Fort Chipewyan 1788-1988

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2: Baseline, Section 13: Traditional Land Use September 2011 Volume 2: Baseline Studies Frontier Project Section 13: Traditional Land Use

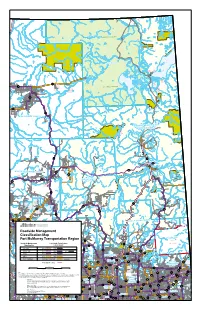

R1 R24 R23 R22 R21 R20 T113 R19 R18 R17 R16 Devil's Gate 220 R15 R14 R13 R12 R11 R10 R9 R8 R7 R6 R5 R4 R3 R2 R1 ! T112 Fort Chipewyan Allison Bay 219 T111 Dog Head 218 T110 Lake Claire ³ Chipewyan 201A T109 Chipewyan 201B T108 Old Fort 217 Chipewyan 201 T107 Maybelle River T106 Wildland Provincial Wood Buffalo National Park Park Alberta T105 Richardson River Dunes Wildland Athabasca Dunes Saskatchewan Provincial Park Ecological Reserve T104 Chipewyan 201F T103 Chipewyan 201G T102 T101 2888 T100 Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park T99 1661 850 Birch Mountains T98 Wildland Provincial Namur River Park 174A 33 2215 T97 94 2137 1716 T96 1060 Fort McKay 174C Namur Lake 174B 2457 239 1714 T95 21 400 965 2172 T94 ! Fort McKay 174D 1027 Fort McKay Marguerite River 2006 Wildland Provincial 879 T93 771 Park 772 2718 2926 2214 2925 T92 587 2297 2894 T91 T90 274 Whitemud Falls T89 65 !Fort McMurray Wildland Provincial Park T88 Clearwater 175 Clearwater River T87Traditional Land Provincial Park Fort McKay First Nation Gregoire Lake Provincial Park T86 Registered Fur Grand Rapids Anzac Management Area (RFMA) Wildland Provincial ! Gipsy Lake Wildland Park Provincial Park T85 Traditional Land Use Regional Study Area Gregoire Lake 176, T84 176A & 176B Traditional Land Use Local Study Area T83 ST63 ! Municipality T82 Highway Stony Mountain Township Wildland Provincial T81 Park Watercourse T80 Waterbody Cowper Lake 194A I.R. Janvier 194 T79 Wabasca 166 Provincial Park T78 National Park 0 15 30 45 T77 KILOMETRES 1:1,500,000 UTM Zone 12 NAD 83 T76 Date: 20110815 Author: CES Checked: DC File ID: 123510543-097 (Original page size: 8.5X11) Acknowledgements: Base data: AltaLIS. -

Pembina Pipeline June, 2007

Pembina Pipeline June, 2007 “Our purpose is to ensure the delivery of an excellent education to our students so they become contributing members of society.” Sharpen the saw!! Take time for yourself In Stephen Covey’s book The 7 Habits of Highly deals with how we communicate and relate with Effective People, he speaks to being proactive, one another, our empathy toward folks. putting first things first, beginning with the end in mind and other habits all leading to the 7th So with that being said, how are we getting Habit: Sharpening the Saw. ready for the summer? Did we take care of ourselves these past 10 months? I know we To those who have taken the program or read were taking the time to attend to the Alberta the book, the habit “to sharpen the saw” refers to Initiative for School Improvement, Professional allocating time to take care of our physical, Learning Communities, Assessment for spiritual, mental and social/emotional well Learning, Student Engagement, Professional being. Growth, Evaluation, Education Plans, Budgets, Annual Reports, Grade Level of Achievement, You come upon someone in the woods sawing School Superintendent Richard Harvey sharpens his saw by cutting this log with Student Services, Professional Development, down a tree. They look exhausted from working Deputy Superintendent Colleen Symyrozum- Provincial Achievement Tests, Diploma Exams for hours. You suggest they take a break to Watt at Fort Assiniboine School. and the list can go on; all related to teaching sharpen the saw. They might reply, “I don’t have and learning. time to sharpen the saw, I’m too busy sawing!” Habit 7 is taking the time to sharpen the saw. -

Woodlands County 11

Woodlands County 11 Points of Interest & Facilities 1 E.S. Huestis Demonstration Forest 2 Eagle River Casino 16 3 Whitecourt Airport 4 Forest Interpretive Centre 5 Fort Assiniboine Museum 15 12 6 World’s Largest Wagon Wheel and Pick 8 14 18 9 10 13 17 Parks, Campgrounds and Day Use Areas 1 Groat Creek Day Use Area and Group Campground 2 Eagle Creek Campground 3 Hard Luck Canyon 4 Little McLeod Lake (Carson Pegasus Provincial Park) 5 McLeod Lake (Carson Pegasus Provincial Park) 7 6 Blue Ridge Spray Park 7 Blue Ridge Recreation Area Community Halls Lookout Points 8 Goose Lake Campground 1 Westward Community Centre 1 Athabasca River Lookout 9 Goose Lake Day Use Area 2 Anselmo Community Centre 2 Coal Mine Hill Lookout 3 Blue Ridge Community Hall 10 Schuman Lake Campground and Day Use Area 4 Goose Lake Community Hall 5 Topland Community Hall Recreation Areas 11 Centre of Alberta 4 6 Fort Assiniboine Legion 1 Tubing Access (Start) 12 Freeman River RV Park 7 Timeu Community Hall 2 Tubing Take Out (Finish) 13 Mouth of the Freeman River 3 Allan & Jean Millar Centre Day Use Area 14 Woodlands RV Park 4 Blue Ridge Skating Rink Off-Highway Vehicle Areas and River Marina and Playground 1 Eagle River 15 Horse Creek Ranch Snowmobile Staging Area 5 Anselmo Skating Rink, Playground & Ball Diamond 16 Fort Assiniboine Sandhills 2 Whiteridge MX Park Wildland Provincial Park 3 Timeu Off-Highway Vehicle 6 Fort Assiniboine Skating Rink 17 Fort Assiniboine Park and Recreation Area Garter Snake Hibernaculum 4 Goat Creek Snowmoblie Staging Area 18 Fort Assiniboine Boat Launch Find out more at www.woodlands.ab.ca. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

Legislative Assembly of Alberta Title

August 26, 1996 Alberta Hansard 2391 Legislative Assembly of Alberta MR. CHADI: Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman. I feel compelled this evening to speak to the amendment as presented by Title: Monday, August 26, 1996 8:00 p.m. the Member for Fort McMurray. I think it's a great amendment. Date: 96/08/26 I listened to the debate from the Member for Fort McMurray, as head: Government Bills and Orders did the sitting Member for Athabasca-Wabasca, and I feel that this head: Committee of the Whole amendment is in keeping with what's been happening lately with [Mr. Clegg in the Chair] respect to the three names in the constituencies. I think paying tribute to Fort Chipewyan and naming Fort Bill 46 Chipewyan in the constituency name is one of the greatest things Electoral Divisions Act we could do in this Legislative Assembly. It is the oldest community in Alberta. It continues to thrive as a wonderful, THE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: We have an amendment by the thriving community. Member for Fort McMurray. In the first amendment that he moved there is a spelling error. Will the House agree that we just MR. MAGNUS: Have you been there, Sine? put a “y” in there in the spelling of Fort Chipewyan? All agreed? MR. CHADI: Many times. I've been there many, many times. HON. MEMBERS: Agreed. I can assure the hon. member who asked me if I've been there that I've spent much time in Fort Chipewyan. THE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Okay. We all agreed. There are no roads into Fort Chip, Mr. -

HARNESSING the SUPERNET ADVANTAGE • 2 • Alberta Supernet Packs Power

It’s a broadband superhighway, conceived and built by the Government of Alberta, Bell Harnessing Canada and Axia NetMedia. It links 4,200 government, health, library and learning facilities in 429 communities and brings affordable high-speed network the SuperNet access options to nearly the entire province. The Alberta SuperNet is opening the door to new economic opportuni- AdvantageAdvantage ties, expanding the borders of learning and health care, and capturing the imagination of Albertans everywhere. Here’s a look at just a few of the ways people are harnessing Alberta’s SuperNet Advantage. INTRODUCTION Zama City Fort Chipewyan Fort Vermillion Red Deer Edmonton Drumheller Calgary Medicine Hat Base network (fibre) Extended network (fibre) Manyberries Extended network (wireless) Hungry for Speed 3 Introduction Jump into a car at Zama City in the 4 Government northwest corner of Alberta and set out for Manyberries in the southeast 6 Business corner. But don’t forget to pack snacks because the journey takes 8 Health Care 19 hours. Data travels the 10 Community & Last Mile Alberta SuperNet from Zama to Manyberries in 12 Education less than 10 one-thou- sandths of a second. You 15 Looking Ahead won’t get hungry waiting. 16 Partners ILLUSTRATED ICONS BY OTTO STEININGER HARNESSING THE SUPERNET ADVANTAGE • 2 • Alberta SuperNet Packs Power You won’t see it, but it’s underfoot all across Alberta. You won’t hear it, but you might use it to see and hear someone else hundreds of kilometres away via videoconference. You can’t travel on it, but because it’s here, maybe you won’t have to travel quite as much. -

Peace-Athabasca Delta Flood Ffistory

Peace-Athabasca Delta Flood ffistory Sharon Thomson Historical Services, Prairie & Northern Region Documentary Information This research was undertaken in response to a request from Wood Buffalo National Park for information related to historic water levels on the Peace-Athabasca delta. Since 1967, when construction of the W.A. C. Bennett Dam was completed on the Peace River, water levels in both Lake Athabasca and on the delta have been low. This has allowed willow to encroach upon marshes that have historically been an important habitat for a variety of wildlife. For several years, WBNP has been examining solutions to this problem. Any reconstruction of past water levels requires an understanding of the frequency and extent of past flooding on the delta. Since water has historically been a crucial factor in transportation throughout the fur trade, it seemed probable that information on water levels would be present in daily journals kept at a number of Hudson's Bay Company trading posts Ln the vicinity of the delta. The bulk of information pertaining to Hudson's Bay Company posts is housed at the Hudson's Bay Archives in Winnipeg, and is comprised of post journals and accounts of fur returns. Information relevant to this study was derived from several different posts, with the bulk taken from daily journals kept at Fort Vermilion (covering the period 1826 to 1906) and Fort Chipewyan (covering the years 1803 to 1923). Supplementary infor.mation was obtained from post journals kept at Red River and Colvile House, from recorded fur returns for the Athabasca District, Governor George Simpson's Cortespondence Inward, and Annual District Reports. -

Archaeology in Alberta 1978

ARCHAEOLOGY IN ALBERTA, 1978 Compiled by J.M. Hillerud Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper No. 14 ~~.... Prepared by: Published by: Archaeological Survey Alberta Culture of Alberta Historical Resources Division OCCASIONAL PAPERS Papers for publication in this series of monographs are produced by or for the four branches of the Historical Resources Division of Alberta Culture: the Provincial Archives of Alberta, the Provincial Museum of Alberta, the Historic Sites Service and the Archaeological Survey of Alberta. Those persons or institutions interested in particular subject sub-series may obtain publication lists from the appropriate branches, and may purchase copies of the publications from the following address: Alberta Culture The Bookshop Provincial Museum of Alberta 12845 - 102 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5N OM6 Phone (403) 452-2150 Objectives These Occasional Papers are designed to permit the rapid dissemination of information resulting from Historical Resources' programmes. They are intended primarily for interested specialists, rather than as popular publications for general readers. In the interests of making information available quickly to these specialists, normal production procedures have been abbreviated. i ABSTRACT In 1978, the Archaeological Survey of Alberta initiated and adminis tered a number of archaeological field and laboratory investigations dealing with a variety of archaeological problems in Alberta. The ma jority of these investigations were supported by Alberta Culture. Summary reports on 21 of these projects are presented herein. An additional four "shorter contributions" present syntheses of data, and the conclusions derived from them, on selected subjects of archaeo logical interest. The reports included in this volume emphasize those investigations which have produced new contributions to the body of archaeological knowledge in the province and progress reports of con tinuing programmes of investigations. -

Fort Chipewyan Area Structure Plan

FORT CHIPEWYAN AREA STRUCTURE PLAN www.rmwb.ca/ BylawBylaw No. No. 18/005, 18/005, May May 1, 20181, 2018 1 PURPOSE The Fort Chipewyan Area Structure Plan (ASP/the Plan) is prepared in accordance with section 633 of the Municipal Government Act (MGA) and aims to: • Guide future growth in a manner that is consistent with the Municipal Development Plan (MDP); • Establish policies that promote orderly and sustainable land uses in the area; and • Integrate existing and future infrastructure requirements with proposed generalized land uses. The Plan replaces the 1991 Fort Chipewyan Area Structure Plan (Ministerial Order #464/91) as the key policy document for the next 10 years. The Plan will be reviewed every five years to ensure it remains relevant. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Plan was developed by the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo (the Municipality) with input from residents and other stakeholders. The Municipality thanks all participants, including residents and representatives from the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN), Fort Chipewyan Métis Local #125 and Mikisew Cree First Nation (MCFN) for kindly giving their time and sharing their views on making Fort Chipewyan a better place to live, work and play. Bylaw No. 18/005, May 1, 2018 2 RECOGNITION OF INDIGENOUS RIGHTS The Municipality recognizes the existing rights of Indigenous Peoples to use their traditional lands. The implementation of the Fort Chipewyan ASP is not intended to and should not be interpreted as to abrogate or derogate from Indigenous Peoples’ rights to use lands within the Plan area for traditional and cultural purposes or any consultation duties that may arise in relation to those rights. -

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities Updated December 18, 2020 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPALITIES AND THEIR COMMUNITIES MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITES Crowsnest Pass, Municipality of None Jasper, Municipality of None Lac La Biche County Beaver Lake Hamlet Hylo Hamlet Lac La Biche Hamlet Plamondon Hamlet Venice Hamlet Mackenzie County HIGH LEVEL Town RAINBOW LAKE Town Fort Vermilion Hamlet La Crete Hamlet Zama City Hamlet Strathcona County Antler Lake Hamlet Ardrossan Hamlet Collingwood Cove Hamlet Half Moon Lake Hamlet Hastings Lake Hamlet Josephburg Hamlet North Cooking Lake Hamlet Sherwood Park Hamlet South Cooking Lake Hamlet Wood Buffalo, Regional Municipality of Anzac Hamlet Conklin Hamlet Fort Chipewyan Hamlet Fort MacKay Hamlet Fort McMurray Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 1 of 25 Gregoire Lake Estates Hamlet Janvier South Hamlet Saprae Creek Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 2 of 25 MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS Acadia No. 34, M.D. of Acadia Valley Hamlet Athabasca County ATHABASCA Town BOYLE Village BONDISS Summer Village ISLAND LAKE SOUTH Summer Village ISLAND LAKE Summer Village MEWATHA BEACH Summer Village SOUTH BAPTISTE Summer Village SUNSET BEACH Summer Village WEST BAPTISTE Summer Village WHISPERING HILLS Summer Village Atmore Hamlet Breynat Hamlet Caslan Hamlet Colinton Hamlet -

Roadside Management Classification

I.R. I.R. 196A I.R. 196G 196D I.R. 225 I.R. I.R. I.R. 196B 196 196C I.R. 196F I.R. 196E I.R. 223 WOOD BUFFALO NATIONAL PARK I.R. Colin-Cornwall Lakes I.R. 224 Wildland 196H Provincial Park I.R. 196I La Butte Creek Wildland P. Park Ca ribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Fidler-Greywillow Wildland P. Park I.R. 222 I.R. 221 I.R. I.R. 219 Fidler-Greywillow 220 Wildland P. Park Fort Chipewyan I.R. 218 58 I.R. 5 I.R. I.R. 207 8 163B 201A I.R . I.R. I.R. 201B 164A I.R. 215 163A I.R. WOOD BU I.R. 164 FFALO NATIONAL PARK 201 I.R Fo . I.R. 162 rt Vermilion 163 I.R. 173B I.R. 201C I.R. I.R. 201D 217 I.R. 201E 697 La Crete Maybelle Wildland P. Park Richardson River 697 Dunes Wildland I.R. P. Park 173A I.R. 201F 88 I.R. 173 87 I.R. 201G I.R. 173C Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park I.R. 174A I.R. I.R. 174B 174C Marguerite River Wildland I.R. Provincial Park 174D Fort MacKay I.R. 174 88 63 I.R. 237 686 Whitemud Falls Wildland FORT Provincial Park McMURRAY 686 Saprae Creek I.R. 226 686 I.R. I.R 686 I.R. 227 I.R. 228 235 Red Earth 175 Cre Grand Rapids ek Wildland Provincial Park Gipsy Lake I.R. Wildland 986 238 986 Cadotte Grand Rapids Provincial Park Lake Wildland Gregoire Lake Little Buffalo Provincial Park P. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage,