Shakespeare's Romance of Knowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tempest -THEATRICS

!1 THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare Edited by Tiffany Antone for The@trics Theatre Characters ALONSO, king of Naples SEBASTIAN, his brother PROSPERO, the right duke of Milan ANTONIO, his brother, the usurping duke of Milan FERDINAND, son to the king of Naples GONZALO, an honest old Counsellor CALIBAN, a savage and deformed Slave BIG TRINCULO & LITTLE TRINCULO, Jesters STEPHANO, a drunken Butler MIRANDA, daughter to Prospero ARIELS - five elemental spirits: FIRE, AIR, WATER, EARTH, and ETHER Master of a Ship, Boatswain, and Mariners ACT 1, SCENE 1 - On a ship at sea: a tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning heard. Enter a Master and a Boatswain MASTER Boatswain! BOATSWAIN Here, master: what cheer? MASTER Good, speak to the mariners: fall to't, yarely, or we run ourselves aground: bestir, bestir. Exit Enter Mariners BOATSWAIN Heigh, my hearts! cheerly, cheerly, my hearts! yare, yare! Take in the topsail. Tend to the master's whistle. Blow, till thou burst thy wind, if room enough! Enter ALONSO, SEBASTIAN, ANTONIO, FERDINAND, and GONZALO ALONSO Good boatswain, have care. Where's the master? !2 BOATSWAIN I pray now, keep below. ANTONIO Where is the master, boatswain? BOATSWAIN You mar our labour: keep your cabins: you do assist the storm. GONZALO Nay, good, be patient. BOATSWAIN. When the sea is. Hence! What cares these roarers for the name of king? To cabin: silence! trouble us not. GONZALO Good, yet remember whom thou hast aboard. BOATSWAIN. None that I more love than myself. You are a counsellor; if you can command these elements to silence, and work the peace of the present, we will not hand a rope more; use your authority: if you cannot, give thanks you have lived so long, and make yourself ready in your cabin for the mischance of the hour, if it so hap. -

Miranda: a Pinnacle of Femininity and Object of Patriarchal Power (A Study of Shakespeare‘S ―The Tempest‖) Mrs

Special Issue Published in International Journal of Trend in Research and Development (IJTRD), ISSN: 2394-9333, www.ijtrd.com Miranda: A Pinnacle of Femininity and Object of Patriarchal Power (A Study of Shakespeare‘s ―The Tempest‖) Mrs. Divya K.B, Associate Professor, Dept of English, Jindal First Grade College For WomenJindalnagar, Bangalore, India Abstract: Shakespeare was not of an age but for all times because his characters are true to the eternal aspects of human life and not limited to contemporary society. Shakespeare was also the soul of his age. By its very nature drama is a mirror of its times. He wrote for Elizabethan audience and he conditioned his art to suit the tastes of the people and the limitations of the age. Shakespeare‘s greatness, one critic said lay in his comprehensive soul. That is the most poetic summation of a dramatic genius that has never been equaled. No dramatist can create live characters save by bequeathing the best of himself into his work of art, scattering among them a largess of his own qualities, his own wit, his comprehensive cogent philosophy, his own rhythm of action and the simplicity or complexity of his own nature. Shakespeare excelled in all of them all the time, or at least majority of times, as he teased and tormented his readers with his exquisite wit on one scale and sublimated them with his deep insight into human psyche on another. Shakespeare wrote in the age outstanding in literary history and its vitality of language. During the time of Shakespeare, there was a social construct of daughter Miranda to her rightful place using illusion and skilful gender and sexuality norms just as there are today. -

Characters from the Tempest – from the Site “No Fear Shakespeare”

Characters from The Tempest – From the site “No Fear Shakespeare” Prospero The play’s protagonist and Miranda’s father. Twelve years before the events of the play, Prospero was the duke of Milan. His brother, Antonio, in concert with Alonso, king of Naples, usurped him, forcing him to flee in a boat with his daughter. The honest lord Gonzalo aided Prospero in his escape. Prospero has spent his twelve years on an island refining the magic that gives him the power he needs to punish and reconcile with his enemies. Miranda Prospero’s daughter, whom he brought with him to the island when she was still a small child. Miranda has never seen any men other than her father and Caliban, although she dimly remembers being cared for by female servants as an infant. Because she has been sealed off from the world for so long, Miranda’s perceptions of other people tend to be naïve and non- judgmental. She is compassionate, generous, and loyal to her father. Ariel Prospero’s spirit helper, a powerful supernatural being whom Prospero controls completely. Rescued by Prospero from a long imprisonment (within a tree) at the hands of the witch Sycorax, Ariel is Prospero’s servant until Prospero decides to release him. He is mischievous and ubiquitous, able to traverse the length of the island in an instant and change shapes at will. Ariel carries out virtually every task Prospero needs accomplished in the play. Caliban Another of Prospero’s servants. Caliban, the son of the now-deceased witch Sycorax, acquainted Prospero with the island when Prospero arrived. -

SHAKESPEARE and RODO'': RECURRING THEMES and CHARACTERS by WENDELL AYCOCK, B.A» a THESIS in ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate F

SHAKESPEARE AND RODO'': RECURRING THEMES AND CHARACTERS by WENDELL AYCOCK, B.A» A THESIS IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Technological College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Accepted 79^5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Professor Joseph T. McCullen for his direction of this thesis• ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. ARIEL AND THE TEMPEST: A SURVEY ^ Rode'''s Life and Reputation 5 Ariel 8 The Tempest 29 III. ARIEL AND THE TEMPEST: A COMPARISON .... 3^ Introduction • . • 5^ The Societies of Shakespeare and Rodo*^ ... 35 The Conflict of Spiritual and Material Interests ^ Ariel, Caliban, and Prosper© 42 IV. CONCLUSION 54 BIBLIOGRAPHY 56 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION One of the important aspects of a study of literature is relativity. In trying to understand the universality of literature, scholars aj?e continually discovering and relating recurring themes, literary techniques, and characters. By studying recurring themes, scholars can understand the ideas and problems which have interested authors of many eras. By studying recurring literary techniques, they can see the value of techniques which have been useful throughout history. And, by studying reciorring characters (or types of characters), they can L-"' / understand the qualities of human nature which are un- ^^ changing. Possibly the most interesting consideration of this type of relativity is the comparison of recurring char acters. Authors sometimes choose, as subjects for their own literary works, characters that have been created by another author. When such a choice is made, and when the recreated characters are not renamed, the student of literature becomes especially interested in trying to compare the two works and the characters that are used in both works. -

Teacher Resource Pack I, Malvolio

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK I, MALVOLIO WRITTEN & PERFORMED BY TIM CROUCH RESOURCES WRITTEN BY TIM CROUCH unicorntheatre.com timcrouchtheatre.co.uk I, MALVOLIO TEACHER RESOURCES INTRODUCTION Introduction by Tim Crouch I played the part of Malvolio in a production of Twelfth Night many years ago. Even though the audience laughed, for me, it didn’t feel like a comedy. He is a desperately unhappy man – a fortune spent on therapy would only scratch the surface of his troubles. He can’t smile, he can’t express his feelings; he is angry and repressed and deluded and intolerant, driven by hate and a warped sense of self-importance. His psychiatric problems seem curiously modern. Freud would have had a field day with him. So this troubled man is placed in a comedy of love and mistaken identity. Of course, his role in Twelfth Night would have meant something very different to an Elizabethan audience, but this is now – and his meaning has become complicated by our modern understanding of mental illness and madness. On stage in Twelfth Night, I found the audience’s laughter difficult to take. Malvolio suffers the thing we most dread – to be ridiculed when he is at his most vulnerable. He has no resolution, no happy ending, no sense of justice. His last words are about revenge and then he is gone. This, then, felt like the perfect place to start with his story. My play begins where Shakespeare’s play ends. We see Malvolio how he is at the end of Twelfth Night and, in the course of I, Malvolio, he repairs himself to the state we might have seen him in at the beginning. -

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma As Drama in the Tempest Jeffrey R

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma as Drama in The Tempest Jeffrey R. Wilson The dramatis personae of The Tempest casts Caliban as “asavageand deformed slave.”1 Since the mid-twentieth century, critics have scrutinized Caliban’s status as a “slave,” developing a riveting post-colonial reading of the play, but I want to address the pairing of “savage and deformed.”2 If not Shakespeare’s own mixture of moral and corporeal abominations, “savage and deformed” is the first editorial comment on Caliban, the “and” here Stigmatized as such, Caliban’s body never comes to us .”ס“ working as an uninterpreted. It is always already laden with meaning. But what, if we try to strip away meaning from fact, does Caliban actually look like? The ambiguous and therefore amorphous nature of Caliban’s deformity has been a perennial problem in both dramaturgical and critical studies of The Tempest at least since George Steevens’s edition of the play (1793), acutely since Alden and Virginia Vaughan’s Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural His- tory (1993), and enduringly in recent readings by Paul Franssen, Julia Lup- ton, and Mark Burnett.3 Of all the “deformed” images that actors, artists, and critics have assigned to Caliban, four stand out as the most popular: the devil, the monster, the humanoid, and the racial other. First, thanks to Prospero’s yarn of a “demi-devil” (5.1.272) or a “born devil” (4.1.188) that was “got by the devil himself” (1.2.319), early critics like John Dryden and Joseph War- ton envisioned a demonic Caliban.4 In a second set of images, the reverbera- tions of “monster” in The Tempest have led writers and artists to envision Caliban as one of three prodigies: an earth creature, a fish-like thing, or an animal-headed man. -

Caliban's Use of Language in Shakespeare's the Tempest

fi4 Notions Vol.6 No3 2015 (P) ISSN t 097G5247, (epSSN: 239*7239 Caliban's Use of Language in Shakespearers The Tbmpest You taught me language, and my profit on,t Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you For learning me your language! (Act I, Scene II, The Tempest) ..The Richard Eyre, a distinguished English director said, life of the plays is in the language, not alongside ig or underneath i1. f'sslings and thoughts are released at the moment of speech. An Elizabethan audience would have responded to the pulse, the rhythms, the shapes, sounds, and above all meanings, within the consistent ten- syllable, five- stress lines of blank verse. They were an audience who listened,,. (Shakespeareb Language 4) At the outset, the audience has to make a distinction between some modern connotations ofthe word 'language, and those current in Shakespeare's day, when language was neither neutal nor purely verbal. A neutral view of language is typified by such statements as Saussure,s remark: From the excursions made into regions bordering upon linguistics, there emerges a negative lesson, but one which...supports the fundamental thesis of this course: the only true object of study in linguistics is the language, considered in itself and for its own sake. (Course inGeneral Linguistics) Such an empirical approachwas alientothe sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, where all concems of life were moralizod, including language, in so far as most writers looked for ways of integrating their subject with the current dominant Christian concepts. Language and knowledge has been the key to power on the island in the play. -

The Tempest: Synopsis by Jo Miller, Grand Valley Shakespeare Festival Dramaturg

The Tempest: Synopsis By Jo Miller, Grand Valley Shakespeare Festival Dramaturg Long ago and far away, Prospero, the Duke of Milan, pursued the contemplative life of study while turning the administration of his Dukedom over to his brother [in our play a sister, Antonia], who, greedy for power, made a deal with the King of Naples to pay tribute to the King in exchange for help in usurping Prospero’s title. Together they banished Prospero from Milan, thrusting him out to sea in a rotten, leaky boat with his infant daughter, Miranda. Miraculously, the father and daughter survived and were marooned on an island where Sycorax, an evil witch who died after giving birth to Caliban, had also been exiled. Caliban is thus the only native inhabitant of the isle besides the spirit, Ariel, and his fellow airy beings. For twelve years now, Prospero and Miranda have lived in exile on this island, with Prospero as its de facto king, ruling over Caliban and all the spirits as his slaves, while he has nurtured Miranda and cultivated his powerful magic. At the moment play begins, that same King of Naples and his son Prince Ferdinand, along with the King’s brother [here a sister, Sebastiana], Prospero’s sister, Antonia, and the whole royal court, are sailing home from having given the Princess Claribel in marriage to the King of Tunis. Prospero conjures up a mighty tempest, which wrecks the King’s boat on the island, separating the mariners from the royal party, and isolating Ferdinand so that the King believes him drowned. -

What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo

Kunapipi Volume 16 Issue 3 Article 13 1994 What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo Chantal Zabus Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Zabus, Chantal, What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo, Kunapipi, 16(3), 1994. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol16/iss3/13 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo Abstract Each century seems to have its own interpellative dream-text: The Tempest for the 17th century; Robinson Crusoe for the 18th century; Jane Eyre for the 19th century; Heart of Darkness for the turn of this century. Such texts serve as pre-texts to others; they underwrite them. Yet, in its nearly four centuries of existence, The Tempest has washed ashore more alluvial debris than any other text: parodies, rewritings and adaptations of all kinds. Incessantly, we keep revisiting the stage of Shakespeare's island and we continue to dredge up new meanings from its sea-bed. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol16/iss3/13 What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo 81 CHANTAL ZABUS What Next Miranda?: Marina Warner's Indigo 1 'What next I wonder?' Iris Murdoch, The Sea, the Sea Each century seems to have its own interpellative dream-text: The Tempest for the 17th century; Robinson Crusoe for the 18th century; Jane Eyre for the 19th century; Heart of Darkness for the turn of this century. -

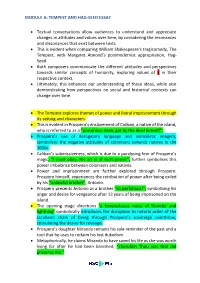

Module A: Tempest and Hag-Seed Essay

MODULE A: TEMPEST AND HAG-SEED ESSAY • Textual conversations allow audiences to understand and appreciate changes in attitudes and values over time, by considering the resonances and dissonances that exist between texts. • This is evident when comparing William Shakespeare’s tragicomedy, The Tempest, with Margaret Atwood’s postmodernist appropriation, Hag- Seed. • Both composers communicate the different attitudes and perspectives towards similar concepts of humanity, exploring values of x in their respective context. • Ultimately, this enhances our understanding of these ideas, while also demonstrating how perspectives on social and historical contexts can change over time. • The Tempest explores themes of power and literal imprisonment through its setting and characters. • This is evident in Prospero’s enslavement of Caliban, a native of the island, who is referred to as a “poisonous slave, got by the devil himself”. • Prospero’s use of derogatory language and animalistic imagery, symbolises the negative attitudes of colonisers towards natives in the 1600s. • Caliban’s submissiveness, which is due to a paralysing fear of Prospero’s magic, “I must obey. His art is of such power”, further symbolises this power imbalance between colonisers and natives. • Power and imprisonment are further explored through Prospero. Prospero himself, experiences the retribution of power after being exiled by his “unlawful brother”, Antonio. • Prospero presents Antonio as a brother “so perfidious!”, symbolising his anger and desire for vengeance after 12 years of being imprisoned on the island. • The opening stage directions ‘a tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning’ symbolically introduces the disruption to natural order of the Jacobean chain of being through Prospero’s sovereign overthrow, stimulating the desire for revenge. -

The Tempest Summary: a Magical Storm

The Tempest Summary: A Magical Storm The Tempest begins on a boat, tossed about in a storm. Aboard is Alonso the King of Naples, Ferdinand (his son), Sebastian (his brother), Antonio the usurping Duke of Milan, Gonzalo, Adrian, Francisco, Trinculo and Stefano. Miranda, who has been watching the ship at sea, is distraught at the thought of lost lives. The storm was created by her father, the magical Prospero, who reassures Miranda that all will be well. Prospero explains how they came to live on this island: they were once part of Milan’s nobility – he was a Duke and Miranda the baby princess. However, Prospero’s brother (Antonio) exiled them – they were placed on a boat and banished, never to be seen again. Prospero summons Ariel, his servant spirit. Ariel explains that he has carried out Prospero’s orders: he destroyed the ship and dispersed its passengers across the island. Prospero instructs Ariel to be invisible and spy on them. Ariel asks when he will be freed and Prospero chastises him for being ungrateful, promising to free him soon, when his work is done. Caliban: Man or Monster? Prospero decides to visit his other servant, Caliban, but Miranda is reluctant, describing him as a monster. Prospero agrees that Caliban can be rude and unpleasant, but is invaluable for the menial tasks he performs for them. When Prospero and Miranda meet Caliban, we learn that he is native to the island, but Prospero turned him into a slave raising issues about morality and fairness in the play. Love at First Sight Ferdinand stumbles across Miranda and they fall in love and decide to marry. -

And Margaret Atwood's Novel Hag-Seed

The textual conversation between William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest (1611) and Margaret Atwood’s novel Hag-Seed (2016) positions readers to realise how individuals must move on from the past in order to achieve fulfilment. Readers recognise how introspection and accepting the past is necessary in order to reconcile with loss and how to achieve freedom, individuals must overcome their restrictive, seemingly predestined capacities. Atwood’s appropriation of The Tempest allows contemporary audiences to gain true insight into the timeless values of self-reflection, reconciliation and challenging one’s destiny. The textual conversation between The Tempest and Hag-Seed facilitates readers’ appreciation of how introspection and accepting the past is necessary in order to reconcile with loss. In The Tempest, Shakespeare advocates how Prospero’s introspection as he moves on from his preoccupation with revenge, prompts compassion and forgiveness. Shakespeare responds to the rise of Renaissance Humanism during the Jacobean Era, celebrating human control over one’s fate and display of virtues such as empathy and self-enquiry. Shakespeare characterises exiled Duke of Milan Prospero as unwilling to acknowledge how his usurpation by his brother Antonio resulted from preoccupations with magic as he accuses Antonio of being the metaphorical "ivy which had hid my princely trunk” to emphasise his loss and victimise himself. Shakespeare establishes Prospero’s anger towards his past betrayal in the supernatural stage directions [Enter several strange shapes, bringing in a banquet…] and [...the banquet vanishes], revealing how he uses magic to humiliate and punish the shipwrecked Royal Court. However, Shakespeare exposes how Prospero’s belief that revenge is justified is challenged by spirit Ariel in “if you now beheld them, your affections would become tender….