012 MONT VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WEST VIRGINIA WISCON- SIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KEN- TUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA