The Indigenous Sovereign Body: Gender, Sexuality and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asia Fiber Public Company Limited

ASIA FIBER PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED PRODUCTS (All our products) NYLON FOY (1.5 Kgs. BB) NYLON POY (11 Kgs. BB) NYLON FDY ( 9 Kgs. BB) / / / YARN COUNT LUSTER YARN COUNT LUSTER High Tenacity 70D/24F SEMI DULL 50D/12F SEMI DULL YARN COUNT LUSTER 100D/24F SEMI DULL 88D/24F SEMI DULL 210D/24F* BRIGHT 200D/48F SEMI DULL 118D/24F SEMI DULL 420D/48F BRIGHT 125D/34F SEMI DULL 630D/72F BRIGHT 840D/96F BRIGHT NYLON TEXTURED YARN 1050D/120F BRIGHT YARN COUNT PLY TYPE LUSTER FINISHED 1260D/144F BRIGHT 40D/12F 1 SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED 1680D/192F BRIGHT 40D/12F 2 TWISTED SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED *4 Kgs. BB / 70D/24F 1 SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED 70D/24F 2 PARALLEL SEMI DULL R.W. FUNCTIONAL PRODUCTS 70D/24F 2 INTERMINGLED SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED POY, FDY DTY 70D/24F 2,3,4 TWISTED SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED - ANTI BACTERIA - MOISTURE MANAGEMENT 100D/24F 1 SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED - DOPE - DYED YARN - ANTI BACTERIA 100D/24F 2 PARALLEL SEMI DULL R.W. - DOPE - DYED YARN 100D/24F 2 INTERMINGLED SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED - RECYCLED DYED YARN 100D/24F 2,3,4,6 TWISTED SEMI DULL R.W. or DYED NYLON POLYESTER WOVEN FABRIC / KIND OF FABRIC WARPxWEFT LUSTER WIDTH 190T NYLON TAFFETA 70D x 70D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" 210T NYLON TAFFETA 70D x 70D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" 210T NYLON RIPSTOP 70D x 70D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" NYLON SATIN 70D x 100D BRIGHT x SEMI DULL 60" NYLON OXFORD 210D x 210D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" NYLON OXFORD 420D x 420D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" NYLON TASLAN 70D x 160D(ATY) SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" 190T POLYESTER TAFFETA 75D x 75D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" POLYESTER TEXTURE 75D x 75D SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" POLYESTER TASLAN 75D x 175D(ATY) SEMI DULL x SEMI DULL 60" POLYESTER NYLON TAFFETA FABRIC WITH WATER / NYLON POLYESTER TWILL 70D x 75D TRILOBAL x BRIGHT 60" RESISTANCE FINISHING TESTED BY THTI FINISHING : PLAIN DYED, RESIN FINISHED, WATER PROOF, WATER REPELLENT, CIRE(CHINTZ), ( AATCC 127 AATCC 42 STANDARD ) WRINKLE(WASHER), PIGMENT / POLYURETHANE / ACRYLIC & INORGANIC COATINGS, / FOR CLASSIFICATION OF SURGICAL GOWN BARRIER ANTI BACTERIA, ANTI MOSQUITO, MOISTURE MANAGEMENT, ETC. -

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) Introduction Annie Oakley (1860-1926) was an American sharpshooter and exhibition shooter born in Darke County, Ohio, as Phoebe Ann Mosey. When she was five, her father died, and Annie learned to trap, shoot and hunt by age eight to help support her family. In 1875 (though some sources say it was in 1881), Annie met her future husband, Frank E. Butler, at the Baughman & Butler shooting act in Cincinnati, while beating him in a shooting contest. They were married a year later, and in 1885, they joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West where she was given the nickname “Little Sure Shot.” Considered America’s first female star, Oakley traveled all over the United States and Europe showing off her skills. Oakley set shooting records into her sixties, and also did philanthropic work for women’s rights and other causes. In 1925, she died in Greenville, Ohio. Important Dates . August 13, 1860: Annie Oakley is born Phoebe Ann Mosey in Darke County, Ohio. November 1875: Oakley defeats Frank E. Butler in a shooting contest. The pair marries a year later. 1885: Oakley and Butler join Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. 1889: Oakley travels to France to perform in the Paris Exposition. 1901: Oakley is injured in a train accident but recovers and returns to show business. 1912-1917: Oakley and Butler retire temporarily and reside in Cambridge, Maryland. 1917: Oakley and Butler move to North Carolina and return to public life. 1922: Oakley and Butler are injured in a car accident, but Oakley performs again a year or so later. -

Liberty Price List

LIBERTY PRICE LIST Lee County PRICE LIST - March 23, 2018 (Replaces all previous price lists) STYLE # ITEM FABRIC COLOR Origin Cost A 25% OFF 140MBK Police Sweater 100% acrylic Black I $ 62.60 $ 46.95 140MBN Police Sweater 100% acrylic Brown I $ 62.60 $ 46.95 140MNV Police Sweater 100% acrylic Navy I $ 62.60 $ 46.95 180MBK Flaps, Shirt Pocket / pair 100% acrylic Black M $ 6.40 $ 4.80 180MNV Flaps, Shirt Pocket / pair 100% acrylic Navy M $ 6.40 $ 4.80 181MBK Epaulets, Shirt / pair 100% acrylic Black M $ 6.40 $ 4.80 181MNV Epaulets, Shirt / pair 100% acrylic Navy M $ 6.40 $ 4.80 182MBK Zipper for shirts Black I $ 2.90 $ 2.18 182MTN Zipper for shirts Tan I $ 2.90 $ 2.18 182MWH Zipper for shirts White I $ 2.90 $ 2.18 420XBK BB cap, summer 100% cotton Black I $ 7.70 $ 5.78 420XNV BB cap, summer 100% cotton Dark Navy I $ 7.70 $ 5.78 421XNV BB cap, winter 100% cotton Black I $ 7.70 $ 5.78 421XNV BB cap, winter 100% cotton Dark Navy I $ 7.70 $ 5.78 505MBK Security Bomber Polyester oxford Black I $ 55.90 $ 41.93 505MBN Security Bomber Polyester oxford Brown I $ 55.90 $ 41.93 505MNV Security Bomber Polyester oxford Navy I $ 55.90 $ 41.93 506MBK Security Bomber w/epaulets Polyester oxford Black I $ 65.90 $ 49.43 506MBN Security Bomber w/epaulets Polyester oxford Brown I $ 65.90 $ 49.43 506MNV Security Bomber w/epaulets Polyester oxford Navy I $ 65.90 $ 49.43 507MBK Police Bomber Polyester oxford Black I $ 69.00 $ 51.75 507MNV Police Bomber Polyester oxford Navy I $ 69.00 $ 51.75 524MBK Reversible Police Windbreaker Polyester oxford Black / yellow -

Analysing Prostitution Through Dissident Sexualities in Brazil

Contexto Internacional vol. 40(3) Sep/Dec 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2018400300006 Queering the Debate: Analysing Prostitution Through Dissident Pereira & Freitas Sexualities in Brazil Amanda Álvares Ferreira* Abstract: The aim of this article is to contrast prominent discourses on prostitution and human trafficking to the context of prostitution in Brazil and local feminist discourses on this matter, un- derstanding their contradictions and limitations. I look at Brazilian transgender prostitutes’ experi- ences to address an agency-related question that underlies feminist theorizations of prostitution: can prostitution be freely chosen? Is it necessarily exploitative? My argument is that discourses on sex work, departing from sex trafficking debates, are heavily engaged in a heteronormative logic that might be unable to approach the complexity and ambiguity of experiences of transgender prostitutes and, therefore, cannot theorize their possibilities of agency. To do so, I will conduct a critique of the naturalization of gender norms that hinders an understanding of experiences that exceed the binary ‘prostitute versus victim.’ I argue how both an abolitionist as well as a legalising solution to the is- sues involved in the sex market, when relying on the state as the guarantor of rights to sex workers, cannot account for the complexities of a context such as the Brazilian one, in which specific concep- tions of citizenship permit violence against sexually and racially marked groups to occur on such a large scale. Keywords: Gender; Prostitution; Sex Trafficking; Queer Theory; Feminism; Travestis. Introduction ‘Prostitution’ as an object of study can be approached through different perspectives that try to pin down exactly what are the social and political problems involved in it, and therefore how it can be dealt with by the State. -

Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum

Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 1 May 2016 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 2 May 2017 V o l u m e 2 M a y 2 0 1 7 Editorial 4-7 Anita Thaler & Birgit Hofstätter Making kin, or: The art of kindness and why there is nothing romantic about it 8-14 Birgit Hofstätter Non-monogamies and queer kinship: personal-political reflections 15-27 Boka En, Michael En, David Griffiths & Mercedes Pölland Thirteen Grandmothers, Queering Kinship and a "Compromised" Source 28-38 Daniela Jauk The Queer Custom of Non-Human Personhood Kirk J Fiereck 39-43 Connecting different life-worlds: Transformation through kinship (Our experience with poverty alleviation ) 44-58 Zoltán Bajmócy in conversation with Boglárka Méreiné Berki, Judit Gébert, György Málovics & Barbara Mihók Queer STS – What we tweeted about … 59-64 2 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 2 May 2017 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum A Journal of the Working Group Queer STS Editors Queer STS Anita Thaler Anita Thaler Birgit Hofstätter Birgit Hofstätter Daniela Zanini-Freitag Reviewer Jenny Schlager Anita Thaler Julian Anslinger Birgit Hofstätter Lisa Scheer Julian Anslinger Magdalena Wicher Magdalena Wicher Susanne Kink Thomas Berger Layout & Design [email protected] Julian Anslinger www.QueerSTS.com ISSN 2517-9225 3 Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum – Volume 1 May 2016 Anita Thaler & Birgit Hofstätter Editorial This second Queer-Feminist Science and Technology Studies Forum is based on inputs, thoughts and discussions rooted in a workshop about "Make Kin Not Babies": Discuss- ing queer-feminist, non-natalist perspectives and pro-kin utopias, and their STS implica- tions” during the STS Conference 2016 in Graz. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

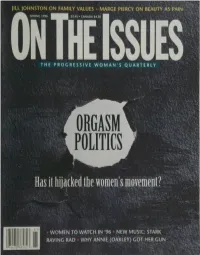

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

The Changing Winds of Civilization: the Aboriginal and Sovereignty Between the Desert and the State,” Intersections 10, No

intersections online Volume 10, Number 2 (Spring 2009) Luke Caldwell, “The Changing Winds of Civilization: The Aboriginal and Sovereignty Between the Desert and the State,” intersections 10, no. 2 (2009): 119-149. ABSTRACT The antagonistic relationship between the Australian state and the Aborigines has deep and problematic roots. Beginning with the racist doctrine of terra nullius, I look at how more than two hundred years of legal policies have consistently constructed the Aborigine as a problem that required a state solution. I argue that these policies are predicated on a complete denial of native sovereignty and have increasingly alienated native communities. By refusing to engage with the source of these problems, the state has created significant barriers to native rehabilitation and has hijacked reconciliation efforts to strengthen its hegemony instead of native groups. Rather than solving the “Aboriginal problem”, these state policies have created it by placing Aborigines in an ambiguous political space that functions as a medium for civilizing the native—a process through which the native is killed and reborn in a form that is unproblematic for the state. http://depts.washington.edu/chid/intersections_Spring_2009/Luke_Caldwell_The_Changing_Winds_of_Civilization.pdf © 2009 intersections, Luke Caldwell. This article may not be reposted, reprinted, or included in any print or online publication, website, or blog, without the expressed written consent of intersections and the author 119 intersections Spring 2009 The Changing Winds of Civilization The Aboriginal and Sovereignty Between the Desert and the State By Luke Caldwell University of Washington, Seattle n 1770, Captain James Cook sailed up the eastern coast of what is now I Australia, unfurled a ―Union Jack‖, and claimed half of an inhabited continent under the authority of the British Crown. -

John Marshall and Indian Land Rights: a Historical Rejoinder to the Claim of “Universal Recognition” of the Doctrine of Discovery

WATSON 1-9-06 FINAL.DOC 1/9/2006 8:36:03 AM John Marshall and Indian Land Rights: A Historical Rejoinder to the Claim of “Universal Recognition” of the Doctrine of Discovery Blake A. Watson∗ I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................481 II. JOHNSON V. MCINTOSH ...................................................................483 III. ROGER WILLIAMS AND “THE SINNE OF THE PATTENTS” .................487 IV. EUROPEAN VIEWS OF INDIAN LAND RIGHTS DURING “THE AGE OF DISCOVERY” ......................................................................498 A. Spanish Views of Indian Land Rights ................................499 B. French Views of Indian Land Rights .................................511 C. Dutch and Swedish Views of Indian Land Rights .............517 D. Early English and Colonial Views of Indian Land Rights ..................................................................................520 V. “THE SINNE OF THE PATTENTS” REDUX: INDIAN TITLE IN NEW JERSEY ............................................................................................540 I. INTRODUCTION John Marshall was a historian as well as a jurist. In 1804, in the introductory volume of his five-volume series entitled The Life of George Washington, Marshall sought to place Washington’s life in con- text by presenting a lengthy narrative “of the principal events preceding our revolutionary war.”1 Almost twenty years later, when crafting the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Johnson v. McIntosh,2 Marshall relied heavily on his history of America “from its discovery to the present day” in order to proclaim “the universal rec- ognition” of two legal principles: (1) that European discovery of lands in America “gave exclusive title to those who made it”; and (2) that ∗ Professor of Law, University of Dayton School of Law. J.D. 1981, Duke Univer- sity School of Law; B.A. 1978, Vanderbilt University. Research for this Article was supported by the University of Dayton School of Law through a summer research grant. -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 97 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition My Vintage Rubble and Fish & Moose series 1 Mini-retrospective by Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wednesday, Feb 1, 6:30 pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 2-6 EXHIBITIONS 7-24 THEATRE 25/26 WORKSHOPS 27-30 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 31 GRANTS 32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 PUBLIC ART 34 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 35 EXHIBITIONS 36-44 FAIR 45/46 FESTIVAL 47-49 JOB CALL 50-56 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 57 PERFORMANCE 58 CONFERENCE 59 PUBLIC ART 60-63 RESIDENCY 64-69 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 70 BY COUNTRY ARGENTINA RESIDENCY 71 AUSTRIA PRIZE 72 BRAZIL RESIDENCY 73/74 CANADA RESIDENCY 75-79 FRANCE RESIDENCY 80/81 GERMANY RESIDENCY 82 ICELAND PERFORMERS 83 INDIA RESIDENCY 84 IRELAND FESTIVAL 85 ITALY FAIR 86 RESIDENCY 87-89 MACEDONIA RESIDENCY 90 MEXICO RESIDENCY 91/92 MOROCCO RESIDENCY 93 NORWAY RESIDENCY 94 PANAMA RESIDENCY 95 SPAIN RESIDENCY 96 RETREAT 97 UK RESIDENCY 98/99 USA COMPETITION 100 EXHIBITION 101 FELLOWSHIP 102 RESIDENCY 103-07 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 108 SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 109 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 110 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 111 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: February 1 - 24 My Vintage Rubble, Fish and Moose series – Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wed. -

Marc Simmons; Historian of the Southwest

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 80 Number 3 Article 11 7-1-2005 Review Essay: Marc Simmons; Historian of the Southwest Richard W. Etulain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Etulain, Richard W.. "Review Essay: Marc Simmons; Historian of the Southwest." New Mexico Historical Review 80, 3 (2005). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol80/iss3/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Review Essay MARC SIMMONS: MAVERICK HISTORIAN OF THE SOUTHWEST Richard W. Etulain arc Simmons, New Mexico's leading historian, has always ridden a Mhorse ofanother kind. Freed from aCCiclemic turfsquabbles, working primarily outside the classroom, and writing most often for newspaper and other lay historians, Simmons remains his own historian. Launched as a doctoral graduate in the mid-196os from the University of New Mexico (UNM), Simmons's subsequent historiographical journey, although indi vidualistic, followed more closely the paths ofFrance V. Scholes and Herbert Eugene Bolton than the newer revisionist writings of scholars like Ramon Gutierrez. But to be more precise, Simmons is sui generis, a historian ofhis " own stripe, different from most other historians of New Mexico and the Southwest. The volume under review, librarian Phyllis Morgan's exceptionally use ful bio-bibliography, thoroughly displays the extraordinary dimensions of Marc Simmons ofNew Mexico: Maverick Historian. By Phyllis Morgan. -

Settlement of the West

Settlement of the West The Western Career of Wild Bill Hickok James Butler Hickok was born in Troy Grove, Illinois on 27 May 1837, the fourth of six children born to William and Polly Butler Hickok. Like his father, Wild Bill was a supporter of abolition. He often helped his father in the risky business of running their "station" on the Underground Railroad. He learned his shooting skills protecting the farm with his father from slave catchers. Hickok was a good shot from a very young age, especially an outstanding marksman with a pistol. He went west in 1857, first trying his hand at farming in Kansas. The next year he was elected constable. In 1859, he got a job with the Pony Express Company. Later that year he was badly mauled by a bear. On 12 July 1861, still convalescing from his injuries at an express station in Nebraska, he got into a disagreement with Dave McCanles over business and a shared woman, Sarah Shull. McCanles "called out" Wild Bill from the Station House. Wild Bill emerged onto the street, immediately drew one of his .36 caliber revolvers, and at a 75 yard distance, fired a single shot into McCanlesʼ chest, killing him instantly. Hickok was tried for the killing but judged to have acted in self-defense. The McCanles incident propelled Hickock to fame as a gunslinger. By the time he was a scout for the Union Army during the Civil War, his reputation with a gun was already well known. Sometime during his Army days, he backed down a lynch mob, and a woman shouted, "Good for you, Wild Bill!" It was a name which has stuck for all eternity.