The Winter's Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma As Drama in the Tempest Jeffrey R

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma as Drama in The Tempest Jeffrey R. Wilson The dramatis personae of The Tempest casts Caliban as “asavageand deformed slave.”1 Since the mid-twentieth century, critics have scrutinized Caliban’s status as a “slave,” developing a riveting post-colonial reading of the play, but I want to address the pairing of “savage and deformed.”2 If not Shakespeare’s own mixture of moral and corporeal abominations, “savage and deformed” is the first editorial comment on Caliban, the “and” here Stigmatized as such, Caliban’s body never comes to us .”ס“ working as an uninterpreted. It is always already laden with meaning. But what, if we try to strip away meaning from fact, does Caliban actually look like? The ambiguous and therefore amorphous nature of Caliban’s deformity has been a perennial problem in both dramaturgical and critical studies of The Tempest at least since George Steevens’s edition of the play (1793), acutely since Alden and Virginia Vaughan’s Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural His- tory (1993), and enduringly in recent readings by Paul Franssen, Julia Lup- ton, and Mark Burnett.3 Of all the “deformed” images that actors, artists, and critics have assigned to Caliban, four stand out as the most popular: the devil, the monster, the humanoid, and the racial other. First, thanks to Prospero’s yarn of a “demi-devil” (5.1.272) or a “born devil” (4.1.188) that was “got by the devil himself” (1.2.319), early critics like John Dryden and Joseph War- ton envisioned a demonic Caliban.4 In a second set of images, the reverbera- tions of “monster” in The Tempest have led writers and artists to envision Caliban as one of three prodigies: an earth creature, a fish-like thing, or an animal-headed man. -

Caliban's Use of Language in Shakespeare's the Tempest

fi4 Notions Vol.6 No3 2015 (P) ISSN t 097G5247, (epSSN: 239*7239 Caliban's Use of Language in Shakespearers The Tbmpest You taught me language, and my profit on,t Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you For learning me your language! (Act I, Scene II, The Tempest) ..The Richard Eyre, a distinguished English director said, life of the plays is in the language, not alongside ig or underneath i1. f'sslings and thoughts are released at the moment of speech. An Elizabethan audience would have responded to the pulse, the rhythms, the shapes, sounds, and above all meanings, within the consistent ten- syllable, five- stress lines of blank verse. They were an audience who listened,,. (Shakespeareb Language 4) At the outset, the audience has to make a distinction between some modern connotations ofthe word 'language, and those current in Shakespeare's day, when language was neither neutal nor purely verbal. A neutral view of language is typified by such statements as Saussure,s remark: From the excursions made into regions bordering upon linguistics, there emerges a negative lesson, but one which...supports the fundamental thesis of this course: the only true object of study in linguistics is the language, considered in itself and for its own sake. (Course inGeneral Linguistics) Such an empirical approachwas alientothe sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, where all concems of life were moralizod, including language, in so far as most writers looked for ways of integrating their subject with the current dominant Christian concepts. Language and knowledge has been the key to power on the island in the play. -

And Margaret Atwood's Novel Hag-Seed

The textual conversation between William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest (1611) and Margaret Atwood’s novel Hag-Seed (2016) positions readers to realise how individuals must move on from the past in order to achieve fulfilment. Readers recognise how introspection and accepting the past is necessary in order to reconcile with loss and how to achieve freedom, individuals must overcome their restrictive, seemingly predestined capacities. Atwood’s appropriation of The Tempest allows contemporary audiences to gain true insight into the timeless values of self-reflection, reconciliation and challenging one’s destiny. The textual conversation between The Tempest and Hag-Seed facilitates readers’ appreciation of how introspection and accepting the past is necessary in order to reconcile with loss. In The Tempest, Shakespeare advocates how Prospero’s introspection as he moves on from his preoccupation with revenge, prompts compassion and forgiveness. Shakespeare responds to the rise of Renaissance Humanism during the Jacobean Era, celebrating human control over one’s fate and display of virtues such as empathy and self-enquiry. Shakespeare characterises exiled Duke of Milan Prospero as unwilling to acknowledge how his usurpation by his brother Antonio resulted from preoccupations with magic as he accuses Antonio of being the metaphorical "ivy which had hid my princely trunk” to emphasise his loss and victimise himself. Shakespeare establishes Prospero’s anger towards his past betrayal in the supernatural stage directions [Enter several strange shapes, bringing in a banquet…] and [...the banquet vanishes], revealing how he uses magic to humiliate and punish the shipwrecked Royal Court. However, Shakespeare exposes how Prospero’s belief that revenge is justified is challenged by spirit Ariel in “if you now beheld them, your affections would become tender…. -

“From Strange to Stranger”: the Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage

“From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English and the Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Professor Oliver Arnold Professor David Landreth Professor Timothy Hampton Summer 2018 “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage © 2018 by Aileen Young Liu 1 Abstract “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu Doctor of Philosophy in English Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Long scorned for their strange inconsistencies and implausibilities, Shakespeare’s romance plays have enjoyed a robust critical reconsideration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But in the course of reclaiming Pericles, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, and The Tempest as significant works of art, this revisionary critical tradition has effaced the very qualities that make these plays so important to our understanding of Shakespeare’s career and to the development of English Renaissance drama: their belatedness and their overt strangeness. While Shakespeare’s earlier plays take pains to integrate and subsume their narrative romance sources into dramatic form, his late romance plays take exactly the opposite approach: they foreground, even exacerbate, the tension between romance and drama. Verisimilitude is a challenge endemic to theater as an embodied medium, but Shakespeare’s romance plays brazenly alert their audiences to the incredible. -

A Jungian Interpretation of the Tempest

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1978 A Jungian interpretation of The Tempest Tana Smith University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Tana. (1978). A Jungian interpretation of The Tempest. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/1989 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A JUNGil-..~~ INTERPllliTATION OF THE 'rEHPES'r by Tana Smit!1 An Essay Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Univers ity of the Pac ific In Pa rtial Fulfillment of the Requireme nts for the Degree Maste r of Arts Hay 1978 The following psychological interpretation of Shakespeare's 1 The Tempest is unique to articles on the ·same subject which have appeared in literary journals because it applies a purely Jungian reading to the characters in the play. Here each character is shown to represent one of the archetypes which Jung described in his book Archetypes ~ the Collective Unconscious. In giving the play a psychological interpretation, the action must be seen to occur inside Prospera's own unconscious mind. He is experiencing a psychic transformation or what Jung called the individuation process, where a person becomes "a separate, indivisible unity or 2 whole" and where the conscious and unconscious are united. -

Kings of Their Castles: Reading Heathcliff As a Caliban Who Succeeds

KINGS OF THEIR CASTLES: READING HEATHCLIFF AS A CALIBAN WHO SUCCEEDS by ELIZABETH KOZINSKY (Under the direction of Christy Desmet) ABSTRACT At first othered by his text and then given the power to marginalize the next generation, Heathcliff provides a vision of what a Caliban who succeeds would be and further explores the idea of a family producing its own outsider. Highlighting the cyclical nature of both texts, Kozinsky analyzes Heathcliff and Caliban’s shared kinship with the Medieval Wild Man to explain the varying reactions to them. She also considers Heathcliff’s affinity to the mastermind Prospero and their relationship to the tradition of revenge tragedy. By considering both the structural similarities of Shakespeare's play against Brontë's novel and the varying interpretations of both for a nineteenth century audience, a better sense of these characters emerges, why we fear and are fascinated by them. INDEX WORDS: Heathcliff, Caliban, Wild Man, revenge, Other, Emily Brontë, Shakespeare, alterity, Wuthering Heights, Tempest, Prospero, Byron, natural man, appropriation KINGS OF THEIR CASTLES: READING HEATHCLIFF AS A CALIBAN WHO SUCCEEDS by ELIZABETH KOZINSKY BA, University of Georgia, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Elizabeth Kozinsky All Rights Reserved KINGS OF THEIR CASTLES: READING HEATHCLIFF AS A CALIBAN WHO SUCCEEDS by ELIZABETH KOZINSKY Major Professor: Christy Desmet Committee: Richard Menke Roxanne Eberle Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2010 DEDICATION Ths work is dedicated to Fran Teague, who long ago recognized and embraced me as an Other, and to Ben Teague, who was himself a magician on the stage. -

Olympos Epub Downloads

Olympos Epub Downloads Beneath the gaze of the gods, the mighty armies of Greece and Troy met in fierce and glorious combat, scrupulously following the text set forth in Homer's timeless narrative. But that was before twenty-first-century scholar Thomas Hockenberry stirred the bloody brew, causing an enraged Achilles to join forces with his archenemy Hector and turn his murderous wrath on Zeus and the entire pantheon of divine manipulators; before the swift and terrible mechanical creatures that catered for centuries to the pitiful idle remnants of Earth's human race began massing in the millions, to exterminate rather than serve.And now all bets are off. Audio CD Publisher: Brilliance Audio; Unabridged edition (August 12, 2014) Language: English ISBN-10: 1480591734 ISBN-13: 978-1480591738 Product Dimensions: 6.5 x 2.2 x 5.5 inches Shipping Weight: 1.4 pounds (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.0 out of 5 stars 229 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #4,202,477 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #15 in Books > Books on CD > Authors, A-Z > ( S ) > Simmons, Dan #2767 in Books > Books on CD > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction #3284 in Books > Books on CD > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Fantasy Welcome back to the Trojan War gone round the bend. Hector and Achilles have joined forces against the Olympic Gods. Back on a future Earth, assorted creatures from Shakespeare's The Tempest get ready to rumble in a winner-takes-the-universe battle royale. And amid it all, a group of confused mere mortals with their classically trained robot allies (from Jupiter no less) race across time and space to keep from getting squashed as the various Titans of the Western Canon square off. -

Year 7 Home Learning the Tempest by William Shakespeare Weeks 1-3

Year 7 Home Learning The Tempest by William Shakespeare Weeks 1-3 Name: __________________ Rastrick High School How to use this booklet: During the third half term of Year 7 we will study The Tempest by William Shakespeare. If you are working from home at any point during this time, you should use this booklet to complete your home learning. This booklet will break down the reading and writing into week by week sections with tasks to complete. If you have been in school for part of the time but are now studying from home, you should start the lessons from where you last finished with your class teacher. Summary of the scheme The Tempest is a six-week scheme of work that continues on from your work on Shakespeare’s World. Throughout this scheme, you will study: - Key moments from the play - Key historical information relevant to the ideas in the play - Some of Shakespeare’s use of language to present characters and relationships. - The theme of power, control, supernatural and society. The main focus, throughout your study of the play, is the central character Prospero. As you work through, pay close attention to your impression of Prospero and how it might change as the play develops. All extracts from the play can be found at the back of the booklet. Support: Discussing a text At some points you will be asked to write a What? How? Why? Paragraph. The section below provides some advice on how to write this. What is the writer doing? The first sentence of your paragraph should clearly explain what the writer is doing. -

Shakespeare's Romance of Knowing

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 11 1988 Shakespeare's Romance of Knowing Maurice Hunt Baylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hunt, Maurice (1988) "Shakespeare's Romance of Knowing," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) Shakespeare's Romance of Knowing by Maurice Hunt Baylor University From time to time literary cnucs have claimed that Shakespeare's undisputed last plays-Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale, and The Tempest-are, to varying degrees, concerned with the main characters' learning experiences. These claims range, for example, from Stephen Orgel's argument that adver• sity schools Alonso and Prospero in humility to Northrop Frye's assertion that education provides the means for the protagonists of the last plays to recover some sort of paradise. 1 In other words, critics over the years have claimed in different ways that the last plays are either educational or epistemological romances. And yet no one, to my knowledge, has tried to explain why Shakespeare was inclined to make dramatic romance so especially concerned with various and complex ways of knowing. In this essay I argue that Shakespeare, in his last plays, established a kind of play-a "romance of knowing"-previously not seen in a fully articulated form on either the Elizabethan or the Jacobean stage. -

From France James Thierrée's

FROM FRANCE JAMES THIERRÉE’S CHICAGO SHAKESPEARE THEATER About CST Welcome A global theatrical force, Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST) is known for vibrant productions that reflect Shakespeare’s genius for storytelling, musicality of language, and empathy for the human condition. Under the leadership of Artistic Director Barbara Gaines and Executive Director Criss Henderson, Chicago Shakespeare has redefined what a great American Shakespeare theater can be—a company that, delighting in the unexpected, defies theatrical category. A Regional Tony Award-winning theater, CST stages acclaimed plays at its home on Navy Pier, throughout Chicago’s schools and neighborhoods, and on stages around the world. In 2017, the Theater unveils The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, with an innovative design that will change the shape of theater-making. Together with the Jentes Family Courtyard Theater and the Thoma Theater Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare, DEAR FRIENDS, The Yard positions CST as the city’s largest and most versatile performing arts Welcome to The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare! We are proud to introduce to venue. Chicago a new theater, as forward-thinking and responsive as our artistic spirit. Chicago Shakespeare’s year-round season features as many as twenty productions The versatility of the space means that it is perfectly suited to our wide range of and 650 performances—including plays, musicals, world premieres, and visiting work: from large-scale musicals and new commissions, to international imports and international presentations—to engage a broad, multigenerational audience of programs for young audiences, and, of course, bold imaginings of Shakespeare’s 225,000 community members. Recognized in 2014 in a White House ceremony plays and other classics. -

Vindicating Sycorax's Anti-Colonial Voice. an Overview of Some

VINDICATING SYCORAX’S ANTI-COLONIAL VOICE. AN OVERVIEW OF SOME POSTCOLONIAL RE-WRITINGS FROM THE TEMPEST TO INDIGO XIANA VÁZQUEZ BOUZÓ Universidade de Vigo The aim of this essay is to place the Shakespearean character Sycorax as a symbol of anti- colonial and anti-patriarchal resistance. Throughout the analysis of this figure in The Tempest and its re-writings, I suggest a change from the theories that turned Caliban into an antiim- perial symbol towards a consideration of Sycorax for this role. I analyse the possibilities that this character opens in terms of re-writing, as well as the relation of the figure of the witch with her community. I also compare the ideas that Caliban personifies (including sexual violence), with those represented by Sycorax (the struggle against imperial and patriarchal forces). I ultimately defend that Sycorax fits better the position as a resistance symbol, since the strug- gles against masculine dominance must be addressed at the same level as those against imperi- alist oppressions. KEY WORDS : The Tempest , Sycorax, Indigo , anti-colonialism, anti-patriarchy. Reivindicación de la voz anti-colonial de Sycorax. Estudio de algunas reescrituras postcolo- niales desde The Tempest hasta Indigo El objetivo de este ensayo es proponer al personaje shakespeariano Sycorax como símbolo de resistencia anticolonial y antipatriarcal. A través del análisis de esta figura en The Tempest y sus reescrituras, sugiero un cambio desde las teorías que convirtieron a Caliban en un símbolo antiimperialista hacia una nueva consideración de Sycorax para este papel. Analizo las posibili- dades que este personaje abre en términos de reescritura, así como la relación entre la figura de la bruja y su comunidad. -

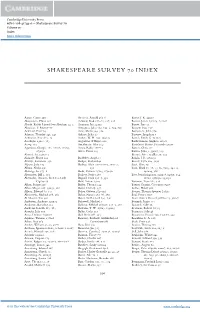

Shakespeare Survey 70 Index

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41744-0 — Shakespeare Survey 70 Volume 70 Index More Information SHAKESPEARE SURVEY 70 INDEX Aaron, Catrin 307 Aronson, Arnold 365–6 Barret, J. K. 230n7 Abeysekera, Hiran 302 Ashford, Rob 311–12, 337, 338 Barrett, James 150n14, 152n21 Aboab, Rabbi Samuel ben Abraham 74–5 Assmann, Jan 259n2 Barritt, Ian 313 Abraham, F. Murray 77 Astington, John 189, 192–3, 194, 196 Barrow, Isaac 127 Ackroyd, Peter 64 Atim, Sheila 309, 310 Barrymore, John 370 Adorno, Theodor 241, 247 Aubrey, John 59 Barstow, Josephine 7 Aebischer, Pascal 13, 14 Auden, W. H. 200, 204n29 Bartels, Emily C. 153n23 Aeschylus 150–3, 387 Augustine of Hippo 222 Bartholomeus Anglicus 207–8 Aesop 165 Ayckbourn, Alan 369 Bartolomé Benito, Fernando 97n38 Agamben, Giorgio 213, 272n1, 273n9, Ayola, Rakie 318–19 Barton, Chris 331 275n32 Ayres, Fraser 319 Barton, John 3, 55n18, 339 Ahmed, Sara 231n15 Basauri, Aitor 324Illus.30, 324 Akinade, Fisayo 291 Baddeley, Angela 3 Baskin, J. R. 281n59 Akitaya, Kazunori 356 Badger, Richard 42 Bassett, Lytta 224–5n31 Alberts, Jada 320 Badiou, Alain 272–3n1–5, 275n33, Bassi, Gino 70 Albina, Nadia 296 276 Bassi, Shaul 67–78, 79, 80, 82n5, 241–2, Aldridge, Ira 375–6 Badir, Patricia 137n4, 279n50 246n29, 386 Alexander, Bill 5, 361 Baglow, Jessica 288 Bate, Jonathan 46n19, 129n38, 146n1, 154, Alexandra, Princess, the Hon. Lady Bagnall, Nick 296–7, 332 167n9, 238n50, 239n52 Ogilvy 56 Bahl, Ankur 293–4 Bateman, Tom 312, 338 Allam, Roger 290 Bailey, Thomas 334 Battista Guarini, Giovanni 184n8 Allen, Megan 228–39n53, 388 Baker, David J.