Pseudo-Learning Effects in Reinforcement Learning Model-Based Analysis: a Problem Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 4 Feedforward Neural Networks, Backpropagation

CS7015 (Deep Learning): Lecture 4 Feedforward Neural Networks, Backpropagation Mitesh M. Khapra Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Madras 1/9 Mitesh M. Khapra CS7015 (Deep Learning): Lecture 4 References/Acknowledgments See the excellent videos by Hugo Larochelle on Backpropagation 2/9 Mitesh M. Khapra CS7015 (Deep Learning): Lecture 4 Module 4.1: Feedforward Neural Networks (a.k.a. multilayered network of neurons) 3/9 Mitesh M. Khapra CS7015 (Deep Learning): Lecture 4 The input to the network is an n-dimensional hL =y ^ = f(x) vector The network contains L − 1 hidden layers (2, in a3 this case) having n neurons each W3 b Finally, there is one output layer containing k h 3 2 neurons (say, corresponding to k classes) Each neuron in the hidden layer and output layer a2 can be split into two parts : pre-activation and W 2 b2 activation (ai and hi are vectors) h1 The input layer can be called the 0-th layer and the output layer can be called the (L)-th layer a1 W 2 n×n and b 2 n are the weight and bias W i R i R 1 b1 between layers i − 1 and i (0 < i < L) W 2 n×k and b 2 k are the weight and bias x1 x2 xn L R L R between the last hidden layer and the output layer (L = 3 in this case) 4/9 Mitesh M. Khapra CS7015 (Deep Learning): Lecture 4 hL =y ^ = f(x) The pre-activation at layer i is given by ai(x) = bi + Wihi−1(x) a3 W3 b3 The activation at layer i is given by h2 hi(x) = g(ai(x)) a2 W where g is called the activation function (for 2 b2 h1 example, logistic, tanh, linear, etc.) The activation at the output layer is given by a1 f(x) = h (x) = O(a (x)) W L L 1 b1 where O is the output activation function (for x1 x2 xn example, softmax, linear, etc.) To simplify notation we will refer to ai(x) as ai and hi(x) as hi 5/9 Mitesh M. -

Revisiting the Softmax Bellman Operator: New Benefits and New Perspective

Revisiting the Softmax Bellman Operator: New Benefits and New Perspective Zhao Song 1 * Ronald E. Parr 1 Lawrence Carin 1 Abstract tivates the use of exploratory and potentially sub-optimal actions during learning, and one commonly-used strategy The impact of softmax on the value function itself is to add randomness by replacing the max function with in reinforcement learning (RL) is often viewed as the softmax function, as in Boltzmann exploration (Sutton problematic because it leads to sub-optimal value & Barto, 1998). Furthermore, the softmax function is a (or Q) functions and interferes with the contrac- differentiable approximation to the max function, and hence tion properties of the Bellman operator. Surpris- can facilitate analysis (Reverdy & Leonard, 2016). ingly, despite these concerns, and independent of its effect on exploration, the softmax Bellman The beneficial properties of the softmax Bellman opera- operator when combined with Deep Q-learning, tor are in contrast to its potentially negative effect on the leads to Q-functions with superior policies in prac- accuracy of the resulting value or Q-functions. For exam- tice, even outperforming its double Q-learning ple, it has been demonstrated that the softmax Bellman counterpart. To better understand how and why operator is not a contraction, for certain temperature pa- this occurs, we revisit theoretical properties of the rameters (Littman, 1996, Page 205). Given this, one might softmax Bellman operator, and prove that (i) it expect that the convenient properties of the softmax Bell- converges to the standard Bellman operator expo- man operator would come at the expense of the accuracy nentially fast in the inverse temperature parameter, of the resulting value or Q-functions, or the quality of the and (ii) the distance of its Q function from the resulting policies. -

On the Learning Property of Logistic and Softmax Losses for Deep Neural Networks

The Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-20) On the Learning Property of Logistic and Softmax Losses for Deep Neural Networks Xiangrui Li, Xin Li, Deng Pan, Dongxiao Zhu∗ Department of Computer Science Wayne State University {xiangruili, xinlee, pan.deng, dzhu}@wayne.edu Abstract (unweighted) loss, resulting in performance degradation Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained with lo- for minority classes. To remedy this issue, the class-wise gistic and softmax losses have made significant advancement reweighted loss is often used to emphasize the minority in visual recognition tasks in computer vision. When training classes that can boost the predictive performance without data exhibit class imbalances, the class-wise reweighted ver- introducing much additional difficulty in model training sion of logistic and softmax losses are often used to boost per- (Cui et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2016; Mahajan et al. 2018; formance of the unweighted version. In this paper, motivated Wang, Ramanan, and Hebert 2017). A typical choice of to explain the reweighting mechanism, we explicate the learn- weights for each class is the inverse-class frequency. ing property of those two loss functions by analyzing the nec- essary condition (e.g., gradient equals to zero) after training A natural question then to ask is what roles are those CNNs to converge to a local minimum. The analysis imme- class-wise weights playing in CNN training using LGL diately provides us explanations for understanding (1) quan- or SML that lead to performance gain? Intuitively, those titative effects of the class-wise reweighting mechanism: de- weights make tradeoffs on the predictive performance terministic effectiveness for binary classification using logis- among different classes. -

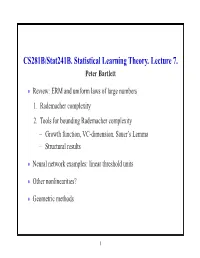

CS281B/Stat241b. Statistical Learning Theory. Lecture 7. Peter Bartlett

CS281B/Stat241B. Statistical Learning Theory. Lecture 7. Peter Bartlett Review: ERM and uniform laws of large numbers • 1. Rademacher complexity 2. Tools for bounding Rademacher complexity Growth function, VC-dimension, Sauer’s Lemma − Structural results − Neural network examples: linear threshold units • Other nonlinearities? • Geometric methods • 1 ERM and uniform laws of large numbers Empirical risk minimization: Choose fn F to minimize Rˆ(f). ∈ How does R(fn) behave? ∗ For f = arg minf∈F R(f), ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ R(fn) R(f )= R(fn) Rˆ(fn) + Rˆ(fn) Rˆ(f ) + Rˆ(f ) R(f ) − − − − ∗ ULLN for F ≤ 0 for ERM LLN for f |sup R{z(f) Rˆ}(f)| + O(1{z/√n).} | {z } ≤ f∈F − 2 Uniform laws and Rademacher complexity Definition: The Rademacher complexity of F is E Rn F , k k where the empirical process Rn is defined as n 1 R (f)= ǫ f(X ), n n i i i=1 X and the ǫ1,...,ǫn are Rademacher random variables: i.i.d. uni- form on 1 . {± } 3 Uniform laws and Rademacher complexity Theorem: For any F [0, 1]X , ⊂ 1 E Rn F O 1/n E P Pn F 2E Rn F , 2 k k − ≤ k − k ≤ k k p and, with probability at least 1 2exp( 2ǫ2n), − − E P Pn F ǫ P Pn F E P Pn F + ǫ. k − k − ≤ k − k ≤ k − k Thus, P Pn F E Rn F , and k − k ≈ k k R(fn) inf R(f)= O (E Rn F ) . − f∈F k k 4 Tools for controlling Rademacher complexity 1. -

Loss Function Search for Face Recognition

Loss Function Search for Face Recognition Xiaobo Wang * 1 Shuo Wang * 1 Cheng Chi 2 Shifeng Zhang 2 Tao Mei 1 Abstract Generally, the CNNs are equipped with classification loss In face recognition, designing margin-based (e.g., functions (Liu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018f;e; 2019a; Yao angular, additive, additive angular margins) soft- et al., 2018; 2017; Guo et al., 2020), metric learning loss max loss functions plays an important role in functions (Sun et al., 2014; Schroff et al., 2015) or both learning discriminative features. However, these (Sun et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2018b). hand-crafted heuristic methods are sub-optimal Metric learning loss functions such as contrastive loss (Sun because they require much effort to explore the et al., 2014) or triplet loss (Schroff et al., 2015) usually large design space. Recently, an AutoML for loss suffer from high computational cost. To avoid this problem, function search method AM-LFS has been de- they require well-designed sample mining strategies. So rived, which leverages reinforcement learning to the performance is very sensitive to these strategies. In- search loss functions during the training process. creasingly more researchers shift their attention to construct But its search space is complex and unstable that deep face recognition models by re-designing the classical hindering its superiority. In this paper, we first an- classification loss functions. alyze that the key to enhance the feature discrim- Intuitively, face features are discriminative if their intra- ination is actually how to reduce the softmax class compactness and inter-class separability are well max- probability. -

Deep Neural Networks for Choice Analysis: Architecture Design with Alternative-Specific Utility Functions Shenhao Wang Baichuan

Deep Neural Networks for Choice Analysis: Architecture Design with Alternative-Specific Utility Functions Shenhao Wang Baichuan Mo Jinhua Zhao Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Whereas deep neural network (DNN) is increasingly applied to choice analysis, it is challenging to reconcile domain-specific behavioral knowledge with generic-purpose DNN, to improve DNN's interpretability and predictive power, and to identify effective regularization methods for specific tasks. To address these challenges, this study demonstrates the use of behavioral knowledge for designing a particular DNN architecture with alternative-specific utility functions (ASU-DNN) and thereby improving both the predictive power and interpretability. Unlike a fully connected DNN (F-DNN), which computes the utility value of an alternative k by using the attributes of all the alternatives, ASU-DNN computes it by using only k's own attributes. Theoretically, ASU- DNN can substantially reduce the estimation error of F-DNN because of its lighter architecture and sparser connectivity, although the constraint of alternative-specific utility can cause ASU- DNN to exhibit a larger approximation error. Empirically, ASU-DNN has 2-3% higher prediction accuracy than F-DNN over the whole hyperparameter space in a private dataset collected in Singapore and a public dataset available in the R mlogit package. The alternative-specific connectivity is associated with the independence of irrelevant alternative (IIA) constraint, which as a domain-knowledge-based regularization method is more effective than the most popular generic-purpose explicit and implicit regularization methods and architectural hyperparameters. ASU-DNN provides a more regular substitution pattern of travel mode choices than F-DNN does, rendering ASU-DNN more interpretable. -

Lecture 18: Wrapping up Classification Mark Hasegawa-Johnson, 3/9/2019

Lecture 18: Wrapping up classification Mark Hasegawa-Johnson, 3/9/2019. CC-BY 3.0: You are free to share and adapt these slides if you cite the original. Modified by Julia Hockenmaier Today’s class • Perceptron: binary and multiclass case • Getting a distribution over class labels: one-hot output and softmax • Differentiable perceptrons: binary and multiclass case • Cross-entropy loss Recap: Classification, linear classifiers 3 Classification as a supervised learning task • Classification tasks: Label data points x ∈ X from an n-dimensional vector space with discrete categories (classes) y ∈Y Binary classification: Two possible labels Y = {0,1} or Y = {-1,+1} Multiclass classification: k possible labels Y = {1, 2, …, k} • Classifier: a function X →Y f(x) = y • Linear classifiers f(x) = sgn(wx) [for binary classification] are parametrized by (n+1)-dimensional weight vectors • Supervised learning: Learn the parameters of the classifier (e.g. w) from a labeled data set Dtrain = {(x1, y1),…,(xD, yD)} Batch versus online training Batch learning: The learner sees the complete training data, and only changes its hypothesis when it has seen the entire training data set. Online training: The learner sees the training data one example at a time, and can change its hypothesis with every new example Compromise: Minibatch learning (commonly used in practice) The learner sees small sets of training examples at a time, and changes its hypothesis with every such minibatch of examples For minibatch and online example: randomize the order of examples for -

Categorical Data

Categorical Data Santiago Barreda LSA Summer Institute 2019 Normally-distributed data • We have been modelling data with normally-distributed residuals. • In other words: the data is normally- distributed around the mean predicted by the model. Predicting Position by Height • We will invert the questions we’ve been considering. • Can we predict position from player characteristics? Using an OLS Regression Using an OLS Regression Using an OLS Regression • Not bad but we can do better. In particular: • There are hard bounds on our outcome variable. • The boundaries affect possible errors: i.e., the 1 position cannot be underestimated but the 2 can. • There is nothing ‘between’ the outcomes. • There are specialized models for data with these sorts of characteristics. The Generalized Linear Model • We can break up a regression model into three components: • The systematic component. • The random component. • The link function. 푦 = 푎 + 훽 ∗ 푥 + 푒 The Systematic Component • This is our regression equation. • It specifies a deterministic relationship between the predictors and the predicted value. • In the absence of noise and with the correct model, we would expect perfect prediction. μ = 푎 + 훽 ∗ 푥 Predicted value. Not the observation. The Random Component • Unpredictable variation conditional on the fitted value. • This specifies the nature of that variation. • The fitted value is the mean parameter of a probability distribution. μ = 푎 + 훽 ∗ 푥 푦~푁표푟푚푎푙(휇, 휎2) 푦~퐵푒푟푛표푢푙푙(휇) Bernoulli Distribution • Unlike the normal, this distribution generates only values of 1 and 0. • It has only a single parameter, which must be between 0 and 1. • The parameter is the probability of observing an outcome of 1 (or 1-P of 0). -

Mixed Pattern Recognition Methodology on Wafer Maps with Pre-Trained Convolutional Neural Networks

Mixed Pattern Recognition Methodology on Wafer Maps with Pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks Yunseon Byun and Jun-Geol Baek School of Industrial Management Engineering, Korea University, Seoul, South Korea {yun-seon, jungeol}@korea.ac.kr Keywords: Classification, Convolutional Neural Networks, Deep Learning, Smart Manufacturing. Abstract: In the semiconductor industry, the defect patterns on wafer bin map are related to yield degradation. Most companies control the manufacturing processes which occur to any critical defects by identifying the maps so that it is important to classify the patterns accurately. The engineers inspect the maps directly. However, it is difficult to check many wafers one by one because of the increasing demand for semiconductors. Although many studies on automatic classification have been conducted, it is still hard to classify when two or more patterns are mixed on the same map. In this study, we propose an automatic classifier that identifies whether it is a single pattern or a mixed pattern and shows what types are mixed. Convolutional neural networks are used for the classification model, and convolutional autoencoder is used for initializing the convolutional neural networks. After trained with single-type defect map data, the model is tested on single-type or mixed- type patterns. At this time, it is determined whether it is a mixed-type pattern by calculating the probability that the model assigns to each class and the threshold. The proposed method is experimented using wafer bin map data with eight defect patterns. The results show that single defect pattern maps and mixed-type defect pattern maps are identified accurately without prior knowledge. -

![Arxiv:1910.04465V2 [Cs.CV] 16 Oct 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1199/arxiv-1910-04465v2-cs-cv-16-oct-2019-1151199.webp)

Arxiv:1910.04465V2 [Cs.CV] 16 Oct 2019

Searching for A Robust Neural Architecture in Four GPU Hours Xuanyi Dong1;2,Yi Yang1 1University of Technology Sydney 2Baidu Research [email protected], [email protected] Abstract 0 0 : input GDAS Conventional neural architecture search (NAS) ap- 3 : output on a DAG proaches are based on reinforcement learning or evolution- : sampled ary strategy, which take more than 3000 GPU hours to find : unsampled a good model on CIFAR-10. We propose an efficient NAS 1 approach learning to search by gradient descent. Our ap- proach represents the search space as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). This DAG contains billions of sub-graphs, each of which indicates a kind of neural architecture. To 2 avoid traversing all the possibilities of the sub-graphs, we develop a differentiable sampler over the DAG. This sam- pler is learnable and optimized by the validation loss af- ter training the sampled architecture. In this way, our ap- proach can be trained in an end-to-end fashion by gra- 3 dient descent, named Gradient-based search using Differ- entiable Architecture Sampler (GDAS). In experiments, we Figure 1. We utilize a DAG to represent the search space of a neu- can finish one searching procedure in four GPU hours on ral cell. Different operations (colored arrows) transform one node CIFAR-10, and the discovered model obtains a test error (square) to its intermediate features (little circles). Meanwhile, of 2.82% with only 2.5M parameters, which is on par with each node is the sum of the intermediate features transformed from the state-of-the-art. -

Reinforcement Learning with Dynamic Boltzmann Softmax Updates Arxiv

Reinforcement Learning with Dynamic Boltzmann Softmax Updates Ling Pan1, Qingpeng Cai1, Qi Meng2, Wei Chen2, Longbo Huang1, Tie-Yan Liu2 1IIIS, Tsinghua University 2Microsoft Research Asia Abstract Value function estimation is an important task in reinforcement learning, i.e., prediction. The Boltz- mann softmax operator is a natural value estimator and can provide several benefits. However, it does not satisfy the non-expansion property, and its direct use may fail to converge even in value iteration. In this paper, we propose to update the value function with dynamic Boltzmann softmax (DBS) operator, which has good convergence property in the setting of planning and learning. Experimental results on GridWorld show that the DBS operator enables better estimation of the value function, which rectifies the convergence issue of the softmax operator. Finally, we propose the DBS-DQN algorithm by applying dynamic Boltzmann softmax updates in deep Q-network, which outperforms DQN substantially in 40 out of 49 Atari games. 1 Introduction Reinforcement learning has achieved groundbreaking success for many decision making problems, including roboticsKober et al. (2013), game playingMnih et al. (2015); Silver et al. (2017), and many others. Without full information of transition dynamics and reward functions of the environment, the agent learns an optimal policy by interacting with the environment from experience. Value function estimation is an important task in reinforcement learning, i.e., prediction Sutton (1988); DEramo et al. (2016); Xu et al. (2018). In the prediction task, it requires the agent to have a good estimate of the value function in order to update towards the true value function. -

Rethinking Feature Distribution for Loss Functions in Image Classification

Rethinking Feature Distribution for Loss Functions in Image Classification Weitao Wan1∗ Yuanyi Zhong1,2∗† Tianpeng Li1 Jiansheng Chen1‡ 1Department of Electronic Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 2Department of Computer Science, University of at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract and the class label is used as the loss function. The soft- max loss has its probabilistic interpretation in that, for a We propose a large-margin Gaussian Mixture (L-GM) large class of distributions, the posterior distribution com- loss for deep neural networks in classification tasks. Dif- plies with the softmax transformation of linear functions of ferent from the softmax cross-entropy loss, our proposal the feature vectors [1]. It can also be derived from a binary is established on the assumption that the deep features of Markov Random Field or a Boltzmann Machine model [3]. the training set follow a Gaussian Mixture distribution. By However, the relationship between the affinity score and the involving a classification margin and a likelihood regular- probability distribution of the training feature space is vague. ization, the L-GM loss facilitates both a high classification In other words, for an extracted feature, its likelihood to the performance and an accurate modeling of the training fea- training feature distribution is not well formulated. ture distribution. As such, the L-GM loss is superior to the Several variants have been proposed to enhance the ef- softmax loss and its major variants in the sense that besides fectiveness of the softmax loss.