Kim Tallbear: "Disrupting Settlement, Sex, and Nature"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum

Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 1 May 2016 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 2 May 2017 V o l u m e 2 M a y 2 0 1 7 Editorial 4-7 Anita Thaler & Birgit Hofstätter Making kin, or: The art of kindness and why there is nothing romantic about it 8-14 Birgit Hofstätter Non-monogamies and queer kinship: personal-political reflections 15-27 Boka En, Michael En, David Griffiths & Mercedes Pölland Thirteen Grandmothers, Queering Kinship and a "Compromised" Source 28-38 Daniela Jauk The Queer Custom of Non-Human Personhood Kirk J Fiereck 39-43 Connecting different life-worlds: Transformation through kinship (Our experience with poverty alleviation ) 44-58 Zoltán Bajmócy in conversation with Boglárka Méreiné Berki, Judit Gébert, György Málovics & Barbara Mihók Queer STS – What we tweeted about … 59-64 2 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 2 May 2017 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum A Journal of the Working Group Queer STS Editors Queer STS Anita Thaler Anita Thaler Birgit Hofstätter Birgit Hofstätter Daniela Zanini-Freitag Reviewer Jenny Schlager Anita Thaler Julian Anslinger Birgit Hofstätter Lisa Scheer Julian Anslinger Magdalena Wicher Magdalena Wicher Susanne Kink Thomas Berger Layout & Design [email protected] Julian Anslinger www.QueerSTS.com ISSN 2517-9225 3 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 1 May 2016 Anita Thaler & Birgit Hofstätter Editorial This second Queer-Feminist Science and Technology Studies Forum is based on inputs, thoughts and discussions rooted in a workshop about "Make Kin Not Babies": Discuss- ing queer-feminist, non-natalist perspectives and pro-kin utopias, and their STS implica- tions” during the STS Conference 2016 in Graz. -

Place Me in Gettysburg: Relating Sexuality to Environment

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2021 Place Me in Gettysburg: Relating Sexuality to Environment Kylie R. Mandeville Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Mandeville, Kylie R., "Place Me in Gettysburg: Relating Sexuality to Environment" (2021). Student Publications. 937. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/937 This open access digital project is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Place Me in Gettysburg: Relating Sexuality to Environment Abstract This project links sexuality and environmental issues in the context of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. It considers how I, a queer student at Gettysburg College, can be in “right relations” with this environment. While queer ecological scholarship defines “right elations”r as relationships where all beings—people of all identities, as well as animals, plants, and the land—can flourish through their interactions, I inquire whether such flourishing is possible for me, and others like me, here in this place. To answer this question, the project links queer ecological scholarship with environmental history scholarship specific ot the Gettysburg battlefield and civil war. It also involves research into archival and contemporary articles about the battlefield and the college. I created a website using Scalar to present this research interwoven with my personal experiences as prose essays, accompanied by artwork. I found that queer students at Gettysburg don’t fit into the heteronormative fraternity-based social environment and can feel “unnatural” and alienated from the campus community. -

Queer, Indigenous, and Multispecies Belonging Beyond Settler Sex & Nature July 25, 2019

IMAGINATIONS: JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES | REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE Publication details, including open access policy and instructions for contributors: http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca Critical Relationality: Queer, Indigenous, and Multispecies Belonging Beyond Settler Sex & Nature July 25, 2019 To cite this article: TallBear, Kim, and Angela Willey. “Introduction: Critical Relationality: Queer, Indigenous, and Multispecies Belonging Beyond Settler Sex & Nature.” Imaginations, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 5–15. DOI dx.doi.org/10.17742/ IMAGE.CR.10.1.1 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.CR.10.1.1 The copyright for each article belongs to the author and has been published in this journal under a Creative Commons 4.0 International Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives license that allows others to share for non-commercial purposes the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal. The content of this article represents the author’s original work and any third-party content, either image or text, has been included under the Fair Dealing exception in the Canadian Copyright Act, or the author has provided the required publication permissions. Certain works referenced herein may be separately licensed, or the author has exercised their right to fair dealing under the Canadian Copyright Act. CRITICAL RELATIONALITY: QUEER, INDIGENOUS, AND MULTISPECIES BELONGING BEYOND SETTLER SEX & NATURE KIM TALLBEAR AND ANGELA WILLEY his special issue of -

The Indigenous Sovereign Body: Gender, Sexuality and Performance

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Art & Art History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 12-15-2017 The ndiI genous Sovereign Body: Gender, Sexuality and Performance. Michelle S. McGeough University of New Mexico Michelle Susan McGeough University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation McGeough, Michelle S. and Michelle Susan McGeough. "The ndI igenous Sovereign Body: Gender, Sexuality and Performance.." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds/67 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art & Art History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Michelle S. A. McGeough Candidate Art Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joyce Szabo, Chairperson Dr. Kency Cornejo Dr. Carla Taunton Aaron Fry, ABD THE INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGN BODY: GENDER, SEXUALITY AND PERFORMANCE By Michelle S.A. McGeough B.Ed., University of Alberta, 1982 A.A., Institute of American Indian Art, 1996 B.F.A., Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design University, 1998 M.A., Carleton University, 2006 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2017 Dedication I wish to dedicate these thoughts and words to the two women whose names I carry, my Grandmothers− Susanne Nugent McGeough and Mary Alice Berard Latham. -

Remapping the World: Vine Deloria, Jr. and the Ends of Settler Sovereignty

Remapping the World: Vine Deloria, Jr. and the Ends of Settler Sovereignty A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY David Myer Temin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joan Tronto October 2016 © David Temin 2016 i Acknowledgements Perhaps the strangest part of acknowledging others for their part in your dissertation is the knowledge that no thanks could possibly be enough. At Minnesota, I count myself lucky to have worked with professors and fellow graduate students alike who encouraged me to explore ideas, take intellectual risks, and keep an eye on the political stakes of any project I might pursue. That is why I could do a project like this one and still feel emboldened that I had something important and worthwhile to say. To begin, my advisor, Joan Tronto, deserves special thanks. Joan was supportive and generous at every turn, always assuring me that the project was coming together even when I barely could see ahead through the thicket to a clearing. Joan went above and beyond in reading countless drafts, always cheerfully commenting or commiserating and getting me to focus on power and responsibility in whatever debate I had found myself wading into. Joan is a model of intellectual charity and rigor, and I will be attempting to emulate her uncanny ability to cut through the morass of complicated debates for the rest of my academic life. Other committee members also provided crucial support: Nancy Luxon, too, read an endless supply of drafts and memos. She has taught me more about writing and crafting arguments than anyone in my academic career, which has benefited the shape of the dissertation in so many ways. -

Representations of Texas Indians in Texas Myth and Memory: 1869-1936

REPRESENTATIONS OF TEXAS INDIANS IN TEXAS MYTH AND MEMORY: 1869-1936 A Dissertation by TYLER L. THOMPSON Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Angela Hudson Committee Members, Walter Buenger Carlos Blanton Cynthia Bouton Joseph Jewell Head of Department, David Vaught August 2019 Major Subject: History Copyright 2019 Tyler Leroy Thompson ABSTRACT My dissertation illuminates three important issues central to the field of Texas Indian history. First, it examines how Anglo Texans used the memories of a Texas frontier with “savage” Indians to reinforce a collective identity. Second, it highlights several instances that reflected attempts by Anglo Texans to solidify their place as rightful owners of the physical land as well as the history of the region. Third, this dissertation traces the change over time regarding these myths and memories in Texas. This is an important area of research for several reasons. Texas Indian historiography often ends in the 1870s, neglecting how Texas Indians abounded in popular literature, memorials, and historical representations in the years after their physical removal. I explain how Anglo Texans used the rhetoric of race and gender to “other” indigenous people, while also claiming them as central to Texas history and memory. Throughout this dissertation, I utilize primary sources such as state almanacs, monument dedication speeches, newspaper accounts, performative acts, interviews, and congressional hearings. By investigating these primary sources, my goal is to examine how Anglo Texans used these representations in the process of dispossession, collective remembrance, and justification of conquest, 1869-1936. -

Native American Dna

Klr"1 TALLBEAR IihTIVE ~~ERIChli DIi~ Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science NATIVE AMERICAN DNA Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science Kim TallBear UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS MINNEAPOLIS I LONDON A different version of chapter 2 was puhlished as "Native-American- DNA.com: In Search of Native American Race and Tribe," in Revisitill,g Race ill ({ Genomic Age, ed. Barbara Koenig, Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, and Sarah S. Richardson (Piscataway, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2(08), 235-52. Portions of chapter 4 were previously published as "Narratives of Race and Indigeneity in the Genographic Project," Jounla/ ofl.au: Medicine. and l/rhic: 35, no. 3 (Fall 2(07): 412-24. Dedicated to my late grandmother, Copyright 2013 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Arlene Heminger-Lamb, a Dakota woman, who symbolizes for me all those who think deeply on things, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a but whose choices are few. retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, ,\-iN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data lallBear, Kimberly. Native American DNA: tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science / Kim ~IallBear. Includes bihliograpbical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-6585-3 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8166-6586-0 (ph : alk. -

Title: “NATIVE AMERICAN DNA - Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science”

Page 1 of 48 Title: “NATIVE AMERICAN DNA - Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science” < Author: Kim TallBear ::::::::::: ABOUT: http://kimtallbear.com/ :: http://kimtallbear.com/contact/ :: [ORIGINAL] CONTENTS listing :: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX INTRODUCTION :An Indigenous, Feminist Approach to DNA Politics 1 1. Racial Science, Blood, and DNA 31 2. The DNA Dot-com: Selling Ancestry 67 3. Genetic Genealogy Online 105 4. The Genographic Project: The Business of Research and Representation 143 CONCLUSION Indigenous and Genetic Governance and Knowledge 177 NOTES 205 :: INDEX 237 [ SUSAN’s WORD VERSION ] EXPANDED CONTENTS :: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX :: INTRODUCTION :AN INDIGENOUS, FEMINIST APPROACH TO DNA POLITICS 2 - WHAT Is NATIVE AMERICAN DNA? 3 - A Culmination of HistOrY find Narrative 11 - Who Studies? Who Gets Studied? 14 - Standpoint ?? - How I PRODUCE My KNOWLEDGE: THEORY, METHOD, AND ETHICS 18 - Analytical Frameworks: Coproduction (of Natural and Social Order) and Articulation 20 - The Sins and Stories of Anthropology: Embraces and Refusals 24 - "Decolonizing" Research 32 - Feminist and Indigenous Epistemologies at One Table 38 - "Objectivity" and Situated Knowledges 38 - RESEARCHING, CONSUMING, AND CAPITALIZING ON NATIVE AMERICAN DNA 42 CHAPTERs: 1. Racial Science, Blood, and DNA (coming) 2. The DNA Dot-com: Selling Ancestry (coming) 3. Genetic Genealogy Online (coming) 4. The Genographic Project: The Business of Research and Representation (coming) CONCLUSION: Indigenous and Genetic Governance and Knowledge (coming) NOTES 205 INDEX 237 Page 2 of 48 [hyperlikes and ‘notes’ added by Susan] INTRODUCTION AN INDIGENOUS, FEMINIST APPROACH TO DNA POLITICS Scientists and the Public alike are on the hunt for "Native American DNA." Hi-tech genomics labs [A] at universities around the world search for answers to questions about human origins and ancient global migrations. -

Tallbear, Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family

Making Kin Not Population Edited by Adele E. Clarke and Donna Haraway PRICKLY PARADIGM PRESS CHICAGO Contents Introducing Making Kin Not Pqpulation ...................... 1 Adele E. Clarke 1. Black AfterLivcs Matter: Cultivating IGnfulness as Reproductive Justice ......... .41 Ruha Benjamin 2. Making IGn in the Chthulucene: Reproducing Multispecies Justice .......................... ,..... 67 Donna Haraway 3. Against Population, Towards Afterlife ................. .101 Miehe.Ile Murphy 4. New Feminist Biopolitics for © 2018 by the authors. Ultra-low-fertility East Asia .. ............. : .................... ;.125 All rights reserved. Yu-Ling Huang and Chia-Ling Wu Prickly Paradigm Press, LLC 5. Making Love and Relations 5629 South University Avenue Beyond Settler Sex and Family ......... , ........................ 145 Chicago, IL 60637 Kim TallBear www.prickly-paradigm.com References ......................................... , ........................... 167 ISBN: 9780996635561 LCCN: 2018941392 Printed in the United States ofAmerica on acid-free paper. 144 \Vu's work offers "a nc,v \Vay of telling our new real ity," :is feminist science fictionist Ursub Le Guin prJised. Such work urges us to investigate new concepts, mindsets, and actions to revamp relations between population, eGmomy, :md enviromm:nt while making; new forms of kin. Ultra-low fertility can be regarded as a nJtional security crisis, bl1t it cJn also be a strong stirnubnt for :i. more en-connected nnv world. 5 Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family Kim Tal!Bear Sufficiency At n ifiFc-fl.JPll1'-JJ>C do them often a-t po1p-wowr-t/Jc Jami~!' brmo1·s one of our own by thm1/ci11Jr the Pcopk 1Pho ji113lc and s/Ji1m11cr in circle. ]7;cy 1?/'c with 11s. Wcl7iPcpifi:s in fmth,tTcncnms sho1;, nllff. -

Making Kin in the Chthulucene Donna J

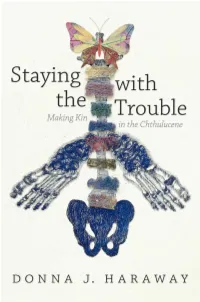

Staying with the Trouble Experimental Futures: Technological lives, scientific arts, anthropological voices A series edited by Michael M. J. Fischer and Joseph Dumit Staying with the Trouble Making Kin in the Chthulucene Donna J. Haraway duke university press durham and london 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press Chapter 1 appeared as “Jeux de ficelles avecs All rights reserved des espèces compagnes: Rester avec le trou- Printed in the United States of America ble,” in Les animaux: deux ou trois choses que on acid-free paper ∞ nous savons d’eux, ed. Vinciane Despret and Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Raphaël Larrère (Paris: Hermann, 2014), Typeset in Chaparral Pro by Copperline 23–59. © Éditions Hermann. Translated by Vinciane Despret. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Chapter 4 is lightly revised from “Anthropo- Publication Data. Names: Haraway, cene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthu- Donna Jeanne, author. Title: Staying lucene: Making Kin,” which was originally with the trouble : making kin in the published in Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, Chthulucene / Donna J. Haraway. under Creative Commons license cc by-nc-nd Description: Durham : Duke University 3.0. © Donna Haraway. Press, 2016. | Series: Experimental futures: technological lives, scientific Chapter 5 is reprinted from wsq: Women’s arts, anthropological voices | Includes Studies Quarterly 40, nos. 3/4 (spring/sum- bibliographical references and index. | mer 2012): 301–16. Copyright © 2012 by the Description based on print version re- Feminist Press at the City University of New cord and cip data provided by publisher; York. Used by permission of The Permissions resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn Company, Inc., on behalf of the publishers, 2016019477 (print) | lccn 2016018395 feministpress.org. -

Tallbear – Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family

Borrower: WAU Call#: GFSO .M35 2018 Lending String: Location: STACKS ORE,HTM ,TXX,OKU ,LRU ,FDA,BTS,AAA,*DKC ,G ZM ,OBE,PSC,TKN ,EMU Mail Patron: Charge Maxcost: 80 .00IFM Journal Title: Making kin not population I Shipping Address: Volume: Issue: ILL - Libraries Month/Year: 2018Pages: 145-209 University of Washington 4000 15th Ave NE Box 352900 Seattle, Washington 98195-2900 Article Author: Kim TallBear United States Article Title: Making Love and Re lations Beyond Fax: Settler Sex and Family Ariel: Imprint: Chicago, IL : Prickly Paradigm Press, [2018] ©2018 "C C'O ILL Number: 193301001 ...J ...J Illllll lllll lllll lllll 111111111111111111111111111111111 144 Wu's work offers "a new way of telling our new real ity,'' as feminist science fictionist Ursula Le Guin praised. Such work urges us to investigate new concepts, mindsets, and actions to revamp relations between population, economy, and environment while making new forms of kin. Ultra-low fertility can be regarded as a national security crisis, but it can also be a strong stimulant for a more en-connected new world. 5 Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family Kim TallBear Sufficiency At a give-away-we do them often at pow-wows-the family honors one of our own by thanking the People who jingle and shimmer in circle. They arc with us. We give gifts in both generous show and as acts offaith in sufficiency. One docs not future-hoard. We may lament incomplete colonial conversions, our too little bank savings. The circle, we hope, will sustain. We sustain it. Not so strange then that I decline to hoard love and another's body for myself? I cannot have faith in scarcity. -

The Colonial Project of Gender (And Everything Else)

genealogy Article The Colonial Project of Gender (and Everything Else) Sandy O’Sullivan Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: The gender binary, like many colonial acts, remains trapped within socio-religious ideals of colonisation that then frame ongoing relationships and restrict the existence of Indigenous peoples. In this article, the colonial project of denying difference in gender and gender diversity within Indigenous peoples is explored as a complex erasure casting aside every aspect of identity and replacing it with a simulacrum of the coloniser. In examining these erasures, this article explores how diverse Indigenous gender presentations remain incomprehensible to the colonial mind, and how reinstatements of kinship and truth in representation fundamentally supports First Nations’ agency by challenging colonial reductions. This article focuses on why these colonial practices were deemed necessary at the time of invasion, and how they continue to be forcefully applied in managing Indigenous peoples into a colonial structure of family, gender, and everything else. Keywords: queer First Nations; queer Indigenous; non-binary Indigenous; First Nations museums; First Nations gender; colonial gender 1. The Colonial Project of Gender (and Everything Else) A central tenet of the project of colonisation is a reductive examination of the lives of Indigenous peoples, casting them as dysfunctional, inferior versions of colonial home state actors (Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson 2016, p. 789). The project of embedding these ideas in colonial lands also relies on the colonial state actors’ disconnection from their own Citation: O’Sullivan, Sandy. 2021. deep histories, wherein they replace their beliefs and nuances with faith in the colonial The Colonial Project of Gender (and state and enact this belief on others.